The Lorax, Criminology and Capitalism: Can Criminology speak for

advertisement

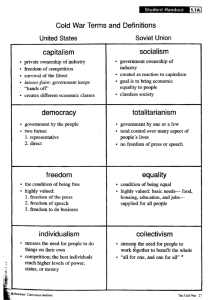

The Lorax, Criminology and Capitalism: Can Criminology speak for the Trees? Michael J. Lynch Department of Criminology University of South Florida In this post I draw upon environmental lessons offered by Dr. Seuss in The Lorax, and James Lovelock, an environmentalist, to explore the intersection of environmental issues, political economy, and criminology. The Lorax, published in 1972 was published two years before Lovelock’s well know Gaia Theory. Both works explore deteriorating environmental conditions in relation to expansion of economic development. Background: The Lorax, Lovelock, Ecological Destruction, Science and Capitalism “I am the Lorax. I speak for the trees. I speak for the trees for the trees have no tongues.” So said the Lorax, or rather so said Dr. Seuss through the Lorax in the early 1970s. Its now 2012, and many people in the modern world have failed to learn the lesson the Lorax taught us in Dr. Seuss’s book. That lesson is that people must speak for the environment because it cannot speak for itself. But perhaps not everyone would quite agree with this statement. In the early 1970s, James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis proposed the Gaia hypothesis. That hypothesis, now accepted as a scientific theory and principle based on significant scientific evidence, posed that the earth was a living system. In Lovelock’s more recent books, he essentially takes the position that the living system of earth is indeed talking to us -- its talking to us through climate change. Its not talking to us in any conscious way, but it’s still talking. Lovelock proposes that climate change is in essence the world speaking. If one understands Lovelock’s position, his point is that climate change is the living system of earth reacting to the ways in which humans behave. By exploiting the environment, depleting rain forests and other ecological systems, and rapaciously consuming fossil fuels without considering the consequences, humans have forced the world‘s climate system to change in response to those actions. In this view, climate change is the process through which the earth moves toward a new state of equilibrium in an effort to preserve itself. Part of that preservation system is raising the temperature in ways that cause a decline in the quality of the earth’s living system to reduce the number and volume of each species placing stress on the planet. Of course, the culprits behind the problem are humans, but since the earth is not a conscious living system, it is unable to respond or isolate humans as the problem. So, the earth isn’t consciously choosing to eliminate humans, it is driven to do so by humans who are changing the structure of the earth’s living system. The new equilibrium the earth is reaching will preserve earth as a planet, but the conditions established in doing so will become inhospitable to most life that currently occupy earth. In this sense, the earth’s living system is a structural system, and operates according to its own internal, structural rules. Those structural rules mean that earth will adapt a new structural form to insure that it is not eliminated. Doing so may eliminate earth’s species, but earth isn’t too worried about that. No, earth is acting like humans have for centuries, selfishly to promote its survival. And earth essentially has no choice in the matter. Driven by natural laws and the rules of physics, the earth is turning up the temperature to eliminate the force disturbing its survival -- humans. It is in this structural sense that the earth is speaking to us. In making this suggestion, Lovelock is not implying that as a living system, earth has consciousness, but rather that it has rules of order. The earth isn’t purposefully targeting humans, and even though humans turn out to be, along with earth and other species, the victims of climate change, this is a rather unintentional consequence of earth protecting its own survival. The fact that humans and the earth’s living system have become incompatible has been known for some time. Their current incompatibility, however, does not mean earth and humans cannot coexist. To be sure, they have coexisted throughout tens of thousands of years. What humans have failed to learn about their peaceful coexistence with the living system of earth is that there are structural rules that must be followed in order for humans to coexist with earth’s living system. What humans have failed to learn is how to behave properly within the rules of earth’s living system. Scientists have divulged these rules to us, but that doesn’t mean we follow them. The continued growth of industry in ecologically unsustainable ways and the facilitation of that growth by not only the economic system of capitalism, but by politicians, means that societies fail to pay heed to the rules of coexistence scientists have discovered. At this point in world history, if humans want to keep existing, they must learn and adapt to the rules of the living system of earth, and that means drastically altering human lifestyles and forcing economic change and requiring politicians to act in ways that promote this outcome. Scientifically, the processes that lead to climate change have been known for centuries and have been added to human knowledge piece by piece over a long period of history. These facts about climate change weren’t all put together in an appropriate way until the last few years of the 19 th century. And it wasn’t until the mid-20th century that scientists got a real handle on the process of climate change. But, beyond those scientists who understood what was happening, humans didn’t seem to care or take notice as the earth around them warmed and a host of environmental changes were induced. Industry rebuked the science of climate change, and used its economic power to influence politicians to accept the idea that climate change was some kind of fanatical scientific conspiracy. We are well beyond the point in human history and the scientific study of climate change where such skeptical views about climate change can be said to make any sense. Despite that most obvious conclusion and the extraordinary scientific consensus on the science of climate change, nations continue to act too slowly to control the human activities that promote climate change. Worst among these nations is the US, the world’s largest consumer, it biggest climate change culprit in terms of its ecological footprint, and the only nation that has failed to sign the Kyoto Protocol, an international climate change treaty. For much of the last four centuries, humans were too busy perfecting the development of society and their economic systems and political systems to pay much attention to the planet they lived on. In fact, one could argue that humans seems totally unaware that they lived on a living planet and that their behavior harmed that living entity. Ironically, the people that modern people refer to as “primitive” peoples understood the idea of the earth as a living system, and their religions revolved around the living systems of earth and they did much to protect the integrity of that system. In place of these holistic approaches to human societies, humans developed antagonistic relationships with nature. Somewhere in history, human’s started to exploit nature for its raw materials, which marked the beginning of the end for humans. Humans became obsessed with the idea of developing their social and economic arrangements, and with continually expanding their exploitation of nature and the growth of economic production as an indicator of human development. But far from being an indicator of human development, economic accumulation turns out, in hindsight, to be an indicator of the volume of harm humans commit against the environment. Throughout the ages, the more humans “progressed” economically, the more they destroyed nature and converted the materials of natures living system into commodities, transforming nature’s useful materials in to so much useless stuff -- useless as far as the earth’s ability to maintain itself. And as they “progressed” economically, humans paid less and less attention to how they were affecting the earth. Once humans invented capitalism and succeeded in spreading it across the globe, the final chapter of humans as earth’s exploiters was written. Capitalism and the earth cannot coexist. The result of capitalism inherent drive to exploit nature and turn nature’s work into commodities destroys earth and its ability to reproduce itself and the conditions needed to sustain species. But capitalism and its internal logic of accumulation drove humans forward in an unending quest to take over the value produced by nature, and to convert that value from its natural forms into economic forms that humans could possess and store and count up as some humanly created construction for measuring the worth of human societies. In converting raw material into capital and energy, humans were driven by the internal expansionary logic of capitalism. Because of its own internal focus, the system of capitalism fails to perceive that its goals and the accumulative desires it creates cannot be attained without destroying nature and hence the survival of humans. Some might say this is the ultimate expression of the Freudian death drive. As Dr. Seuss’ Lorax points out, in exploiting nature, continually accelerating that exploitation, and converting nature into commodities and energy, humans neglected their impact on nature, and ignored the fact that nature was finite. At the same time, the system of economic and social relations they had build on capitalism could not conceptualize the idea of finite value or limits to raw materials in the natural world. Capitalism could not admit these limits, for if it did, its internal driving force, accumulation, would be dislodged and destroyed, and the core component driving capitalism would be erased. Asserting that natural resources and nature has no limits was, from the start, clearly an error in thinking and the logical construction of capitalism. Clearly, the earth could only have so much value embedded within in it; so many resources that humans could exploit; could absorb only so much change and so much heat energy without changing dramatically. The resources on the planet were, from the inception of capitalism, finite and limited. No one reached out and periodically distributed more resources across planet earth. What was in earth was definite and finite, and the more of earth humans converted into commodities or transformed into energy, the less of that substance earth possessed for its own needs. Once humans used up resources, they were gone. Now, the bigger problem for humans is that they used resources in ways that not only lead to their depletion, but to the transformation of raw materials into other substances. Humans discovered coal and oil and natural gas, and burnt it. At some point while this was happening, there were those among us who knew better -- they had discovered laws such as the laws of nature and the conservation of energy which basically could be used to tell us that too much production was bad because it transformed energy and moved it from one state of matter to another, and that doing so had consequences. Indeed, scientists had already done experiments relevant to this issue in the 1500s. The proponents of capitalism, however, didn’t pay much attention to these physical laws of the earth or to science if it could not be employed in the productive process. Instead of respecting the laws of nature, humans substituted their own rules of capitalism, and proceeded as if those rules would override the laws of nature. As we have seen, this was a bad choice; capitalism cannot make up its own rules to override the rules of nature. Nature’s rules will always win. What the Lorax told us in the 1970s we have continued to ignore. How could a child’s story book character understand the world better than economists, political scientists, and world leaders? Apparently, the Lorax was an unrecognized genius. In the 1970s, Dr. Seuss looked around him and understood that we could not continue as we had -ignoring the living world system. He used the Lorax to teach us an important lesson. And yet, this is a lesson criminologists seem not to have understood. The Lorax, Lovelock and Criminology To learn the relevance of the story of the Lorax in a criminological context, try this experiment in class. Give students an assignment -- read “The Lorax” by Dr. Seuss and write an essay on its relevance to criminology. They will look at you, like criminologists would, as if you had two heads. But make them do it anyway. There will be some that have no clue what to write, and they may return to class with blank pages. But, what you will find out is that some of your students get it, and they will be more than willing to share their views with the class and promote a discussion of the limits of criminology and its failure to address environmental problems. That’s really what the Lorax is all about. Your student become the Lorax -- they will speak for the trees, the waterway, the species of the world, and they will wonder out loud why criminologists don’t get it. They will express their confusion that criminologists as social scientists don’t have the simple grasp of the world around them that Dr. Seuss did. This discussion can lead to a broader understanding that its not just criminologists who don’t get it, its social scientists in other disciplines as well, and environmental leaders, economists, and politicians who makes the rules about protecting the environment. The Lorax speaks because the environment can’t. Criminologists can speak, yet they don’t see the environment as worthy of their time, as deserving their protection. After all, the crime problem is, in the tradition of criminology, a problem of street crime, of people robbing and stealing from each other and the consequences of those actions. In the human book of values in the modern era, taking from and exploiting nature is not a crime; rather it is viewed as a necessity. But in robbing and exploiting nature to “progress” and accumulate wealth, humans ignored that they were, at the same time, robbing humans as a species and other species of the things nature provided that were necessary to life. A few humans became wealthy in the process; most got along; and significant numbers suffered because the “progress“ generated by producing wealth was not created to benefit everyone equally. All along, nature suffered at the hands of humans, and the benefits of “progress“ were not returned in any way to nature. The story of the environment and its relationship to humans is the same story as the relationship of the robber to his or her victim -- it is the story of humans robbing and stealing from the environment without regard for the consequences of their behavior. When a corporation exploit’s the earth, we don’t say its stealing. We don’t conceptualize the raw materials around us as belonging to us or even to nature. We view them as nature’s “gifts.“ We do not see ourselves as robbing nature because we have invented a political economic system that has displaced our ability to think of our human relationship to nature as one of criminal to victim, and instead see nature only as a gigantic warehouse for humans to visit where there is no price or consequence. The Lorax in his own way reminds us that we are offenders, and that we have long victimized the planet, and in so doing, have caused extensive harm. But, that is not the only moral the Lorax gives us. He tells us as well that our behaviors are unjust -- that we are engaged in actions of social, economic and ecological injustice when we take from the planet without regard for our actions. In doing so, the Lorax speaks for the trees for the trees have no tongues. He implores us to do the same and to learn that lesson, for without that lesson, we will exploit the world around us and do so until we have exploited our way into extinction. We may end up owning a lot of nature when we go, but we’ll be going just the same. Criminals exploit non-criminals; humans exploit nonhuman and humans, and don’t seem to distinguish much among the exploited except that sometimes, we feel better about exploiting nature than we do about exploiting humans. In this sense, humans are a funny lot. Crimes are acts of exploitation, acts of one human exploiting another for various reasons criminology has long attempted to decipher. We exploit others for their property, to build a self image and gain status, or for whatever other reasons we can invent. But, when we take from nature, when we violently disrupt nature, when we destroy nature, we don’t see ourselves as exploiters or as engaged in acts of violence. Yet, if Lovelock is correct -- and scientists who now accept Lovelock’s Gaia hypotheses as a theory would seem to suggest -- the world is, like other human beings, a living system. When we take from it, we do harm to it in the same way a criminal does harm to his or her victim. But, rather than seeing the world as a living entity, we prefer to follow along with capitalism’s ideological depiction of the world as being simply a warehouse of items for our taking. We are taking what is there for us, and in taking we are not doing any damage, we are simply doing what the theory of capitalism describes for us as the right thing to do - take from nature to build the accumulation of wealth, and to keep taking without thinking about taking and its consequences. What capitalism wants is for us to behave as a young child; to see the things around us, and to desire them all. The young child does not have the capacity to understand what it does. Apparently, neither does capitalism or its proponents. Capitalism wants us to have uncontrolled desires, and yet at the same time, wants to constrain us when our uncontrolled desires are redefined as crime because instead of taking from nature, we take from other humans. The Lorax understands that capitalism presents us with a lifestyle that is a gigantic contradiction. Capitalism drives humans to exploit nature and to be unconcerned with that exploitation. Yet, at the same time we exploit nature and participate in that exploitation, we destroy the very basis of our means of living. In the act of exploiting and destroying nature, we destroy ourselves. The Lorax well understands that capitalism and ecology are antagonists and dialectically opposed to one another. Capitalism cannot exist without exploiting nature, and nature cannot exist with capitalism exploiting it. Nature can exist without capitalism, and has done so long before capitalism emerged. Nature does not need capitalism; capitalism needs nature. Yet, among its many contradictions, capitalism destroys the source of its wealth by destroying nature, and is too impetuous in its child-like desire for uncontrolled accumulation to understand what it has done -- to see that it unmakes itself and its future and the future all of all humans every time it is successful in meeting the requirements of its own driving forces and in its subjugation of nature to the goals of capitalism. One of the hidden messages produced by the earth’s reaction to human exploitation emerges by uniting the story of the Lorax with the science of climate change, and specifically the views of Lovelock. As noted, Lovelock’s view essentially state that the world’s temperature is increasing so that the world can rid itself of species causing environmental stress. If, in doing so, the world was a conscious actor, as criminologists we might be willing to view climate change as the living system of earth’s revenge or as an act of retribution. And there may be something useful in depicting climate change as revenge. But, since the world lacks consciousness, it can’t really be seeking revenge, and rather consequences such as climate change, or increasing rates of illnesses such as cancer that stem from human environmental exploitation are really structural matters. In human terms, we may be willing to think of this as revenge, but in reality the result is nothing more than the rules of science enforcing themselves. The Lorax also knows since nature cannot act and has no voice, it cannot speak up about capitalism. What it must do, according to Lovelock, is create the conditions where the species responsible for its destruction vanishes unless, of course, the Lorax is successful in speaking for nature. There are many scientists and ecologists who have acted as the Lorax in the human world. But they, like the Lorax have been defeated -- the Lorax by the Onceler, the scientists and ecologists by the capitalist. The Lorax’s message, and the version presented as well by Lovelock, is one that most criminologists have yet to learn. To illustrate this point, let us for the moment consider just a small fraction of environmental costs of capitalism in the US alone. The reason to undertake this brief review of environmental issues is to highlight the large scope of harm humans commit against the environment -harms that most humans, including criminologists ignore. Criminologically, we can say that those who practice criminology have failed to apply the logic of their discipline to a broader understanding of crime and victimization, a point raised by green criminologists. Environmental Damage in the US: A Big Total and Picture In 2010 in the US, the 21,302 facilities that reported toxic release emissions under the auspices of the Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) program reported releasing 4.0 billion pounds of toxic waste. Anyway you slice that figure, that’s a large quantity of waste -- but not just any kind of waste -- toxic waste. If we examine the TRI data over the past decade, we see that the quantity of toxic waste has been shrinking in the US. Some might point to that outcome as evidence that environmental rules created to protect the environment in the US work. But there is another cogent explanation as well -- that the volume of toxic waste produced in the US has declined as manufacturing has been shifted to other nations. This decline in toxic waste in the US is not an indictor that environmental law is effective, but rather that capitalism is effective in following its own internal logical. As the cost of producing in the US has risen, and following what is now a long term, forty year trend, capitalists have increasingly move production from the US to other nations to take advantage of lower costs of production. And as capitalists move jobs overseas, employment in the US becomes less stable, the number of well paying manufacturing jobs declines, and average incomes have stagnated. Whatever its cause, we can examine the data over the past decade to get an idea of how much toxic waste has been dumped into the American environment. In the year 2000 US facilities reported 6.6 billion pounds of toxic releases under the TRI. We can estimate that in the decade that followed (20002009), US corporations released 53 billion pounds of toxins, or about 13,970 pounds of toxins per square mile of US territory. Most of those toxins are released in a small space, so that the 82% of the US population living in urban areas, which the US government estimates covers 3% of US territory, is exposed to significantly more toxic waste. From these data we can estimate that the volume of toxic waste emitted in urban area is somewhere around 353,000 pounds per square mile. That’s a lot of waste in a small space, and its detrimental to human health. But that toxic waste indicates that some sizeable proportion of nature has been destroyed in the production of that waste. How much of nature is destroyed to create 53 billion pounds of waste? It depends on whose estimate we employ. From relevant literature, we can estimate that the 53 billion pounds of waste emissions is about 40% of the volume of resources employed, so that if there are 53 billion pounds of waste, the raw materials extracted from nature totaled 132 billion pounds. The US also produces about 250 million tons -- or about 500 billion pounds of solid waste annually according to the EPA -- about ten times the volume of toxic waste. Thus, over ten years, and assuming that there has been a reduction in solid waste, that’s about 5.5 trillion pounds of waste. If we apply the same raw material-waste reduction as above, that 5.5 trillion pounds represents 13.75 trillion pounds of raw materials. Thus, combining these figures, we can see that in the US over the past decade, about 6 trillion pounds of toxic and solid waste has been produced, and 14.25 trillion pounds of raw materials used. Large straight 7 wheel dump trucks hold about 26 tons of material. So, the toxic and solid waste produced in America could be held in 115.4 Million large dump trucks, while the raw materials used would fill 274 million large dump trucks. Those figures may be so large that they are incomprehensible. But, even if we make the scale of comparison smaller, we can still see a tremendous environmental effect. For instance, copiers alone use 400 million pounds of toner each year in the US. That 400 million pounds represents much more in raw materials that must be extracted from the living planet. If we assume the same reduction standard, then in one year 990 million pounds of raw materials may be needed just to produce copies toner. To use that toner, it is applied to paper. American businesses alone consume about 30 million trees a year for its paper copies, and 37% of that paper ends up discarded in the trash. Since an average logged tree weighs (50 foot hardwood) weighs about 7,000 pounds, with a similar sized soft wood tree around 5,000 pounds. Assuming the wood in this example is one half hardwood and one half soft woods, 30 million trees weigh 180 billion tons, so the waste paper from this process alone comes to 66.6 billion pounds. An easier way to understand the total ecological costs of capitalist production in the US is to refer to the ecological footprint. The ecological footprint measures the volume of natural capital consumed in a nation. It’s a measure of the volume of land and sea area needed to produce the resources people consume. The world average is 2.7 hectares per person (or 6.7 acres). The US contains about one billion hectares, or about 3.2 hectares per person. The average person in the US, however, consumes enough to use up 8.0 hectares (about 20 acres) -- meaning that to maintain its standard of living, the US must obtain 4.8 hectares of land per person for its use from some other nation. American consume nearly 3 times as much as the average world citizen, and consume commodities that require 150% more ecological space than is available in the US. In terms of exploitation, Americans must not only fully exploit all of its land resources to meet its consumption level, it must also exploit 1.5 other countries the size of the US to meet its consumption level. Given that ecological resource-consumption imbalance, the US cannot have a balanced international trade ledger, because it consumes -- 1.5 times more -- than its possible to make in the US, and must get those resource from some other nation. The problem is that these consumption figures and their environmental impacts measure only the US impact. Worldwide, consumption has steadily risen as other nations try and mimic the kind of economic success the US has had, and as the world’s population continues to growth. From 1960-2000, the world’s population doubled. During the same forty year period, consumption quadrupled. The world’s ecology simply can’t keep pace with both of these trends -- and can’t keep pace with the increase in even one of these trends. What Does all this mean, Criminologically? Let me get straight to the point -- what all this means is that criminology has become quite irrelevant to the major problems in the world today. And its become irrelevant in different ways. Around the world, for example, crime has been in decline in many advanced nations -- or so say criminologists and agencies that measure street crime. But, that measure of crime omits from view the tremendous volume of environmental harm and crime that is committed world wide. That problem is not receding. So, while the type of crime -- street crime -- criminologists examine has been dropping, and while numerous explanations for that crime drop have been proposed, none provides a sufficient and efficient explanation of the crime drop. And at the same time street crimes that attract criminological attention declines, crimes that escape the gaze of criminology expand. Criminologists also did not predict the crime drop before it happened. This is likely due to the fact that the theories criminologists employ to explain crime are both inefficient, and because criminologists could not imagine crime’s decline given its long term rise. Finally, one could also say that criminology has become irrelevant with respect to another of its major concerns -- protecting victims of crime. Since street crime has declined, and that decline has little to do with criminology or its policies, and since the vast major of crime related victimization is not the result of street crime but is the result of crimes criminologists largely ignore (environmental and corporate crime), criminology also seems to have become quite out of touch with the reality of crime in the contemporary world. Much more needs to be explored on this point, and in an upcoming post, I will examine criminology’s irrelevance further, and explore the end of criminology in relation to the meaning of contemporary environmental problems.