2001-04 - Department of Systems and Information Engineering

advertisement

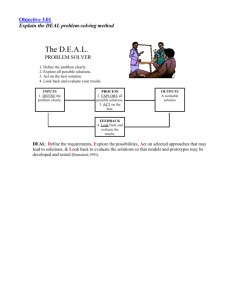

2001 Systems Engineering Capstone Conference • University of Virginia NASA RISK ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT ROADMAP Student Team: Jacob Burns, Jeff Noonan, Laura Kichak, and Beth Van Doren Faculty Advisor: Yacov Y. Haimes Department of Systems Engineering Client Advisors: Jose Caraballo Langley Research Center Hampton, VA j.a.caraballo@larc.nasa.gov KEYWORDS: Risk Filtering, Ranking, and Management Framework (RFRM), Hierarchical Holographic Model (HHM), “Faster Better Cheaper” (FBC), Head-Topic. ABSTRACT Recent mission failures have raised doubts about the effectiveness of NASA’s current risk management procedures. As a result, NASA commissioned the University of Virginia's Center for Risk Management of Engineering Systems, directed by Dr. Yacov Y. Haimes, to develop five-year roadmap that identifies the activities required to meet NASA’s long-term corporate goals. The purpose of the Capstone effort was to locate and analyze different methodologies that could be incorporated into this plan. As with a traditional roadmap, our risk-management roadmap stems from three pieces of information: 1) Where are we now? - What risk management knowledge and practices are currently in place at NASA? 2) Where do we want to go? - What is the level of risk management required to reduce the likelihood of mission failures? 3) How do we get there? - How do we enhance NASA’s knowledge of risk management, and how do we provide the means to implement this knowledge? The methodology discovered that best fits the needs of NASA is an eight-phase approach called the risk filtering, ranking, and management (RFRM) framework. RFRM systematically isolates all critical risks facing a NASA mission. The methodology begins 183 with the identification of several hundred risk scenarios, which are then progressively filtered down to a smaller set of scenarios that are essential for success. These remaining risks generally have a high probability of occurring, with consequences very serious in nature. By generating multiple policy options for each of these scenarios, risk management plans can be developed to reduce the probability of each one’s likelihood of occurrence and minimize the severity of its effects. Recommendation of the optimal alternative in each case is made based on trade-off analyses conducted between associated costs, schedule delays, and effectiveness. Providing NASA with this scientific approach for managing risks will equip them with the tools necessary to safeguard their missions against failure. INTRODUCTION A “Faster, Better, Cheaper,” (FBC) philosophy involves trying to launch more missions at a fraction of the cost. Using this project approach, NASA’s recent missions have experienced many adverse effects. Failures in the past two missions to Mars caused NASA not only to lose millions of dollars and potential scientific return, but also to face the public humiliation associated with disaster (Dickey, 2000). Applying risk assessment and risk management procedures to future projects can prevent further failures from occurring. These processes answer six questions to accomplish their objectives (figure 1). Risk Assessment Risk Management “What can go wrong?” “What can be done?” “What is the likelihood that something will go wrong?” “What are the available options and their associated tradeoffs?” “What are the associated consequences?” “What are the impacts of current decisions to future options?” Fig. 1. The six questions of Risk Assessment and Risk Management (Haimes, 2001) NASA Risk Assessment and Management Roadmap METHODOLOGY The Risk Filtering, Ranking, and Management Framework (RFRM) was created by Yacov Haimes, Stan Kaplan and James Lambert. When applied to a specific mission, the eight phases of the RFRM method guides an effective process that minimizes systemassociated risks. Adoption of these procedural guidelines will allow for the increased reliability of a NASA space project. In Phase I, all of the risk scenarios present in NASA’s organizational structure are identified (Haimes, 2001). These risks form the framework of the Hierarchical Holographic Model (HHM). categories should be discarded. For our analyses, we chose to eliminate the scenarios falling under the moderate and low categories. Fig. 3. Ordinal US Air Force Risk Matrix Fig. 2. Sample Hierarchical Holographic Model The set of risk scenarios is reduced in Phase II using the interests of the current. Scope and temporal domain are two factors that they may consider while thinning the risk set. For example, each NASA center is only concerned with certain technological aspects and time periods of a mission’s implementation and time would be better spent if it concentrates only on risks defined within its defined within this scope. Next, each risk in the narrowed set is qualitatively classified based on probability of occurrence and associated consequences. This step (phase III), called bi-criteria filtering, employs the ordinal version of US Air Force Risk Matrix (Figure 2). The two criteria used to complete the classification are the probability of a risk's occurring and its associated consequences. The probability of risk occurrence is classified as frequent, likely, occasional, seldom or unlikely, while the consequences range from loss of life to no effect. The combination of a scenario’s probability and consequences assign it one of the following severities: Extremely high, High, Moderate, and Low. At this point, it is at the user’s discretion to choose which 184 In Phase IV, each of the remaining scenarios is quantitatively rated on its defensive attributes, such as detectability. Numerous attributes are each assigned a weight and the level of their effects are rated as high, medium, or low, corresponding to scores of five, three, and one. The total scores of all of the scenarios are then calculated and those with a score below a userdefined threshold are filtered out. One important aspect of this phase is that any scenario believed to be crucial to a mission's success can have its categories and weightings altered to generate the necessary score (Haimes, 2001). Phase V is similar to the bi-criteria filtering of phase III in that it also uses the Air Force Risk Matrix, but here cardinal rating is used rather than ordinal classification. Numerical probability ranges minimize any discrepancies in personal judgement among information sources (Haimes, 2001). After phase V, only a few scenarios remain. Phase VI asks, “What can be done to reduce these risks?” This phase consists of an enumeration and analysis of various courses of action, which are assessed for their cost effectiveness (Haimes, 2001). This analysis is performed with the fractile method. Next, the entire system is examined by taking the management policies identified in phase VI into account. In phase VII, the robustness of the plan is evaluated to determine if any risk scenarios may have been missed. This may call for some of the earlier phases to be revisited. Phase VIII is also called operational feedback. This methodology can always be improved upon. An assessment of the cost and time of remedial measures will indicate the effectiveness of the methodology (Haimes, 2001). 2001 Systems Engineering Capstone Conference • University of Virginia APPLICATIONS After generating an HHM for the organization of NASA, mission-specific case studies proceeded to add robustness to the model. Each Capstone Team member chose an FBC-era mission, conducted under NASA’s guidance, on which they ran an RFRM risk assessment. These four missions were the Mars Polar Lander, the Mars Climate Orbiter, the STS-93, and the Cassini Mission. Compiling the common risks remaining after Phase V in the four examinations revealed trends pertinent to an understanding of NASA’s weaknesses. THE MARS CLIMATE ORBITER The Mars Climate Orbiter, a Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) mission, was intended to be the first Martian weather satellite. Orbiting around the planet, the Orbiter’s main tasks were to perform global sounding of the atmospheric and imaging of the planet’s surface, and to provide relay assistance for the Mars Polar Lander. Unfortunately, rather than establishing itself in orbit, the spacecraft crashed into the surface of Mars. The root cause of the mishap was the failure to use metric units in the coding of the trajectory software file, “Small Forces”. The output from this file, SM_Forces, was required by the Mars Surveyor Operations Project (MSOP) Software Interface specification to be in Newton-seconds (metric). Instead the program returned data in poundseconds (English), which caused an offset of 4.45 in the trajectory calculations (Mishap Investigation Board [MIB], 1999). The identified contributing causes of the failure were: modeling of spacecraft velocity changes, knowledge of spacecraft characteristics, trajectory correction maneuver TCM-5, systems engineering process, communications among project elements, operations navigation team staffing, training of personnel, and validation and verification processes (MIB, 1999). THE CASSINI MISSION Launched in October of 1997, the Cassini Mission was an international cooperative space effort conducted by NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA), and the Italian Space Agency (ASI). Cassini’s objective was to conduct a four-year scientific exploration of the planet Saturn and its largest moon, Titan, in an attempt to gain insight into the birth and evolution of our solar system (Ulrich, v.) The Cassini’s controversial use of both plutonium fuel (PO2) and 185 planetary swingbys brought the craft negative attention from the American Public because, even though detrimental PO2 effects could only occur by the highly improbable chance of explosion inside Earth’s atmosphere, NASA’s recent track record did not assure faith in imminent success. Currently, the Cassini is still on route to Saturn, having successfully looped the Earth. STS-93 The STS-93’s primary objective was to deploy the Chandra X-Ray Observatory. The orbiter chosen for this task was the Columbia, which had been used in twenty-six previous missions. During launch on July 23, 1999, an electrical shortage disabled two main engines’ computers. Examination of the orbiter upon return revealed that the origin of the problem was damaged wire that had been incorrectly handled during maintenance. The RFRM identified maintenance as a key issue for this mission. Several options for minimizing this risk were examined and it was recommended that NASA conducts more tests and hires more maintenance supervisors. THE MARS POLAR LANDER The purpose of the Mars Polar Lander was to explore previously undiscovered regions of Mars, namely the South Pole. The mission had three primary goals: to see if there was evidence of life, past or present; to analyze weather processes and history; and to determine the possible resources, if any, that exist on the Red Planet [Mars Polar Lander]. No space agency, American or foreign, had sent a probe to either the North or the South Pole; the MPL was supposed to be the first. The MPL was launched on January 3, 1999, and deemed lost 11 months later on December 3 rd. The primary reason for mission loss has been attributed to a design flaw that caused a premature shutdown of the landing rockets during touchdown. While premature shutdown was most likely the technical cause of mission loss, the real source of failure lies within the NASA organization and its management policies. As a “Faster, Better, Cheaper” baby, the MPL was nearly 30 percent under funded. The scarceness of money led to many problems, including insufficient time to properly test a few essential components. After the MPL crashed into the Martian surface, NASA and JPL were left shaking their heads and questioning why. Using the risk filtering and ranking methodology, over 400 sources of potential error were identified and, using this process, the field was narrowed to about twenty mission NASA Risk Assessment and Management Roadmap specific and NASA-oriented problems. Some of the major areas of error included “inexperienced project managers,” “improper software verification and validation,” and “elimination of oversight teams.” Number of Scenarios Distribution of Final Head Topics Head-Topic Organizational Scenari Scenario Name o ID A.7 Culture A.8 Human 2 1 un i m om C ca tio n Le ad er s M hi p an R ag es em ou rc en e Sy t Al st lo em ca s tio En n gi ne er in g Ex te rn al e So ftw ar e an wa r H ar d H an i za tio na l 0 O rg The RFRM was applied to minimize general risks at NASA. In each of the mission case studies, several hundred risks were successfully identified in phase I. These risks were then subject to filtering and ranking in phases II-V, with the following risks remaining after assessments and the removal of mission specific scenarios: 3 um COMMON FINDINGS 4 Fig. 5. Distribution of Risks under Head Topics Five policy options were identified for this risk scenario. Option A Risk Management Plan Do nothing Option B Assign responsibility of one employee within each sub-group to play role of an role independent oversight manager Faster B.1 Trust B.3 Stress B.5 Employee Indifference (Overlooking Problems) Maintenance Option C Re-assign current employees for oversight teams Option D Hire new employees to occupy internal oversight teams (One per project) D.2 Increased Use Without Increasing Verification and Validation Insufficient Testing Option E Hire external consultants as oversight teams Communication E.1 Inadequate Error Tracking Hardware C.1 Software D.1 E.3 E.2 Management G.2.1 Resource Allocation H.2 H.4 Systems Engineering I.2 Comm. Between NASA and contractors Communication between Subteams Inexperienced Project Managers Lack of Qualified Personnel Elimination of Oversight Teams Insufficient Supervision of Communication between Engineers and Teams Fig. 4. Common risk scenarios from the four mission case studies after the removal of mission specific hazards. Fig. 6. Policy options for the Elimination of Oversight Teams Application of the fractile method provided the expected percentage of errors for each alternative. An error is defined as the improper reporting, tracking, or handling of a problem in the system due to the elimination of oversight teams. Plotting these expected values against each option’s associated monetary costs and time delays created two pareto frontiers graphs, which graphically represent the trade-offs. For example, the trade-offs between two attributes, namely percentage of errors and cost, are exhibited in Figure 7. Multi-Objective Analysis (Cost) 600000 186 EE 500000 Cost ($K) To test the effectiveness of the remaining phases of the RFRM methodology, one scenario was chosen to advance into Phase VI, Risk Management. The selection of the scenario “Elimination of Oversight Teams” resulted from consideration of the overall distribution of the remaining scenarios under the various Head-Topics as well as their relevance to mission success. 400000 D 300000 Unconditional Exp Value D 200000 Conditional Exp Value 100000 C 0 0 20 B C A 40 B A 60 80 Percentage of errors that are not tracked properly Fig. 7. Pareto Frontier for Cost 2001 Systems Engineering Capstone Conference • University of Virginia A multi-objective trade-off analysis combining all three attributes, namely to make recommendations to NASA in order to eliminate, if not minimize, the risk of not properly handling errors. Multive-Objective Tradeoff (Size Indicates Costs) Time Delay (months) 14 D 12 REFERENCES B 10 8 C 6 E 4 2 A 0 0 10 20 30 40 Percentage of errors that are not handled, reported, or tracked properly 50 Fig. 8. Multi-Objective Trade-off Analysis of cost, time delay, and percentage of errors RECOMMENDATIONS An analysis of the scenarios remaining after ranking and filtering reveals that NASA is experiencing problems in nearly every organizational area. The five areas producing the most problems are organizational, human, software, communication, and resource allocation. This is not to say that the other areas are relatively problem-free; a different analysis may produce a different scenario distribution. NASA is one of the most important government agencies in the United States. It alone is responsible for expanding our knowledge of the universe. As a result, it must lower the current failure rate of its missions. This project revealed the effectiveness of the RFRM method in risk mitigation at NASA. The management plans chosen to handle the risks surrounding the elimination of oversight teams were either to assign current employees to man oversight teams or to hire new employees to occupy internal oversight teams. These solutions provided the best tradeoff between risk and cost of implementation. Further risk management plans can be developed and evaluated in the same manner previously discussed to handle the other major issues facing NASA. NASA employees represent some of the best and brightest scientists and engineers in the world. However, even the most dedicated and intelligent workers have their limit. Currently, NASA employees are overworked, underpaid, and faced with an environment that does not foster trust and open communication (MIB, 1999). Despite limited government funding, NASA officials must find a way to combat these issues facing their employees. NASA can explore its options like reductions in the number of 187 concurrent missions at each center better using the RFRM method described in this project. We feel that with improved communication, improved wages, and the addition of workers to reduce stress levels, NASA can maintain its current ambitions and return to its lofty status as the world leader in space travel and technological innovation. Derby, Stephen L. & Ralph L. Keeney. (1981). Risk Analysis: Understanding “How Safe is Safe Enough?” In Theodore S. Glickman & Michael Gough (Eds.), Readings in Risk (pp.43-52). Washington D.C.: Resources for the Future. Dickey, Beth. (2000, September). “Midcourse Correction: NASA discovers faster and cheaper don’t add up to better”. Government Executive, 29-38. Haimes, Yacov Y. (1999). Development of a Risk Management Roadmap for NASA. Virginia. Haimes, Yacov Y. (1998). Risk Modeling, Assessment, and Management. New York: Wiley-Interscience Publication. Haimes, Yacov Y., James Lambert, & Stan Kaplan. (2001). Risk Filtering, Ranking, and Management Using Hierarchical Holographic Modeling Framework. Charlottesville: University of Virginia. Hoffman, Edward J. (1996). “Issues in NASA Program and Project Management”. NASA Office of Management Systems and Facilities Scientific and Technical Information Programs. Washington: NASA. Intellectual Capital. (1997). “NASA's Shrinking Budget”. Intellectual Capital. Date Accessed: October 29, 2000. Date Posted: August 7, 1997. <http://ic.voxcap.com/issues/issue100/item4461.asp> Lawler, Andrew. (2000, April). “’Faster, Cheaper, Better’ on Trial.” Science, 32-34. Mishap Investigation Board. (1999). Mars Climate Orbiter Mishap Investigation Board: Phase I Report. Pasadena, CA: JPL laboratories. Molak, Vlasta (Ed.). (1997). Fundamentals of Risk Analysis and Risk Management. New York: Lewis Publishers. NASA Risk Assessment and Management Roadmap National Aeronautics Space Administration. (1999). NASA FBC Task Final Report. Washington: NASA. Shuttle Presskit. (1999, July). “STS-93: Shuttle Presskit”. Date Accessed: April 14, 2001. Date Posted: July 13, 1999. <http://www.shuttlepresskit.com/STS93>. Ulrich, Dr. Peter B. (1995) Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Cassini Mission (FEIS). Washington, D.C.: NASA. BIOGRAPHIES Jacob Burns is a fourth-year Systems Engineering major from Mclean, VA. His concentration is management systems. Mr. Burns principal contribution to the project was the analysis of the Mars Polar Lander in relation to the NASA risk assessment. He has accepted a position as a consultant for Anderson in Vienna, VA. Laura Kichak is a fourth-year Systems Engineering major from Silver Spring, MD. She has a minor in Economics and is concentrating in management systems. Her principal contribution to the project was the analysis of the Space Transportation System 93. Ms. Kichak has accepted a position at SAIC in Arlington, VA. Jeff Noonan is a fourth-year Systems Engineering major from Fair Lawn, NJ. His concentration is in Management and Computer Information Systems. Jeff’s principal contribution to the project was the analysis of the Mars Climate Orbiter. He has accepted a position with UBS PaineWebber in New York City. Beth Van Doren is a fourth-year Systems Engineering major from Branchburg, NJ. Her concentration is in History. Beth's principal contribution to the project was the analysis of the Cassini Mission. Beth plans to study for the LSAT this summer in hopes of attending law school in the near future. 188