What Do We Mean By Religion? The Primacy of Ritual or Ethics

advertisement

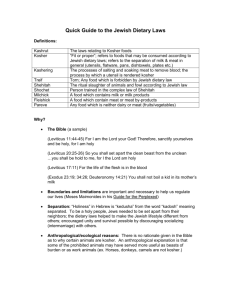

What Do We Mean By Religion? The Primacy of Ritual or Ethics Rosh Hashanah Second Day October 1, 2008 2 Tishri 5769 Rabbi Dennis C. Sasso Examine the Yom Kippur prayers of confession and you will not find one reference to ritual. There is no reference, for example, to putting on Tallit or Tefilin, to reciting the daily prayers, to attending Shabbat services or daily minyans; to dwelling in the Sukkah; no reference to eating trefe. The liturgy speaks only of moral failings; of violence and betrayal; of gossip and slander; of deceit and abuse; of cheating and lying. This season is a time of forgiveness for sins against our neighbors, offenses we are supposed to rectify and reconcile directly with those we have injured before receiving forgiveness from God. And yet, when we are asked what constitutes a religious person we often think first of ritual behaviors. We assume that praying, fasting on Yom Kippur, keeping kosher and dwelling in the sukkah, are Jewish qualities, while being a reliable and honest businessman, an ethical public figure, a caring and charitable person, a good parent, child or spouse are simply generic human traits. Such thinking is regrettable, and it is wrong. And that is why the events of this past summer surrounding the kosher plant in Postville, Iowa are so shameful and should give us pause to think about the abuses often perpetrated under the guise of religion. Many of you are familiar with the details. In l987 a Lubavitcher Hasidic family from Brooklyn, N.Y., moved to Postville, Iowa, a struggling farm community, to open Agriprocessors, a state of the art kosher meat packing and distribution facility. The company seemed to inject a boost into Postville’s economy. Soon, however, stories emerged of tensions between the newcomers and the locals. There were accusations of unsafe working conditions, child labor, failure to pay wages, and cruelty to animals. A raid by the Immigration and Customs Enforcement led to the arrest of hundreds of illegal immigrants. Workers were pressured to plead guilty to Social Security fraud in order to avoid months of detention and even longer sentences for identity theft. Laborers were reportedly held in chains and shackles and the women, released to care for their children, had to wear tracking ankle bracelets while awaiting deportation procedures. Two issues have begged for attention and correction: first, the unfair labor practices of the company and second, what many have regarded as an overly aggressive and inhumane enforcement of immigration law. There is, in this case, a third issue of concern for us as Jews: the alleged shameful actions of a business pretending to serve the needs of observant Jews. Agriprocessors was a “kosher sweatshop” trying to present itself as a business rendering a service to the religious community. 3/7/2016 1 The Kosher dietary laws have their origins in the Bible and have evolved over time. The thrust of “kosher” (which means “fit” or “proper”) is a dietary practice that seeks to ensure not only an appropriate ritual behavior but also a moral standard of eating. Rabbi Yisrael Salanter, the 19th century founder of the Musar ethical movement, denied kosher certification to a matza factory in Eastern Europe on the grounds that the workers were being treated unfairly. At the heart of the kosher dietary practices there is a humanitarian component. Originally they were intended to bridge a compromise between the biblical ideal of a vegetarian diet, and the human appetite to eat meat. The refrain associated with the Torah’s dietary injunctions is to become a “holy people.” For the Orthodox, the rationale for keeping kosher is simply “God (the Torah) says so.” For those of us who take tradition seriously without taking it supernaturally or literally, kashrut is an expression of Jewish consciousness and identity. Eating has played an important social and cultural role in the preservation of a distinctive Jewish tradition (what would Jewish life be without matza balls and kenishes, tarelikos and hamantashen, chopped liver and white fish salad, even if Bubbie’s Table has often yielded from “strictly kosher” to “kosher style”). But kashrut is not merely a ritual or social behavior. It has an ethical core, a moral dimension. A new initiative among Conservative rabbis is Heksher Tzedeck. It seeks to bring the ethical values of Judaism to bear upon kosher certification. The Reconstructionist movement has addressed these issues for decades. In a Guide to “The Jewish Dietary Laws”, to which I was a contributor, we established the core moral values which are now beginning to claim public attention. Central to these is the Jewish prohibition concerning Bal Tashchit: not to harm, destroy, or waste: Are we recycling? Are the foods we eat and the goods we buy harming the planet? This is a kosher issue. Judaism also teaches us about Tza'ar ba'alei chayyim: respect for animal life. Do we promote animal welfare? Do we eat foods of animals that are farmed and fattened in inhumane ways? This is a kosher issue. There is the health principle of Sh'mirat haguf: "protecting our bodies, preserving our health". Do we engage in proper exercise, nutrition, hygiene and diet? This is a kosher issue. The ancient rabbis developed laws regarding Oshek: "protecting workers and consumers from exploitation." Are we sensitive to labor issues surrounding the production of foods? Do we read labels and insist upon truth in advertising? This is a kosher issue. Then there is the tradition of Tzedakah: Do we promote justice through the sharing of food, money, and time with those in need? Do we remember Mazon, the Maurer Feed the Hungry Fund? This is a kosher issue. 3/7/2016 2 Goethe wrote that “a man is what he eats.” Jewish dietary customs are more than merely "pots-and-pans-theism." The way we eat and what we eat are statements about who we are, how we take in and relate to the world, about being responsible consumers. Rabbi Abraham J. Heschel lamented the great disconnect in modern religious life between ritual and ethics: “When faith is completely replaced by creed, worship by discipline, love by habit; when the crisis of today is ignored because of the splendor of the past; when faith becomes an heirloom rather than a living fountain; when religion speaks only in the name of authority rather than with the voice of compassion, its message becomes meaningless.” And yet, a recent opinion letter in The Forward weekly by two Orthodox rabbis rejects any efforts to tie Jewish dietary observance to ethical considerations. It gallingly states: “Why should an industry[s] average of wages or benefits serve as a guide to ethical conduct. Rabbis [should] specialize in law not…ethical principles.” The letter urges resistance to measures that “downplay the … kosher laws themselves in pursuit of a higher morality.” How can anyone speaking in the name of Judaism, least of all two rabbis, allow themselves such a Hillul Hashem, a desecration of God’s name. Rituals and traditions are important to religious and to secular life. There are patriotic rituals, like saluting the flag; national folk rituals like eating turkey on Thanksgiving; social rituals like kissing and shaking hands. Rituals provide an esthetic and emotional appeal; they are the pageantry, the color, the celebratory and commemorative side of life. They have a bonding effect. Words and acts hallowed by centuries and millennia of experience and collective memory, can add beauty and joy, depth and purpose to our otherwise disconnected existence. Most ritual belongs in the realm of minhag or custom, not din or law. They are folkways that vary from community to community and change from region to region and across the generations. Yet many people get hung up on ritual and really believe that God actually commands certain words and actions to be performed in a specific sequence to be effective. Religion becomes a quasimagical system of scrupulosity and obsessive behaviors, where pushing the right buttons, speaking the right words, compels the right response from God. Sadly, many rituals and prayers are practiced or recited by rote or from nostalgia; they become empty shells, remainders of a faith that no longer moves nor motivates, that neither enchants nor intrigues. Rituals should help us to express old values in new ways and new convictions in old ways. In the words of Rav Kook, they allow us “to renew the old and to sanctify the new.” Our challenge as modern Jews is to be spiritually bold in creating the words, symbols and rituals that will not only root us in the past, but invite us to affirm the present and embrace the future. That is why rituals change. That is why women now are called to the Torah and become rabbis. That is why we delete certain passages from the liturgy which may have made sense in their own times but are intellectually or morally unacceptable to us. Mordecai Kaplan observed that “people whose religion begins and ends with worship and ritual practices are like soldiers forever maneuvering but never getting into action.” The action part is the human agenda of respect and tolerance, of fairness and goodness, of justice and peace. 3/7/2016 3 Duties to God and responsibility to our neighbors, the “service of the holy” and the “performance of the good” go hand in hand. Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, Chief Rabbi of the British Empire, reminds us that in Judaism separating ritual from ethics is like causing “a cerebral lesion between the two hemispheres of the brain. Unless the holy leads us…toward the good, and the good leads us back …, to the holy, faith runs dry.” A kashrut which is just a set of archaic practices and recipes; prayers which are just citations from ancient poets and spiritual masters and not utterances of today’s yearning heart; rituals that look only to tradition without attention to renewal and transmission, do not constitute religion, but atavism; they are not expressions of faith and growth, but of fear and paralysis. Religious life needs to be rescued from decadence, impotence and decay; to become empowered, affirmative and creative. Kaplan reminded us that if “tradition is to grow it has in part to be outgrown.” I read recently: Tradition is a living thing that needs to keep its body limber. Otherwise, it gets stiff and calcified and, before you know it, the only place you’re liable to find it is under glass in a museum. Tradition is not past tense. It is all about the present…. To be in the presence of a living tradition is…to be able to taste it. The flavor is rich. (David Hoppe, NUVO, Summer, 2008) The struggle over the primacy of ritual or ethics goes back to our biblical beginnings. On Yom Kippur, the prophet Isaiah will challenge us: Behold, on the day of your fast you pursue business as usual, and oppress your workers. You fast, yet you quarrel and fight. Such fasting will not make your voice audible on high. Behold, this is the fast I desire: to loosen all the bonds of wickedness, to let the oppressed go free, to break every yoke. To share your bread with the hungry and take the homeless into your home. To clothe the naked when you see them, not turning away from people in need. Then you shall call and the Lord will answer…. (Isaiah 58:3-9) May we arise from our solemn season ready to translate the rituals and devotions of our tradition into the imperatives and challenges of our faith: “To do justice; to love mercy; and to walk humbly in the paths of godliness” (Micah 6:8). 3/7/2016 4