International Crisis Theory and the Greek

advertisement

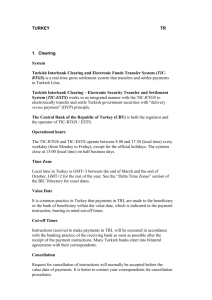

International Crisis Theory and the Greek-Turkish Dispute Over Imia/Kardak Islets: What Lessons for the Future? Yildirim Kayhan, Bilgi University Anastasios Sykakis, University of Essex and Ioannis Tsantoulis, University of Athens 1 Introduction Crisis management is a very interesting topic for an International Relations scholar. It combines elements and notions that exceed the narrow field of International Relations. In fact, this field of Strategic and Security studies manages to integrate elements from Political Science, Psychology, decision-making, even Statistics and Game Theory. However it is even more interesting to apply this aggregated knowledge to the Greek-Turkish dispute. Turkey and Greece were considered to be one of the most traditional pair of enemies ever. Both countries traditionally perceived each other as the enemy, the ‘bad’ and the rogue state of the region. International organizations were always trying to deal with them on an equally pouting; therefore they accepted the two countries as members almost simultaneously (for example NATO, European Council). The GreekTurkish dispute has deep historical, political and cultural roots. The perceptions and the misperceptions are so deep that is difficult to locate them. Turks saw in the face of Greeks the basic opponent in the creation of their modern Kemalist state, whereas Greeks always had the fear of the “enemy from the East” whether this was the Persians or the Ottomans or the Turks. In this turbulent framework Greece and Turkey have repeatedly fought each other many times and reached on the verge of an armed conflict even more times. That said the Imia/Kardak incident of 1996 can be labeled as a natural flow of the troubled Greek-Turkish history. However, the change that took place in the bilateral relations just three years after the Imia/Kardak crisis and had the lethal earthquakes as a starting point created a new, unprecedented dynamics. The purpose of this paper is to present a basic overview about international crises theory, particularly the brinkmanship crisis and apply it to the Imia/Kardak crisis between Greece and Turkey. That said, we will place the Imia/Kardak crisis in the context of International Crisis Theory and we will argue that it was a classical brinkmanship crisis. This crisis was the first after 10 years of a relatively quiet period in the relations between the two countries. It was a very dangerous incident that almost brought the two countries to an armed conflict with tremendous consequences for both of them but also for the whole South-eastern wing of NATO and the EU. Undoubtedly the conflict between two of the most heavily armed countries of NATO could destabilize the whole region. Our purpose is not to put the blame to one of the two countries. On the contrary we intend to examine the crisis under a critical perspective, point out factors that led to its evolution and draw valuable conclusions 2 for the future. We will also briefly refer to the facts that took place during the “cold January” of 1996 and we will try to avoid extensively referring to legal arguments that might exhaust the reader. In our closing remarks, we argue that only the European perspective of Turkey can deter incidents like the Imia/Kardak crisis and we also present some useful, we hope, thoughts. That said, part I of our paper will be the theoretical framework of the paper, whereas part II, after the quotation of the chronicle of the crisis, will deal with the Imia/Kardak crisis in the context of our theoretical findings. Part III includes the identity formation and the role of Media in the Imia/Kardak crisis and our concluding remarks. 3 PART I Theoretical Framework International Crisis Theory: Brinkmanship Crisis The purpose of this section of our paper is to discuss the general “International Crisis Theory”. This is a big challenge for a scholar, because the relative literature is extensive enough so than somebody can delve into all the existing schools of thought and provide many various definitions and conflicting views. However, we will focus on elements that are common to many theoretical approaches and mainly we will mainly try to place the Imia/Kardak crisis among the various theoretical approaches. This paper argues that the Imia/Kardak crisis can be placed in the category of “brinkmanship” crises. International Crisis Theory: What is a “Crisis”? Our starting point is the distinction between ‘international crisis’ and ‘international conflict’. Although the two notions are related to each other they are not identical. More specifically, an ‘international crisis’, is issue-specific and usually focuses on narrower purposes than a conflict. A crisis can often be embedded in a general conflict and this is the case of Imia/Kardak where the crisis was a part of the general Aegean conflict. Consequently a conflict may encompass many crises over different aspects and this is the case of the Arab-Israeli conflict. On the other hand, a crisis can take place without a previous conflict. Crisis, from the political point of view, can be defined as the disturbance of a normal process or as the tangible questioning of another actor’s values, structures etc. A widely accepted definition of International Crises is the one by Hermann (1969:6182). He denotes that crisis “is a situation that (I) threatens high-priority goals of the decision making unit, (II) restricts the amount of time available for response before the decision is transformed, and (III) surprises the members of the decision-making unit by its occurrence. Alexander George (George, 1995:214) denotes that international crises are the product of interest conflicts and occur in situations of 4 threatened war, either because of conscious actions of the engaged parts, or because of incaution. He also points out that the decisions that the parts have to undertake may affect their individual success or failure but also the structure of the current international system. James Richardson (Richardson, 1994:10-12) argues that we can distinguish three different approaches of International Crises: The first is the ‘systemic’ approach, according to which, the crisis is a brief period where the transformation of a system is threatened. The second is the decision-making approach which stresses the importance of the decision making of governments. Brecher and Wilkenfeld belong to this category and they argue that an international crisis is “a situation deriving from change in a state’s internal or external environment which gives rise to decision makers’ perceptions of threat to basic values, finite time for response and the likelihood of involvement in military hostilities” (Brecher&Wilkenfeld, 1982:383). Finally the third category refers to crises with ‘perceptions of high probability of war’. That said, this approach perceives crises as the interactions between two or more governments that may lead to war. It is obvious that this approach bears resemblance to the decision-making approach, because they both imply the important role of domestic politics (governments). However the difference lies in the fact that the third category points out the perception that governmental actions might lead to an armed conflict. However, despite the fact that there are numerous definitions of international crises, this paper argues that the definition that is more suitable for our purposes is the one provided above by Alexander George because it adopts elements from all the three categories that Richardson suggests. There are also various types of crises. The most obvious distinction is the one related to the military capabilities of the engaged parts. The military capabilities of the ‘other’ are a serious factor in the decision making of an actor in crisis environment. From this perspective, we can obtain crises between ‘weak’ states, conventional crises but also nuclear crises. Another type of international crisis is the one defined by the final scope or the target of the engaged parts. In this context, Richard Ned Lebow (Lebow, 1981:25-58) presented three types of crises: the ‘justification of hostility crises’, the ‘spin off crises’ and finally the ‘brinkmanship’ crises, where the Imia/Kardak crisis belongs and this paper mainly examines. 5 Brinkmanship Crisis Brinkmanship is probably the most common type of crisis and it was principally inserted in the field of crisis management by Thomas Schelling. Schelling (Schelling, 1966:91) defined brinkmanship as “a technique of compellation which creates a usually shared risk”. According to Lebow, (Lebow, 1985:180-181) brinkmanship crisis can be developed under certain circumstances. More specifically he denotes four ‘sources’: First is the existence of a threat that can cause a serious disturbance in the current balance of power, second the institutional insufficiency of a state, third is the weakness of leadership which may construct an external crisis in order to gain profit (legitimization, improvement of profile, counterplotting from another serious matter) in the field of internal politics. Finally another factor is the competition of domestic elites about the distribution of power. The brinkmanship crisis is externally expressed by one actor’s challenge of an important commitment of another actor, anticipating that the latter will draw back from this commitment. By doing this, the ‘challenger’ might have various targets. He may aim to demonstrate the other’s weakness and his relative superiority, or he might aim to gain something else that it is not directly expressed (trade-off) or take a privileged position in a forthcoming negotiation, resulting in an effective distributive bargaining. On the other hand, the ‘challenged’ actor has two options: To resist or to back off. Backing off might involve serious side-effects such as losing face, worsening the bargaining capability of the actor, losing internal legitimization and last but not least losing the commitment that was initially challenged. However, if the ‘challenged’ actor backs off, then by definition we do not have a brinkmanship crisis because it takes two to tango. In the case that the ‘challenged’ actor resists (and this is what usually happens) then the crisis escalates, resulting into a brinkmanship situation. It is the degree of effectiveness of this resistance that finally determines the outcome of the situation. If the ‘challenged’ actor resists effectively then the ‘challenger’ has either to withdraw or proceed to an armed conflict. However, a brinkmanship tactic is considered to be successful only and if, the ‘challenger’ gains what he wants without war. In this context, a scholar can notice that brinkmanship crisis bears great resemblance to the ‘chicken’ game. Crisis Management 6 People tend to deal with and resolve numerous crises in their everyday life. Thus everyday life, from the annoying dog of the neighbor up to the serious business problems people negotiate and up to a certain degree have crisis management and resolution skills. However this reveals two big truths about the nature of conflict management: the first is that every situation is manageable and resolvable. The second and most important for our purposes is that there is no specific design or a pattern that can guarantee full success. In other words there is no secure conflict management procedure. Snyder and Diesing (1977:207) argue that “the term crisis management is usually taken to mean the exercise of detailed control by the top leadership of the governments involved so as to minimize the chances that the crisis will burst out of control into war. The statesmen also want to advance or protect their state’s interests, to win, or at least, to maximize gains or to minimize loses, and if possible to settle the issue in conflict so that it does not produce further crises”. The underline meaning of this definition is that when we are talking about ‘conflict management’ by definition we imply a kind of involvement in a negotiation process. All these situations are characterized by certain elements (Lewicki et all, 2003:4-6): First, they are interpersonal, interstate, intrastate, intergroup or intragroup. In other words there are always two or more parties. Second, there is a kind of conflict between them. Third, the parties negotiate only when they believe that this process will leave them better off. Thus, they hope that they will get a better outcome than the current or than what the other party would voluntarily give them. Fourth, the parties prefer, at the present moment, to search for an agreement rather than proceed to an open fight. Fifth, negotiating implies ‘give and take’. All the sides will modify, back off and demand positions and statements. Sixth, the process will include both tangible and intangible elements. The intangibles may encompass values and beliefs, psychological motivations, not lose face and preserving credibility. Therefore, Snyder and Diesing often use the term ‘management’ as synonymous to the word ‘bargaining’. Since negotiation begins, from theoretical point of view we find ourselves in front of the common theories of bargaining. More specifically the parties will have to choose what kind of strategy they will follow. Briefly1, they have two options: the first is the distributive bargaining where parties take offensive positions towards each other, claim value and generally perceive things as a ‘zero- 1 Analytically referring to negotiation tactics exceeds the purposes of this essay 7 sum’ game. The second option is an integrative bargaining situation where parties, have shared interests, create value and generally try to create ‘win-win’ situations. However, after brinkmanship crises it is more likely that parties will find themselves in front of a distributive bargaining, because of the nature of the crisis which involves that one party, on purpose, challenges something that the second party considers important for reasons discussed earlier in this paper. PART II The Imia/Kardak Incident in the Context of International Crisis Theory Greece and Turkey are in a very well known dispute over the legal status and consequently of the exploitation of the High Seas of the Aegean. That said, we often observed tension over the Aegean Sea, since 1974 when Turkey first challenged the status of the sea frontier that divides the two countries. Undoubtedly the Imia/Kardak incident has been (along with the 1987 ‘Sismik’ incident) the most serious crisis that almost resulted in a war between two heavy armored countries and allies in the context of NATO. The Chronicle of the Imia/Kardak Crisis On Tuesday 26 December 1995, the Turkish commercial boat Figen Akat aground in the rocky islands Imia/Kardak, that abstain 3,8 nautical miles from the Turkish coasts and 5,5 nautical miles from the nearest Greek island, Kalymnos, with the western extending in 25 acres and the eastern 14 and the length of the coasts are 613 and 499 metres respectively (see Kouris, 1997:429) The Turkish skipper denied the help that was offered to him from the Greek side on the grounds that he was in Turkish territorial waters and that he had the legal right to ask for the help of the Turkish tractors for the detachment of his boat. On Wednesday 27th of December, the head of the department of the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs Ahmet Bangkouglou accepted the ship to be towed from Greek tractors, but stressed in the advisor of the Greek embassy Alexandros Kougios that “… we should discuss the subject further...” (see Kourkoulas, 1998:28-29) 8 On Thursday 28th of December, the boat was towed by the Greek tractor “Matsas Star” in the harbour of Kioulouk opposite Imia. The next day, Friday 29th December, the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs delivered a verbal notification in the Greek embassy where it analyzed the Turkish arguments related to the status of the islets Imia/ Kardak with a short and frugal way. The notification, that was delivered through the usual diplomatic practice (postal) reported, inter alia, that: “… the rocks Kardak constitute a part of the Turkish territory. Administratively they belong to the province Mouglas and they are a part of the prefecture of Bondrum (Alikarnassos) and geographically belong in the village Karakagia, and are registered in the cadastre of the prefecture Mouglas”(Kourkoulas, 1998:28-29) After the verbal notification nothing happened. At the time there was not any other development from the Turkish side due to the negotiations on the shaping of a new government after the elections of December, while also the Greek political system, was in the maelstrom of internal problems because of the succession of the ill Prime Minister A. Papandreou That was the main reason for the delay of the reaction of the Greek side. Finally the answer came on the 9th January 1996 and rejected the Ankara argument that the rocky Imia / Kardak islands belong to her administrative system reminding to the Turkish side that the agreements of 1932 signed between Italy and Turkey granted the sovereignty of Dodecanese in Italy. Turkey, from her point of view did not answer back, but the Turkish diplomat which received the Greek verbal notification stressed out the Turkish arguments in every detail, creating the impression to the Greek side that they had to deal with a well organised plan from Ankara, (Kourkoulas, 1998:33) After the Greek notification and for about one week no development was noticed. Turkey remained silent. The resurrection of the issue was due to the Greek side, with the briefing of the Ministry of National Defence from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Tuesday 16th January 1996), taking measures of an increased followup of the islets from the Greek authorities (Friday 19th and Saturday 20th January 1996) and the deliberations in Athens of the governmental executives - and the recently elected Prime Minister Kostas Simitis (Wednesday 17th January 1996) - on the latest developments of the subject on Tuesday, 23rd January 1996 (see Xristogiannakis, 1999:37 & Pretenteris, 1996:156) 9 The issue remained strictly an affair between the clerical staff of the 2 ministries of foreign affairs, until Wednesday the 24th of January when the Greek television station ANTENNA TV announced both the incident and also what was discussed between the two states, with the announcement that for the first time Turkey claimed Greek territory. The next day the mass media of Greek followed ANTENNA creating an atmosphere of fear and panic in the public. In Turkey the beginning was made by newspaper Houriet on Thursday 25 th January, which revealed every detail of the issue. The midday of the same day the mayor of Kalymnos with the governor of the police department of the island visited the Imia / Kardak islets – whether they had the authorisation of the Greek government or of any Minister, or not, remains unknown– and they raised the Greek flag in front of television cameras (Xristogiannakis, 1999:37, Pretenderis, 1996:156, Kourkoulas, 1998:36) while on Friday the Greek Minister of Foreign Affairs confirmed the exchange of verbal notifications between the two sides (Giallouridis, 1997:317) On Saturday 27th of January a team of Turkish journalists of the newspaper Huriet from the outlier of Huriet Group in Smyrna reached Imia/Kardak, lowered the Greek flag and simultaneously raised the Turkish one, taped that action and broadcasted it on the TV station that belongs in the same group with Hurriet, giving first class occasion of projection, as the channel was just created and needed the big success. The abstraction of the Greek flag became perceptible from the Greek patrol boat “Panagopoulos” early in the morning of the 28th January and the afternoon (19:00) a Greek contingent of the Martial Navy disembarked on the two rocky islands of Imia/Kardak in order to raise and safeguard the Greek flag. Monday, 29th of January the Greek ambassador in Ankara, Dim. Nezeritis, was called in the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affair and he was delivered verbal notification that disputed the legal regime of rocky islands. There were also proposed negotiations, not only on the Imia/Kardak, but on the delimitation of marine borders. Concerning the Imia/Kardak crisis, he was asked for the removal of Greek military and the lowering of the flag. The afternoon of the same day Washington recommended sang-froid. While at 21:00 the National Security Council of Turkey 10 was convened. Prime Minister T. Ciller demanded the retirement of the team of commandos and the lowering of the Greek flag2. At the dawn of the 30th January the situation around the Imia/Kardak islets had become dramatic. At 05:00 in the marine region of Imia/Kardak the Greek force becomes, at statement of Greek defence minister, “equivalent and somehow increased” (Giallouridis, 1997:317) The morning of the same day on January the 30th a meeting took place with the participation of the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of Turkey with the Greek Ambassador in Ankara Dimitrios Nezeritis. The Turkish dignitary asked for the return to the Status quo ante and the retirement of the boats, the men and the national symbols from the region. After the midday both countries had assembled big forces round the rocky islands Imia. Simultaneously there were telephone discussions from the Americans with both the Greek and Turkish side. On the 31st January, 02:00 there are breaking news for occupation of second unguarded rocky island from Turkish commandos3. At 03:00 a martial navy patrol finds certain traces. At 04:00 Holbrook confirms the occupation of the rocky island. At 05:00 through telephone discussions among Washington - Athens – Turkey, a process of disengagement was agreed with guarantors Mr. Holbrook and Christopher, beginning at 6 o’clock. At that time the helicopter that was taken off in order to confirm the occupation of rocky island falls in the sea. The impression that was created in Greece, enhanced by Media insinuations, was that the Turks shot down the helicopter. However the Turkish side denied every involvement in the accident and stated its deep regret about it. Between 06:00 - 09:30 there was a withdrawal of the naval forces of the two states with a “step by step” process. At 10:30 political storm in Athens burst out between the Government and the Opposition (see Giallouridis, 1997) She stated “We do not have to give even a little rock from our land…it is out of the question for Turkey to let other to encroach our land…we will arrange this issue like we handled the Avrassia crisis…”. She also mentioned that Turkey will make every effort to settle the crisis in a peaceful manner, but she also said that Turkey is ready to use her power, including the use of violence, in case there will not be a settlement of the crisis. 3 The proposal for the capture of the western Imia/Kardak islet was an idea of the Turkish Ambassador Inal Badou who believed that such a move would create the conditions for a balanced and equal retirement of both parties without any use of violence. 2 11 Consequently this episode that almost led the two countries to armed conflict4, ended with the mediation of USA, but Turkey did not resign from its claims in the Aegean. On the contrary it was extended to other islets and islands as well. Brinkmanship Crisis: The Imia/Kardak Case The Imia/Kardak case accomplishes all the elements of a dangerous brinkmanship crisis. Brecher argues that an antagonistic diplomatic relationship between two states is likely to become a completely crystallized crisis when (1) this diplomatic relationship is a part of a protracted conflict, (2) there is geographic proximity, and (3) there is a strategic, economic, political, and/or cultural heterogeneity between the adversaries. The Greek-Turkish dispute over Imia/Kardak satisfies the above conditions: it is the result of a protracted tension in the Aegean Sea, the two countries are neighbours, so there is geographic proximity and finally there are elements that differentiate the strategic, economic, political and cultural status of the two countries. In the Imia/Kardak case, Turkey was the ‘challenger’ and Greece was the ‘challenged’ part. In addition to this, a scholar should also examine the domestic political situation in both countries. Turkey, at that moment, had serious internal problems. The Ciller administration was under extreme pressure because of its alleged relationship with the local mafia. Turkish economy has been extremely weak and the need to find an ‘escape goat’ was immediate. What happened later offered the perfect internal legitimization to the Cilled administration, united the people but also abstracted them from their previous concerns and probably from their real problems and finally demonstrated the relative military superiority of Turkey. Greece, on the other hand, had a new Prime Minister (Mr Simitis had only some days earlier followed on Mr A. Papandreou as the Prime Minister) that was trying to shape his government and consequently the reaction was not as rapid as it should. As we noted earlier, the Greek government under the pressure of the public opinion and the media sent marines to replant and protect the islets. Turkey responded, Greece send 4 That incident and the conflict for a little islet in the Aegean created a curiosity at the International Agencies that described Imia/Kardak as “tiny, largely, backend outcroppings of rock inhabited only by goats and rabbits…so small that they figure merely as footnotes on sailing charts”, at James Walsh reported by Anthee H. Carassavasiathens, J.F.O. Mcallister/ Washington and James Wilde/Istanbulk, “Conflicts Brinkmen on the Rocks, Greece and Turkey stop just short of War over a pair of stony outcroppings in the Wine-Dark Sea”, TIME International, February 12, 1996, Volume 147, No.7, http://www.time.com/time/international/1996/960212/conflicts.html , 14.06.2001 12 the navy and the crisis had already been escalated. At that point, Greece quickly asked for the assistance and the mediation of the United States and European Union. This happened mainly because Greece acknowledged its relative military weakness vis-àvis Turkey but also, and this is a crucial element, because it was the defender of the status quo. Mediation in International Crises and the Imia/Kardak Case: Third Parties in the Crisis. Wherever there is mediation in a crisis, there is always and underlying interest from the mediator’s point of view. The mediator may have a direct interest to resolve the crisis, either because he is afraid of his own interests from a possible spill over or because he wants to preserve the status quo. The mediator may also have indirect interest to resolve a crisis because he wants to demonstrate his abilities and gain face, improving his relative position in the conflicting parties. In the Imia/Kardak case, United States successfully mediated and resolved the crisis. Thus, it should be noted that the crisis happened in a unipolar moment, with the USA being the sole superpower. From a theoretical point of view, superpowers do not tend to change the status quo and the structure of the international system, unless they are directly affected by this change. Turkey is a pivotal state (see Chase et all 1999:159-217) for the United States, whereas Greece is a stable ally of the USA, a member of the EU and the most important regional player in the Balkans. In addition to this, Turkey and Greece are allies in the context of an alliance led by the United States. It should be noted that many times in the past, NATO was called to mediate in a Greek-Turkish dispute. This dispute has always been a factor of instability in NATO’s South-Eastern division. This explains why the United States had a direct interest to preserve the status quo in a very sensitive, from a strategic point of view, area. In addition to this, given the inability of the EU in these aspects, the USA had a perfect opportunity to reaffirm its dominant position in the region. In sum, the USA had three specific interests: (1) to preserve the status quo, (2) to preserve the integrity of NATO, (3) to preserve its dominance in the region. As pointed out earlier, Greece, the weakest part, was the one who asked for mediation. The sequence of the moves in the crisis has been like this: Turkey made the first move (planting the Turkish flag on Imia/Kardak islets), Greece responded (by sending marines and naval forces and replanting the Greek flag), Turkey escalated (by 13 occupying the second rock). This was the point that Greece asked for mediation. This is understandable because Greece reached its zenith point in the crisis. Greece understood that a further move would probably cause another move by the Turkish side. Greece’s move can be judged as correct. Taking into account the past reactions of Turkey, but also its bad internal conditions Greece took a painful, in domestic affairs terms, decision. What is interesting here is why Turkey accepted the mediation, since it was a relatively more powerful state and furthermore, as the facts took place, it was in the pleasant strategic position to be able to challenge and carry out another-last-move that would bring Greece in a terribly difficult position. The answer is that Turks knew that they had already achieved what they wanted. The mediator, Mr Richard Holbrook asked the return to the status quo ante before January 1996 and the removal of any flags or military. Despite the fact that at the moment Greece had the military superiority in the area, mainly because of an impressive gathering of its navy in the area, it refused to answer to the occupation of the second rock because this would create a much more unbearable cost and promised that it would not use force. On the other hand, Turkey did not respond anything to the American mediator and the two countries started a step-by-step withdrawal from the area. Under this perspective, we can argue that Turkey played the brinkmanship card excellent and has been the ‘winner’ of this incident. Greece, on the other hand failed to support its deterrence strategy and make it liable, by declaring a clear and strong ‘no’ to the Turkish claims at any point during the crisis. More specifically, Greece did not try to increase the cost of escalating the crisis for the Turkish side by declaring to every destination why it reacts the way it reacts. In this way, a neutral observer could see the Greek side, aggregating military power around some rocks, without really understanding why. In addition to this Greece, by aggregating power gave the impression that it is trying to impose something in the area and not protect itself and deter the ‘challenger’. Turkey, on the other hand managed to prove that the common defensive doctrine between Greece and Cyprus cannot be supported in practice because Greece could not even handle a crisis in its own territorial waters. Moreover, and this was probably the biggest benefit for Turkey, while the Turkish government’s target was to gain internal legitimization, empower its position and improve its negative image, they managed to do something much more important: To establish the rhetoric of “grey zones” in the Aegean. 14 The Presence of the EU If a scholar examines the reactions of the European Union and its institutions, he/she will probably conclude on the following: First, there was a differentiation in the attitude of the EU institutions. Second, there was not any collaboration among the institutions. Third, there was an absence of a cohesive policy by the EU. Fourth, the intergovernmental body, the Council of Ministers took position on this issue late (see Perrakis 1997:140-152). The first institution that reacted was the European Commission (E.C. 07.02.1996) with a statement on the 7th of February 1996, and undoubtedly expressed its political solidarity to Greece. It is remarkable that, the European Commission after the meetings of the Greek Prime Minister with its President Santer and the minister of Foreign Affairs Pangalos with Commissioner Van Der Broek (on the 11th of February) expressed the opinion that the International Court is supposed to undertake an important role on the settlement of the conflict. Moreover President Santer declared that the customs union of EU - Turkey as an overall agreement includes also the respect of principle of good neighbourhood on behalf of Turkey. On the contrary, the, at that time, chairing the Council of Ministers, Mrs P. Agnelli did not react in the same way. There was neither convened any special meeting, nor something else. Unlike the Council, the European Parliament52 reacted rapidly and in its resolution on the 14th of February 1996 (Valentine’s Day) supported that the Greek borders are external borders of EU. It repeated the same position also on the 19th of September 1996, underlining the need of respect of the principles of International Law, while it placed also conditions for the financing of Turkey. Under such circumstances, the behaviour of Council was rather confusing. For one and a half month after the crisis did absolutely nothing. On February 1996 in the Council of General Affairs there was a reaction - discussion, which led to a drawing of a text which, at the end of the day, did not become acceptable from the British Delegation and therefore was rejected. Finally in July 1996 the Council formulated, for first time officially, the official position of the European Union (see Perakis, 1997:150-151). However this political statement of July 1996 is of crucial importance for the Greek side. For the first time in an official text the European Union expressed its will, apart from the 52 European Parliament, Joint motion for a Resolution (Rule 37(2)), DOC_EN/RE/295/292863, 14 February 1996 15 verbal expression of solidarity, and reported the basic principles of International Law and that the dispute should be resolved in the context of The Hague. However, we need to mention the inability of the EU to handle a crisis in its own borders. The EU once more demonstrated its lack of an operational mediation mechanism and it would not be far away from the truth to say that if it hadn’t been for the USA to mediate things would turn out very different. However we should also mention that Greece is also to blame for this, because it did not state the situation clearly. If Greece had done this, by stating a clear ‘no’ to the Turkish claims and simultaneously communicate the situation to the international community, including the EU, it would make its deterrence ability more credible and it would also increase the cost of escalation for the Turkish side. The Imia/Kardak Crisis in the Context of the General Greek-Turkish Dispute It is hard for a scholar who is not Turkish or Greek to understand why two countries found themselves on the brink of war about some rocks. However, the roots of the general Greek-Turkish dispute are much deeper and somebody could argue that the Imia/Kardak incident is the peak of the iceberg. Both the political and legal argumentation of the two sides about Imia/Kardak can be placed in the general framework of the Greek-Turkish dispute. In the following lines we intend to present and critically explain the argumentation of the two sides, not only limited in Imia/Kardak, but in a more general framework, whenever necessary. We will follow a comparative way of analysis, where the argumentation of the one side will be answered by the other side. However we will try to this briefly because the purpose of this paper is not to delve into a legal argumentation. We will start with the argumentation of Turkey which is the country that has been challenging the status quo in the Aegean Sea. The Imia/ Kardak crisis-and the consequent claims about the existence of “grey zones” that Turkey inaugurated afterwards-constitutes the escalation of the Turkish claims and their qualitative upgrade as it was actually the first time that Turkey questioned part of the Greek territory while there were also issues of legal contestation of both International Treaties and the Law of sea raised and indirectly aimed at the change of the status quo in the Aegean area. 16 The main argument about the Imia/Kardak islets was to whom these rocks belong to. The issue is a ‘fact based’ one. Turkey names it Kardak, Greece names it Imia. For Turkey they are rocks for Greece islets. Both parties claim that these formations belong to them respectively. Turkey recognizes the 1947 Paris Peace Treaty as a legal document. This Treaty (article 14) enumerates the islands to be transferred under Greek sovereignty one by one. Thus, according to Turkey this document is explicit and only the status of these islands that are enumerated in the Treaty is clear. Therefore, Turkey argues that every island or islet or rock that is not enumerated in the document is a matter of negotiation between the two countries. This is the rhetoric of the existence of ‘grey zones’ in the Aegean Sea. Specifically about Imia/Kardak, Turkey also argues that the Aknara Agreement of 1932 between itself and Italy, which settles the maritime borders between the two countries, never entered into force because a) it was not ratified by the Turkish Grand National Assembly and b) it was not registered with the Secretariat of the League of Nations. Thus, this document does not have any legal effect. In addition to this Turkey argues that there has been a “fundamental change of circumstances”. That said, Turkey denotes that all the previous agreements took place in a pre-World War II environment and that the Italian-Turkish Agreement of the 4th January 1932 and the Process verbal of the 28th of December 1932 “became an object of negotiation in the frames of special political situation that prevailed at the pre Second World War period in the region” (see ELIAMEP 1996). Finally Turkey’s last argument is the geographic proximity of the Imia/Kardak islets. Turkey claims that the islets are adjacent to the Asiatic mainland and located only 3,8 miles away ( see Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Legal Backgrounder on the Kardak Crisis in a Nutshell”) whereas the nearest Greek island, Kalymnos, is 5,5 miles away. Turkey acknowledges the existence of a small island called ‘Kalolimnos’ which is depended on Kalimnos and only 1,5 miles away from Imia/Kardak but argues that the latter cannot be “depended on a depended islet”. Greece on the other hand, refers to the Lausanne Treaty of 1923. According to article 12 of the Treaty the Islands of the Eastern Mediterranean are ceded to Greece. Greece argues that the enumeration of the islands is only indicative5. On the contrary, Article 12 of the Lausanne Treaty actually says that “…..regarding the sovereignty of Greece over the islands of the Eastern Mediterranean, other than the islands of Imbros, Tenedos and Rabbit Islands, particularly the islands of Lemnos, Samothrace, Mytilene, Chios, Samos and Nikaria, is confirmed, 5 17 the islands ceded to Turkey and Italy are explicitly enumerated 6. Specifically about Imia/Kardak islets, Greece refers to the article 15 of the Treaty according to which Turkey renounces in favour of Italy a number of islands (enumerated in the document) but also the “islets depended thereon” (Lausanne Treaty, Article 15). Imia/Kardak islets are considered to be, by Greece, depended on Kalymnos island. The Greek argumentation also denotes that Turkey renounced in favour of Italy (therefore to Greece, as a successor to Italy state) all its rights to the islands located more that three miles away from the Asiatic coast, whereas Imia/Kardak is located 3,8 nautical miles away. About the non registration in the League of Nations, Greece argues that this has been a typical action, of technical nature, targeting to the publicity of diplomacy and had no crucial importance. On the Turkish argument that the document was not ratified by the Parliament, Greece argues that there were at least three occasions 7 where Turkey recognized the existing status quo, whereas from 1923 or 1932 up to 1974-75 the sovereignty of Imia/Kardak or of any other island or islet or rock was never questioned or challenged. As far as the argument about “fundamental change of circumstances” and geographical proximity is concerned, Greece refers to the International Law and to the Vienna Convention on the Law of the Treaties (article 62) according to which “a change of circumstances cannot be invoked by a state as a pretext on which to terminate or to retire from a treaty, if this treaty establishes a frontier”. Finally the Greek answer to the Turkish argument about the geographic proximity of Imia/Kardak to the Turkish mainland is that no geographic criteria can be superior to legally binding Treaties. Greece also argues that Imia/Kardak islets are very close to Kalolimnos which is under the administrative authority of Kalymnos and that Turkey insists on using the geographical characteristics of the Aegean Sea whenever they seem to be in its unilateral interests. Part III subject to the provisions of the present Treaty respecting the islands placed under the sovereignty of Italy which form the subject of Article 15. 6 Article 12 “…Except where a provision to the contrary is contained in the present Treaty, the islands situated at less than three miles from the Asiatic coast remain under Turkish sovereignty” 7 Letter of the Turkish Minister of Foreign Affairs on January 3, 1933, verbal note on November 20, 1935, letter of the Secretary General of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on September 26, 1936. 18 The Role of Media in the Greek-Turkish Dispute: Conclusions from the Imia/Kardak case. Our analysis so far in this paper was based on rationalistic accounts about crisis theory and management. Rationalism supports the view that identities and interests are autogenous and pre-given. We accepted, for our purposes, that the interests of the two parties were exogenously given and all that the two countries did was to pursue them strategically. It is also commonly accepted that there is a Security Dilemma between the two countries. However, interests are not exogenously pregiven. They can be shaped by institutionalized norms and by how actors perceive them. Interests are inherent in the structure of a society, embedded in its identity; they are cultivated during the process and the evolution of this society and cannot be seen out of its context (see Wendt, 1994 & Reus-Smit 2001). Therefore they can easily change if society changes. Security Dilemma, based on the feelings of insecurity and uncertainty (Jervis, 1978:167-215) that an actor feels when the ‘other’ increases its security, is considered by neo-realists to be always present in world affairs. But is this true in contemporary international system? An increase in Iran’s power may cause serious concerns in the USA but will an increase in UK’s power cause the same fear? It is obvious that there is something in the middle that differentiates the two cases. If a state or group of states perceive others as friends, or as non-threats, then the Security Dilemma can be solved. In other words, we could argue that instead of treating uncertainty as a constant (neo-realism) we can treat it as a variable. The role of identity formation is very crucial concerning the Greek-Turkish dispute and can explain the current hostility. Tajfel (1981:255) argues that identities perform three necessary functions in a society: They tell you and others who you are and they tell you who others are. Thus, identities imply a particular set of interests and preferences and consequent actions. Turkey and Greece have, as far as their bilateral relationship is concerned, shaped their identity based on being the opposite of the other. Historical and political reasons have certainly played an important role in this, and the result is that Greeks and Turks were perceived to be like black and white colours. Security Dilemma in the Aegean can be solved, theoretically speaking, if the two countries change the way they perceive each other. Mass Media are considered to be one of the most, if not the most, important factors in shaping the perceptions of the public opinions. Under this perspective it will 19 be interesting to briefly examine see how the Media reacted in two cases 8: The Imia/Kardak crisis of 1996 and the earthquakes of 1999. The role of the Media has been extremely important during the Imia/Kardak crisis. In a large degree the Media ‘helped’ to the escalation of the crisis. It is admirable to note that the crisis was escalated because of a stupid kind of joke when some Turkish journalists from Hurriyet went on Imia/Kardak and changed the flags. Before this, the Greek flag was planted on Imia/Kardak by the major of Kalymnos under huge media coverage. In addition to this the movement of the Greek navy forces towards Imia/Kardak was broadcasted on a Satellite TV network! The mediation that prevented the war between the two states did not prevent the war between the Media. Actually the messages that the Media of the two countries exchanged had been extremely aggressive and offensive. In this context, Turkish media presented that Greeks as hysteric and paranoid people and to be accused for causing a crisis, triggered by their ambition to fully exploit the Aegean Sea (see Tufan Turenc, Hurriyet, 31/10/1996). Turkish media also pointed out the ability of the Turkish army which “can take over the Greek islands in 72 hours” whereas “if the army takes over Western Thrace it will be hard to guess where it will stop, Thessaloniki or Athens” (see Sedat Sertoglu, Sabah, 02/02/1996). Greek media on the other hand, referred to the superiority of the western civilization based on the culturally different and Asiatic orientation of Turkey, instead of the European Greeks. In this context the Turk was the ‘barbarian’, ‘uncivilized’ Other and distant to the Greek-European identity (see for example, “Adesmeftos Tipos” 26/01/1996). Greek media also made some silly jokes about the fact that a woman (Mrs Ciller) was the Prime Minister of Turkey at the time by referring to the position of woman in traditional Islamic societies (like if it is different in traditional Christianity). From the above it is obvious that both parties tried to present the relative physical weakness and inferiority of the ‘Other’. Greek media presented Turks as nationalists and Turkey as a revisionist power while the Turkish media blamed Greece 8 Many of the references used in this part are from Aggelopoulou, F., Retsa, P., Psillaki, A., “Mass Media and the Greek-Turkish Dispute”, published on the personal web page of Mr. George Panadreou, www.papandreou.gr 20 for causing a tension in the Aegean for domestic consumption reasons, but also pointed out the lack of effective governance in Turkey. However the reaction of the media was significantly different in the case of the earthquakes that caused many victims in both countries. Greece was on of the first countries that sent rescue teams in the earthquake that took place in Turkey on the 17th August 1999. The same happened when Turkey sent rescue teams during the earthquake in Athens on the 7th September 1999. This fact caused comments of relief and astonishment in the international community, feelings that were reflected in the daily international press of that time. Strictly in the two countries, the feelings of hostility and aggressiveness of the Imia/Kardak period gave their position to feelings of solidarity. The human tragedy that followed the earthquakes managed to do what politics were not able to do for years. The two peoples sent messages of peace and friendship that could not remain hidden from the politicians. The Media could not do anything but follow and enhance the same spirit of solidarity. The ‘Citizen’s Diplomacy’ of ‘Earthquake Diplomacy’ that followed resulted in many ‘Low Politics’ agreements but also to the Helsinki Summit and the Greek ‘Yes’ to Turkey’s European route. Turkish and Greek names that were used in order to reduce the ‘Other’ are now used to express feelings of sorrow and solidarity. Greek newspapers accused the politicians of the two countries and pointed out that there is nothing to separate the two peoples and that despite the different religions, Greeks are praying for the Turks (see “Ta Nea”, 18/08/1999). Greek newspapers also denoted that “we are spending millions for weapons, but what we felt something that we had never felt before when we saw the Turkish mothers crying for their children (see Stergiou Anna, “Eleytherotypia”, 19/08/1999). The Turkish side reacted in the same way. The 30th of August is a National Celebration for Turkey (buyuk taaruz) when usually the TV shows how the Turkish army defeated the Greek one. However the help that Greeks provided prevented the projection of these shows. (see Ayten Gundogdu, “Identities in question: GreekTurkish relations in a period of Transformation?”). These feelings became stronger after the Athens earthquake. Milliyet wrote that “a big number of Turkish people tried to find out what happened in Athens, whereas they were asking how they can help (see Milliyet, 8/9/1999). The Secretary General of AKUT (Turkish rescue team which rushed to help the Greek authorities) stated that “the Greek people first gave the opportunity to create a warm relationship and we want this to be continued” and that 21 “we are here to built a bridge of love and save lives as the Greek EMAK did in Turkey” Conclusions: Prospects for the Future. Can the EU Become a ‘Bridge Over Troubled Waters’? The Imia/Kardak incident has been the natural continuum of a general GreekTurkish dispute over the Aegean Sea but also the Cyprus issue. It was the zenith of the traditional hostility between the two countries and had all the elements of a brinkmanship crisis that almost led to an armed conflict. We argued that, from a theoretical point of view, the Imia/Kardak incident had all the elements of a brinkmanship crisis: First, there was a threat that could cause a serious disturbance in the current balance of power in the area, since two members that support the Southeastern flank of NATO were about to fight, second there was institutional insufficiency in Turkey which allowed the deployment and the escalation of the crisis, third, there was weakness in the Turkish leadership at the moment and they were trying to gain profit and counterpart public opinion from other matters. Greek leadership was also vulnerable at the moment because Mr Andreas Papandreou was in the hospital and his successor Mr. Kostas Simitis had been only elected some days before the incident. All these verify the existence of brinkmanship crisis. Another important factor that led to the escalation of the crisis has been the traditional hostility between the two sides and mainly the perceptions about the other that exist in the two countries. These perceptions, expressed by the media and reflected on peoples minds, let no other choice to governments but to confront each other and engage in the crisis. Last but not least it was the lack of communication along with the bad interpretation and the estimation of the messages and the intentions of the other side that also escalated the situation. This is a crucial point for avoiding future crisis. The establishment of stable and sincere communication channels, preferably direct channels without the intervention of third parties, would ease the discussion about topics that used to be taboos for the two countries and would construct and establish mutual feelings of trust and cooperation. Whereas the elements and the strategic movements of the crisis were analyzed earlier in this paper, we have to point out some possible prospects for the future of the bilateral relations. A future, that we hope it will be developed under the umbrella of the European Union. Since Helsinki, Turkey has made a remarkable progress in its 22 attempt to align itself with the European acquis communautaire. The landmark in this route was last December of 2004 when Turkey got the date for the beginning of negotiations about its accession to the EU. Of course this route is long and extremely difficult whereas it is also sensitive and a matter of approval by the peoples of the EU. It is estimated that Turkey needs at least 10 years to become a full member, while even about this full membership the conclusions of the Council are ambiguous, since it is stated that accession is ‘the final target’. However, the contemporary relations of the two countries, at least a big part of it, are now transformed to a Europe-Turkey matter. Thus we should deal with it in this context. Under this perspective, there is a high correlation between the European prospects of Turkey and its relationship with Greece. An increasingly pro-European Turkey means more and more peaceful Aegean Sea while whatever steps backwards could cause new tension. Of crucial importance is considered to be the de facto recognition of the Cypriot Democracy by the Turkish Government by the 3rd of October, the latest, which is a precondition for the beginning of the accession negotiations for Turkey. However it is expected that directly or indirectly Turkey will recognize the ten new countries, including Cyprus. Strictly in the field of bilateral relations, after the hard and conditional ‘yes’ that Turkey got last December there are mainly two possibilities. The first one is that Turkey will stably continue its long route to Europe and will eventually become a member at the end. If this is the case, then it is expected that there will not be any serious tensions between the two countries and bilateral relations will be further normalized. If, however, this route will be interrupted by any factor, e.g. a change of government in Germany, a referendum in France, or even Turkey’s domestic politics, then we expect a new tension in bilateral relations. It is expected, that even if Greece (or Cyprus) is not directly responsible for a setback in Turkey’s European prospects, it will probably become the scapegoat for any Turkish administration. However, we consider that Greece’s position is a bit tricky. That said, it is easy to understand that incidents like the Imia/Kardak crisis should be examined in accordance with Turkey’s European future but also in accordance with the final settlement of the Aegean dispute. Many scholars, especially in Greece support the view, that since we lived so far with the Aegean problem we can live more with it and let time heal the wounds with the ‘invisible hand’ of the European security governance. These scholars support the view that the more Turkey becomes more and more pro-European the most it will be eager to solve the Aegean issues in compliance with International Law. In this 23 context, they denote that Greece should not pose any strict deadlines to Turkey and let time do the job. However, in this paper we slightly differentiate ourselves and we argue that there should be a deadline for bilateral talks about the final settlement of the Aegean dispute. Our basic argument about this is based on the dubious European future of Turkey. Unfortunately the European Council of December 2004 did not produce a clear ‘yes’ and it did not clearly stated that the end of the negotiation process will result in the full accession of Turkey. To put it simpler, this ‘open-ended’ process creates a ‘butterfly effect’. For example, a future governmental change in Germany, or a negative referendum in France or another European country might cause extra difficulties to Turkey and lead not to the full membership but to a kind of special relationship. This will cause tension in Turkey and it is difficult to predict the potential spill over and the side-effects to Greece or Cyprus. For these reasons, we argue that there should be a deadline which will function as a guarantee for the Greek side but also as a proof of good will for the Turkish side. In other words, if somebody could guarantee that Turkey will eventually become a full member of the EU, then we do not really need deadlines or whatever might cause difficulties or strict timetables. If however, there is a chance that Turkey will not manage to become a full member, then there should be a deadline. This deadline should not be a strict one and for example it could coincide with the period before any referendums in Europe or the final decisions of the council concerning Turkey. This would both give enough time (almost 10 years) to both countries to reach a solution but would also become a guarantee for the final settlement of the Aegean dispute. However, the common denominator of both cases is that Greece should strongly and sincerely support Turkey’s European route, both in bilateral level with the transfer of European ‘know-how’ and at the EU level with the full support of Turkey in the European Institutions Consequently, it is easy to understand that Turkey’s stable European direction and the perspectives of a perpetual democratization that the accession creates, is the best possible development concerning the ‘troubled triangle’ between Turkey-GreeceCyprus, for the peoples of these countries but also for the stability of the whole region. The entrance into the European security governance area would mean, for the Turkish people, even more democratic institutions (freedom of expression, less influential army, etc) and political stability (respect and protection of minorities, 24 women rights) as well as economic prosperity, which is equally important for a country with huge economic differences among the population. A European Turkey would be extremely important for Greece as well. It would mean that there is a Turkey more democratic thus less aggressive. In this case of course we would have less, if any, tension over the Aegean, peaceful settlement of any bilateral dispute and two neighbouring countries that can productively cooperate for common targets and create rather that claim value. The settlement of the Turkish-Greek dispute and the cooperation of the two countries would spill over to the whole region; eliminate a source of perpetual conflict, thus establishing stability, prosperity and cooperation. References Aggelopoulou, F., Retsa, P., Psillaki, A., “Mass Media and the Greek-Turkish Dispute” Brecher, M., & Jonathan Wilkenfeld, Jonathan, “Crises in World Politics”, World Politics, Vol.34, No. 3, 1982, pp. 380-417, p. 383 Chase, R., Hill, E., Paul Kennedy, P., (1999) “The Pivotal States: A new framework for US policy in the developing world”, Norton, (New York), pp. 159-217. ELIAMEP (1996), “Déclaration de la Commission” in “The rock islands of the East Aegean” ELIAMEP (1996) “Verbal Notification of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs about the rock islands in Aegean, 29th January 1996”, Yearbook of Defence and Foreign Policy, ELIAMEP George L. Alexander, & Gordon A. Graig, (1995) “Force and Statecraft: Diplomatic Problems of Our Time”, Oxford University Press, (Oxford), p. 214 Giallouridis, X. (1997), “The Greek-Turkish Conflict from Cyprus to Imia 19551996: The View from the Side of the Press, Publications Sideris, Athens, p.317 Hermann, F., Charles, “International Crisis as a Situational Variable”, in J.N. Rosenau, (ed.) “International Politics and Foreign Policy”, New York: Free Press, 1969, pp. 61-82 Jervis Robert “Cooperation Under the Security Dilemma”, World Politics, Vol. 30, No. 2, 1978, pp. 167-215 Kouris, Nikos, (1997) “Greece - Turkey, the 5 year ‘War’”, Livanis, Athens, p. 429 Kourkoulas, Alkis, (1998) “Imia, A Critical Approach of the Turkish Factor’, I. Sideris, p.28-29. 25 Lebow, Richard, Ned, (1985) “The Deterrence Deadlock: Is There A Way Out?” In Robert Jervis, R., Richard N. Lebow, R.N., Janice Gross Stein, (eds.) (1985) “Psychology and Deterrence”, John Hopkins University Press, (Baltimore and London), pp.180-181 Lebow, R.N., (1981) “Between Peace and War: The Nature of International Crisis”, John Hopkins University Press, (Baltimore), 1981, pp. 25-58 Lewicki, R.J., Barry, B., Saunders, D.M., Minton, J.W., (2003) “Negotiation”, McGraw-Hill, p.4-6 Perrakis S., (1997) “The European Union and the Imia Crisis”, at Istame Gala, April – July 1997, ISTAME Publications, p. 140-152 Pretenteris, I.K., (1996) “The Second Change-Over, p. 156. Reus-Smit Christian “Constructivism” in Burchil Scott et al “Theories of International Relations”, Palgrave, 2001, pp. 209-230 Richardson, James, “Crisis Diplomacy: The Great Powers since the mid-nineteenth century, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, p. 10-12 Schelling,Thomas (1966), “Arms and Influence”, Yale University Press, (New Haven), p. 91 Snyder, Glen & Diesing, Paul, (1977) “Conflict among Nations”, Princeton University Press, (New Jersey), p.207 Tajfel Henri, (1981), “Human Groups and Social Categories: Studies in Social Psychology”, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, p.255 Wendt Alexander “Collective Identity Formation and the International State”, American Political Science Review, Vol. 88, No. 2, 1994,pp. 384-396, Xristogiannakis G., (1999), “The transformation of the rock islands Imia to Kardak”, Strategy, February 1999, pp.37 Newspapers Tufan Turenc, Hurriyet, 31/10/1996 Sedat Sertoglu, Sabah, 02/02/1996 Adesmeftos Tipos” 26/01/1996 26