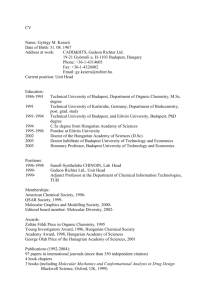

Tibor FRANK

advertisement