Implementing Occupational Hazards Intervention Program for Small

advertisement

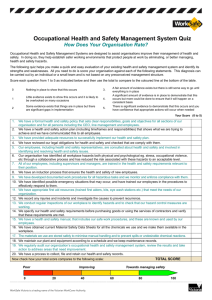

Implementing Occupational Hazards Intervention Program for Small Farms 2007 - 2008 Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute Fellow(s): Emmanuel A. Iyiegbuniwe, PhD Assistant Professor, Western Kentucky University College of Health and Human Services, Department of Public Health 1906 College Heights Boulevard, #11082 Bowling Green, KY 42101 Tel.: (270) 745-5088 E-mail: emmanuel.iyiegbuniwe@wku.edu Mentor(s): Daneen Farrow-Collier, MPH Public Health Advisor, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Acknowledgements: I wish to use this opportunity to say “Thank you” to all EPHLI staff, mentors, speakers and trainers whose efforts made the Institute a reality. I gratefully acknowledge the talented and hardworking efforts of Daneen Farrow-Collier, Nicole Kozma, and David Stroh for devoting their time and providing needed support throughout the EPHLI Cohort 3 program. To my EPHLI Cohort 3 fellows, thank you for believing in teamwork and networking. My participation in this program was made possible by the approval, recommendation, and support received from faculty and administrators at Western Kentucky University, including Drs. John Bonaguro, David Dunn, Gary English, Steve Nagy, and Wayne Higgins. Finally, my special thanks goes to my wife, Abiola and children (Emmanuel Jr., Joel, Chiedu and Chidi) for their support, sacrifices, and dedication throughout the EPHLI fellowship program. 2007–2008 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 211 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: In the United States, agriculture ranks among the most hazardous occupations. Small farm families are known to experience increased risks of occupational diseases, have more lost-time injuries, less production, and increased medical expenses. Physical hazards such as hazardous noise result from the operation of farm machinery including tractors, grain dryers, chain and electric saws, grinders, and other equipment. Although hearing loss due to hazardous noise is preventable through the implementation of hearing conservation programs, many small farmers lack adequate protection. There are currently no federal occupational health and safety regulations for small farms with less than 11 employees. Additionally, most small farmers often lack basic resources for the implementation of disease prevention and control measures. Education and support are essential for the success and effectiveness of any intervention program aimed at reducing occupational hazards among small farmers. The current project is aimed at developing and implementing an intervention program for capacity building to reduce occupational health hazards among a sample of small farmers in South-central Kentucky. Specifically, the project involved the use of questionnaires and occupational exposure assessment. Additionally, the project identified key stakeholders and various intervention options including engineering controls, substitution and the use of personal protective equipment by small farmers. Preliminary data indicate that most small farmers seldom use any form of hazard prevention or controls and that an intervention program such as this would be effective in increasing awareness of occupational hazards in farming. INTRODUCTION/BACKGROUND: In the United States, agriculture encompasses a wide range of sizes, ownership, business types, and other characteristics. Family farms account for 98%of all farms and 85% of total production. Although most farms are small (91% of farm count and 71% of farm assets), production has shifted to very large farms since farming has become increasingly consolidated and industrialized1-4. Small farms also differ in their contribution to agricultural production, product specialization, program participation, and dependence on farm income. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) defines a farm as an establishment that has or normally would have agricultural sales of $1,000 in a given year1. Accordingly, small family farms are those with less than $250,000 annual sales and are classified into five groups including limited-resource, retirement, residential/lifestyle, farming occupation/lower sales, and farming occupation/higher sales. Additionally, the USDA Economic Research Service has developed a farm typology that classifies farms into homogeneous groups based primarily on operator occupation and farm sales class3. The average small farmer practices polyculture, whereby a few acres are used to raise some cows as well as grow corn and vegetables simultaneously while large farms are generally monocultures. Small farms generate wealth in their respective rural areas through better housing, health services, education, local businesses, and the overall development of the local infrastructure and economy2. For the purpose of this project, small farms are defined as farming-occupation farms with less than 11 farmers whose operators report farming as their major occupation. 2007–2008 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 212 Problem Statement: A report by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) indicates that agriculture ranks among the most hazardous industries5. NIOSH estimates that at least 5 million and as many as 30 million American workers are exposed to hazardous noise levels. Workplace exposures to various physical, chemical, and biological hazards that occur among small farms with less than 11 employees are not currently regulated under the federal and state Occupational Safety and Health Act. However, many chronic diseases, illnesses, and health disorders in farming communities have been linked to agricultural exposures and these often take time to manifest6. Children and adolescents living on farms are also potentially exposed to farm-related health problems and may have increased risk of developing occupational diseases and illnesses. A number of published reports indicate that the affected farmers and their families tend to develop more lost-time injuries, less production, and increased medical expenses7,8. The majority of the physical hazards are produced as a result of operating machinery and equipment such as tractors, selfpropelled agricultural machines, chain and electric saws, and various repair equipment. Additionally, most small farmers often lack adequate resources to implement prevention and control measures for occupational diseases and illnesses. There are mounting pressures on small-scale farmers to learn new ways to produce income through alternative enterprises, improved marketing strategies, and management skills. Equally challenging will be integrating the increasingly complex and changing goals of environmental and occupational health policy (e.g., prevention and control of occupational hazards, water and air pollution) with agricultural policy. The USDA has noted that this helps farmers to improve productivity through resource management, controlling crop pests, soil testing, livestock production practices, and marketing. Although occupational illnesses such as hearing loss due to hazardous noise is preventable through the implementation of hearing conservation programs including the use of hearing protection devices, many farm families do not use adequate protection. There is need for small farmers to become more aware of potential environmental or occupational health hazards and applicable preventive or control programs. To be successful in their programs, educators and other stakeholders are being challenged to reconsider some fundamental beliefs, customs and practices about farming and what constitutes “success.” It is essential that small farmers “buy into” any occupational health preventive or control program. Communication and education are vital to long-lasting success. This depends on farmers obtaining “value-added education” and skillful application and/or proficiency in using such information. Figure 1 (Behavior Over Time) shows that the number of U.S. small farmers and farm families has remained stable over time. The USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service has noted that the relatively stable farm count over the last few decades reflects exits and entries essentially in balance2. However, available resources have been declining while the prevalence and incidence rates of occupational injuries and illnesses have been rising. Figure 1. Behavior Over Time 2007–2008 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 213 Variables Time Number of Small Farmers/Farm Families Occupational Health Hazards Available Resources for Intervention Programs Causal Loop Diagrams and applicable archetypes: Figure 2 shows the causal loops involved in maintaining and reinforcing the prevalence of occupational hazards among small farmers in South-central Kentucky. The focusing question is: “How can we prevent or control the risks of occupational hazards among small farmers?” An answer to this question lies in understanding and making a statement of the problem and depicting it in a suitable archetype: shifting the burden (Figure 3) as illustrated in The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook by Senge, et.al.7. 2007–2008 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 214 Figure 2. Causal Loop Figure 2. Causal Loop • These are small farmers, let them worry about it • I wish I could help, but there is nothing I can do. • We do not have the manpower or resources to develop adequate prevention or control program Lack of awareness, inadequate resources and non-existing occupational health regulations, for small farmers are reinforcing these models No action is taken to intervene on behalf of Small farmers continue to be exposed to many environmental hazards R Small farm families. Diagram 2007–2008 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 215 Government’s effort focuses on regulating health hazards in large farms We have always done it this way. Government does not care and we do not have the capability to control any hazards Small farmers have inadequate or no existing intervention programs B B Develop capability to ensure sustainable health and well-being for small farmers The goal of OSHA and employers in occupational health is to provide a place of employment that is free from hazards X Small farmers concern for increasing risks of occupational health problems and their lack of capability to prevent or control them B Desired Vision 2007–2008 Fellow Project 1 Develop the capability of small farmers to protect their wellbeing and ensure sustainable occupational health Develop programs (e.g., hearing conservation) Regular testing and monitoring Increasing use of controls (e.g., engineering, administrative and personal protective equipment) Awareness of intervention programs among small farmers increases 3 Improved farmers well-being and management practices Reduced occupational hazards Decreased costs of farming Alliances or partnerships with other stakeholders R X 2 National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 216 10 Essential Environmental Health Services: The field of environmental health is an applied discipline dedicated to the recognition, evaluation, and control of environmental factors or stresses arising in the environment that may cause sickness, impaired health and wellbeing, or significant discomfort among workers or citizens of a community. These factors or stresses may be chemical (e.g. solvents), physical (e.g. noise), biological (e.g. foodborne illnesses), or ergonomic (e.g. repetitive motion) in nature and may arise in virtually any sector of the environment. The Occupational Hazards Intervention Program will reduce the risks of small farmers in South-central Kentucky from developing workrelated injuries and illnesses. In fiscal year 1990, the US Congress directed NIOSH to develop an extensive agricultural safety and health program to address the high risks of health hazards and illnesses experienced by agricultural workers6. In 1996, NIOSH included occupational hearing loss as one of the priority areas of research with a consensus of 21 top research priorities and as one of the eight critical occupational diseases and injuries requiring research and development activities within the framework of the National Occupational Research Agenda (NORA)10. Specifically, this project addresses two of NORA’s priority research areas: NIHL and the inclusion of a special and underserved population of small farmers in rural areas. Through the development of occupational health hazard awareness and intervention programs, this project seeks to address the problems of environmental and occupational diseases. The benefits to small farmers include prevention of occupational diseases, reduced medical costs and lost wages. The project also addresses the assessment aspect of the IOM report and the Ten Essential Environmental Health Services (Monitoring Health, Investigation, Information, Education and Enforcement). National Goals Supported This research project is about implementing an occupational health hazards intervention program for small farmers. It will certainly contribute to the field of literature on occupational noise exposures and the development of hearing loss among farmers with a view to implementing a holistic educational and intervention program to address this pervasive but preventive disorder in South-central Kentucky. Additionally, the project will allow for the examination of multiple occupational exposures that contribute to other environmental public health injuries and illnesses. The main outcome is that the results of this research project have great potential of being applicable to other small farmers and special populations throughout the United States. 1. The research project is relevant to the CDC’s goals of Healthy People 2010 related to occupational health hazard exposures11. Specifically, the project addresses CDC’s goal of “Healthy People in Healthy Places” (promoting and protecting the health and safety of people who work by preventing workplace-related fatalities, illnesses, injuries, and personal health risks) through assessment (monitoring of health hazards through the use of questionnaires and exposure determination for noise and chemical hazards). 2. This project seeks to develop an awareness and intervention program that will reduce the risks of occupational hazards among small farmers. Additionally, by creating and disseminating knowledge, the project supports the national strategy of Public Health 2007–2008 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 217 Research. By encouraging the modification of existing farming equipment and implementation of relevant prevention and control measures, the project supports the need for public health protection of small farmers now and in the future. 3. The project addresses a number of guidelines and recommendations established by the American Public Health Association (APHA) for local public health leaders on the core non-technical competencies needed by practitioners working in local health departments. Specifically, this project focuses on the three primary functions of any environmental health program (assessment, management, and communication). Three graduate students are participating in this study and their assigned responsibilities include field data collection, analysis, interpretation and management (assessment and management), development and dissemination of questionnaires, and providing feedback to small farmers (communication). 2007–2008 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 218 Project Logic Model: Why, despite our best efforts, have we not been able to prevent occupational exposures and promote health and safety among small private farmers and their families? Key Stakeholders The key stakeholders are small farmers with less than 11 employees and their households. Farm families are concerned about their health, particularly work-related exposures and the development of chronic diseases such as hearing losses and would seek recommendations on prevention strategies and control measures to reduce their leisure-time and work-related exposures. Many farmers recognize that occupational exposures may cause irreversible hearing loss, social problems and stress, impaired communication, increased injuries, decreased self-esteem, annoyance, irritability, lost productivity, and increased medical expenses and workers’ compensation costs. Pre-conditions for Change Small farm and their families lack education, adequate financial resources and equipment for interventions, but are willing and able to invest time and effort needed to learn various ways to reduce exposure to hazards by implementing prevention and control measures. Table 1 shows the Cost-Benefit Analysis of Change or No Change. 1. Senior management alignment around vision. The proposed project addresses Western Kentucky University (WKU)’s Challenging the Spirit strategic plan that encourages faculty involvement in community-related research development and service activities that provide optimum services to the citizens of Kentucky. Additionally, the project involves a topic that is one of the priority areas of the National Occupational Research Agenda (NORA) that is administered by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) under its pilot research grants. 2. Willingness of relevant stakeholders to invest time and/or resources for learning NIOSH and WKU have committed to investing needed time and resources (grant to the tune of $7,000) to ensure that this project is accomplished. 3. Willingness and ability of stakeholders to make tradeoffs between the short- and long-term. Farm families are willing and able to make necessary tradeoffs to ensure that they reduce their occupational exposures and improve their overall health. 4. Openness to commonly held beliefs and assumptions. Yes, I believe that farmers and their families are willing and capable of embracing change as long as they know that it will reduce their occupational exposures and improve their overall health and safety. 2007–2008 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 219 Table 1. Cost Benefit Analysis of Change – No Change Changing Not Changing Benefits 1) Benefits of Changing 3) Benefits of Not Changing Increased return on assets, improved productivity, Comfort and predictability of profitability and sustainability doing business the old-fashioned Improved human well-being and environmental or traditional way management practices Fear of the unknown Decreased costs of farming over the long-term and tax incentives for business-related expenses Formal and informal alliances or partnerships to offer a comprehensive program for small farmers Complementary to existing cooperative extension services for small farmers Increased potential for government-funded programs Costs 4) Cost of Changing 2) Costs of Not Changing Short-term impacts resulting from time commitment Increased incidence and for limited resource small farmers in collaboration and prevalence of farming-related adapting/ implementing the new intervention program illness, disease or disability rather than doing business as usual Decreased incomes and business Moderate increase in physical capital needed for revenues program implementation Increased medical costs and hospitalizations More jobs being lost than created 2007–2008 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 220 PROJECT OBJECTIVES/DESCRIPTION/DELIVERABLES: Program Goal: To promote and encourage the implementation and promotion of environmental and occupational health intervention programs including education, prevention and control programs for small farmers. Education is key and support from stakeholders is essential for the success and effectiveness of any intervention program aimed at reducing occupational health hazards. Health Problem: A number of chronic diseases, illnesses, and health disorders of adults in agricultural communities are linked to occupational exposures and these often take time to manifest. Children and adolescents living on farms are also potentially exposed to farm-related health problems and may have increased risk of developing occupational diseases and illnesses. Small farm families are concerned about their health, particularly environmental and occupational health exposures and the development of injuries and acute or chronic diseases. They would seek recommendations on feasible prevention strategies and control measures to reduce their leisure-time and work-related exposures. Additionally, many farmers recognize that occupational exposures may cause such serious health problems (e.g., irreversible hearing loss, social problems and stress, impaired communication, increased injuries, decreased self-esteem, annoyance, irritability, lost productivity, and increased medical expenses and workers’ compensation costs). Outcome Objective: When farmers recognize the benefits of this program to sustain human and environmental health, they will be committed to investing needed time and resources to ensure its success. Other important stakeholders will also be willing to ensure that the goals of the program are accomplished Determinant: Agriculture is one of the most hazardous industries in the United States, yet government does not regulate small farmers. Farm families who often lack the awareness, adequate resources, empowerment and motivation to prevent and control occupational health hazards in their farms. Impact Objective: To examine occupational exposure sources and profiles during normal activities and identify specific areas and farming activities associated with potentially high physical and chemical exposures. Small farmers and their families are willing and capable of embracing change as long as they know that it will reduce their occupational exposures and improve their overall health and safety. Contributing Factors: Government does not regulate small farms. Small farm families lack the awareness of occupational health hazards, have inadequate financial resources and equipment for interventions, but are willing and able to invest time and effort needed to learn various exposure prevention and control methods. Process Objectives: To assess occupational health exposures for a sample of small farmers in South-central Kentucky. Farm families are willing and able to make necessary tradeoffs to ensure that they reduce their occupational exposures and improve their overall health. METHODOLOGY: The project is conducted to assess occupational health hazard exposures, primarily noise, of small farms in South Central Kentucky: farms in three counties as the intervention farms and Western Kentucky University (WKU) farms as the comparison farm. Three WKU faculty members and three graduate Public Health students were assigned the responsibility of field data collection and analysis. By using an interdisciplinary approach for 2007–2008 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 221 occupational health hazard exposure assessment, the study seeks to document work activities, the presence of chemical and biological substances of public health importance. The study covers a period of one year. Distribution of questionnaires and field sample collection were scheduled and conducted during normal farming seasons (planting and growing seasons). Questionnaires will be distributed to all adult participants in each of the intervention and comparison farms. Participants in each selected farm will comprise of adults who regularly work on the farm. Each participant in the intervention group was made to complete a formal consent form that explains the voluntary and confidential nature of this study and to agree to wear any applicable personal sampling devices throughout the monitoring period. None of the participants in the comparison group will be required to wear any personal sampling device. No recruitment incentives or compensation will be paid to the participating farmers. Additionally, the use and participation of individual small farmers in this project was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board. NEXT STEPS: The results of this project will be presented at the 2008 NIOSH-sponsored Pilot Research Program (PRP) symposium at the University of Cincinnati. The project also has a great potential for future funding, hence additional grant money will be sought from various federal agencies, institutes, and foundations to assess longterm applications of intervention programs to reduce occupational hazards among small farmers. Additionally, when completed, the results of this project will be disseminated to the affected small farmers and the professional environmental health community with a view to promoting and encouraging the implementation of environmental and occupational health prevention and control programs and among farmers. EXPECTED OUTCOMES: The project is on-going and the final results will be available by late spring 2008. However, preliminary data indicate that most small farmers hardly implement or use any form of active hazard prevention or control during normal farming activities. An intervention program such as this would be effective in increasing small farmers’ awareness of occupational hazards in agriculture. This research project has identified key stakeholders and various intervention options including feasible engineering controls, substitution and the use of personal protective equipment for the prevention and control of occupational hazards among small farmers. This project will contribute to a scanty field of literature regarding occupational health exposures among small farmers in Kentucky. In addition, the project will allow for the examination of other potential occupational exposures that contribute to the development of hearing loss among farmers with a view to developing a holistic educational and intervention programs to address this pervasive but preventive disorder. The main outcome is that the results of this project can be generalized to other special populations throughout the United States. It is anticipated that the project will provide an opportunity for interdisciplinary and experiential learning for the graduate students in environmental public health sciences have participated in field data collection and analysis. Education is key to the implementation of an effective intervention program that would increase the use of hearing protection during farm activities involving hazardous noise exposure. Through the development of educational and intervention programs, we can address the problem of environmental and occupational noise and this will benefit the Commonwealth of Kentucky in terms of prevention of occupational diseases, particularly hearing losses, reduced medical costs and lost wages for farm families. In the field of environmental and occupational health, the implementation of feasible engineering and administrative controls are preferred strategies to reduce or prevent chemical, biological, and physical hazards. By implementing this intervention program, many small farmers (although they may lack adequate resources) 2007–2008 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 222 would be able to effectively control their risks of occupational hazards to acceptable levels or below regulatory or recommended levels. However, where the implementation of an effective engineering control program is not feasible, the use of personal protective equipment (respiratory and hearing protection) would be the next best and most practical strategy to prevent the risks of occupational diseases and illnesses among small farmers. It is anticipated that the implementation of this intervention program would lead to increased awareness of occupational hazards, increase sense of empowerment and revenue for the affected small farmers and their families. CONCLUSIONS: Small farmers are known to experience increased risks of exposure to a variety of occupational hazards, often have more lost-time injuries, less production, and increased medical expenses. The majority of work-related physical hazards in agriculture result from farm machinery and equipment. There are currently no federal occupational health and safety regulations for small farms with less than 11 employees. Additionally, most small farmers often lack the awareness and basic resources needed for effective implementation of hazard reduction and disease prevention and controls. The project involved the assessment of occupational hazards, primarily noise among a sample of small farmers in South-central Kentucky with a view to developing and implementing an effective intervention and control program. Specifically, the project involved the use of questionnaires and occupational exposure assessment. Additionally, the project identified key stakeholders and various intervention options including engineering controls, substitution and the use of personal protective equipment by small farmers. Preliminary data indicate that most small farmers do not use any form of occupational hazard prevention or control measures while working on the farm. The expected outcome of this project is the increased awareness and capacity building for the prevention and control of occupational health hazards among small farmers in South-central Kentucky. An intervention program such as this would be effective in increasing awareness of occupational hazards among rural small farming. Education is key for the success and effectiveness of any intervention program aimed at reducing occupational hazards among small farmers. The project also has the potential of being applicable to small farmers throughout the U.S. 2007–2008 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 223 LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITIES: Emmanuel A. Iyiegbuniwe, PhD EPHLI has been very rewarding and challenging at the same time. The SKILLSCOPE 360 survey and MBTI provided opportunities for a deeper personal understanding, assessment of my skill level and relevant input from supervisors, colleagues, and students. Additionally, the sessions, assignments, classroom discussions, and group activities are invaluable in my career development with regards to improving my communication skills, tactical strategies and in designing programs for more effective communication and relationship skills with faculty, staff and students at my institution. I am excited about what I have learned that are necessary to improve my "People Skills" and the development of a more holistic and satisfying relationship with others. As a future leader in environmental health, I feel a good sense of accomplishment knowing that success favors the prepared mind and to always keep an open mind toward solving problems. I am very excited about the opportunity to attend a course on leadership and business development strategies in Southeast Asia, specifically Malaysia. Additionally, I have been awarded a summer fellowship by the Japanese Study Institute to attend a three-week course at San Diego State University. However, I fell short of accomplishing all my desired goals for this project. Specifically, I was not able to complete my project due to delays in receiving funding from the grant applications that I submitted. Nonetheless, I am grateful for the University of Cincinnati’s Pilot Research grant award of $7,000 from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). This funding is necessary to complete the project and subsequently inform EPHLI staff of my progress. I am confident that the Institute has provided me with a set of tools for continuous improvement and the development of a deeper understanding of leadership qualities in environmental public health. Looking back to the beginning of EPHLI Cohort3 one year ago, there is no doubt in my mind that active participation in the Institute has been a very challenging and rewarding experience. 2007–2008 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 224 ABOUT THE EPHLI FELLOW(s) Dr. Emmanuel Iyiegbuniwe (Ph.D., University of Illinois at Chicago, 1997) is an Assistant Professor of Environmental Health Sciences at Western Kentucky University, Bowling Green, KY. Dr. Iyiegbuniwe has over fifteen years of experience in academia, consulting, and industry in the areas of Air Quality Management, Environmental Health & Industrial Exposure Assessment, Epidemiology, and Public Health Management of Disasters. His teaching, research, and service interests are in the areas of agricultural safety, industrial workplace and indoor air quality (IAQ) exposure assessments for substances of public health importance. Dr. Iyiegbuniwe is an ATLAS scholar and Thomas Jefferson fellow. Additionally, Dr. Iyiegbuniwe is a fellow of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute (EPHLI 2007-2008), the American Industrial Hygiene Association (AIHA) Future Leaders Institute (FLI 2006), and Japanese Studies Institute. He is a member of several national and international professional organizations including the KPHA, AIHA, and APHA. Professional Experience 1989-1992 NGO Liaison Officer/Occupational Hygienist, Federal Ministry of Health, Lagos, Nigeria 1993–1997 Environmental Health & Product Safety Coordinator John Crane, Inc., Morton Grove, IL 1998–1999 Occupational Hygienist, Maxxam Analytics, Inc., Toronto, Canada 1999–2000 Industrial Hygiene Manager, Environmental Design International Inc, Chicago, IL 2000–2002 Senior Environmental Consultant, Theodore J. Hogan & Associates, Inc., Lemont, IL 2000– 2003 Adjunct Professor, Roosevelt University, Chicago, IL; College of DuPage, Glen Ellyn, IL; and Benedictine University, Lisle, IL 2003– Present Assistant Professor of Public Health, Western Kentucky University, Bowling Green, KY Awards (Selected) AIHA Future Leaders Institute (FLI) Fellow, 2006 Illinois Environmental Health Association Award, 1996 University of Illinois/John & Grace Nuveen International Scholar Award, 1995 National Safety Council/Campus Safety Association Award, 1995 Thomas Jefferson Fellowship/USAID Training for Leadership and Advanced Skills Scholarship, 1992-1994 Publications (Selected) Iyiegbuniwe, E., Chekuri, L., Iyiegbuniwe, A. (2007). Workers’ Exposures to Ultra-fine Particulate Matter during Automobile Components Production. Int. J. Nanomanufacturing Vol. 1, No.5, pp. 608-626. Iyiegbuniwe, E., Iyiegbuniwe, A., Chekuri, L, Lewis, J. (2007). Nanomaterials and Health: A Critical Review of Exposure Assessment and Control Strategies. Int. J. Nanomanufacturing, Vol. 1, No.5, pp. 574-591. Iyiegbuniwe, E., Chekuri, L., Iyiegbuniwe, A. (2006). Workers’ Exposures to Ultra-fine Particulate Matter during Automobile Components Production. Proceedings of the 5th International Surface Engineering Congress, October 2006, ASM International, Materials Park, OH 44073, ISBN-10:0-87170-843-4, Vol. 5, pp. 63-72. Iyiegbuniwe, E. (2006). Institute Uses “City as Text” or “Walkabout” Methodology for Student Engagement. Teaching Spirit, Vol. 18 No. 6, pp. 1-5. 2007–2008 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 225 REFERENCES 1. U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service. 2002 Census of Agriculture, Vol. 1: Geographic Area Series, Part 51: United States Summary and State Data, AC97-A-51, June 2004. 2. United States Department of Agriculture. A Time to Act: A Report of the USDA National Commission on Small Farms. USDA Miscellaneous Publication 1545, 1998. 3. US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, Bureau of the Census: 1990 CP2-1. 1990 Census of Population, Social and Economic Characteristics, United States. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1993. 4. U.S. Small Business Administration, Office of Advocacy. Characteristics of Small Business Employees and Owners 1997, January 1998. 5. NIOSH. “Criteria for a Recommended Standard: Occupational Noise Exposure.” Revised criteria 1998. Cincinnati, OH, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Accessed January 15, 2008. Available at (http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/98-126.html). 6. Thelan J, Davis W, Baker D, Hosokawa M. High-frequency hearing loss in male farmers of Missouri. Public Health Reports, 98, 268-273, 1983. 7. Concha-Barrientos M, Cambell-Lendrum D, Steenland K. “Occupational Noise: Assessing the burden of disease from work-related hearing impairment at national and local levels.” Geneva, World Health Organization (WHO Environmental Burden of Disease Series, No. 9), 2004. 8. NIOSH. “Work-Related Hearing Loss.” National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Pub No. 2001-103, Cincinnati, OH, 2001 9. Senge P, Kleiner A, Roberts C, Ross R, Smith B. The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook: Strategies and Tools for Building a Learning Organization. New York, NY: DoubleDay, 1994. 10. NIOSH. “National Occupational Research Agenda (NORA).” National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Pub No. 96-115, Cincinnati, OH, 1996. 11. US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010 (Conference Edition Volume II). Washington, DC: January 2000. 2007–2008 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 226