MS Word

advertisement

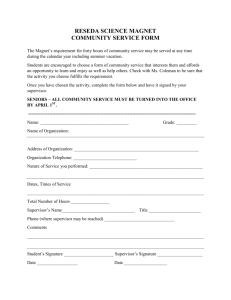

Using academic-corporate research partnerships as learning events in computing, illustrated by a case study. M. Ruth de Villiers University of South Africa dvillmr@unisa.ac.za Abstract This paper overviews conceptual models of scenarios where academics conduct research relating to real-world software artefacts. A methodology is proposed for using academic-corporate research partnerships as learning experiences, whereby students in disciplines such as computing and information technology can contribute to private sector organizations, yet synergistically use the experience to benefit their formal studies. The methods can reconcile different, but not necessarily conflicting, objectives and are il1ustrated by a case study relating to an evaluation by a learner-educator team of a multimedia application built by a commercial software developer. Keywords: Postgraduate practical work / learning experiences, academic-corporate research partnerships, collaborative work, pilot projects, human-computer interaction, usability evaluation 1 Introduction This paper proposes a methodology for using academic-corporate research partnerships as learning experiences, whereby post graduate students in disciplines such as computing and information technology can contribute to private sector organizations, yet synergistically use the experience to benefit their formal studies. Practical realworld projects are increasingly becoming an intrinsic part of formal study, as tertiary institutions require integrated assessment [4], which requires learners to combine knowledge and skills, demonstrating applied competencies by integrating foundational, practical, and reflexive competence in a variety of contexts. BSc Honours students in the Department of Computer Science and Information Systems at Unisa are required to do project modules [3], double-module practical projects. Students choose from options in several focus areas, most involving a research component. Several options require software development and/or evaluation. Project modules also fulfil the purposes of integrated assessment, in that they entail a holistic project-type deliverable near the end of formal degree studies and some of the focus areas integrate more than one discipline [3]. Section 2 sets out conceptual models of certain research scenarios, including cases which bridge academia and the corporate world. The models indicate patterns and stakeholders in some of the situations where academics and/or postgraduate students conduct research relating to real-world software artefacts. In Section 3 a methodology is suggested to generate work-products that can reconcile different, but not necessarily conflicting, objectives in a multi-stakeholder academic-corporate 'boardroom dance'. The model and methods are briefly illustrated in Section 4 by a case study of an HCI usability study by a learner-educator team working closely with their corporate ‘client’, who developed a multi-media application which the academics are evaluating. 2. Models for real-world projects To set the context, this section overviews stakeholders and patterns in some of the common situations where academics and/or postgraduate students conduct real-world research relating to software artefacts, as opposed to hypothetical academic efforts. The conceptual models under the spotlight relate particularly to software development and/or evaluation. We mention some basic forms, culminating in a description of a multistakeholder variant. After describing each model and its stakeholders, we indicate to whom the researchers are accountable in each variant, and what outputs emanate. The first form involves an educator/team of educators undertaking research developing or investigating the efficacy of software artefacts / learning programs in their own academic organization, using their learnerpopulations as subjects. Figure 1 shows the simple AA Model representing this scenario. In developing and/or evaluating a software system or tool, of which students are the end-users, the academic researcher is accountable to his/her academic institution. A publication is envisaged as output, and usually a separate report to management or to the section where the artefact originated or is used. academic organisation academics A r t e f a c t students as end-users Figure 1: AA Research Model (Acad_AcadOrg) An extension of this model (Figure 2 - AAA Model) is encountered when one of the academics uses the research as a learning experience towards postgraduate qualifications. In this case, another academic (although possibly a co-researcher) is in the situation as supervisor. Accountability is primarily to the supervisor and academic department, and the major deliverable evolves as the learner writes up the research for a project, minidissertation, half-dissertation or full dissertation, though there may also be a report as in the AA Model. academic organisation academic supervisor academic post grad. A r t e f a c t students as end-users Figure 2: AAA Research Model (Acad_AcadStud_AcadOrg) The next step is to look at scenarios where the main beneficiary is an external organization in the public/private sector. Figure 3, the AEE Model shows stakeholders in the case where an employee of some institution takes a project or software development he/she is doing in the workplace, and synergistically uses it for academic purposes. As in Figure 2, we have a postgraduate student and a supervisor, the major difference being that the student is accountable to his/her employer for the real-world value of the work, and separately accountable to the academic institution for its worth towards a qualification. Outputs are documents/artefacts in various forms and formats for the employer-organization, and a further document/s generated towards degree qualifications. external organisation A r t e f a c t academic supervisor external post grad. external end-users workplace Figure 3: AEE Research Model (Acad_ExtStud_ExtOrg) Furthermore, as budgets are pruned and explicit research divisions whittled down, the private and public sectors are increasingly turning directly to academic institutions for research input [1]. Thus contract research - which may be basic, applied or ad hoc research, and which may or may not entail development - is undertaken by academic teams or individuals. Figure 4, the AE Model, demonstrates the interrelationships in the simplest of this type of scenario. The academics are accountable to the contracting organization or state body, and must generate reports and produce feedback for them. Research outputs will likely also result, provided publication does not breech confidentiality external organisation A r t e f a c t academics Figure 4 external end-users AE Research Model (Acad_ExtOrg) A variant occurs when the model of Figure 4 is extended by one or more parties using it in the pursuit of further qualifications, leading to the ASE Model in Figure 5. This project differs from other scenarios where students undertake real-world projects (Figures 2 and 3) in that the learner is not doing the work in his/her own workplace. This scenario is the particular focus of this paper, the rest of which describes an approach suggesting one possible methodology for situations where research is done jointly by a supervisor and a postgraduate student with the dual aims of: i. providing a corporate institution with usable information or a software artefact, and ii. generating an output deliverable which can be used by the student for academic credits. These aims may diverge, in that corporate requirements are focused on commercial market-related interests viewing theoretical aspects as of lesser worth, whereas academia requires sound theoretical foundations and methodological rigour from postgraduate students. Although a 'corporate client' may, instinctively, require the kind of information that can be seamlessly integrated into a theoretical study, theory must be explicitly incorporated and validity ensured. Furthermore, data collection, data analysis, reporting and publication must conform to appropriate ethical norms; while the write-up must be characterized by sound technical writing and appropriate referencing techniques. external organisation A r t e f a c t academic supervisor post grad. Figure 5 external end-users ASE Research Model (Acad_Stud_ExtOrg) Note also, the specific scenario where the corporate client is a software development house - marketing systems designed and built in-house. They have their own independent clients whom they must convince. The corporation's fundamental interest in the university's findings relates to the degree to which these findings can be used to implement their business plan and reinforce their marketing programme to clients in the commercial market place! This adds to the set of stakeholders, resulting in the ASEI Model of Figure 6. So - with multiple stakeholders and complex dynamics - the boardroom dancing begins and can best be described as a multi-partner barn-dance! external organisation A r t e f a c t academic supervisor post grad. Figure 6 independent client independent end-users ASEI Research Model (Acad_Stud_ExtOrg_IndClient) In such interrelationships, a prime onus on the supervisor is to ensure ethical behaviour and academic integrity, yet s/he is also entailed in implicit accountability for the inherent value of the work-products (findings / artefact) to the commissioning corporation. Depending on the level, capabilities, and role of the postgraduate student, the supervisor may assume a greater or lesser role in the research. Where the student is employed by an external organization - using an existing workplace task as in Figure 3, the student is accountable in an employeeemployer relationship and separately accountable to the university for the academic worth of the work, and the supervisor is not responsible to the organization at all. But where the student is not internal to the commissioning organization (i.e. where educator and postgraduate learner are jointly required by an organization to undertake research), as in the ASE and ASEI Research Models, the supervisor is jointly accountable to ensure worth (regardless of whether or not funding is involved). A further dichotomy arises between the need for the supervisor’s participation in generating products and the separate requirement to assess the learner individually for academic credits. 3. Methodology for a multi-stakeholder scenario Now for a generic methodology – applicable to scenarios such as Models ASE and ASEI in Figures 5 and 6 respectively, particularly where the external organization is a corporate, commercial client. This methodology entails various stages and diverse work-products and is aimed at using academic-corporate research partnerships as learning experiences, whereby postgraduate students can contribute value to organizations, yet synergistically use the work to benefit their formal studies. Products are developed to meet the client’s specification, but should either be directly usable by the academic organization for assessment of the learner’s own work, or should incorporate seamless subdivisions for such purposes. 3.1 Stage 1 - Proposal The supervisor and student hold joint meetings with the corporate client to determine their requirements. The supervisor must consider the situation holistically and suggest the: way forward in broad principles, nature and scope of the pilot project in specific detail. A sound foundation is essential – theory, ethics, and validity cannot be compromised in presentations to, investigations on behalf of, or products for, the client organization. A pragmatic approach is to keep theory crisp and concise in any initial proposal, yet indicating clearly its worth. (Should it become evident that requirements of a corporate client and an academic institution diverge, it must be identified at this stage and a decision made to generate separate work products.) 3.2 Stage 2 - Pilot project Assuming consensus is reached and the proposal is accepted, harmonious music accompanies the barn dance. The pilot study stage is vitally important to the success of the venture. Any product/s generated should be a combined effort by mentor and learner, i.e. the intention is a learning experience for all participants and not assessment of the postgraduate learner. Corporate clients – unused to academic schedules, in business to generate income, and keen on complete results or rapid development of a final product – may ask "What's in this pilot project for me?". Empathy for this viewpoint is essential, combined with clear and convincing explanations as to the following purposes of the pilot project: To test the research methods, instruments and tools: - in the case of an evaluation: the opportunity to conduct a small-scale investigation and to reflect on one's research instruments, so as to refine/extent/enhance them in the full study. - in the situation of software design/development, to build a prototype. To generate, at an early stage, usable and high quality information or artefact/s for the client, e.g. a document/product/ partial software application, prepared jointly by supervisor and student. Inclusion of the supervisor's expertise should add value. Theoretical write-up should be crisp and clear, and fairly basic in initial products. Not to generate academic credits for the learner, except possibly an estimation of his/her ability to engage in the inception of research and/or development. 3.3 Stage 3 Full investigation Based on the results of the pilot study, the software (in the case of design/development) can be adapted and extended towards building a full application. Should the project be evaluation, instruments and techniques such as the evaluation framework, survey questionnaires, questions for semi-structured interviews, tests, usability metrics, observation strategies, heuristic criteria, etc. can now be refined, diversified, and expanded in the full investigation. The methods of applying them can be improved. If necessary, the team can be enlarged with technical- or research assistance. The dual agenda (academic and corporate) may be handled by dividing the dance-floor and generating two separate final products – one as a consultant-style report/artefact to meet the client’s requirements and the other as the student's academic deliverable. Ideally, a single product should be directly usable both by the client organization and by the academic institution for assessment of the learner’s work, but this is not always practical. A third option is incorporate seamless subdivisions for such purposes. Points to note are: Should the dynamics be even more complex, with several students involved in various aspects/components of a project, the final composite product should be compiled and integrated by a facilitator or project leader (who may well be the supervisor/mentor). Although group-assessment, peer-evaluation and self-evaluation play roles in the current culture of cooperative learning, each student must be individually assessed on their personal contribution/s [2]. Different requirements may require exclusive emphases which necessitates separate products (as mentioned previously). For example, the client may require only a software application and user-manual, whereas the academic institution may require details of the development methodology, etc. Where the academic supervisor is co-responsible to the client organization, s/he will make contributions which, though an intrinsic part of the final product, cannot be assessed for the student's academic grading. Each student must be assessed on a partial product comprising her/his personal contribution. A better alternative is once again to separate issues, with the supervisor writing separate modules/chapters or even generating a separate product. Finally the dual-product approach makes provision for cases where a major theoretical component is required for academic purposes, with theory playing a more moderate role in the corporate environment. The lean-and-mean approach to theory suggested for the pilot project must be increased in breadth and in depth for the full project. Soft skills such as teamwork, communication abilities, interpersonal skills, collaborative planning and selfregulation are all required, as the research team fine-tunes each product/document to meet specifications and to ensure that the various stakeholders in the boardroom barn-dance are satisfied. 4. Case study – a usability evaluation: Academics, Boardroom and Miners – dancing together in uncharted waters These mixed metaphors set the scene for a mix-match of multiple stakeholders in which the aim was for everybody to gain something! We briefly mention a venture in which a learner-educator team is undertaking a research partnership with an independent corporate client, which is a software development house. The task in hand is a usability evaluation in the discipline of Human-Computer Interaction, and the system evaluated is a touch-screen, multi-media, speech technology application – a widely-applicable, highly topical health care system – financed and built by the client, and currently being actively marketed in the mining sector. End-users are mainly from the disadvantaged, under-educated sectors of the population. The aim of this section is not to discuss the evaluation in detail, but to illustrate the methods of Section 3. A student came into contact with the corporate organization and together they generated the proposal that s/he should do an independent evaluation of this system - their latest product - in the role of an 'external researcher' and also use the efforts to gain credits towards postgraduate study. Our department asked me, as the student's co-mentor, to communicate with the organization and discuss this dual agenda. It was agreed that I should serve not only in a supervisory capacity, but also as a partner in the actual research - with which the university's name would be associated. Our methodology was generated in this context, with a pressing need to satisfy all stakeholders with usable, timely information, yet also to generate a final document which forms an adequate product for a double-project module. The stages of the evaluation are investigations (qualitative and quantitative) – involving field studies, data collection and analysis; and the products are documents – a pilot project report and a final composite report/s. Survey instruments are questionnaires, observation, and interviews, as well as a separate heuristic evaluation. Triangulation and redundancy help to validate the findings. We are staying in close contact with the client as we plan the overall strategy and the details. For the pilot study, we kept the theory basic and the extent of the investigation fairly lean but incorporating depth. From the literature, we took three classic approaches to usability criteria and, based on this theoretical foundation, compiled pilot questions for our instruments, namely, a survey and semi-structured interviews. The corporation suggested some checklist questions, which meshed well with ours and we integrated them into a single questionnaire. With regard to the observation of end-users interacting with the stand-alone system in a mining environment, we were open-minded as to exactly what we would observe, and what metrics we would record. After all, a main purpose of the pilot study was to reflect upon and refine the methods iteratively. The client suggested an initial investigation using 60 subjects, and a second stage within three months with 120 participants. Our approach was rather to go far smaller in the pilot, but to apply breadth and depth. We requested a small heterogenous sample for a day's fieldwork at a mine. Initially we used the system ourselves, identifying issues and a few minor bugs. Then we observed, interviewed and surveyed seven subjects in depth, recorded results and responses, and obtained rich descriptive data regarding the usability of the system. It also served as an inductive training session for the postgraduate student who had not previously conducted evaluations or usabillity testing. To summarize: Theory: basic; Number of subjects: low; Data elicitation techniques: - broad (range of questions), and - deep (supplementing the structured interview with spontaneous and penetrating questions); Time per subject: up to 50 minutes, completing the survey by consultation, since few subjects could write; Value for student: hands-on, practical training as a real-world co-researcher. The mainly qualitative approach gave us flexibility to explore unanticipated avenues and resulted in notable information. We compiled the findings, which were largely positive, into a jointly-produced document. With the pilot study behind and a report submitted to the corporation a few weeks after our intensive sessions at the mine, we satisfied the immediate corporate need for rapid results and interim usable information regarding their health care system. We had also heuristically identified several bugs to be rectified. For the learner-educator team and the corporate client, the pilot evaluation, particularly the semi-structured interviews, indicated rich new avenues of research and angles of inquiry. In a case where the social sciences and humanities play roles as important as those of technology and software, the initial qualitative, ethnographic data from open questions was more useful than the Likert-scale data from the closed-option surveys. Most important, after a further joint session with the client, we are now into the next stage, in which the aspects of research are being modified. Some issues investigated in the pilot project were shown to be redundant or of little value; others will be investigated in greater depth; further theoretical aspects are being considered, and new metrics are to be included involving an experiment with pre- and post-tests at a site where the system has not yet been used. The process will culminate in two documents – one prepared exclusively by the student (though I will check it rigorously and mark it up regularly) and a separate independent heuristic evaluation from a different perspective, undertaken by myself. The former will also serve as the student's deliverable for year-end module grading. We have requested assistants to extend the team for the full field study lasting a week, since the scale of the survey among 60 respondents and experiment using 10 - 20 participants is beyond the two of us. I, as supervisor, will probably be present on one day only. Discussion Before concluding, it is worthwhile to mention some differences we encountered between corporate and academic cultures and their impact on research: Sphere of research Purpose of research Nature of milieu Results Corporate Academic Market research and independent surveys to validate products (though organizations can do it themselves, independent corroboration is good for the market place!) Competitive; can even be cut-throat Academic qualifications and publication Confidential (will be publicised if expedient) Quick results For publication Cooperative Products Focus Copyright Structured time frames (academic year/semester) Replicable Practice Theory Type of finding Targeted, narrow focus; applied research Rigorous investigation; basic research Time-frames 6. Conclusion This paper set out to introduce conceptual models for certain kinds of research scenarios, as well as a suggested methodology for academic-corporate research partnerships in which at least one of the participants uses the experiences in fulfillment of academic requirements. We described the process we followed and its value, indicating some lessons being learned in this partnership venture. The prime focus of the paper is not the actual usability evaluation mentioned as a case study, but rather the conceptual approach and methodology used to reconcile: i. conflicting objectives due to the different requirements of the corporate client and the academic institution, ii. the participation of the supervisor in developing work products, and iii. the need to assess the learner’s own work for credits. The approach is transferable to other contexts such as the development of software applications, and probably others as well. References [1] De Villiers, M.R. (2002) The dynamics of theory and practice in instructional systems design. Unpublished PhD dissertation. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. [2] Queiros, D. & de Villiers, M.R. (2002) Taking the classroom to the workplace: a case study. In: Proceedings of the 3rd Annual Skills Conference - Skills development in higher education: Forging links. Hatfield, Hertfordshire, UK. [3] University of South Africa (2002a). COS498-X/101/2002: Tutorial letter 101 for PROJECT MODULES. Pretoria: Unisa. [4] University of South Africa (2002b). Assessment Policy. Pretoria: Unisa, July 2002.