Laboratorium voor - Lirias

advertisement

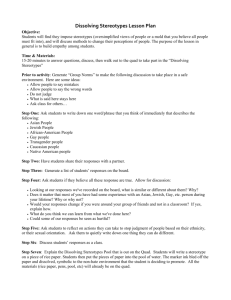

Laboratorium voor Experimentele Sociale Psychologie K.U.Leuven Departement Psychologie Guido Peeters Self-Other anchored evaluations Of national stereotypes Internal Report No 5 May 1993 Mailing address: Guido Peeters LESP Tiensestraat 102 B-3000 LEUVEN, Belgium e-mail: guido.peeters@psy.kuleuven.be 1 Self-Other Anchored Evaluations of National Stereotypes Abstract National stereotypes drawn from the literature were plotted against two evaluative dimensions connected (in previous studies) with social value orientations and referred to as: SP (Self Profitability or good/bad for the self) and OP (Other Profitability or good/bad for the other). In study 1, 108 stereotypes were plotted using a standardized procedure involving translation of stereotype trait terms into the native language of judges who rated the terms for SP and OP. Study 2 was a reinterpretation and statistical reanalysis of data published in a study on national characteristics (Peabody, 1985). Convergent results from both studies suggest that positive and negative stereotypes are not simply contrasted as opposite poles of a general good/bad dimension. Specifically, positive stereotypes tended to be marked by SP (associated with an individualistic value orientation) and the negative ones rather by OP (associated with aggression). Further, SP valences of stereotypes were more stable than OP valences which fluctuated as a function of changing international relationships. Finally, the SP dimension differentiated between enemy stereotypes contrasting "respected" versus "despised" enemy images. -------------------------Note. This paper was prepared in 1992 and presented at the Annual Meeting of the Belgian Psychological Society, Ghent, May 28, 1993. Thanks are due to Suzanne Gabriels for her able assistance in study 1. 2 Self-Other Anchored Evaluations of National Stereotypes In general stereotypes have pronounced evaluative meanings or good-bad connotations which are considered to have high psychological significance. However it is not clear how this psychological significance is to be conceived of. The reason may reside in the lack of an appropriate theory of evaluative meaning. For instance, trait dimensions obtained by factor analysis are often defined as "evaluative" on the mere basis of an intuitive appreciation of the good-bad character of some representative traits. Hence in the present paper evaluative meanings of national stereotypes are analysed in the light of a more elaborate theory referred to as the relativistic evaluative-meaning concept (Peeters, 1979, 1982, 1986) and some psychological implications will be explored. The Relativistic Evaluative-Meaning Concept. The evaluative categorization of an object as "good" or "bad" is called "relative" because related to (a) descriptive attributes of the object on the one side and (b) evaluative norms or standards held by the evaluating subjects on the other hand. It follows that evaluative meanings accorded to the attributes may vary over evaluated objects as well as over evaluating subjects. For instance, "cold" may be positive when attributed to beer, but negative when attributed to coffee, at least as far as current evaluative standards concerning beer and coffee imply that the former should be cold while the latter should be hot. However, some subjects may hold different evaluative standards and for instance, like their coffee cold. Hence, the evaluative meaning of a descriptive term such as "warm" depends on both the term's referent and the evaluative standard held by the evaluating subject. At a first glance one might conclude from this theory that evaluative meanings should be very unstable because varying over context. Elsewhere (Peeters, 1979) the theory is shown to account for certain instabilities observed in studies on evaluative meaning, indeed, but it points to stabilities as well. For instance, it defines a class of terms that convey directly the agreement or disagreement of the referent with an evaluative standard without explicit reference to descriptive attributes. Similar direct evaluative meanings are carried by terms such as good, bad, favourable, unfavourable, etc. and they are very stable. Indeed, "good" means "good" except if two incompatible evaluative standards are applied as it was noticed yet by Rommetviet (1968) observing that "good" weather for swimming may be "bad" weather for fishing. However, high constancy is not limited to the "direct" type of evaluative meaning but can be observed for the "indirect" type as well, specifically in cases where evaluative standards are stable in time and across evaluating subjects. Hence the question arises whether some very widespread, perhaps universal, evaluative standards could be designated. Adages such as "Everyone to his taste" seem to deny it. Fortunately evaluative standards are not based on taste only. More constant evaluative standards may reflect the adaptive value of perceived objects and their attributes. In this way the positive evaluation of "edible" as an attribute of "food" may be universal. It was further demonstrated that when the object of the evaluation is a person, the adaptive value of an attribute of the person can be defined from two perspectives: that of the self and that of the other. Both perspectives were associated with universal evaluative standards involving universal evaluative categories or "dimensions" referred to as self-profitability or "SP"and other- profitability or "OP". Self-profitability (SP) refers to the perceived adaptive consequences of an attribute for the self which means: for the individual who has the attributes. Other-profitability (OP) refers to 3 the perceived adaptive consequences of the attribute for the other person who has to deal with the individual who has the attribute. As perceived consequences can be either positive (enhancing good adaptation) or negative (detracting from good adaptation), SP and OP constitute two bipolar evaluative dimensions: (a) +SP or "good for self" against -SP or "bad for self" and (b) +OP or "good for other" against -OP or "bad for other". self-profitable (+SP) attributes are associated with positive consequences, while negative (-SP) ones with negative consequences. For instance, high cleverness may be categorized as +SP in that it seems unconditionally good for the clever person him- or her-self while it seems ambiguous for the the other. Cleverness that belongs to a friend may be +OP but belonging to an enemy it would be -OP. Generosity, however, may be categorized as +OP in that it seems unconditionally good for the other while ambiguous for the self. Indeed, generosity may be +SP if it is reciprocated, but -SP if it is exploited by the other. The measurement of SP and OP. As this issue has been extensively dealt with in another paper (Peeters, in press) we shall confine ourselves to some points concerning two methods used for assessing SP and OP values of traits and referred to as "Claeys method" and "Peeters method". The Claeys method simply measures the SP and OP values of a trait by asking judges to rate how (dis)advantageous the trait is, respectively for the person who has that trait (SP) and for the other with whom that person is in contact (OP). This method is very reliable, Cronbach alpha for the agreement between nine judges amounting to .96 for both the SPand the OP-ratings of 280 traits (De Boeck & Claeys, 1988, cit. in Peeters, in press). Further, the method seems valid for measuring OP but not SP of traits with relatively extreme OP values. Apparently high OP seems to involve secondary or conditional SP that is confounded with the primary unconditional SP we are interested in. Thus the SP ratings of traits are only valid if the traits are rated neutral for OP. The Peeters method requires subjects to match traits with given sets of "key-traits" each set being representative of one pole of one dimension, either SP or OP. It is evident that similar sets of key-traits can be selected using the Claeys method. For instance if a trait is rated neither advantageous nor disadvantageous for the "other" but very advantageous (versus disadvantageous) for the "self", then it may make an excellent +SP (versus -SP) key-trait. SP and OP values of target traits have been measured using rating scales marked by sets of key-traits completed with specifications about the traits' advantageousness for either "self" or "other". For instance, the SP rating scale is presented in fig. 1. Judges were asked to rate to which extent the target trait belonged to either the left or the right set. Notice that the key-traits are translated from Dutch and may not be suited for other language-culture communities where appropriate key-traits can be defined using the Claeys method as described higher. OP-values were obtained by a similar scale contrasting an -OP set (intolerant, selfish, impassive, untrustworthy, suspicious--traits disadvantageous for the socius in the first place) against a +OP set (tolerant, generous, sensitive, trustworthy,trusting--traits advantageous for the socius in the first place). Correlations between small groups of judges who rated the same lists of traits have been found to range from .67 to .86 for SP and from .87 to .95 for OP (Peeters, in press). This means that also the Peeters method is quite reliable, but more for measures of OP than of SP. 4 WEAK POWERFUL AMBITIONLESS AMBITIOUS SHY SELF-CONFIDENT CLUMSY PRACTICAL SLOW QUICK (Traits that are disadvan(Traits that are advantatageous for the own self geous for the own self in in the first place) the first place) :_____________________________________________: -4 -3 -2 -1 0 +1 +2 +3 +4 Fig. 1. The SP rating scale. Psychological significance of SP and OP. Although SP and OP may not by far exhaust the possible range of evaluative meaning categories, they may have high theoretical and practical relevance. First of all, being self-other anchored categories they may be prominent because strong self-other anchoring biases have been observed in social cognition (Peeters, 1983, 1987, 1991). Further SP and OP have been related to a variety of well-established concepts in different areas of psychological research including Osgood's semantic differential (Peeters, 1986 and in press), implicit personality theory (Peeters, 1983), and social motivation or "value orientations" (Peeters, 1983). Finally, OP has been related to the approach- avoidance dichotomy +OP others being approachable, -OP others to be avoided (Peeters & Czapinski, 1990). Table 1. SP and OP associated with social value orientations (N = Number of corresponding stereotypes) ---------------------------------------------------------------------SP -------------------------------------------------------------0 + --------------------------------------------------------------------- OP + MARTYRDOM (MART) (N=0) ALTRUISM (ALT) (N=1) COOPERATION (COOP) (N=4) 0 MASOCHISM (MAS) (N=1) (N=65) INDIVIDUALISM (IND) (N=22) - SADOMASOCHISM (SADOM) AGGRESSION (AGG) COMPETITION (COMP) (N=2) (N=13) (N=0) ---------------------------------------------------------------------For the further elaboration of those issues the reader is referred to the studies mentioned. Only the connection of SP and OP with the model of "social value orientations" of the Santa Barbara school (McClintock and colleagues, e.g.: McClintock, 1988) is slightly elaborated in table 1 because the terminology of the Santa Barbara model will be used to designate various combinations of SP and OP. Study 1: SP and OP of National Stereotypes Method. 108 National stereotypes were drawn from 14 sources briefly described in table 2 and henceforth referred to by their code letters A,B,.. N. Each stereotype consisted of a list of attributes (lazy, very 5 religious, etc.). English and German attribute terms were translated into Dutch and the translations were checked by back-translations into the original language. Table 2. List of sources with code letter (A, B,..N) ---------------------------------------------------------------------A: Child and Doob (1943): Americans describing eight nationalities in 1938 and 1940. B: Everts and Tromp (1980): compilation of stereotypes concerning Russians in six West-European countries about 1948. C: Frank (1982): Americans describing Germans, Japanese, Russians and Chinese in 1942 and 1966 D: Karlins, Coffman, and Walters (1969): compilation of American stereotypes concerning eight nationalities in 1933, 1951 and 1967. E: Kippax and Brigden (1977): Australians describing 12 nationalities in 1974. F: Meenes (1943): Black Americans describing 8 nationalities in 1935 and 1942. G: Nuttin (1976): Reciprocal stereotypes of Flemings and Walloons (Belgium, around 1971) H: Prothro (1954): Armenians (students in Lebanon) describing 11 nationalities. I: Prothro and Melikian (1955): Arabians describing Americans, Germans, Englishmen and Japanese in 1952. J: Saenger and Flowermans (1954): Americans describing Americans and Italians. K: Schneider (1979): compilation of German stereotypes concerning Poles around World War II, 1963 and 1972. L: Wecke, Schmetz, and De la Haye (1980): Dutch stereotypes of Russians before (1979) and after (1980) the intervention in Afghanistan. M: Wecke, Schmetz, and De la Haye (1981): Dutch stereotypes concerning leaders and populations of Arabian oil countries (about 1979). ---------------------------------------------------------------------Then each attribute (N=222) was rated for SP and OP following the Peeters method described higher. Judges were 27 Dutch-speaking Flemish students from various faculties and 13 community people. They were divided in two equivalent groups: one for the SP- and another for the OP- ratings. Each group was divided further into four subgroups of five judges varying as a function of gender and order of presentation of the attributes. Product moment correlations between ratings of different subgroups computed over attributes ranged from .89 to .92 for OP, while from .67 to .82 for SP. Apparently the measures of SP and OP were quite reliable, but less reliable for SP than for OP. An examination of standard deviations of SP and OP ratings showed that the difference in reliability was due to a lower agreement among SP judges rather than to a lower variability of the SP ratings. Indeed, variability of among judges was higher for ratings of SP (SD>2 for 33% of the attributes) than of OP (SD>2 for only 1% of the attributes). SP and OP values were assigned to individual attributes by averaging the corresponding ratings over the 20 judges. Subsequently the SP and an OP values were determined for each stereotype by computing weighted averages of SP and OP values of the attributes that constituted the stereotype. The weights were proportional to the number of respondents that, in the original study, had assigned the attribute to the stereotyped target. The procedure is illustrated by the following simplified example. Imagine that X-landers describe Y-landers using only two attributes: cruel (OP-value = -3.40) and industrious (OP-value = +1.30); the term "cruel" is used by 80% of the X-lander judges, while "industrious" by only 40% of them. The OP-value of the X-lander stereotype about Y-landers then is computed as follows: 6 OP = [80.(-3.40) + 40.(1.30)].[1/(80 + 40)] = -1.83 Thus SP and OP values were conceived as means over N observations whereby N was a sum of percentages rather than a raw frequency. Also the corresponding standard deviations were computed as a raw index of the stereotype's internal consistency. By this procedure data only available as percentages could be used. The fact that N did not reflect the number of degrees of freedom did not matter because conclusions were drawn only from very salient patterns the analysis of which did not involve significance testing. Results and Discussion. In the following paragraphs stereotypes are referred to by the name of the stereotyping agent or group, followed by the stereotyped group, and further by the year (approximately) in which the stereotype was measured followed by the code of the source (table 2). Thus "Americans about Japanese (1942C)" means: "the American stereotype of the Japanese about 1942 drawn from source C". Because of the rather rough method, involving translation and estimations by judges, it may not be recommended to focus on single stereotypes but rather to look for general patterns (SP and OP values of separate stereotypes are added in appendix). For the same reason, extreme outcomes may deserve more attention that rather neutral ones. Hence it was decided to categorize stereotypes as manifest SP or OP if they deviated at least by one SD of the neutral middle of the given scale. In this way the stereotypes could be associated with the eight social motives. As shown in table 1, 65 stereotypes deviated by less than one SD on both dimensions and are further disregarded. Only six out of the remaining 43 stereotypes deviated by 1 SD or more on both dimensions: four ones combining +OP with +SP (associated with the value orientation COOPERATION), while two ones combining -OP with +SP (SADOMASOCHISM). More surprising may be the distribution of the 37 stereotypes that met the extremity criterion of one SD for only one dimension. Stereotypes that could be associated with ALTRUISM (+OP) and MASOCHISM (-SP) seemed almost absent, while those associated with INDIVIDUALISM (+SP) and AGGRESSION (-OP) seemed dominant. Hence for a closer examination of the data we shall proceed from the latter dominant categories. The friendly stereotype: from individualism to altruism. The 22 manifest +SP stereotypes were split up in "rather cooperative" and "rather competitive" cases according as their OP scores were either positive or negative, although deviating by less than one SD from zero. 17 Of them were on the "cooperative" (+OP) side. They included four American autostereotypes (1933D, 1938A, 1951D, 1954J), and further black Americans about white Americans (1942F); Americans about English (1938A), about Germans (1933D, 1935F, 1967D), and about Japanese (1933D, 1935F, 1967D); Arabs about Americans (1952I) and about Germans (1952H); Australians about Chinese (1974E) and about Russians (1974E); Armenians about Russians (1952H). On the "competitive" (-OP) side only three stereotypes were observed: Black Americans about white Americans (1935F) Australians about Americans (1974E), and Armenians about Germans (1952H). Apparently pronounced +SP stereotypes have more cooperative than competitive connotations and they seem to involve predominantly friendly nations. The +SP character of friendly stereotypes is further confirmed by two pure +SP stereotypes (with zero OP value) including an American autostereotype (1967D) and one of Americans about Germans (1951D). In addition, four out of the five stereotypes with a +OP score of at least one SD above zero, are of the "cooperative" type with also +SP at least one SD above zero. They include a German autostereotype 7 (1948N) and further stereotypes of Americans about Japanese (1966C), Armenians about Americans (1950H) and Australians about Japanese (1974E). Even the only "altruistic" stereotype (Americans about Italians, 1951D) is slightly biased towards +SP (SP=.60, SD=.76). The relatively low prevalence of +OP as compared to +SP in friendly stereotypes may surprise but could be due to the composition of the sample. Anyway, it suggests that +SP is to be considered as a genuine evaluative category relative to positive stereotypes. Negative stereotypes: from competition to sadomasochism. Examining the distribution of "aggressive" (-OP) stereotypes along the SP dimension, we could distinguish between a rather +SP "competitive" and a -SP "sadomasochistic" group. First, the competitive group included stereotypes expressed during the oil crisis by Australians about Arabs (1975E), and by Dutchmen about political leaders of oil countries (1979M). Further they included American stereotypes about Germans (1942C) and Japanese (1942C) during the second world war, and about Chinese (1966C) and Russians (1966C) during the cold war. Finally there were four Dutch cold-war stereotypes about Russians (1979L and 1980L) of which one was neutral for SP and thus on the border between competition and sadomasochism. Second, the sadomasochistic group included only four of the 13 "aggressive" stereotypes reported in table 1.: Americans (1951D) and Armenians (1952D) about Turks; West Germans about Russians (1948N); West Germans about Poles (1963K). However we can add the two "sadomasochistic" (-OP/-SP) stereotypes (Americans about Turks, 1933D, and the Hitlerian doctrine about Poles, 1940K), and the only "masochistic" (-SP) case which was also rather on the "sadomasochistic" side (Germans about Poles 1963K). Although there are some exceptions such as the negative view of Americans on Turks which is perhaps due to lack of familiarity, both groups concern predominantly antagonist nations. A comparison of the competitive and sadomasochistic groups suggests the following hypothesis about the psychological meaning of enemy stereotypes. There are two enemy stereotypes which could be regarded as the extremes of a continuum. Both have negative OP valences but contrasting SP valences. Firstly, +SP characterizes the respected enemy stereotype illustrated by the "competitive" group. The respected enemy is usually not a neighbour. The hostility is temporary and related to a conflict of interests that can be very intense, but allows for an optimistic long-term prognosis. This is illustrated by the American stereotypes of Germans and Japanese. During the war the pre-war +SP evaluation tended to persist. Only OP turned radically into the negative but switched back to the pre-war position once the war was overe. Secondly, -SP characterizes the despised enemy stereotype illustrated by the "sadomasochistic" group. Despised enemies are often neighbours with an age-long history of antagonism that does not allow for a favourable prognosis. Moreover, the contrast with the +SP images of the own and friendly nations suggests that the hostility reflects more than just to the animosity associated with a conflict of interests but involves also a good deal of ethnocentrism. Stability of SP and OP. The concept of respected enemy implies high constancy of SP but not of OP. This was tested by comparing profiles of OP and SP over five national stereotypes obtained from American judges at five points of time. The stereotypes concerned Americans, English, Germans, Italians and Japanese. The points in time (with letters referring to the sources in table 2) were: 1933D, 1938A, 1940A, 1951D, and 1967D; they allowed for 10 pairwise comparisons made by computing product moment correlations (r) over the five nationalities. For OP r ranged from -60 to .65, the mean (computed using Fisher's Z transformation) amounting only to .11. This low r seems in agreement 8 with the hypothesized instability of OP over time, Alternatively it might be explained as just reflecting low reliability of our measurement method. However, this alternative explanation is disconfirmed by surprisingly high r's for SP ranging from .18 to .98 (mean: .71) which were obtained in spite of the lower reliability of SP measures than of OP-measures mentioned higher. These high r's do not only argue for the hypothesized stability of SP over time, but also for the reliability of our measurement method. Apparently SP values of stereotypes are quite stable over time while OP values fluctuate as a function of varying circumstances such as changing international relations. Study 2: SP and OP in Peabody's Data on National Characteristics One of the unanticipated outcomes of the present study was the high preponderance of +SP, as compared to +OP, in friendly stereotypes. As this preponderance might be due to the composition of our sample, additional evidence was looked for in a notorious study on national characteristics by Peabody (1985) in which data are presented on 75 stereotypes of predominantly European nations obtained from predominantly European subjects. In order to isolate the descriptive from the evaluative components of stereotypes, Peabody measured national stereotypes using sets of two bipolar trait scales (a and b) in which opposite evaluations were associated with the same descriptive contents. For instance: a. Thrifty (+) / Extravagant (-) b. Stingy (-) / Generous (+) Using factor analysis, Peabody derived two main descriptive dimensions: tight vs. loose and assertive vs. unassertive. Each dimension constituted a descriptive continuum with negatively valued extremes. For instance, the four abovementioned traits belonged to the tight-loose continuum ranging from too tight (b. stingy -) over optimally tight (a. thrifty +) and optimally loose (b. generous +) to too loose (a. extravagant -). Peabody (o.c.,pp.28-30) reported seven sets of two scales to be representative for the tight/loose dimension. The a-scales in these sets were: "thrifty/extravagant, self-controlled/impulsive, serious/frivolous, skeptical/gullible, firm/lax, persistent/vacillating and selective/undiscriminating. The b-scales were: stingy/generous, inhibited/spontaneous, grim/gay, distrustful/trusting, severe/lenient, inflexible/flexible, choosy/broad-minded. When we compare these scales with representative SP and OP traits, such as those presented higher in the section on the measurement of SP and OP, then we might tentatively conclude that the a-scales tend to contrast +SP against -SP, while the b-scales -OP against +OP. Thus, a reasonable working assumption may be that a mean a-scale score can be used as an index of SP, while a mean b-scale score as an index of OP. Specifically within the tight-loose dimension "too tight" and "optimally loose" are associated respectively with -OP and +OP, while "too loose" and "optimally tight" respectively with -SP and +SP. In an analogous way, SP and OP can be related to the two sets of two scales that Peabody found to be representative for the dimension assertive-unassertive. This time, the a-scales represent +/- OP (peaceful/aggressive, modest/conceited) and the b-scales -/+ SP (passive/forceful, unassured/self-confident). Thus within the assertivity dimension, "too assertive" and "optimally unassertive" are associated with -/+ OP, while "too unassertive" and "optimally assertive" with -/+ SP. The various relationships between Peabody's descriptive dimensions and the SP/OP model (with the corresponding social orientations) are summarized in table 3. 9 As Peabody (1985, tables 7.2, 8.2,.. .16.2) reported detailed outcomes for separate scales it was easy to estimate SP and OP values of the stereotypes by computing averages for the abovementioned a-scales and b-scales separately. In that 7-point scales were used, these values could range from -3 to +3. Peobody (o.c., p. 53) considered differences of at least 0.5 as "notable". Hence, I decided to accord zero values to average values between -0.5 and +0.5. In this way the 75 stereotypes could be plotted against SP and OP in the same way as in study 1. Table 3. Study 3: SP and OP associated with Peabody's tight/loose and and assertive/unassertive dimensions. The labels between brackets refer to the value orientations in table 1. 'Opt.' means 'Optimally'. N=number of corresponding stereotypes drawn from Peabody (1985). ---------------------------------------------------------------------OP SP (Tab. 1) Tight/loose Assertive/unassertive ---------------------------------------------------------------------+ - (MART) Opt. loose + Too loose Opt. unass. + Too unass. (N=9) (N=3) + 0 (ALT) Opt. loose Opt. unass. (N=9) (N=3) + + (COOP) Opt. loose + Opt. tight Opt. unass. + Opt. ass. (N=6) (N=18) 0 + (IND) Opt. tight Opt. ass. (N=21) (N=19) - + (COMP) Opt tight + Too tight Opt. ass. + Too ass. (N=15) (N=20) - 0 (AGG) Too tight Too ass. (N=0) (N=3) - - (SADOM) Too tight + Too loose Too ass. + too unass. (N=0) (N=2) 0 - (MAS) Too loose Too unass. (N=4) (N=1) ---------------------------------------------------------------------Results SP and OP values of the stereotypes were computed separately for the descriptive dimensions "tight-loose" and "assertive-unassertive". The number of neutral stereotypes (scoring zero for both SP and OP) amounted only to 11 out of 75 in the tight-loose analysis and to 6 in the assertive-unassertive analysis. This is proportionally much less than the 65 neutral cases in study 1 where, because of the presumed low reliability of the measuring procedure, a rather conservative cutoff point was used. As shown in table 3, and in agreement with study 1, there was a preponderance of +SP over +OP cases for each dimension separately. However, those data are somewhat ambiguous relative to the global SP and OP values of the stereotypes. For instance, stereotypes rated +SP for one dimension may be rated -SP for the other. For that reason each stereotype was plotted against the eight value orientations represented in table 1 for both dimensions. The resulting classification is presented in table 4. When both dimensions converged to the same value category, then, of course, the label of that category was used (e.g.: COOPERATION). If the dimensions diverged, and the stereotype was classified into two value categories separated in table 1 by only one intermediate category, then the label used consisted of the intermediate category followed by the two original categories (abbreviated and between brackets). For instance, a stereotype categorized as ALTRUISTIC on the one dimension and INDIVIDUALISTIC on 10 the other was labelled: "COOPERATION (ALT+IND). Stereotypes involving just two adjacent categories were labelled by those categories (e.g.: COOPERATION+INDIVIDUALISM). Table 4. Study 2: Social orientations associated with various stereotypes on the basis of the latter's SP and OP values standing out on either the dimension tight/loose (T) or the dimension assertive/ unassertive (A) or both dimensions (no mark). --------------------------------------------------------------------MARTYRDOM -- N=5: South Italians about South Italians (T); Italians about French (T); Greek about Italians (T); Italians about Italians (T); Germans about Austrians (A) ALTRUISM -- N=1: Austrians about Austrians (A) MARTYRDOM+ALTRUISM -- N=1: Filipinos about Filipinos COOPERATION -- N=6: Germans about Finns; English about Dutch; Germans about Dutch; French about Dutch; Chinese about Chinese; Chinese+Filipinos about Americans COOPERATION (ALT+IND) -- N=5: English about French; French about Americans; Germans about Swiss; English about English; Greek about Greek COOPERATION+INDIVIDUALISM -- N=7: Germans about English; French about English; Finns about English; French about Swiss; Italians about Swiss; Austrians about Swiss; Greek about North Greek INDIVIDUALISM -- N=14: Austrians about English; French about Germans; Finns about West Germans; Greek about Americans; Finns about Swedish Finns; Finns about Russians; North Italians about North Italians; Germans about Germans (T); Germans about Americans (A); English about Americans (A); English about Irish (A); Greek about French (A); Finns about Swedes (A); Austrians about Hungarians (A) INDIVIDUALISM (COOP+COMP) -- N=5: Finns about Finns; Filipinos about Chinese; Greek about English; Germans about Russians; Austrians about Russians INDIVIDUALISM+COMPETITION -- N=7: Austrians about Germans; English about Germans; Italians about English; Finns about East Germans; French about Russians; Italians about Russians; Greek about Russians COMPETITION -- N=5: Greek about Germans; Italians about Austrians; South Italians about North Italians; English about Russians; French about French (A) COMPETITION+AGGRESSION -- N=1: Italians about Germans AGGRESSION -- N=1: North Italians about South Italians (A) SADOMASOCHISM (AGG+MAS) -- N=1: French about Spanish SADOMASOCHISM+MASOCHISM -- N=1: Greek about Turks MASOCHISM -- N=1: Chinese about Filipinos --------------------------------------------------------------------13 Stereotypes involved categories separated by more than one intermediate category (e.g.: MARTYRDOM combined with INDIVIDUALISM). 11 They were discarded from the evaluative analysis because they implied opposite valences of either SP or OP or both. For instance, they included three stereotypes about the French combining +OP of ALTRUISM within the tight/loose dimension with -OP of COMPETITION within the assertive/unassertive dimension. There were even two stereotypes about Italians in which the contrast involved both SP and OP in that MARTYRDOM in the tight/loose dimension was combined with COMPETITION in the assertive/unassertive dimension. Similar discrepancies may be interesting because they imply that two stereotypes may be available to the judges depending on which descriptive dimension is made salient. For instance, people who intend to visit France as tourists may focus on the first dimension stressing the optimally loose "altruistic" character of the French, while in case of conflict they may focus on the second dimension stressing the harsh assertive character of the "competitive" French. However, the systematic exploration of similar dualities would reach beyond the scope of this paper. For some stereotypes, the association with a value category was limited to one dimension while on the other dimension it was categorized as neutral. These stereotypes were not discarded but in table 4 they are marked either "T" or "A" (added between brackets) indicating whether the classification is based either on the tight/loose (T) or assertive/unassertive (A) dimension. Only one stereotype was to be discarded because it scored neutral on both dimensions. By this procedure, the original eight value categories of table l were transformed in a series of 24 categories. In table 4 they are presented in an order corresponding to a clockwise course through table 1, beginning with MARTYRDOM. Only categories that applied to at least one stereotype are presented. Discussion A main aim of study 2 was to check whether the dominance of +SP over +OP, and of -OP over -SP could be replicated. The results in table 4 show that there are 50 stereotypes having at least some +SP (i.e. cases with category labels including at least one of the terms "COOPERATION, INDIVIDUALISM, and COMPETITION" or their abbreviations. However, the number of stereotypes with at least some +OP (category labels including at least one of the terms "MARTYRDOM, ALTRUISM, COOPERATION" or their abbreviations) amount only to 30. Thus the predominance of +SP over +OP in stereotypes is confirmed. However, as was observed yet for study 1, this result may just be due to the composition of the sample. More important is the fact that also study 2 confirms that most of the "individualistic" stereotypes characterized by +SP without +OP concern friendly nations, including in some cases (French, Germans, North Italians) the own nation. Turning to the negative valences, there are 21 stereotypes having at least some -OP (marked by labels including at least one or more of the terms COMPETITION, AGGRESSION, SADOMASOCHISM and their abbreviations). However, the cases with -SP (marked by SADOMASOCHISM, MASOCHISM, MARTYRDOM or their abbreviations) amount only to nine. In agreement with study 1, OP seems to stand out in the negative valences while SP in the positive valences. Another aim of study 2 was to look for further evidence that might substantiate the distinction between the respected and despised enemy images. As Peabody's data were gathered during the cold war period, we looked in the first place for Western stereotypes about Russians. In study 1 they ranged from "individualistic with a cooperative connotation" to "aggressive with a sadomasochistic connotation" the central tendency being "aggressive with a competitive connotation". In the present study (table 4), they ranged from INDIVIDUALISM and 12 INDIVIDUALISM (COOP+COMP), over INDIVIDUALISM+COMPETITION to COMPETITION, the central tendency being in the area of "individualism with a competitive connotation". Thus in both studies, Western stereotypes about Russians are predominantly +SP and tend to be competitively oriented as is the respected enemy image. At the same time it is evident from table 4 that competitively described targets are not necessarily enemies. As indicated in table 3, +SP is associated with tightness and assertivity which according to Peabody (o.c.) may reflect objective national characteristics that form the kernel of truth underlying national stereotypes. The subjective aspect of the stereotype then would reside in the subjective evaluation accorded to those objective characteristics. If tightness and assertivity are positively viewed, they correspond to the "individualistic" +SP image which we found so often in the friendly stereotypes. If the same traits are negatively viewed, ("too tight" and "too assertive") then the corresponding image moves over the "competitive" to the "aggressive" -OP class of stereotypes. Hence the competitive image of the Greek about the Germans (table 4) may not be a remnant of the second world war but could just mean that the tightness and assertivity displayed by the German national character exceeds somewhat the degree Greeks consider as optimal. It is noteworthy that Peabody points out that the stereotypes he obtained about the Russians are inconsistent with the Russian national character. This might argue for the interpretation of those stereotypes as the expression of subjective attitudes towards a target viewed as a "respected enemy". Peabody's hunch that those attitudes may be objectively grounded on the policy of the Soviet Union does not detract from this interpretation because it may always be possible to point selectively to some presumed objective basis for whichever attitude. As to the despised enemy image, which should connote "sadomasochism", there are only two candidates: the stereotype of French about Spanish, and that of Greek about Turks. The case of the Spanish may surprise, as did the Americans' stereotype about Turcs in study 1. In table 4 is shown that the "sadomasochistic" connotation of the stereotype resides in a combination of AGGRESSION on the assertive/unassertive dimension and MASOCHISM on the tight/loose dimension. This allows for the possibility that, instead of "despised enemies", the Spanish are just too loose and too assertive according to the French taste. A similar interpretation, however, cannot be applied to the Greek stereotype about Turks. It implies a MASOCHISM component that could be interpreted as "too loose according to the Greek taste", indeed, but it implies also a SADOMASOCHISM component according to which they would be both "too assertive" and "too unassertive". This inconsistency within a descriptive dimension argues for an evaluative interpretation such as in terms of a "despised enemy" image which is, moreover, confirmed by the well-known age-long history of antagonism between Greek and Turks. Conclusion One way to gain insight in the psychological significance of stereotypes may be by relating them to other psychological concepts. In this perspective two studies were reported in which national stereotypes were plotted against two evaluative dimensions, SP and OP, of which the psychological significance was demonstrated previously. Each study implied at least one salient source of potential error being the handling of original English and German material in Dutch translation in study 1, and the matching of SP and OP with certain subscales of Peabody's tight/loose and assertive/unassertive dimensions in study 2. Nevertheless, the outcomes were remarkably convergent. This argues of course for their validity, but further validation could 13 still be pursued, for instance by replicating study 1 in different countries with judges using different languages. Meanwhile the general pattern displayed by the present data is very suggestive and provides some elements for a theory which can be summarized as follows. The evaluative component of stereotypes involves the dimensions SP (good/bad for the self) and OP (good/bad for the other). Within the SP dimension, the positive pole seems more prominent than the negative one, while within the OP dimension the negative pole seems more prominent. This means that in presumed friendly stereotypes, properties such as power, ambition, self-confidence etc. stand out more than do generosity, tolerance, honesty, etc., while in presumed enemy stereotypes it is the lack of generosity, tolerance, honesty, etc. that stands out more than the lack of power, ambition, self-confidence etc. The SP valence of stereotypes seems more stable than the OP valence. In this way the +SP assigned to a friendly nation may change little when, in an international conflict, the "friend" turns into an "enemy". However the assigned OP may shift dramatically from neutral or positive to negative resulting in a respected enemy image which lasts until the end of the conflict whereafter OP moves back to a neutral or positive position. The respected enemy image can be contrasted with a despised enemy image (-OP combined with -SP). It is associated with ethnocentrism accompanying a long lasting antagonism rather than a temporary conflict. Given the high stability of the SP dimension, an enemy image may not readily turn from despised into respected or vice versa. Hence the despised enemy may only turn into a friend by moving up along the OP dimension which may result in the evaluative combination of -SP and +OP higher categorized under the label "martyrdom". However, the occurrence of this category seems exceptional, at least among national stereotypes. Indeed, no cases were observed in study 1 while the five cases in study 2 are ambiguous because limited to only one descriptive dimension. One condition in which dramatic shifts within the SP dimension may occur after all is when a stereotype is +SP in one descriptive dimension, while -SP in another. A case in point was the combination of MARTYRDOM (-SP) and COMPETITION (+SP) observed in certain stereotypes depicting Italians as too loose (-SP) and too assertive (+SP). It seems evident that in such cases SP may vary as a function of "dimensional salience", a phenomenon that has been extensively studied in the Tajfel tradition of social psychological research (e.g.: Van der Pligt & Eiser, 1984). Finally, the association of certain evaluative configurations with enemy images does not necessarily mean that the presence of those configurations in stereotypes reveals a hostile attitude. It may only make sense to interpret stereotypes as enemy images if one knows already from other sources that there is an antagonistic relationship. When in the public opinions of conflicting nations the respected enemy image prevails, then peacemakers may be more optimistic about restoring peace than when the despised enemy image prevails. 14 References Child, I. L., & Doob, L. W. (1943). Factors determining national stereotypes. Journal of Social Psychology, 17, 203-219. De Boeck, P., & Claeys, W. (1988, June). What do people tell us about their personality when they are freed from the personality inventory format. Paper presented at the 4th European Conference on Personality, Stockholm. Everts, Ph. P., & Tromp, H. W. (1980). Tussen oorlog en vrede. Amsterdam: Intermediair. Frank, J. D. (1982). Sanity and survival in the nuclear age. New York: Random House. Karlins, M., Coffman, T. L. & Walters, G. (1969). On the fading of social stereotypes: Studies in three generations of college students. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13, 1-16. Kippax, S., & Brigden, D. (1977). Australian stereotyping: A comparison. Australian Journal of Psychology, 29, 89-96. McClintock, C. M. (1988). Evolution, systems of interdependence, and social values. Behavioral Science, 33, 59-76. Meenes, M. (1943). A comparison of racial stereotypes of 1935-1942. Journal of Social Psychology, 17, 327-336. Nuttin, J. (1976). Het stereotiep beeld van Walen, Vlamingen en Brusselaars, hun kijk op zichzelf en op elkaar: een empirisch onderzoek bij universitairen. Mededelingen van de Koninklijke Academie voor Wetenschappen, Letteren en Schone Kunsten van Belgie. Klasse der Letteren, 38(Whole No 2). Peabody, D. (1985). National characteristics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Peeters, G. (1979). Person perception and the evaluative-meaning concept. Communication & Cognition, 12, 201-216. Peeters, G. (1982). Implications of a relativistic evaluative-meaning concept for persuasive communication. In F. Löwenthal, F. Vandamme, & J. Cordier (Eds.), Language and language acquisition (pp. 263-266). New York: Plenum Publishing Corporation. (Reprinted from Revue de Phon‚tique Appliqu‚e, 57, 35-39) Peeters, G. (1983). Relational and informational patterns in social cognition. In W. Doise & S. Moscovici (Eds.), Current issues in European Social Psychology (pp. 201-237). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Peeters, G. (1986). Good and evil as softwares of the brain: On psychological 'immediates' underlying the metaphysical 'ultimates'. A contribution from cognitive social psychology and semantic differential research. Ultimate Reality and Meaning. Interdisciplinary Studies in the Philosophy of Understanding, 9, 210-231. Peeters, G. (1987). The Benny Hill Effect: Switching cognitive programmes underlying subjective estimations of the outcomes of bargains concerning distributions of rewards. European Journal of Social Psychology, 17, 465-481. Peeters, G. (1991). Relational information processing and the implicit personality concept. European Bulletin of Cognitive Psychology, 11, 259-278. Peeters, G. & Czapinski, J. (1990). Positive-negative asymmetry in evaluations: The distinction between affective and informational negativity effects. In W. Stroebe & M. Hewstone (Eds.), European Review of Social Psychology (Vol.1, pp. 33-60). Chichester: Wiley & Sons Ltd. Prothro, E. T. (1954). Cross-cultural patterns of national stereotypes. Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 53-59. Prothro, E. T. & Melikian, L. H. (1955). Studies in stereotypes: V. 15 Familiarity and the kernel of truth hypothesis. Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 3-10. Rommetveit, R. (1968). Words, meanings and messages. New York: Academic Press. Saenger, G. & Flowermans, S. (1954). Stereotypes and prejudical attitudes. Human Relations, 7, 217-238. Schneider, J. (1979). Versöhnung zwischen Polen und Deutschen. Munster: Pax Christi-Schriftenreihe. Van der Pligt, J., & Eiser, J. R. (1984). Dimensional salience, judgment and attitudes. In J. R. Eiser (Ed.) Attitudinal judgment. New York: Springer-Verlag. Wecke, L., Schmetz, W., & De la Haye, J. (1980). Vijandbeeld in de Nederlandse publieke opinie. Nijmegen: Studiecentrum voor Vredesvraagstukken. Wecke, L., Schmetz, W., De la Haye, J., & Vierhout, R. (1981). Vijandbeeld in Nederland. Nijmegen: Studiecentrum voor Vredesvraagstukken. 16 OP AND SP VALUES OF STEREOTYPES: APPENDIX OF 'SELF-OTHER ANCHORED EVALUATIONS OF NATIONAL STEREOTYPES' Guido Peeters N.F.W.O. and K.U.Leuven Laboratory of Experimental Social Psychology Tiensestraat 102, B-3000 Leuven, Belgium 1992 ---------------------------------------------------------------------- Table 1. List of sources with code letter (A, B,..N) --------------------------------------------------A: Child and Doob (1943) B: Everts and Tromp (1980) C: Frank (1982) D: Karlins, Coffman, and Walters (1969) E: Kippax and Brigden F: Meenes (1943) G: Nuttin (1976) H: Prothro (1954) I: Prothro and Melikian (1955) J: Saenger and Flowermans (1954) K: Schneider (1979) L: Wecke, Schmetz, and De la Haye (1980) M: Wecke, Schmetz, and De la Haye (1981) N: Wette (1948) --------------------------------------------------- 17 Table 2. OP and SP values of published stereotypes. ------------------------------------------------------------------------ (Code) = running number and letter mark referring to the source of the stereotype (see table 1) - Date = year indicating (approximatively) when the stereotype was measured - Mean and SD: All adjectives drawn from the stereotypes were (if necessary) translated into Dutch and then rated for OP and SP by two separate groups of 20 judges using the Peeters-method (see previous paper). The ratings were made on 9-point scales which afterwards were transformed into scales ranging from -100 to +100 with 0 as neutral middle. Hence + and - scores reflect respectively +OP and -OP (or +SP and -SP). For each stereotype Means and SD's of OP and SP were computed over the adjectives that constituted the stereotype. If data were available about the frequencies with which adjectives were assigned to the stereotyped group, then N was not simply the number of different adjectives, but each distinct adjective multiplied by the number (percentage) of subjects that had used it in their descriptions of the stereotyped group. This "weighting for frequency" was applied to all stereotypes except those marked by * (from studies C, E, and N in which no frequency data were reported). Notice that SD is an index of homogeity: small SD's indicate high homogeneity of the given stereotype (which means that subjects assigned adjectives with about the same OP or SP value). - SM Class = classification of the stereotype according to the social motives associated with various combinations of OP and SP (see Peeters, 1983). Capitals are used if the OP and/or SP values supporting the classification deviate at least one SD from zero. If they deviate less, the corresponding motive-class is indicated in small letters and between brackets. Meaning of the classification labels: ALT = altruism (+OP) COOP = cooperation (+OP/+SP) IND = individualism (+SP) COMP = competition AGG = aggression (-OP/+SP) (-OP) SADOM = sadomasochism MAS = masochism MART = martyrdom (-OP/-SP) (-SP) (+OP/-SP) For instance, stereotype (001D) -- American autostereotype from 1933-- is marked "IND" because SP = +41, which is more than one SD (=19) above 0, and it is additionally marked "(coop)" because +SP is combined with +OP but the latter amounting only to +20 is lower than one SD (=36) above 0. 18 --------------------------------------------------------------------------STEREOTYPED GROUP OP SP (Code) + Date + Stereotyping Subjects Mean (SD) Mean (SD) SM Class --------------------------------------------------------------------------AMERICANS (001D) 1933 American students +20 (36) +41 (19) IND (coop) (002A) 1938 American students +07 (44) +30 (27) IND (coop) (003A) 1940 American students +09 (43) +29 (37) (coop) (004D) 1951 American students +04 (38) +41 (16) IND (coop) (005J) 1954 American students +01 (38) +44 (23) IND (coop) (006D) 1967 American students 00 (39) +37 (21) IND (007I) 1952 Arab students +16 (39) +30 (21) IND (coop) (008H) 1950? Armenian students +21 (19) +30 (30) COOP *(009E) 1974 Australian students -31 (34) +23 (22) IND (comp) AMERICANS: WHITE AMERICANS (010F) 1935 American black students (011F) 1942 American black students -08 (45) +08 (44) +31 (24) +32 (21) IND (comp) IND (coop) ARABS *(012E) 1975 Australian students -49 (32) +01 (28) AGG (comp) ARABS: POLITICAL LEADERS OF OIL COUNTRIES (013M) 1979 Dutch population sample -63 (38) +09 (29) AGG (comp) ARABS: INHABITANTS OF OIL COUNTRIES (014M) 1979 Dutch population sample -20 (62) +10 (24) (comp) AUSTRALIANS *(015E) 1974 Australian students -03 (43) +11 (32) (comp) CHINESE (016D) (017D) (018D) (019F) (020F) (021H) *(022C) *(023E) 1933 1951 1967 1935 1942 1952 1966 1974 American students American students American students American black students American black students Armenian students Americans Australian students -05 +12 +12 -09 +19 -05 -59 +20 (33) (28) (28) (40) (30) (25) (42) (22) -02 00 +05 -02 +02 -16 +09 +29 (26) (22) (23) (24) (21) (29) (25) (26) (sadom) (coop) (coop) (sadom) (coop) (sadom) AGG (comp) IND (coop) ENGLISH (024A) (025A) (026D) (027D) (028D) (029F) (030F) (031H) (032I) *(033E) 1938 1940 1933 1951 1967 1935 1942 1952 1952 1974 American students American students American students American students American students American black students American black students Armenian students Arab students Australian students +09 +09 +21 +12 +12 +18 +06 -23 -01 +10 (44) (44) (38) (28) (34) (32) (35) (42) (41) (40) +29 +28 +13 00 +16 +15 +11 +05 +22 +17 (28) (30) (23) (22) (29) (22) (25) (25) (28) (24) IND (coop) (coop) (coop) (coop) (coop) (coop) (coop) (comp) (comp) (coop) FLEMINGS (DUTCH-SPEAKING BELGIANS) (034G) 1971 Walloon Belgian students -12 (38) -04 (34) (sadom) FRENCH (035A) 1938 American students (036A) 1940 American students +03 (44) +07 (43) +22 (27) +24 (27) (coop) (coop) 19 (037H) 1952 Armenian students GERMANS (038A) (039A) *(040C) (041D) (042D) (043D) (044F) (045F) (046H) (047H) *(048N) *(049E) 1938 1940 1942 1933 1951 1967 1935 1942 1952 1952 1948 1974 American students American students Americans American students American students American students American black students American black students Armenian students Arab students W German community people Australian students 00 (40) +01 +04 -60 +18 00 +06 +11 -13 -05 +07 +39 -03 (47) (45) (45) (26) (38) (35) (32) (46) (48) (45) (06) (43) +09 (24) +26 +26 +03 +34 +29 +36 +37 +24 +25 +36 +54 +11 (ind) (29) (29) (29) (21) (19) (22) (19) (28) (21) (19) (09) (32) (coop) (coop) AGG (comp) IND (coop) IND IND (coop) IND (coop) (comp) IND (comp) IND (coop) COOP (comp) GREEKS *(050E) 1974 Australian students +05 (32) +06 (13) (coop) ISRAELIS *(051E) 1974 Australian students +04 (41) +27 (30) (coop) IRISH (052D) (053D) (054D) (055F) (056F) (057H) students students students black students black students students -05 -07 -12 +26 +18 -02 (46) (41) (38) (41) (38) (32) +05 +04 +05 +14 +10 -07 (22) (19) (17) (24) (22) (21) (comp) (comp) (comp) (coop) (coop) (sadom) ITALIANS (058A) 1938 (059A) 1940 (060D) 1933 (061D) 1951 (062D) 1967 (063J) 1954 (064F) 1935 (065F) 1942 (066H) 1952 *(067E) 1974 American students American students American students American students American students American students American black students American black students Armenian students Australian students -02 +03 +03 +21 +13 +21 -03 +04 +23 +09 (44) (43) (39) (21) (30) (27) (44) (34) (31) (33) +24 +21 +06 +15 +12 +10 +07 +02 +16 +11 (29) (28) (20) (19) (18) (22) (24) (24) (26) (15) (comp) (coop) (coop) ALTR (coop) (coop) (coop) (comp) (coop) (coop) (coop) JAPANESE (068F) 1935 (069F) 1942 (070A) 1938 (071A) 1940 (072D) 1933 (073D) 1951 (074D) 1967 *(075C) 1942 *(076C) 1966 (077H) 1952 (078I) 1952 *(079E) 1974 American black students American black students American students American students American students American students American students Americans Americans Armenian students Arab students Australian students +19 -26 -06 00 +14 -19 +15 -60 +30 -03 +06 +20 (29) (47) (46) (45) (39) (41) (32) (45) (07) (43) (41) (20) +29 +13 +23 +24 +27 +13 +31 +03 +41 +20 +22 +39 (23) (27) (31) (31) (24) (30) (29) (29) (08) (27) (28) (20) IND (coop) (comp) (comp) (ind) IND (coop) (comp) IND (coop) AGG (comp) COOP (comp) (coop) COOP 1933 1951 1967 1935 1942 1952 American American American American American Armenian LEBANESE (080H) 1952 Armenian students +03 (45) +18 (25) (coop) POLES (081A) 1938 American students 00 (47) +14 (27) (ind) 20 (082A) (083K) (084K) (085K) 1940 American students 1940? Hitlerian doctrine 1963 German high school pupils 1972 Cologne high school girls +03 -43 -52 -24 (45) (20) (14) (28) +13 -21 -08 -30 (27) (14) (20) (27) (coop) SADOM AGG (sadom) MAS (sadom) -09 -11 -62 -28 -19 -20 -04 -10 -04 +03 -52 +02 (47) (47) (27) (54) (56) (55) (54) (56) (54) (55) (50) (39) +20 +17 -17 -07 +11 +06 +23 +21 +18 +20 +10 +29 (30) (30) (23) (36) (38) (38) (38) (36) (36) (20) (30) (27) (comp) (comp) AGG (sadom) (sadom) (comp) (comp) (comp) (comp) (comp) IND (coop) AGG (comp) IND (coop) -54 (42) +02 (25) AGG (comp) -47 (46) +04 (26) AGG (comp) RUSSIANS AFTER INTERVENTION IN AFGHANISTAN (100L) 1980 Dutch pop. sample experiencing R. as military threat -58 (39) (101L) 1980 Dutch pop. sample NOT experiencing R. as military threat -56 (41) 00 (24) AGG 01 (24) AGG (comp) (coop) RUSSIANS (086A) 1938 (087A) 1940 (088N) 1948 (089B) 1948 (090B) 1948 (091B) 1948 (092B) 1948 (093B) 1948 (094B) 1948 (095H) 1952 *(096C) 1966 *(097E) 1974 (098L) 1979 American students American students W Germans W Germans Dutchmen Italians British Norwegians Frenchmen Armenian students Americans Australian students Dutch pop. sample expiencing R. as military threat (099L) 1979 Dutch pop. sample NOT experiencing R. as military threat SPANISH *(102E) 1974 Australian students +14 (27) +06 (14) TURKS (103F) (104F) (105D) (106D) (107D) (108D) -35 -33 -44 -39 -32 -52 -02 -06 -15 -15 -08 -15 1935 1942 1933 1951 1967 1952 American American American American American Armenian black students black students students students students students (44) (40) (39) (37) (35) (25) (21) (27) (15) (21) (20) (21) (sadom) (sadom) SADOM AGG (sadom) (sadom) AGG (sadom) WALLOONS (FRENCH-SPEAKING BELGIANS) (109G) 1971 Flemish Belgian students -31 (40) +23 (24) (comp) --------------------------------------------------------------------------Note: Stereotypes with code E, C, or N (also marked by *) consisted only of lists of traits without including information about the % of Ss that assigned each trait to the stereotyped group. 21