Becoming a Black Manager

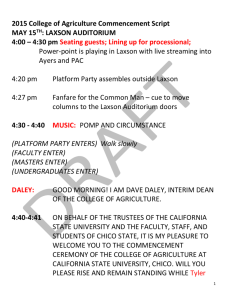

advertisement

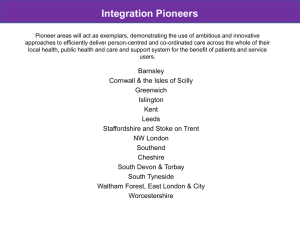

ESRC Teaching and Learning Research programme: Thematic Seminar Series (Jan 2005 – June 2006) Changing Teacher Roles, Identities and Professionalism Seminar 2 Professional Identities and teacher careers Becoming a Black Manager Dr Dona Daley with Dr Meg Maguire, Centre for Public Policy Research, King’s College London, Franklin Wilkins Building, Waterloo Road, London, SE1 9 NN Draft Paper 1 Becoming a Black Manager Abstract This paper explores the professional experiences of a cohort of thirty African Caribbean managers in the British education system set against and alongside the shifts in the social and political arena as well as in educational policy and practice over the last thirty years. The paper will focus on two inter-related themes. First, the ‘choices’ and progression of these teachers will be briefly explored and it will be argued that these teachers’ career decisions are not so much self-made but contextually and structurally informed. Second, the paper will argue that, over time, three distinct cohorts of black managers can be identified; the ‘pioneers’ who arrived in the UK in the mid to late 1950s; the ‘settlers’, some of whom may have been students of the pioneers and the ‘inheritors’ who took up post after 1988. Daley (2001, p. 239) argues that this typology has ‘echoes of the immigrant experience’ and claims that it often takes at least three generations for a people to settle in a new country. The paper concludes that in coming to understanding the professional identities of these teachers, and the gendered and racialised nature of their identity construction over the career course, it is critical to ‘read’ these accounts alongside the ways in which policy plays a part in this process. 2 Becoming a Black Manager The research and data set This paper is based on a set of thirty in-depth interviews (fifteen female and fifteen male teachers) conducted, coded and analysed by Dona Daley from between 1998 - 2001. Daley interviewed primary and secondary teachers of African-Caribbean descent who had an aspect of management in their job description. The choice of interviewees was dependant, in the first instance, on her personal networks (Zinn, 1979). As the work progressed, she extended her sample through snowballing techniques. As part of her methods, she was careful to place herself in the research setting. She had considerable school teaching experience and had worked as a senior manager in an urban secondary school (Daley 2001). As she says: “I would, by definition be studying people who were ‘like me’ “ (Daley, 2001, p. 81). Her theoretical starting points were influenced by the work of Goodson (1983); Sikes et al, (1985) and Day et al (1993). Drawing on this work, Daley claimed that a teachers’ career and life experiences shaped their view of teaching; that a teachers’ life outside school would impact on their work as teachers; and that it was important to locate the life history of the individual within the history of their time. In her research, she was concerned with the tensions between aspects of identifications and the job of teaching and in particular, the task of management. The ‘choice’ of teaching as a career In her interviews Daley asked the teachers about their reasons for ‘choosing’ to become teachers. One of her striking findings was that fifteen of the respondents had always considered becoming a teacher. “I had always wanted to be a teacher, ever since I was a little girl in Jamaica. I just saw myself as a teacher” (Barbara). Daley found that in her sample, many respondents saw entering the teaching profession as a way to “afford them an element of status, good conditions of service and a clear career route” (Daley, 2001, p. 106). Some had parents who had taught in the Caribbean; others spoke of the influence of teachers as significant role models: It was one of the only professions that I actually saw black people in. I wish I’d bumped into a few more brain surgeons when I was younger! (laughs) (Barry). (Daley, 2001, p. 107) They was a tacit recognition by many of the respondents of “a ‘certain ‘kudos’ to be attained” (Daley, 2001, p. 111) in becoming a teacher. In contextualising the ‘choice’ of teaching as a career, it is useful to remember that, in the UK, teaching has often been seen as a respectable and ‘safe’ job. In the past, for working class people, becoming a teacher was one way to access higher education and a professional career. For middle class women, along with nursing, it was one of the early employment routes open to educated women. For the older members of Daley’s sample, who started teaching in the 1950s and early 1960s, it might be argued that ‘choosing’ teaching as a professional occupation was a selection from what was available, an occupation that was culturally and socially acceptable – very much a tactical and pragmatic ‘choice’. “It was a really respected 3 qualification in the Caribbean” (Martin, in Daley 2001, p. 112). Certainly, for the African Caribbean community who settled in the UK in the 1950s and 1960s, and who were predominantly working class, becoming a teacher offered enhanced status and social mobility – as it had done for other working class communities in the past (Burn, 2001; Maguire, 2005). For many of the teachers whose narratives are deployed in Daley’s work, becoming a teacher was, in part, scripted by long-standing discourses about ‘respectable’ work and ‘improvement’. It was also, in part, sculpted by accessibility and availability. However, Daley points out that ‘choosing’ to be a teacher held out an additional promise for her sample: There is a very clear indication amongst the British born respondents that there was and is a role for them in this country as black teachers – themselves becoming role models for others and powerfully being advocates in the British school system (Daley, 2001, p. 112) This is a distinctive attitude to teaching as a career that has always inflected the professional identities of minority-ethnic teachers in the UK (Siraj-Blatchford, 1993; Maguire and Jones, 1998; Roberts et al, 2002). Black teachers have always highlighted their contribution in advocacy for minority ethnic students and their families (Irvine, 1989; King, 1992); Pole, 1999). Daley’s work also testifies to the tensions, complexities and difficulties involved for minority-ethnic people who ‘choose’ to teach because of this distinction. Her respondents all detailed times when they sometimes felt excluded in their teacher education and in their professional lives where they reported being ‘othered’ while simultaneously being the target of teacher-recruitment policy – needed because they were black and excluded for the same reason. Thus, for Daley’s sample, ‘choosing’ to teach and progression in teaching were tightly intertwined with multiple sets of identity and identifications. Drawing on the work of Mama (1995) and Rasool (1999), Daley argues that the subjectivities and flexible identities of people who are educational managers, who are women or men, who are of African-Caribbean descent and who are British, impacts their personal lives and professional sense of self. Daley’s point is that her sample inhabit their professional roles as teachers “yet they do not operate outside their identity as a black man or woman” (Daley, 2001, p. 124): Black people living in Britain often develop the skill of moving in and out of various subject positions with great alacrity in the course of their social relationships and interactions with a diverse array of groups in their personal, political and working lives (Mama, 1995, p. 120). One outcome of inhabiting these various subject positions is that the teachers in Daley’s sample sometimes had to ‘choose’ to act, or not to act in relation to their ‘racialised’ selves. Their embodied identities meant that many of the sample were expected to take on the role of black teacher very early on in their training “sorting out the black kids” (Martin). As Daley (2001, p. 126) says, “Being a white teacher does not carry the same responsibilities, demands and contradictions”: You know if things are too up front [about race issues] they think you are making a case and trying to rock the boat...(Barry) I'm not in favour of going overboard with every issue to do with discrimination or racism...but there is a place for that (Doreen) It seems that black teachers and black managers need to make a careful appraisal about which situations they should intervene in. It could be that not to speak about some circumstances in schools could be to collude with poor practice, yet to talk about every grievance that arose in 4 schools would mean that the teacher’s voice might lose impact over critical incidents. These sorts of ‘choice’ pressures can have an impact on the professional relationships that managers form and maintain with the staff and other adults with whom they interact. Their role as leaders and managers and in particular their role as black leaders and managers adds another dimension to the already complex micro relationships within an institution (Ball 1987): I think it was to do with this notion of having a black person telling them how to do their job, Telling them that they're not doing it as well as they might be...basically being in charge. Now think about it in this country, how many people in their wildest dreams think that one day that's going to happen to them? (Sonia) ‘Choosing’ to teach and ‘choosing’ career progression may well call up a series of shifts in subject positions; achieving progress in the teaching profession might involve equally complex manoeuvres. Progression in a teaching career Almost from the beginning of their careers, Daley’s sample were aware that as black student teachers and as younger members of the profession, they would have to fulfil a complex role in their professional lives. They were and are aware that their identity as black people in British society is sometimes in tension with their professional role. It is against this background that Daley’s sample decided to become managers. Their reasons for becoming managers are typified by Fay's comment and are probably not that different from the reasons that would be offered by many other teachers seeking promotion: I was frustrated in the classroom, I wanted to do more—when you are In the classroom you have access to 30 children and that's it, if you are in management you have access to the whole school.... But, if the initial ‘choice making’ of these black educational managers was, in part, scripted by what was available in terms of education, training and employment, as well as in terms of what was seen as desirable in terms of offering a degree of social mobility, progression was another story. Daley reports her contradictory feelings about this aspect of her work. She did not wish to contribute towards a “pathology of black managers” (p.124) but at the same time, she did not want to romanticise their progression. Undoubtedly they experienced obstacles, which were not the lot of their white managerial peers. Daley categorised the difficulties reported by her sample of managers as ‘external’ and ‘personal’ obstacles to progression. Before considering some of the obstacles reported by the black managers, it is necessary to highlight the structural location of these thirty teachers who have been successful in gaining promotion and who have made progression in their careers. The actual location constitutes a form of external obstacle. All of these managers were working in what Daley has referred to as ‘rough and tough’ urban schools. This finding is itself worthy of further exploration. Is this because black managers themselves select to work in these schools; is it because policy sometimes valorises the unique contributions that minority-ethnic teachers can make in urban settings; is it because it is difficult for black managers to obtain promotion in less challenging schools? Whatever the reasons, the outcomes have to be recognised – black managers may well be placed in schools where it may often be harder to ‘prove’ their efficiency and effectiveness –high stakes work indeed! Three of the five secondary black head teachers that Daley interviewed for her study were managing schools that were under special measures. (To be under special measures means that there is regular contact with Local Education Authority 5 (LEA) Inspectors and Her Majesty's Inspectors (HMI) with termly targets that have to be met). All but one of the respondents talked about the difficulties of working in 'challenging' urban schools. They were concerned with the ‘external obstacles’ of having to meet centrally and normatively derived targets, whilst working with children and young people who sometimes arrived in their schools with 'below average' scores. Yolanda, a head in a school under special measures, highlighted this issue: 80% of my year 7 has reading ages of 6-9. Two years from now, someone is going to publish a statistic that says that [...] school is failing. The miracle is that I beat up on the staff and enable them to produce the percentages they do (Yolanda) Yolanda was under pressure to improve the attainment of the students in her school. As a result, she developed a number of strategies (holiday revision sessions and Saturday School during term time) that would improve attainment. She recognises that she 'beats up on the staff'. Daley took this to mean that Yolanda was stringent about the implementation and evaluation of these strategies so that it could be shown that every effort was being made to improve her school. This could produce tensions between herself and certain sections of the staff, especially when she was personally aware that her staff were working in difficult circumstances, yet professionally needed to ensure that everything was being done to improve the academic standing of the school Meeting targets obviously challenges the management, governors and staff of schools in special measures. An added dimension to the difficulties that these managers encounter, is the fact they are black teachers running schools that are beset by difficulties and they are individually very high-profile. As Yolanda recounts: Well I think my problem here is that, as a black head teacher, people don't judge me as a head teacher, they judge me as a black head teacher. DD: What do you think the difference is? I don't have any room to get it wrong. I've got to get it right every time, I'm not allowed to get it wrong ever. I've got to get it right every time, because any time I make one mistake, it's “told you she couldn't do it...” People make decisions on my competence and my ability, and my capacity to work, based on the colour of my skin. They don't look at my intellectual abilities. (Yolanda) Yolanda is conscious that every aspect of her role and her identity is under scrutiny not only by the teachers in her school but also the parents and the Inspectors in the Inspection and Advisory team from whom she is expected to get support. Martin sees the tension between his role and identity not in dissimilar terms to Yolanda: I was conscious of the fact that being a black person in a school with lots of black kids… they want me to straighten these kids out. But I realised that in any position of responsibility and management as a black person, you are setting yourself up for people to shoot you (Martin) Whilst Yolanda and the other head teachers in the sample keenly felt the weight of their responsibilities as black head teachers, they were, to some extent, insulated by their role as senior managers of large institutions. Black teachers who work as middle managers for example, have more day-to-day contact with staff and more direct association with students. They are more likely to be affected by the sorts of personal obstacles to career progression that were reported to Daley in the process of her research. 6 When a teacher has attained a middle management post, they are likely to be preparing for further promotion. Many of the middle managers in Daley’s study reported personal ‘obstacles’ to their progression; they found it hard to get support to attend courses, they reported a lack of guidance about career development and a lack of support in their current posts. Other middle managers reported times when they believed that they were treated differently from their white peers. Marilyn sums up her perceptions thus: there is always going to be somebody who is the equivalent that can make the same mistake and not get the same flack. She described a very busy fortnight where she was monitoring a poor performing teacher in her department. She was also organising several events to celebrate Black History Month, which included several residences by visiting artists, theatre trips and so on. She had been late handing in a signed invoice during this time. The school secretary reported this to the head teacher: The head called me in and told me that he thought that I was a very good crisis manager, good at organising etc. but I must make sure that I had my paperwork in. (Marilyn) When she talked to other white heads of faculty to find out if they had been treated in the same way, she discovered that her treatment appeared to be unique. The other heads of faculty reported to her that their paperwork was routinely late due to pressure of work. Another respondent, Maxine had wanted to attend a three-day middle management course and had been refused permission to attend but discovered that other white members of staff were being sent on the course although they were not keen to go. There may have been a number of reasons why Maxine was not allowed to go on the course that she was not aware of, but nonetheless her perception was that she and other black staff always had a hard time when trying to access additional training. There were occasions when these sorts of decisions were challenged as she recounts: We [the black teachers] wanted to know the criteria being used to select people for the [middle managers] course. Apparently they had used information such as attendance and punctuality to make their final decisions, but still that didn't add up because there were several of us who had met those criteria... we were told that there would be no further discussion about the decisions made and the matter was closed. That was that! (Maxine) All the respondents in Daley’s study reported experiencing difficulties of one kind or another in progressing their careers. Many of the sample had applied for large numbers of jobs in order to attain a position of influence. All the respondents' management positions had been hard won, similar to black people in other occupations (Davidson 1997). But what Daley says typified her sample was their “ enormous capacity to overcome obstacles” (Daley, 2001, p. 125). Daley recounts the struggles of many in her sample in making progress. Yolanda and Fay left college as soon as they qualified because their families could not afford for them to go on for a fourth year of full time study to get the additional BEd qualification. Many years of part-time study followed their initial teacher education courses to develop professionally, gain promotion while raising a family. Yolanda makes this observation: They don't have the expectation that you will be successful... people didn't notice that you were coming. Then suddenly [they ask] how did you do that? The men in the study appeared to employ different tactics from the women in this cohort of 7 respondents. They were more direct when dealing with obstacles that came their way. Alan said that part of his professional repertoire was his directness and the need to be selfsustaining. Many of the managers in this study reported being 'the first' and sometimes 'the only' black teacher/manager in their school or local education authority. Clearly self-sustaining strategies were critical in these contexts. Daley claims that the managers in her study are used to dealing with ‘obstacles’ that they face because of their life experiences as black people living in the UK. On more than one occasion respondents made reference to the strength they gained from being practising Christians and having support from their local community (Channer 1995). Beverley talked about the 'legacy of slavery' and how this awareness has made her resilient. By this, she means her life has struggle and difficulty as a hallmark and that this is, in part, the nature of her existence and the black experience, which she has witnessed for as long as she can remember (see, for example, hooks 1993 and Angelou 1993). This history has afforded her fortitude and resilience to overcome whatever life may throw at her. This ‘resilience’ can be seen in what Maxine said, at the time when she was involved in an Industrial Tribunal case, yet still coming into school and working with the very people that she was bringing the case against: I think one of the things they were watching for was how long we would hold out for, you know, go off ill or become depressed or find some other medical term just to be out of school for a while. But I made sure that I was here everyday and I just kept a warm smile on my face and continued (Maxine). So far, in this paper, what is being suggested is that, as with other working class communities in the UK, teaching as a career has offered a step up into a professional occupation, and for this sample, into an occupation that has (historically) carried high status in the Caribbean. What is distinctive about this progression is that alongside an individual desire for social mobility and enhanced status is a strong collective commitment to the black community – not just in terms of becoming role models but, more powerfully, working as advocates to offer support and challenge social injustice. Black teachers are expected to take on complex racialised identifications in relation to their work in school teaching. These identifications pattern their professional experiences and play a part in ‘producing’ the black manager, as we shall see next. A typology of black managers Another significant contribution of Daley’s work on professional identities and teacher career is that she has traced the impact of time and policy changes in the construction of the black educational manager. Each of her three 'types' corresponds to the historic period in which the respondents concerned started teaching and the education policy and race inequity of that time as well as the career progress that they have made. Daley identified these ‘types’ as follows: ‘The Pioneers’: who had their early education in the Caribbean, who had completed their education in the UK and who have had the majority of their career in this country. Some of this group have taught in other countries. ‘The Settlers’: who have had all their education and training in the UK and who have 8 enjoyed a certain flexibility in their careers that, for a small minority, has included working in non inner city schools. The Inheritors’: ‘who are now middle managers (with no more than 15 years teaching experience at the time of interview) and whose employment in education appears to be limited to working in the inner city but who would like to have access to professional experiences in other kinds of schools. She recognised that her typology was only a heuristic device; that in reality there were overlaps and points of difference. However, the typology does help in exploring some policy dimensions to the story of the black manager. The Pioneers - being among the first The respondents in this first group had completed their training in the UK at a time when there were very few black teachers in the UK (mid to late 60s /early 1970s) (Braithwaite, 1962). Many trained in rural colleges often doing their teaching practices in all white schools. All these respondents had some of their education outside Britain. Three of the Pioneers reported a desire to teach from an early age: For me teaching was an honourable profession, it was making a massive contribution to society, and it was something which I could contribute towards if, and when I returned to the Caribbean, to Jamaica where I was born (Martin). Armed with a teaching qualification and some happy experiences of their time at college, the pioneers started to look for jobs. They all reported that they expected to work in their communities where they lived (Gilroy,1976). The Pioneers all talked about being supported by 'significant people' early on in their teaching careers. Sometimes the 'supporter’ was another Pioneer. Yolanda talks about a time when she worked with Alan: He was at that point a Head of Year, but he was also working in the Sociology Department and just his very presence gave me confidence because I was very unconfident.... So, in a way, I walked in his shadow... but also he did something. I told him that if I could find the courage one day, I wanted to be a Head of Year, and he said, 'Well you can be my deputy' he didn't have a deputy and he wanted me to be his deputy, he supported and encouraged me. Because there were few black teachers in the profession when they started, all the Pioneers know of each other or have worked together at some point in their careers. The Pioneers were very clear about their role in education and chose to work in schools where there were relatively large numbers of what were termed 'immigrant pupils' when they started teaching: I mean I was conscious of the fact that being a black person, a black man in all boys school, lots of black kids, 60% black in the school, right, well they obviously want me to straighten these boys out. (Martin). Earlier in his interview Martin had intimated that he had expected to follow an academic career but as a result of being 'offered' a head of year post, he could see that the role offered enormous potential. He talks about being sent black boys to discipline by his colleagues. In many ways, in accepting the post, Martin was formalising a role that had been assigned to him by his colleagues. For Anita, becoming a head of department meant that she was able to connect the roles of teacher and professional (in terms of developing a major department in the 9 school) and that of being a black woman taking on those roles and recognising what was required to ensure that the minority-ethnic students succeeded: I took it over (a department) and made a success of it, not by magic, but by being organised, and most importantly, I had high expectations of the children who were 60% ethnic minorities (Anita) The Pioneers got promoted 'through the ranks' (i.e. spending a great deal of time working in a number of middle management posts with varying degrees of responsibility) and spent all their careers in mainstream schools, usually gaining further qualifications through part-time study or secondment. In some cases they held particular posts for over ten years waiting for the 'right job' to come up. Their career progress is characterised by the notion of purpose, in that they had a desire to work in schools where they could be 'useful' as well as being able to be influential in the lives of young people that they came into contact with: So far, I've tended to work with those people who are from the most vulnerable sections of the community. So to be able to make a difference in their lives... you change peoples' lives, it's a wonderful power to be able to do that, it's just a tremendous power to do that (Alan) The Pioneers all have strong roots in the Caribbean. For them, teaching has always been an “honourable profession” that was respected in the community. Some of them qualified to teach in the Caribbean and expected to make the sort of career progression in the UK as would have occurred, had they stayed at home (Gilroy, 1976) (see 1). Daley calls this group the pioneers as they were among the first to ‘arrive’ in teaching in the UK (Foner, 1979). They commonly reported being the ‘only black’ child, student, trainee teacher, teacher in their educational progress through the system (Philips and Philip 1998). However, Daley argues that their presence in education was characterised by being ‘wanted’ by a number of educational authorities in the UK (Patterson, 1969). For the first time, a group of black teachers existed in appreciable numbers, so much so that the Caribbean Teachers Association was formed in London in the early seventies with over three hundred members (Gibbes, 1980). In a period when assimilation was being advocated, these pioneers were often involved in early agitation to develop more appropriate ways of working with newly arrived children from the Caribbean. The ‘pioneers’ were active in their communities and active in refuting the ‘deficit’ views of the black child that were in circulation in this period (see Coard 1971). Perhaps being in the vanguard of change lent a degree of optimism to the enterprise. As Daley (2001, p. 242) says, drawing on the work of Beryl Gilroy (1976): There lies at the heart of each interview of this cohort a very strong sense of being among the first black teachers in schools and the ‘responsibility’ that the position entailed. The Settlers- being needed Three of this cohort came to this country from the Caribbean when they were very young children. All the teachers in this second cohort of teachers received the majority of their education in the UK. Thus, the experience of this cohort of managers is totally British. The majority of the Settlers, in contrast to the Pioneers, had rapid promotion. Many of this second group of teachers rarely stayed in one position for more than four years. All the Settlers trained in the mid-late 1970s during what Barber (1996) describes as the 'last expansion of 10 education’. Like the Pioneers, the Settlers do not report negative training experiences. For many of them, their careers began in a similar fashion to the 'Pioneers'; they gained jobs in the inner city after their training: My teaching practices were in very good schools that gave me the opportunity to really develop my skills as a teacher. In fact, both my teaching practice schools wanted me when I left college but I felt it was important to work in multi-ethnic schools (Kwame) I had worked in all white schools whilst on teaching practice and whilst it was a good experience, I was clear that I wanted to work with mainly African Caribbean children where I could make a difference (Gilbert) What characterises the career progress of this group of teachers is that they seemed to be able to make informed career choices rather than proceed in the 'ad hoc' style of the Pioneers. All the Settlers commented about working in the community to which they belonged (i.e. the inner-city or where there was a considerable representation of black people). The Settlers were determined to make a difference in the communities that they worked in. In this context, their role as black teachers is ascendant. Two members of this group were able to spend time abroad on secondments that enhanced their professional development: I stumbled across the scheme and realised that white teachers, who had gone on an exchange for a year to the Caribbean, came back as 'experts' about black children. I felt that I should go to have the experience and bring back a different perspective. After all I was an expert in a different way yet at times it felt what I had to say wasn't valid because I hadn't had the same experience as white colleagues who had worked in the country for a whole year (Wilma) Wilma spent a year working in the Caribbean. It is useful to note how she felt invalidated because she had not had a Caribbean teaching experience. It was important to her that she became fully 'expert' in the eyes of her colleagues. The year in the Caribbean was useful to Wilma's career. She had been working in schools for about five years when a 'window of opportunity' became available for her cohort of black teachers. The issues of multiethnic education, equal opportunities and antiracist teaching were being firmly placed on the education agenda for a number of reasons (Tomlinson, 1998; Grosvenor,1997). Local authorities began to develop advisory teams and time-limited projects in response to recommendations from various Commissions (Rampton 1981: Swann 1985). Many of the Settlers had been encouraged into this work by an inspector or a head teacher or an advisor. Because of their 'lived experience', they were able to contribute in some form or other to the debate of multi-cultural/ antiracist education. In many cases, the experience of working in this field was to bring more than professional development: I gained valuable experience at the project. I was able to work with a team of African Caribbean teachers who were like-minded and were extremely supportive, I felt that we made a difference... (Gilbert) All the Settlers who were involved in multi-ethnic/ anti racist curriculum development projects comment about the 'good work' that they were involved in. This is probably due to the nature of the work and the fact that there was time for reflection to consider the impact they were having in schools. Working in numerous schools and working closely with heads and advisors in areas of development that were deemed to have a high priority in the inner city certainly got these respondents noticed. It may also be that the projects and other opportunities were timely and afforded this group of teachers a chance just at the time when they may have been considering 11 'what to do next' to further their careers. There is some overlap here between the Settlers' experience and Evetts' (1994) research into head teachers. She notes that specific innovations/policy enactments can act as springboards for career development: When they were young and aspiring teachers, the change to comprehensive schooling... presented them with an opportunity to develop their careers and for some, to receive very rapid early promotion. (Evetts 1994, p. 27) Whilst there can be some debate about whether the Settlers had rapid promotion or the promotion was timely, it was almost inevitable that they would make use of the opportunities that the curriculum projects of various kinds, afforded them. Unlike the arrival of 'comprehensivation' - a nation-wide phenomenon in which most local authorities were engaged - Section 11 curriculum development projects (specific curriculum projects funded with monies earmarked for working with pupils from the Commonwealth) were usually short term and were located mainly in areas where there were large numbers of black, Asian and other minority ethnic groups (Troyna and Williams,1986). The settlers were well positioned, in terms of their cultural capital, to offer expertise and leadership in the area of antiracism/multicultural provision. However, Daley adds that some types of 'capital' are more valuable than others (Bourdieu and Passeron 1977). Whilst multicultural and anti-racist education were seen to be important by some schools in large metropolitan areas, this was considered by many working in 'all white' areas as only something that inner city schools had to deal with (Gaine 1996). ‘Comprehensivisation’ could enable the teachers in the Evetts' study to work in any location. There may have been a limitation in how far one could 'stray’ from the inner city with the experience that the majority of Settlers gained. Daley believes that the Settlers experience is characterised by astuteness and the notion of forward planning. It is clear that all of this group were determined to have a career and knew what was necessary to progress in education (Hart, 1995). The Settlers enjoyed a fulfilling time professionally but recognised that to further their careers they had to 'go back into the mainstream'. As a consequence of their experience, many of them were able to attain posts in senior management teams and headships in urban schools. The settlers were educated against a background of growing politicisation and confidence in the British Black communities who were demanding equal rights and were angry about the discrimination and oppression they continued to face (Pryce, 1979; Fryer, 1986; Ramdin, 1987). National and local policy enactments (Swann Report, 1985; Troyna and Williams, 1986) were pressing for changes in the curriculum and pedagogy of schooling. The settlers were uniquely placed. There was, as Daley says (2001, p. 244), “no-one else other than these teachers who could do the job they did as effectively”. Policy had opened a window for progression for the Settlers’ careers. The Inheritors- being tolerated? The Inheritors do not seem to have had the same opportunities as their ‘brothers and sisters' in the Settlers cohort. This group trained during the mid to late 1980s and had no more than fifteen years experience as teachers at the time of interview. With the exception of one respondent, Herbert, this entire group was born in the United Kingdom and had all their education here. The majority of this group had 'done other things' (e.g. child care, working in industry or spent extra time getting essential qualifications) before entering teacher training. In general, Daley claims that the experience of this cohort seems to be characterised by 'missing 12 out' in some way. In the majority of interviews, she identifies an element of regret. Marilyn talks about having to gain a place on an access course and the course changing half way through (East et al, 1989). Maxine believes that if she had had the support at school when she was a child, which she had needed, she may have gained a place on a degree course to gain her teaching qualification. Other Inheritors told of how they gained their first degree at institutions they would not regard as 'first class' for one reason or another. The majority of this group report some disappointment with their educational progress. It appears that right from the start, the path to gaining the all-important teaching qualification was difficult for many in this cohort. The Inheritors are the only group who report having experienced racism in their training (Pole, 1999; Jones and Maguire, 1998). These experiences may have had an impact on their confidence once they left college. Marilyn acknowledges that her training was not a happy experience and implies that racism was at work in some situations. She reports feeling isolated because she was the only black student on an education course at a prestigious college: I found a lot of things awkward there. When you challenge people about things, they put you down the whole time and you felt inhibited that you then get into a position where you can't speak out any more and say anything. For example, we did this thing on language and we all sat in a circle, and the lecturer came in, apparently he was some big lecturer... he was going to tell us about language and all this kind of stuff, and he said “Hands up all of you who speak a language or have a background in another language”. And I put my hand up and this other girl put her hand up... So first of all he asked the girl what her language was and I think she said Spanish or Italian. He turned to me and said “What's yours?” I said it's a French Creole spoken in the Caribbean. He said “Oh no that's not a language”. Imagine how I felt......... The Pioneers, in the vanguard of change, knew that struggle would characterise their progression but they were organising for change and fighting against policies that excluded their communities and positioned them as a ‘problem’. They were fighting against assimilationist and integrationalist education policies (Tomlinson, 1977). The Settlers were needed and wanted in the multi-cultural and anti-racist policy context, and perhaps, superficially, this was a time of some changes – although mainly in specific locales. The career progress of the Inheritors has been characterised by continuing struggles and frustrations where education policies on race are still marginalised. Both Maxine and Marilyn spent a considerable amount of time at the beginning of their careers filling temporary posts. In the early eighties, there were many teachers who found it difficult to get teaching jobs, especially those who were not looking for jobs in the shortage subjects such as Science or Maths. In this case, ‘over-supply’ of teachers in schools meant that many newly trained teachers found it vary hard to gain employment. Maxine eventually became Head of a Religious Education department in an inner city school where almost half of the staff are black, there is a black head, and the majority of children are of minority ethnic descent. Working in a school with a large minority ethnic makeup has both positive and negative consequences for her. On the one hand, there was an opportunity to work in a proactive way in affirming the experience of black pupils through the curriculum, but on the other, there were problems that manifested in the staffroom. Maxine describes her first day at the school: A caucus of people [i.e. white staff] were looking at me as if to say, “here's another one” - that's what I was reading from them. Having heard things before I'd arrived I suppose it was easy for me work out what that was all about. 13 From interviews with this cohort, Daley identified a sense of frustration of not being able to gain positions of real influence. This frustration may have been due to the stage they were at in their careers (Dickens and Dickens 1991). The Inheritors have a 'depth of experience' (spending many years working in the same kinds of schools and amassing a wealth of experience in these inner city schools) and, like the Settlers, are beginning to realise that it is important that they develop a breadth of experience (working in a variety of schools to extend their experience) so that they are fit for further promotion. This group in particular, report that they feel that they are unable to make this progression and are more ready to describe situations where they construe inequalities taking place (Osler, 1997). They report feeling overlooked for internal and external promotion. There may be additional issues at work here too, as illustrated by Barry and George’s experiences. Barry and George work in the same boys school where 60% of the students are of African Caribbean descent. George had previously worked under two heads of departments as an RE teacher in this church school. On two occasions he had stepped in as Acting Head of Department before he was finally appointed as Head of the RE department. He then discovered that he was not going to enjoy the same employment conditions that the previous Heads of Departments had enjoyed. The post was 'scaled down' from a D allowance post to a B allowance post and the numbers of people teaching in the department were reduced, giving George a larger teaching load and greater administrative responsibility. George made this observation: “As Head of Religion in a C of E school, I didn't fit the bill basically”. He went on say that when high profile Christian visitors came to the school he was not introduced to them: It's hard to describe but I mean you know it when you see It, there's a certain type of person and I knew I wasn't that, so nobody ever came around... never visited my lessons... I felt constantly slighted, undermined, insulted by the whole thing... Barry occupies a cross-curricular role in the same school. He is in a position to develop a number of initiatives, if the resources are made available, but he is frustrated in his role as teacher because: The head doesn't trust me. Why? I'm black. Nothing that I have ever done should lead him to that conclusion... He doesn't allow me to do things... he has to check and double check. . If there is anything I want to do, organise a day trip or something then he should empower me. Now maybe he doesn't empower anybody, but that is not the impression I get. The impression I get is that other people can set things up and run with them. When pressed for examples, Barry provided the following detail: If the Careers department want to set up a careers afternoon, they can, but if I want to set up a Black History Day or a Reading Day; it's hard you know? If I want to do an assembly he [the head] wants to see the whole transcript of the assembly. Why? Why should it be problematic? Another emergent issue that may have an adverse effect on the Inheritors is the type of school in which they are able to gain posts of responsibility. Marilyn has this viewpoint: 14 Any school that was very 'nice', high academic type, I didn't get a look in. But any school that was inner city, or was based in an environment where the children would be challenging, then my application would be accepted and I would be invited to be interviewed. And I did actually say to [... her husband], no-one is going to employ me unless I work in these schools, I am not going to be able to work in a nice school, I am always going to end up working in these schools because that's what I can do. This example indicates an instance where her embodied identity is utilised to set parameters on what is professionally possible. Marilyn went on to describe three instances where she had applied to suburban schools and did not get the job, for what she described as rather 'pathetic' reasons. She describes a situation in her debriefing where the advisor didn't give any reason why she didn't get a post but simply said: “There are particular people for particular schools” and invited to her apply for several jobs in the inner city area of the same authority. Blair (1994) has claimed that as a 'by product' of the Education Reform Act, black teachers and students are structurally positioned in regard to the education market. Black students and black teachers are perhaps ‘less desirable’ commodities in the race for dominance in the league tables. As black teachers, the Inheritors like the Pioneers and the Settlers, see their role as working with black pupils in schools. However, currently the majority of black children are located in schools that face the most difficulty. There are other issues that are unique to this third ‘type’ of black education manager. In Daley’s sample, six of the inheritors came to teaching much later than the earlier cohorts and via other modes of employment and access routes (Callender 1997). If the access route and other non-traditional routes are an important source of minority ethnic teachers, then there will be a need to examine carefully the career progress of these teachers. Coming into teaching with additional experiences should put these teachers in good stead to progress their careers. At the moment, this does not seem to be the case. Conclusions Many issues emerge from this short review of the work of Dona Daley and in this paper I am aware of all the things that have not been said and not addressed. But what I want to do now is present some of my thoughts in relation to some broader structural issues. First, Daley undertook thirty in-depth interviews with a specific cohort of education managers of AfricanCaribbean descent. To a degree, they could all be described as successful; they have entered the teaching profession and have made some career progression. What of all those who are recruited but do not stay? What of all those black teachers who are have less fortitude and less resilience in the face of marginalisation and exclusion? “What keeps black teachers in the profession and what drives them away?” (Daley, 2001, p. 259). Second, it is important to reiterate that of the five Pioneer secondary head teachers, three manage schools that are (or were) under special measures. In terms of progression, Daley’s work highlights a lack of mobility for many Black teachers. Gaining depth of experience in the inner city might, paradoxically, contribute to their inability to work anywhere else, potentially curtailing the breadth of their career. The teachers in Daley’s study want to work in their communities to make a difference – not just “to ‘fill the gaps’ in the ‘rough tough’ schools which predominantly serve black and white working class youngsters” (Daley, 2001, p. 258). But they also want the same opportunities that other (white) educational professionals have in terms of career progression (Osler, 1997). They want to ‘operate’ as professionals but they also share an aspect of identification with their students – an identification that may sometimes 15 limit their careers as teachers: I say to the children that they are worth something... I say that I want something better for them… because you are black children, people will define you by the colour of your skin, because they do it to me (Yolanda). Notes 1. Beryl Gilroy came to the UK in 1951 from Guyana as an experienced teacher. She was forced to take a series of unskilled jobs before being able to resume her career in teaching. Bibliography Angelou, M. (1993) Wouldn't take anything for my journey now, London: Virago Ball, S. J. (1987) The Micro politics of the School, London: Routledge Barber, M. (1996) The Learning Game - Arguments for an Education Revolution, London: Victor Gollancz Blair, M. (1994) Black Teachers, Black Students and Education Markets, Cambridge Journal of Education Vol.24 No.2 1994: 277-292 Bourdieu, P. and Passeron, J. (1977) Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture London: Sage Publications Braithwaite, E. R. (1962) To Sir, With Love, London: Four Square Edition. Burn, E. (2001) Battling through the system: a working class teacher in an inner city school, International Journal of Inclusive Education, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp 85 – 92. Callender, C. (1997) Education for Empowerment- the practice and philosophies of Black Teachers Stoke on Trent: Trentham Books. Channer, Y. (1995) I am a promise (the school achievement of British African Caribbeans) Stoke on Trent: Trentham Books. Coard, B. (1971) How the West Indian did is made educationally subnormal in the British Education system: the scandal of the black child in schools in Britain London: New Beacon for the Caribbean Education and Community Workers' Association. Cornell, S. and Hartmann, D. (1998) Ethnicity and Race: making identities in a changing world California: Pine Forge Press. Daley, D.M. (2001) The Experience of the African Caribbean Manager in the British School System, Unpublished PhD thesis, King’s College London, University of London. Davidson, M. (1997) The Black and Ethnic Minority Woman Manager: Cracking the Concrete Ceiling London: Paul Chapman Publishing Ltd. 16 Day, C., Calderhead, J. and Denicolo, P. (eds.) (1993) Research on Teacher Thinking - an understanding of professional development, London: Falmer Press. Dickens, F. Jnr. and Dickens, J (1991) The Black Manager: Making it in the corporate world. New York USA: AMACOM East, P. Pitt, R. with Bryan, V., Rose, J. and Rupchand L. (1989) Access to teaching for Black women in Widowson Migniuolo F. and De Lyon 1989) Women Teachers: Issues and Experiences. Buckingham: Open University Press. Evetts, J. (1994) Becoming a Secondary Headteacher, London: Cassell. Foner, N. (1979) Jamaica Farewell- Jamaican migrants in London, London and Henley: Routledge and Kegan Paul Fryer, P. (1984) Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain, London: Pluto Press. Gaine, C.C. (1996) Working against Racism in largely white areas: Sites Themes and Outcomes, Unpublished Ph.D. thesis- Kings College London, University of London. Gibbes, N. (1980) West Indian Teachers Speak Out, London: Caribbean Teachers' Association and the Lewisham Council for Community Relations. Gilroy, B. (1976) Black Teacher, London: Cassell. Goodson, I. (1983) The Use of Life Histories in the Study of Teaching in Hammersley, M. (ed) (1983) The Ethnography of Schooling, Driffield: Nafferton Books. Goodson, I. (1992) Studying Teachers’ Lives, London: Routledge Gordon, J. A. (2000) The Color of Teaching, London: Routledge Falmer. Great Britain: Education for All (1985) Committee of Inquiry into the Education of Children from Ethnic Minority Groups (Swann Report) London: HMSO Grosvenor, I. (1997) Assimilating identities: Racism and Educational Policy in Post 1945 Britain, London: Lawrence and Wishart. Hart, A. (1995) Going for careers- not just for jobs, NATFHE Journal Vol.20 no.3: 16-17 Henry, D. (1991) Thirty Blacks in British Education: Hopes, Frustrations Achievements, United Kingdom: Rabbit Press Ltd. Home Office Report (1978) The West Indian Community: Observations on the report of the Select Committee on Race Relations and Immigration, Cmnd.7186 London: HMSO hooks, b. (1994) Teaching to transgress- Education as the Practice of Freedom, New York and London: Routledge. Irvine, J. (1989) Beyond Role Models: An evaluation of Cultural Influences on the Pedagogical Perspectives of Black Teachers, Peabody Journal of Education Vol.66 No. 4: 5163 17 Johnson-Bailey, J. (1999) The tie that binds and the shackles that separate: race, gender, class and color in a research process, Qualitative Studies in Education Vol.12 no.6: 659-670 Jones, C. and Maguire, M. (1998) Needed and Wanted? The School Experiences of some minority ethnic trainee teachers in the UK European Journal of Intercultural Studies, Vol. 9, No.1. pp. 79 -91. King, S. H. (1993) Why did we choose Teaching careers and what will enable us to stay? Insights from one cohort of the African American Teaching Pool, Journal of Negro Education Vol. 62 no.4: 475-492 Maguire, M. M. (2005) ‘Not Footprints Behind But Footsteps Forward’: Working Class Women Who Teach. Gender and Education Vol.17 no. 1 3-18. Mama, A. (1995) Beyond the Masks: race gender and subjectivity, London: Routledge McKellar, B. (1989) Only the fittest of the fittest will survive: Black Women and Education, in S.Acker, (ed) (1989) Teacher Gender and Careers, London: Falmer Press. Osler, A. (1997) Black teachers as Professionals: survival success and subversion, Forum Vol.39 no.2: 55-59 Osler, A. (1997a) The Education and Careers of Black teachers-changing identities changing lives, Buckingham: Open University Press. Phillips, M. and Phillip, S. T. (1998) Windrush: the irresistible rise of multi-racial Britain, London: Harper Collins. Pole, C. (1999) Black Teachers Giving Voice: choosing and experiencing teaching, Teacher Development Vol.3 no.3: 313-328 Pryce, K. (1979) Endless Pressure, Bristol: Bristol Classical Press Rassool, N. (1999) Flexible Identities: exploring race and gender issues among a group of immigrant pupils in an inner-city comprehensive school, British Journal of Sociology of Education Vol. 20 no.1: 23-36 Ramdin, R. (1987) The Making of the Black Working Class in Britain, Aldershot: Wildwood House. Roberts, L., McNamara, O., Basit, T. N. and Hatch, G. (2002) It’s like Black people are still Aliens, Paper presented at BERA Conference, University of Exeter, September, 2002. Sikes, P. Measor, L and Woods P. (1985) Teacher Careers and Crises and Continuities, Lewes: Falmer Press. Siraj-Blatchford, I. (1993) 'Race' Gender and the Education of Teachers, Buckingham: Open University Press. Tomlinson, S. (1998) New Inequalities? Educational Markets and Ethnic Minorities, ‘Race’, Ethnicity and Education Vol. 2 no.2: 207-223 Troyna, B. and Williams, J. (1986) Racism, Education and the State, London: Croom Helm. 18 Zinn, M. B. (1979) Field Research in Minority Communities. Ethical, Methodological and Political Observations by an Insider, Social Problems Vol.27 no.2: 209-219. 19