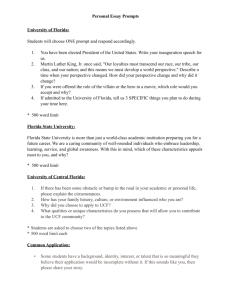

Florida Board of Governors - Academic Affairs

advertisement