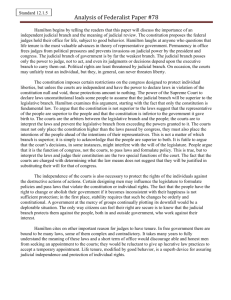

courts vs

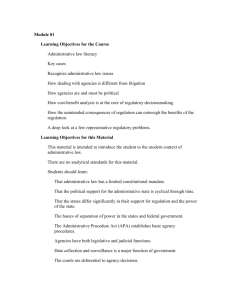

advertisement