week 7 contract

advertisement

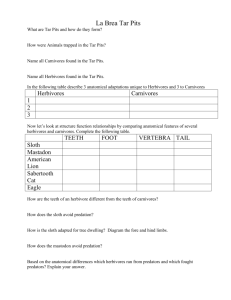

Localities of the Pleistocene: The La Brea Tar Pits When this photograph was taken around 1910, the location depicted was described as "the Salt Creek oilfields, 7 miles west of Los Angeles." Today, this spot is in the middle of downtown Los Angeles, eloquent testimony to urban sprawl, but the pools and deposits of asphalt still remain. For these are the La Brea tar pits, containing one of the richest, best preserved, and best studied assemblages of Pleistocene vertebrates, including at least 59 species of mammal and over 135 species of bird. The tar pit fossils bear eloquent witness to life in southern California from 40,000 to 8,000 years ago; aside from vertebrates, they include plants, mollusks, and insects -over 660 species of organisms in all. Tar pits form when crude oil seeps to the surface through fissures in the Earth's crust; the light fraction of the oil evaporates, leaving behind the heavy tar, or asphalt, in sticky pools. Tar from the La Brea tar pits was used for thousands of years by local native Americans, as a glue and as waterproof caulking for baskets and canoes. After the arrival of Westerners, the tar from these pits was mined and used for roofing by the inhabitants of the nearby town of Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de Los Angeles. The bones occasionally found in the tar were first thought to be those of unlucky cattle. It was not until 1901 that the first scientific excavation of the pits were carried out. Scientists from the University of California at Berkeley, notably Professor John C. Merriam and his students, were among the first researchers to work on the La Brea fossils. Today, the George C. Page Museum of La Brea Discoveries, right next door to the tar pits themselves, displays huge numbers of La Brea fossils. The Page Museum is part of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Life in Los Angeles was somewhat cooler and moister 40,000 years ago than it is today, as we can tell by examining the plant fossils from La Brea. Many of the plants and animals found in La Brea are identical or almost identical with species that still live in the area -- or that would be living in the area had Los Angeles not gotten in the way. Yet a number of the large animal species found at La Brea are no longer found in North America: native horses, camels, mammoths and mastodons, longhorned bison, and sabre-toothed cats. In today's ecosystems herbivores are much more abundant than carnivores. It is therefore curious that at La Brea about 90% of the mammal fossils found represent carnivores. Most of the bird fossils are also predators or scavengers, including vultures, condors, eagles, and giant, extinct, storklike birds known as teratorns. Why is this the case? If a pack of carnivorous mammals were to chase a lone prey animal into the tar pits, both predators and prey would become trapped. This would not have to be a frequent occurrence -- an average of one major entrapment every ten years, over a period of 30,000 years, would be sufficient to account for the number of fossils found at La Brea. Scavenging animals, drawn to feed on trapped animals, would have a chance of getting trapped themselves. This would explain the preponderance of carnivores and scavengers. A few denizens of the La Brea tar pits, now in the University of California Museum of Paleontology collections, are depicted below. Click on any picture to receive an enlarged version. Smilodon californicus Smilodon, the most famous of the sabre-toothed cats, is the second most common fossil at La Brea. Literally hundreds of thousands of its bones have been found, representing thousands of individuals. It was first described by Professor John C. Merriam and his student Chester Stock in 1932. Today, it is the California state fossil. But Smilodon was not restricted to California; it ranged over much of North and South America. For more about how this fearsome beast lived, you can visit our special virtual exhibition, Sabretooths!. Canis lupus furlongi This fossil was originally described as the species Canis milleri, but restudy has shown that it is a subspecies of C. lupus, the gray wolf. In the Pleistocene, gray wolves shared the region with C. dirus, the dire wolf. Gray wolves had the largest natural range of any mammal species except for Homo sapiens; at one time they were found in every habitat of the Northern Hemisphere except for deserts and the tropics. Today, the gray wolf has largely been exterminated in Europe, the United States except for Alaska, and Mexico. For more about La Brea, visit the George C. Page Museum, located by the pits themselves. The artist William Gordon Huff from Berkeley sculpted several of the animals from La Brea for the Museum of Paleontology's exhibit at the Golden Gate International Exposition of 1939 and 1940. You can view a virtual exhibit on Huff's sculptures for yet another perspective on life at La Brea. baby mammoth animatronic, it moves and trumpets; skeleton on left next to mom on right bison (buffalo), almost extinct due to overhunting; now lives on large preserves & recovering bones positioned in clear plastic acrylic to show you how they are in ground before dug up camel, now extinct in North America due to Ice Age cutaway clump of fossils showing how they are found in pit fossil lab: the director prepares a cart of fossil bone pieces for volunteers; you can volunteer fossil lab pic 2: a tray small bone pieces lower left; lights illuminate work area for very small piece cleaning, identification and preserving with glyptol fossil lab pic 3: various tools by trays of fossil bones spread out under magnifying lights fossil lab pic 4: two volunteers with rubber gloves on clean small bone pieces fossil racks: stored in trays in research areas of museum are huge #'s of bones gift shop: stop here when done for t-shirts, mugs, educational books and more mammoth skeleton full grown tusker oil wells in early Los Angeles around La Brea Tar Pits prehistoric life around the pits, mural; pronghorn antelope, this cute little member of the dear family lived here long ago sabertooth cat family; skeleton and skull; sabertooth cat attacking a sloth full color mural sloth skelton; a species survives in South America, feeding on Cecropia trees various skulls in display case vulture skeleton with painting of same vulture directly behind it http://www.rth.org/tarpits/ Why are the fossil skeletons on display in the Page Museum brown in color? The brown color results from the saturation of asphalt into bones over a period of thousands of years. Are the skeletons made of real bones? Nearly all of the skeletons on display are real fossil bones found at the tar pits. They have been mounted using an internal steel and wire armature . Missing bones or parts originally composed of cartilage have been reconstructed with resin or plaster. Only the Shasta ground sloth is 100% plaster because the bones of this species are rare from Rancho La Brea. In addition, the Columbian mammoth and American mastodon tusks are fiberglass, since the original tusks were dentine rather than enamel and consequently decayed in the asphalt. How old is the oldest fossil from Rancho La Brea? A wood fragment was dated at around 40, 000 years old using the Carbon14 radiometric dating method. When did the extinct animals found here live in this region? Extinct mammals, like the saber-toothed cats and mammoths, and birds, like Merriam's Teratorn and Grinnell's Eagle, roamed the Los Angeles Basin for several hundred thousand years. These and other extinct species were entrapped and their remains were preserved between 40,000 and 10,000 years ago at Rancho La Brea, during the last of four great Ice Ages at the end of the Pleistocene Epoch. How many fossils have been removed from Rancho La Brea? Since 1906, more than one million bones have been recovered representing over 231 species of vertebrates. In addition, 159 kinds of plants and 234 kinds of invertebrates have been identified. It is estimated that the collections at the Page Museum contain about three million items. What are the most commonly found animal remains? Dire wolves are the most common large mammals from Rancho La Brea, with several thousand individuals represented in the Page museum collections. The remains of over 2,000 individuals of saber-toothed cat rank second. Why are so many fossils found in a single asphalt deposit? Large deposits of fossils and asphaltic sand formed in the same location by cyclic build-up over thousands of years. The asphalt was sticky enough to entrap a variety of Ice Age animals, both large and small, and is an excellent preservative for plant and animal remains. How did the animals become entrapped? Asphalt is very sticky, particularly when it is warm. The warm temperatures from late spring to early fall would have provided the optimum conditions for entrapment in asphalt. Small mammals, birds and insects inadvertently coming into contact with it would be immobilized as if they were trapped by flypaper. The feet and legs of heavier animals might sink two or three inches below its surface. Depending on the time of day or year, strong and healthy animals may have managed to escape, but others would have been held fast until they died of exhaustion, or fell prey to passing predators. Under the right conditions, a single mired large herbivore would attract the attention of a dozen or more hungry carnivorous birds and mammals, some of which would find themselves trapped, providing more food for other carnivores. This cycle repeated during the 30,000 years that fossils were accumulating at Rancho La Brea. It is estimated that one entrapment episode involving ten large mammals every decade would furnish more than enough fossil remains to account for all the large mammal and bird fossils collected since the turn of the 20th century (over 1 million!). Is entrapment still occurring at Rancho La Brea? Yes. About 8 -12 gallons (32 - 48 liters) a day ooze and bubble to the surface occasionally trapping invertebrates (insects and worms), reptiles (lizards), birds (mostly pigeons, but also hawks, egrets, ducks, doves, and sparrows), small mammals (rodents and rabbits) and occasionally large mammals (dogs and humans) especially during warm days when the asphalt is softest. What was the Ice Age like in the Los Angeles Basin? Evidence indicates that four plant associations occurred in the region. Coastal sage scrub broken with groves of pines and cypress grew in the immediate vicinity of the asphalt seeps. Chaparral, with some pine and juniper scattered within, covered the slopes of the local mountains. In deep mountain canyons there were redwoods and other plants that mixed up slope with coast live oak and with a riparian (stream side) association in the canyon bottoms. Stream courses crossing the plain supported a riparian association that included sycamore, walnut and numerous herbs. Most of the types of plants that live here today were present here in the late Pleistocene. This indicates that rainfall was strongly seasonal, with most precipitation occurring in the late fall, winter and early spring, whereas the summer months were relatively dry. Many plant species found in these fossil deposits now only live along the summer fog belt from San Luis Obispo to Oregon and on the Channel Islands. A few species occur today in the southern Sierra Nevada Mountains between 4,000 and 6,000 feet elevation. This suggests that the late Pleistocene maritime climate at Rancho La Brea was cooler, more moist and equable than it is today. Are any of the fossils available for sale? The Page Museum does not sell original fossil material. However, reproductions in fiberglass resin of selected items from the Rancho La Brea collections are available for purchase through the Page Museum Gift Shop. A more extensive selection is available to other museums and universities through the Collection Manager of the Page Museum. What were the climate and vegetation at La Brea like when the extinct animals were alive? While under the influence of the waning Ice Age, La Brea's climate was somewhat cooler and moister than today. This climate produced a vegetation similar in type to that which presently exists on California's Monterey Peninsula, located approximately 300 miles to the north. Fossils evidence also indicates shallow ponds and marshes existed at La Brea. Intermittent streams transported drier inland vegetation as well as traces of redwood, which probably grew in sheltered canyons in the local mountains. What was the frequency of entrapment at La Brea? The 10,000 individuals mentioned in answer 14 became trapped during about 30,000 years of time (roughly 40,000 to 10,000 years ago). On the average this represents 10 animals caught every 30 years.