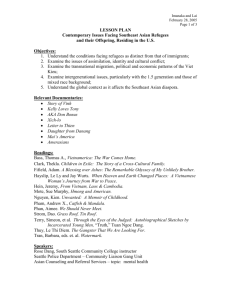

Facilities for graduate study, research, and language training were

advertisement

For Chi Nan STUDYING SOUTHEAST ASIA IN A GLOBALISED WORLD Anthony Reid Asia Research Institute National University of Singapore My theme today is not simply the study of Southeast Asia, but the broader agenda of which it is part, of seeking to understand the world we live in, in all its diversity. The acceleration that has been given to processes of global integration by the electronic revolution, by the destruction of Cold War boundaries, and by the massive movement of people as well as goods and ideas, is changing the nature of this enterprise. We need to reflect on how this should also change the way we study and teach, and more fundamentally how we think about difference. Is (Southeast) Asian Studies as a discipline in trouble? Everywhere the study of particular languages and cultures is influenced by changing perceptions of where the strength is – the job market, economic growth, the sense of threat, the application of government priority funding, and one hopes also the sheer excitement of studying a civilization not our own, but perceived to be glamorous, deep or challenging. The most carefully watched changes in Area Studies trends have been in the United States, partly because it is a trend-obsessed society where things do change quickly, partly because the American “model” of how to do area studies has been widely admired and rather less widely emulated elsewhere. The basis for this model I now understand better having spent three years battling within it. With a relatively small amount of Federal money, the Federal Department of Education makes universities compete every three years for the status of National Resource Centers in SE Asian Studies, or East Asian Studies, and the other 5 areas into which the non-North American World is divided. Because this status is valuable in impressing Deans, attracting other kinds of funding and attracting the graduate students who make the whole system work, American universities compete to have exemplary area studies centers with all the requisite languages. This 1 explains why the US, but only the US, has numerous Southeast Asia Centers, all more or less identical in their function and structure. Other ways of dividing the world which might be useful but do not fit this model, including tropical studies, Islamic Studies, Buddhist studies or Austronesian Studies, are remarkably rare in the US. The Cold War, and more particularly the hot wars in Indo-China, did increase the amount of funding Washington gave to SE Asian Studies through the 1960s and ‘70s, and somewhat decrease it thereafter. The end of the Cold War also coincided with a tilt against dividing the world in this area studies way in some foundations and particularly the SSRC. South and Southeast Asian Studies were particularly hit by these factors because they were not prominent in US strategic thinking after the end of the Vietnam war, but also lacked the domestic lobbies for them as in the case of Africa and Latin America. These relatively underfunded areas of South, Southeast and West Asia have been the beneficiaries of increased funding from Washington since September 11, 2001, though at the considerable cost of a perceived politicization of the funding. These lurches in US strategic thinking get more attention than they deserve as the key to what is happening to Asian Studies. Even with the small world of the US, a more important factor in sustaining and improving the study of Southeast Asia, in my view, is the diaspora factor, the Asianising of America. The Asian immigration of the past 30 years has been more influential than earlier migrations in affecting University syllabuses, because Asian migrants have been regionally concentrated (11% of California in 2000, though less than 4% nationally); they have overachieved in education; and they have been more interested in cultural maintenance than earlier generations of migrants. At UCLA, where I taught for three years, Asians represented under 9% of undergraduates in 1973, 17% in 1983, 27.8% in 1990, 34.5% in 1995 and 38% in 1999, and these figures are roughly replicated in the whole vast California state system. I reckoned about 15% of the UCLA student body had some Southeast Asian background, among whom the largest groups were VietnameseAmericans (4%), Filipino-Americans (5%), and those classifying as Chinese whose roots were in Southeast Asia (about 4%, I guessed). These provided the real basis for 2 Southeast Asian Studies at UCLA, filling to overflowing language classes in Vietnamese and Tagalog, and history classes touching on these countries, Thailand or Cambodia. More generally, Asian-American students create a demand for more balanced curricula and the teaching of Asian Languages, and currently furnish many of the most exciting graduate students interested in a broader agenda than the politics and anthropology of past generations.1 In Europe, Japan and Australia, there was no such mechanism to encourage uniformity in the way the study of Asia was structured, and so the picture is extremely diverse – healthily so, I believe. Some of the most important institutions specializing in Asia are more than a century old, resulting from long-forgotten initiatives from governments in need of more language and other expertise. The oldest is the Ecole des Langues Orientales Vivantes (LanguesO, 1795 – now INALCO) in Paris, containing at least in name the world’s oldest chair in a Southeast Asian language, since one of the three chairs established in 1795 was in Persian and Malay (though the Malay side was not filled until the 1830s). In the late 19th century the chairs of Arabic, Malay and Javanese were established at Leiden, while SOAS was established in London under the exigencies of war in 1916. Tokyo University’s Department of Oriental History and the Tokyo School of Foreign Languages (1899, now TUFS) both go back as far as the Meiji era, and the Toyo Bunko to 1924, all providing an institutional base for Southeast Asian interests to be added from the 1930s onward, on a basis which was much closer to European orientalism than to American social science. A Japanese version of self-conscious "Area Studies"(chiiki kenkyu), including Southeast Asian Studies, developed only after the war, first in the Institute for Developing Economies (Ajiken, 1957), and later in the Centre for Southeast Asian Studies at Kyoto, which began in 1963 with some American (Ford Foundation) input, but which soon evolved in a similar direction to the Ajiken. The following year the Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa (ILCAA, 1964) was established next to the 1 This phenomenon is much more fully explored in Southeast Asian Studies for a Globalising Age, ed Anthony Reid (Tempe: Arizona State University Centre for Southeast asian Studies, forthcoming 2004). 3 TUFS campus. The Japanese model emphasized total immersion in the field, with a minimum of theoretical disciplinary alignment by western standards. The emphasis was interdisciplinary and often collective, with a rather rich organisational life of teams and study cells tackling each country or area. The approach has produced some wonderful and inspiring results, known to non-Japanese readers like myself through the Ishii-edited exploration of rice agriculture systems in Thailand, Sakurai's similar work on Vietnamese agricultural history, Suehiro's meticulous study of Thailand's corporations, and the work of Momoki and numerous others on early Ming-period history. Because it resists the selfabsorbed theoretical trendiness which drives American social science, this tradition is particularly refreshing for westerners. On the other hand, as Suehiro has observed in a critical review of the subject, the benefits of this approach still "leave us in a quandary in teaching students. What can we say besides 'Go there and learn'?"2 In Australia the government intervened only after World War II to create two institutions in Canberra which cut the cloth differently from US Area Studies, namely what eventually became the Research School of Pacific & Asian Studies (1947) and the Faculty of Asian Studies (1950). The very diversity and anachronism of some of these institutions make them annoyingly resistant to trends, but at the same time more enduring in the long term. Finally, the most encouraging trend of all is in Southeast Asia, where Southeast Asian Studies has been gaining strength in the past decade, the same period it was questioned in the US. The study of Thai, Vietnamese and Indonesian have been unprecedentedly popular in the last decade, in Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand, and in since 1995 the Southeast Asian Studies Regional Exchange Program (SEASREP) has been able to encourage this kind of exchange. I want to return to the issue of Southeast Asian Studies in Southeast Asia below, since I think it is central to the naturalization of the discipline in the post-colonial era. Let me say at this point that some of the progress is part of the globalising process, to the extent that Southeast Asian Studies takes place in English. 2 SUEHIRO Akira, "Bodies of Knowledge: How Thinktanks have affected Japan's Postwar Research on Asia," Social Science Japan February 1997. 4 Good students no longer face a choice between studying another Asian language or a European language. The Asian study is in addition to English and is often pursued through English, which has become the lingua franca of the region to a degree unprecedented in any previous era. Intellectual Trends: From “Orientalism” to “Postcoloniality” A somewhat deeper layer of scepticism about Asian Studies was generated by the attack of Edward Said on what he characterized, and essentialised, as “Orientalism”, the urge to categorise and control an exotic or threatening “other”, involving in his eyes romanticism, reductionism, and the prioritizing of canonical texts.3 This struck many chords, especially with students in his own field of European literatures, as a new way of tackling hegemonic knowledge. Said, Gayatri Spivak and others have defined a new field of post-colonial studies, which have in many ways reinvigorated comparative literature and its uses in Asia, and given new legitimacy to the study of hybrid popular cultures everywhere. There was unfortunately also a Sophomoric tendency to use Said’s critique for purposes for which it was not intended, to discredit the serious study of difficult languages and texts " in implicit contrast to the disciplinary jargon of much contemporary social science. This type of reaction is fortunately less common today, not least because of the steps towards Asianising the study of Asia, as well as the increasing normalization and everyday-ness of cultural borrowing which globalization entails. And since one of Said’s measures of the power distortion involved in Orientalism was his claim that “no one is likely to imagine a field symmetrical to it called Occidentalism”,4 it must be significant that Southeast Asia’s first Institute of Occidental Studies was established in 2003 at the Malaysian National University, UKM. 3 Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Random Books, 1979), pp.300-01 and passim. Said, Orientalism, p.50. “Western Studies” has in fact had a long history in Asia, especially in Japan as seiyo-shi, though only recently has the vast industry of studying the west outside it begun to be called Occidentalism in English, in part under the influence of Said; e.g. James Carrier (ed.), Occidentalism: Images of the West (Oxford: Clarendon, 1995). 4 5 The fact that more and more Asian scholars do write perceptively about other Asian countries in English makes internationalisation not just an aspiration but a process. There remain appalling inequalities of access to what we tend too glibly to call "international" discourse, and of power within it. But this discourse, in Asian Studies more obviously and necessarily than in any other discipline, is at least plural, and must ever strive to be more so. The Unification of knowledge is perhaps a more fundamental threat to Area Studies as it has been practiced. . The first Southeast Asianists had no choice but to immerse themselves in the country in question for half a lifetime. This applies of course to European pioneers like Alexandre de Rhodes or Francois Valentijn, but hardly less so in the early nineteenth century for Raffles, Crawfurd and Pallegoix. The object of study was remote, exotic, opaque and extremely different, and the people who had “been there” over a long period had the authority to interpret it. Indigenous voices who could represent themselves directly to an audience reading European languages were virtually absent, and the 19th Century pioneers who did speak to the West stood out precisely by their exotic rarity; - Raden Saleh of Java, Jose Rizal of the Philippines, King Chulalongkorn of Siam. The long process of integration since the sixteenth century has been incremental, with the twentieth century ‘s technologies of air travel, telephone, radio, TV and finally the internet increasing the pace of change to an undreamt-of degree. But in that centurieslong process, the last fourteen years since the end of the Cold War have been truly exceptional in the rapidity with which physical and cultural distance has contracted. There has never been a global lingua franca as effective as English has now become. In my younger days we envied the international journalists their access to Reuters tickertape news coming through the cable, and we had no doubt that a good area studies operation had to have a mountain of national and local newspapers, acquired with great difficulty and usually arriving if at all a few months late. There was no real alternative to being there. Today, as we have all experienced, the one place to be most out of touch with 6 Indonesian political and cultural debates seems to be in an Indonesian village with no warnet (internet café). From our offices anywhere in the world we can access excellent Japanese, Indonesian or Thai newspapers in English and the vernacular, as well as a myriad of clipping agencies for our particular interest. Diasporas have been a factor in mediating cultural knowledge for millennia, but they too play a different role in this post-cold-war era. Firstly the number of Asian migrants has expanded extremely rapidly to some of the wealthiest countries. The end of discrimination in the US, Canada, Australia, NZ and to some extent Japan allowed Asian migrants to rise very quickly to become the largest category in all these countries. The Asian share of US “legal immigration” expanded from 7% in 1965 to 42% in the 1980s, ensuring that Asians are now the most rapidly-expanding sector of the US population.5 In Australia Asian migrants have exceeded European (including UK) since 1984.6 Secondly the coincidence of this vast flow of migrants with the rise of the internet and satellite TV has made it possible to retain and promote one’s culture, both by watching Korean TV in California and by developing web sites for one’s own identity, now more easily seen as a worldwide portable category. I did a little check on some identities that might once have been thought a bit esoteric as talking points with non-Asianist colleagues: Ryukyu turned up194,000 sites, Minangkabau 35,000, Ilocano 21,400 and Lao, even when qualified as Lao culture, got all of 227,000. For all of these and any other you can mention there are multiple home sites, many of them maintained in English by diasporic subjects. Need we be surprised that journalists or officials who thirty years ago might have started a quest for information by ringing their friendly academic Asianist will now go to the web? These changes look like massive gains for the universalists, who see no need to adopt different approaches for different cultural groups. A further factor in their favour has been the statistical unification of (most of) the world in the form of believable and 5 Paul Ong, Edna Bonacich and Lucie Cheng (eds.), The New Asian Immigration in Los Angeles and Global Restructuring (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1994), pp.45-52. 6 Stephen Castles, ‘The “New” Migration and Australian Immigration Policy,’ in Australia: The Dynamics of Migration and Settlement, ed. Christine Inglis et al (Singapore: ISEAS, 1992), pp.58-9. 7 uniformly coded data assembled by the United Nations and the World Bank. Fukuyama’s “end of history’, might better have been glossed as ‘the triumph of the economic’. In the post cold war era the only kind of competition more important than the World Cup is that for GNP per capita, FDI rates, and gini coefficients. We read each week in the back pages of the Economist or the Far Eastern Economic Review how our team is doing by these indices. No longer is the competition about selling the world on the greater moral rectitude of one’s government, its revolutionary credentials or popular support, and lying with statistics to support the case. Sukarno and Mao could project themselves internationally with some success as virtuous liberators while inflicting great economic pain on their peoples, but in modern conditions the Burmese junta and Robert Mugabe have notably failed to pull this off. It is now possible to compare hundreds of variables for scores of countries without leaving your lap-top, let alone your language. At least in Economics and Political Science in-depth cultural knowledge of one country has been rapidly marginalized, to the point of being almost a disadvantage in getting a job in a US university. In many other fields of applied science, public health, demography, psychology this has long been the case. At this level, making the case for Asian Studies has got a lot harder. As against this, however, I believe the “cultural turn” represented in the academy by much post-Marxist and post-structuralist theorizing, and in the real world of Asia by a new emphasis on (“glocalized”) religious and cultural identities as distinct from secular nationalist ones, represent an even more important surge in the opposite direction. Much has changed since the Southeast Asian “other” presented itself to my generation as radical nationalism, busily marginalizing “primordial” identities. Since the “cultural turn”, the closest equivalent of that Marxisant nationalism is a narrowly scriptural Islam (or Salafi-ism), also engaged in opposing the global hegemon and in rejecting tradition and the local in the name of an essentialising dream of a new millennium – though one much harder for most of us to understand. Alongside it are a host of other assertions of identity in ethnic, religious, reformist and popular culture terms, dazzlingly diverse and dynamic. 8 In short, this cultural turn suggests that the demand for Asianists who understand the culturally specific is greater than ever, despite or rather because of the collisions to which globalisation gives rise. But keeping pace with the change is a job for the young; the “other” we learn to understand is already a recent construct, and new pressures will surely create new challenges to understanding before we have mastered the first. All that is solid has long since melted into air, and the challenge of understanding the newly constructed identities requires even more nimble minds than did the canon of great texts. SE Asian Studies in SE Asia There has indeed been a long-term tendency for outsiders to be more loquacious about the region than its own inhabitants – relatively sparse until the nineteenth century. A modern world-historian complains “It is remarkable that a region that for so long occupied the position of cross-waterway of the world should have had so little to say for itself”.7 Like all multi-ethnic and multi-polar regional systems, it also seemed more coherent to outsiders than to stay-at-home locals. For many centuries the exceptionally literate societies of China and Japan produced reports and surveys of the kingdoms of the “southern seas” (Nanyang, Nampo). Even earlier Indian epic literature was aware of a gold-rich region of strange customs called Suwarnadvipa. As the Indian Ocean became a Muslim lake in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, “lands below the winds” (tanah dibawah angin in Malay) became the way Southeast Asia was distinguished (from India, the Middle East, and later Europe) in the ports of the region itself, and for Malay, Arab and Persian speakers more widely. Despite the borrowing of scripts, myths and cosmologies from the Indian sub-continent, the earliest Southeast Asian texts are more conscious of their neighbouring Southeast Asian states than of Indian exemplars. The Desawarnana (Nagarakertagama) composed in the Javanese kingdom of Majapahit in 1365, for example, lists almost a hundred 7 Janet Abu-Lughod, Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250-1350 (New York, Oxford University Press1989), pp.296-7. 9 islands and polities (as far as the Malayan peninsula and New Guinea) held to be tributary to Majapahit, but also Siam, Cambodia, Champa and Vietnam (Yawana) on the Southeast Asian mainland which are friends or trading partners.8 Cambodian and Cham inscriptions confirm the interactions and royal marriages between these regions and Java. During the period of intense Chinese-Southeast Asia official interaction before about 1450, the envoys of north Sumatran ports, Melaka, Java, Siam and Champa often travelled together to the Chinese capital and even represented more than one of the Southeast Asian states. The first serious surveys of the region as a whole that have come down to us, however, derive from the outsiders who took up residence there for longer or shorter periods. Chinese writers such as Chau Ju-kua in the thirteenth century, Wang Da-yuan in the fourteenth or Ma Huan in the fifteenth typically set out to convey for Chinese readers the wonders of “the islands and their barbarians”, and the success of the Middle Kingdom “in civilizing the barbarians of the south and east”.9 While not limited to Southeast Asia in a modern sense, they devoted most of their pages to it, and gave the earliest overall picture of a fabulous and varied region. The first European survey with the same degree of immediacy and comprehensiveness was that of Tomé Pires, writer and accountant of the Portuguese settlement at Melaka between 1512 and 1515. There he perceived how “Melaka is surrounded and lies in the middle, and the trade and commerce between the different nations for a thousand leagues on every hand must come to Melaka”.10 Like many residents of that Malacca Straits region to follow him, he recognised the region in its commercial links, and devoted the larger and more valuable half of his Suma Oriental to what he sometimes called “High India on the other side of the Ganges”, in contrast to the first and second (or middle) Indias. The first native of Southeast Asia to write about the region in a European language was Godinho de Eredia, born in Melaka in 1563 of an 8 Stuart Robson (trans.), Desawarnana (Nagarakrtagama), by Mpu Prapanca (Leiden: KITLV Press, 1995), p.34, also p.85 where some Indian states are also noted. 9 These quotations, the first being the title of Wang Da-yuan’s book, are from Ma Huan, Ying-yai Shenglan: The Overall Survey of the Ocean’s Shores, trans. J.G. Mills (Cambridge: Hakluyt Society, 1970), pp.69 and 72. 10 The Suma Oriental of Tomé Pires, ed. Armando Cortesão (London: Hakluyt Society, 1944), p.286. 10 aristocratic Bugis mother and Portuguese father, simply called the region ‘Meridional’ or southern, India.11 The centrality that Melaka had for Southeast Asian trade in the late fifteenth century was in due course almost replicated by Banten and Ayutthaya (around1600), Batavia (in the century 1650-1750) and by Bangkok at least for Chinese traders in the period 1780-1820. But it was Singapore, established as a free port in 1819, which most fully emulated and expanded the role that Melaka had briefly held as collecting entrepot on the strategic Malacca Straits for all the goods of the Southeast Asian maritime region. It is therefore not surprising that Singapore produced its equivalents of Tomé Pires, long-time residents who perceived the coherence of the Southeast Asian region through its trade. Singapore journalist J.H. Moor in 1837 produced perhaps the first regional study to be published in the region in English, drawing heavily on the accounts of different countries in the newspapers he had edited.12 This in turn influenced the more ambitious Descriptive Dictionary of John Crawfurd (1856), which covered all parts of what we today think of as Southeast Asia except Burma and the landlocked far north.13. Crawfurd had prepared for writing it with three years in Pinang (1808-11), five in Java (1811-16), three in Singapore (1823-26) and missions to Siam, Vietnam and Burma. Locally printed journals in English devoted to the same terrain began with the Indo-Chinese Gleaner, published quarterly in Melaka by the London Missionary Society (LMS) in 1817-22. Even more valuable was the Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia, of which J.R. Logan brought out twelve volumes in Singapore between 1847 and 1862. It is now a familiar story how high colonialism constructed the boundaries of Southeast Asia’s eleven (if we include East Timor) nation states, which were in turn sacralised by both colonial and anti-colonial nationalisms. The twentieth century was an age of passionate nationalism, in general unsympathetic to transnational enterprises such as regional studies. Eredia’s Description of Malaca, Meridional India, and Cathay, trans. J.V. Mills (Kuala Lumpur: MBRAS, 1997). 12 J.H. Moor, Notices of the Indian Archipelago and Adjacent Countries (Singapore: 1837). 11 11 Having conceded that, we should not forget the way even prominent anti-colonial nationalists reached out to the region as a source of identity and inspiration. The first of them, the brilliant Spanish-educated, Chinese-Philippine physician José Rizal, was profoundly stimulated by his discovery of a common “Malay” identity (what we would today call Austronesian) in much of the region. Through his correspondence with the Austrian Orientalist Ferdinand Blumentritt he was inspired to begin reading the Dutch authorities of the day on Indonesian ethnology, and to refer to his Filipino identity as “Malay”.14 The University of the Philippines did introduce the teaching of Malay and Austronesian languages in the 1920s, but not so much out of regional solidarity or curiosity as in an attempt to deflect nationalist student pressure for Tagalog.15 The pioneer nationalist who most clearly became a “Southeast Asia scholar” was Nguyen Van Hoang. He taught Vietnamese at the Ecole des Langues Orientales in Paris in the 1920s and ‘30s, extended his studies to Leiden and London and learned enough Dutch and English to be able to reconceptualise the region as an ethnographic whole. His pathbreaking investigation of common patterns of house-building in the region was probably the first by an ethnically Southeast Asian author to use the term “Southeast Asia” in its title.16 ASEAN, formed in 1967 and finally incorporating the last of the ten states of the region (Cambodia) in 1998, was by no means the first attempt to form a regional grouping. Even at a time before the spread of English among elites, when nationalist leaders had difficulty finding a common language to communicate in, Comintern politicians like Ho Chi Minh, the Chinese-Vietnamese double agent Lai Tek, and the Indonesian revolutionary Tan Malaka were constructing pan-regional underground networks. Tan 13 John Crawfurd, Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands and Adjacent Countries. London: Bradbury & Evans, 1856. 14 The Rizal-Blumentritt Correspondence, Vol.II (Manila: José Rizal Centennial Commission, 1961), pp.12, 349-50, 500-02. 15 Barbara S. Gaerlan, "The Politics and Pedagogy of Language Use at the University of the Philippines: The History of English as the Medium of Instruction and the Challenge Mounted by Filipino," Ph.D. dissertation, UCLA, 1998, chapters 2 and 3. 12 Malaka began writing about a “Malay” federation of the Philippines, Malaya and Indonesia in 1926. By 1942, after he had split from the Comintern, his dreams had expanded to a Southeast Asian federation he called “Aslia”, within a 1500-mile radius from a focal point in Singapore.17 In the short interval between the Japanese surrender in 1945 and the onset of the Cold War in 1948 there was another burst of Southeast Asian solidarity on the nationalist left, though the short-lived Southeast Asian League based in Bangkok in 1947 was beset with problems from the start. Vietnamese and Burmese leaderships were particularly enthusiastic. Burma’s Aung San pressed in 1946 for “something like the United States of Indo-China comprising French Indo-China, Thailand, Malaya, Indonesia and our country”.18 The most natural places from which to conceive the coherence of Southeast Asia and the need for its study as a region were the entrepots clustered around the Straits of Malacca. But educational and scholarly institutions were relatively slow to develop in British Malaya, and it was not until the 1950s that Southeast Asian Studies began systematically there. Before World War, in the colonial era proper, the lead was taken by Rangoon and Hanoi. Although in many ways French rule severed economic and political links between the Indo-Chinese societies and their neighbours, French scholarship was another story. The Khmer monuments of Angkor, and to a lesser degree the Cham monuments in Central Vietnam, stirred the interest of French and Vietnamese scholars and led them to look across colonial boundaries. The major project of the Ecole Française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO), established in Saigon in 1898 but subsequently headquartered in Hanoi, was the restoration and analysis of Angkor, systematically commenced in 1907. This enterprise led them to seek connections in Bangkok (where Coedès was Director of the Royal Nguyen Van Hoang, Introduction a l’étude de l’habitation sur pilotis dans l’Asie du sud-est (Paris: Paul Geuthner, 1934). 17 Tan Malaka, From Jail to Jail, trans. Helen Jarvis (Ohio: Ohio University Center for International Studies, 1991), pp. xcvi-xcvii. Anthony Reid, ‘A Saucer Model,’ p.17. 18 Speech to AFPFL 20 January, 1946, in Speeches of Bogyoke Aung San (1945-1947) (Rangoon, 1971), p.36. See also Christopher Goscha, ‘Thailand and the Vietnamese Resistance Against the French, 18851949’, Unpublished M.A. Thesis, Australian National University, Canberra, 1991, pp. 136-64; Reid, ‘A Saucer Model,’ pp. 17-18. 16 13 Museum for several years), and in Java, where a series of exchanges with Dutch archeologists began in 1929. It was no accident, therefore, that the first demonstration of the integrated early history of Southeast Asia was the work of Coedès at his EFEO headquarters in Hanoi.19 Rangoon University, along with the University of the Philippines where Southeast Asian scholarship was not greatly emphasized, was the leading English-language university of the region before World War II. D.G.E. Hall was its first professor of History, in 192134, and the experience turned him into a Southeast Asianist (having worked previously in Britain on the foreign policy of Charles II). Having discovered on arrival a history syllabus exclusively devoted to Greece, Rome, Britain, Europe and India, he reorganised it as a world history syllabus, including an important field of what he called ‘East Asian History’, with Burma at its center. G.H. Luce was recruited to teach and research this area. Hall himself, however, with his unusual facility in Dutch as well as French, responded sufficiently to what was being written elsewhere in the region to be able to hit the ground running as Britain’s first Professor of Southeast Asian History (at SOAS, London) in 1949, and author of the path-breaking History of South-East Asia (1955)20. Meanwhile his colleague at Rangoon University, the political economist J.S. Furnivall, had begun in the 1930s to work in Indonesia as well as Burma, and to respond to the Institute of Pacific Relations’ commissioning of specifically “Southeast Asian” surveys. 21 The University of Malaya, established in Singapore in 1949, renewed the local sense of Southeast Asian discovery that Rangoon University had initiated. The first generation of professors included E.H.G. Dobby, whose pioneering Southeast Asia preceded the George Coedès, Histoire Ancienne des Etats Hindouisés d’Extrême-Orient (Hanoi, 1944). The second (1948) and third (1964) editions were entitled Les Etats Hindouisés d’Indochine et d’Indonésie, and the English translation of the third edition, The Indianized States of Southeast Asia (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1968). 20 D.G.E. Hall, A History of South-East Asia (London: Macmillan, 1955; later editions 1964, 1968); C.D. Cowan, ‘D.G.E.Hall: A Biographical Sketch,’ in Southeast Asian History and Historiography: Essays presented to D.G.E.Hall, ed.C.D. Cowan and O.W. Wolters (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1976), pp.11-23. 21 J.S. Furnivall, Netherlands India. A Study of a Plural Economy (Cambridge University Press, 1939, reprinted 1967); J.S. Furnivall, Progress and Welfare in South-East Asia (New York: Institute of Pacific Relations, 1940). 19 14 historians in demonstrating the environmental personality of the region – and unlike Hall’s book did not omit the Philippines.22 Among his junior colleagues were Paul Wheatley and Kernial Singh Sandhu, both of whom went on to play major roles in defining the sub-discipline. Ken Tregonning, professor of history at the University of Malaya from 1959, sought to ride the mood of Singapore as a regional centre through the next turbulent decade. A crucial step was the first international conference of Southeast Asian historians he organized in January 1961, attended by a hundred delegates predominately from the region. This was the impetus which gave rise to the International Association of Historians of Asia, which has held sixteen subsequent conferences in the region. Tregonning also launched the Journal of Southeast Asian History from his Department in the same year, publishing in its second issue the seminal article by John Smail which had been written for the January conference, and quickly became core reading in Southeast Asian history courses across the world.23 These regional developments were critical for the development of the study of Southeast Asia in English. There were also initiatives in Singapore expressed in Chinese which demonstrated a broader base for regional study, even if not one that flourished in the longer run. Even throughout the divisive high colonial era Chinese mercantile networks had been aware of the region’s interrelatedness as had few others. These Singaporecentered commercial networks led not unnaturally to Singapore-centered educational networks. Even the British sponsored Raffles College, ancestor of the University of Malaya in the 1920s, obtained its largest individual donation from an Indonesian Chinese, the sugar magnate Oei Tiong Ham. In the 1940s the bilingual journal of the Singapore Nanyang Xuehui (South Seas Society) was one of the first since the nineteenth century to take Southeast Asia as its scope. In 1956 the Chinese (especially Hokkien) networks of the region cooperated to launch Nanyang University, which aspired to be a regional university in the Chinese Medium. Much earlier than its English-language opposite 22 23 E.H.G. Dobby, Southeast Asia (London: University of London Press, 1950 – 7th edition 1960) John Smail, ‘An Autochthonous History of Southeast Asia’, JSEAH I, no.2 (1961). 15 number in Singapore it also aspired to teach regional languages, Bahasa Indonesia being among the offerings from the beginning. With the independence of Malaya in 1957, the University of Malaya split into two campuses, and universities proliferated in both Malaysia and Singapore from the 1970s. At virtually all the universities which taught social sciences and humanities the inheritance of the University of Malaya was followed with courses routinely offered in Southeast Asian history, geography and politics. At the major research universities there were specialists on Indonesia, but also on Thailand, Vietnam, Burma or the Philippines. Since the 1960s the highest enrolments anywhere in the world in courses relating explicitly to Southeast Asia have probably been at these universities in Singapore and Malaysia. Moreover many of those who learned in this system how to teach courses across the whole of Southeast Asia, including myself, went on to play roles elsewhere in substantiating the region as a coherent field of study.24 Facilities for graduate study, research, and language training were slower to develop, since in this as in all fields it long seemed more cost-effective for graduate students to go overseas. Research institutes and think tanks devoted to Southeast Asia developed earlier, in Hanoi and Singapore. A Department of Southeast Asian Studies was established in 1973 within the Vietnam Social Sciences Committee primarily concerned with Laos and Cambodia. Gradually it evolved into the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies within the Vietnam Academy of Social Science, to deal also with the countries of ASEAN. Vietnam’s entry into ASEAN in 1996 provided the justification for the Institute’s glossy English-language journal – Review of Southeast Asian Studies.25 Much more important a regional player was the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS) which Singapore established in 1968. Its founders sought to make it internationally and regionally respectable, by hiring leading international Southeast Anthony Reid, ‘A Saucer Model of Southeast Asian Identity,’ p. 9. Pham Duc Duong, ‘Southeast Asian Studies and the Review “South East Asia Studies”’, in Toward the Promotion of Southeast Asian Studies in Southeast Asia, ed. Taufik Abdullah and Yekti Maunati (Jakarta: Indonesian Institute of Sciences, 1994), pp. 238-55. 24 25 16 Asianists (Harry Benda, John Legge and Josef Silverstein) as its initial short-term directors (to be followed by long-term Kernial Singh Sandhu), and by consciously wooing prominent scholars from each major Southeast Asian country. had become By the 1980s ISEAS was one of the world’s leading research and publishing centers for Southeast Asian Studies, though without any teaching role. That expensive role of training students in Southeast Asian languages and cultures began slowly in Malaysia in the 1970s. Bahasa Indonesia courses were felt unnecessary because of the prominence of Malay, but Thai was introduced as an undergraduate subject at the University of Malaya in 1976, Tagalog in 1980, Burmese in 1984 and Vietnamese in 1993. These formed the core of a Southeast Asia Program from 1976, and a full Department of Southeast Asian Studies from 1989.26 At the National University of Singapore (NUS) the undergraduate program in Southeast Asian Studies was inaugurated in 1991, with Bahasa Indonesia introduced in 1992, Vietnamese in 1995 and Thai in 1998. Despite this late start the NUS program in 2001 had three full-time lecturers each in Thai and Vietnamese, and these language programs can already claim to be among the largest in the world. The 2001 Directory of Southeast Asianists at NUS lists 107 faculty, including (with overlaps) 25 specialising on Thailand, 20 on the Philippines, 34 on Indonesia and 13 on Vietnam.27 In the late 1990s this type of program was extended to Thailand, where Vietnamese and Indonesian courses proved popular. Conclusion: Alterity and Universalism In closing let me try to peel off some of the specific contextual factors that effect Southeast Asian Studies, and draw attention to a more fundamental tension in us all. In some earlier writing I have referred to this as a tension between universalism and alterity.28 Universalism is the generous idea that all humans on this planet we share are Shaharil Thalib, ‘The Department of Southeast Asian Studies, University of Malaya, 1976-1993,’ in Toward the Promotion of Southeast Asian Studies, pp.39-86 27 Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, The National University of Singapore, Directory of Southeast Asianists, January, 2001. 28 Anthony Reid, Introduction’, in Southeast Asian Studies for a Globalized Era, ed Anthony Reid (Tempe, AZ: Arizona State University Center for SE Asian Studies, forthcoming 2004). 26 17 governed by similar desires and constraints, and that the most obvious divisions between them, whether of language, culture, race, wealth or education, are predominately social constructs which people of learning and goodwill should transcend. This is a fundamental principle of science, in its quest for universal understanding of our bodies, our brains, and our environments. Its strength is its aspiration to a genuinely global dialogue in neutral language; its ability to puncture ethnocentric political cant about uniqueness, virtue or victimhood with empirical evidence of our universally flawed natures. Its weakness, especially as it is extended into the social and human sciences, is its tendency to confuse hegemonic knowledge with genuinely universal knowledge; to deny autonomy to the other; to read the quantifiable and the comparative as the objective; and to marginalize or trivialize that which it cannot comprehend. Alterity is the opposite principal, which rejoices in difference and seeks to understand and explain it. Frequently it is motivated by a discontent with the familiar and the hegemonic; and a desire to relativise these by seeking out other and perhaps better ways of organizing society. This principle has been most at home in disciplines such as literature, history and anthropology, and of course preeminently in Asian Studies. Its strength is its insistence on understanding otherness in its own terms, giving voice to the voiceless or underappreciated, and showing sensitivity to cultural diversity. Its weakness is its tendency to essentialize otherness in the process of explicating it. Pendulums may swing, but the tension between these two types of understanding is not going to go away. We need both, and more than ever in a globalising world. 18