South African Labour Law Newsletter - September 2007

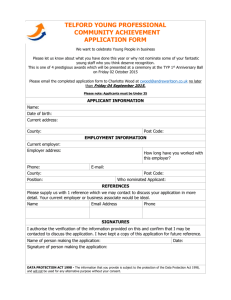

advertisement