APS_summaries

advertisement

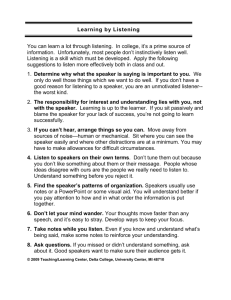

The Art of Public Speaking Chapter 1 - Speaking in Public Similarities between public speaking and conversation 1. You organize your ideas --in your head or on paper 2. You tailor your message to your audience 3. You adapt to your listener. Differences between public speaking and conversation 1. Public speaking is very structured - time limits, detailed preparation 2. Public speaking requires more formal language - correct grammar, no slang 3. Public speaking requires a different method of delivery voice, posture, dress Nervousness is normal - most people include speaking in front of an audience as one of their greatest fears - stage fright Dealing with nervousness 1. Get as much experience as possible. 2. choose a topic you care about and practice, practice, practice. 3. Think positively - not negatively (I’m not a great public speaker” --> “No one’s perfect, but I’m getting better with each speech I give.”) 4. Visualize yourself being successful. 5. Know that others can’t see how nervous you are. 6. Don't expect to be perfect--no one will know if you make a mistake. The Speech Process Speaker Receiver Situation - time and place message feedback interference (external – in the environment or internal – inside yourself) Chapter 3 – Listening Hearing – a physiological process Listening – paying attention to and making sense of what we hear Without training we usually grasp only 50% of what we hear. After 24 hours we remember only 10% of what we heard. Executives rank listening as #1 important skill. Listening is important in university - @ 90% of time is spent listening to lectures - strong correlation between effective listening and academic success - careful listening helps you get new ideas for speaking Four kinds of listening to improve critical thinking 1. Appreciative – for pleasure (music, comedians) 2. Empathetic – to provide emotional support (a friend in trouble 3. Comprehensive – to understand (lecture; directions to a new place) 4. Critical – to evaluate (used car salesperson; political candidate; TV ads) (Question for discussion: What kinds of listening will you be doing this summer in this program?) Four causes of poor listening 1. losing concentration; losing track; mind wandering 2. listening too hard; concentrating on all the facts rather than the main ideas 3. jumping to conclusions; second guessing the speaker; reading too much into a conversation; putting words into the speakers mouth; prematurely rejecting the speakers words 4. focusing on delivery, clothing, voice rather than the message (Question for discussion: How do I know if you’re listening?) How to be a better listener 1. practice listening 2. be an active listener; stay focused 3. tune out distractions 4. don’t prejudge by appearance or delivery (ex. Abraham Lincoln; southern drawl) 5. listen to the end of the speech; don’t pre-judge Focus 1. listen for the main points 2. listen for supporting evidence Develop effective notetaking skills Notetaking skills - help you concentrate and remember speaker’s main ideas - use keywords or outline instead of trying to write every word a speaker says Note: A person can talk much faster than you can write. Summary – Being a better (effective) listener can make you a better speaker. The Art of Public Speaking : Appendix Organizing your Speech * Note: Words in bold may be new for the students. Preparing Your Speech Developing your first speech (the ice breaker) 1. If teacher does not assign topic, choose an interesting topic, one that you feel knowledgeable about, one that you feel passionate about. 2. Narrow your focus for a short speech (but not too narrow). - You can’t summarize your life in 3-5 minutes. - Choose one or 2 noteworthy or interesting experiences. 3. Paint a picture with words. 3. Audiences like humor, jokes, funny situations if you feel comfortable with humor. Organizing the Speech – introduction, body, conclusion (Tell the audience what you’re going to tell them, tell them, tell them what you told them.) 1. Introduction (Tell the audience what you’re going to tell them) – get the audience’s attention - ask a question - tell a story - make a surprising statement - use a quotation 2. Body (Tell them.) - chronological - most important facts least important facts - compelling evidence - use transition words / statements to help audience switch gears 3. Conclusion (Tell the audience what you told them.) - let the audience know your speech is almost finished - reinforce / review main points - end on a clever or thought provoking note Delivering Your Speech Speaking Extemporaneously -- don’t write down every word you plan to say -- do write key words and phrases (on index cards or sheet of paper) -- do practice to become familiar with main points of your talk -- do think of extemporaneous speaking as telling an interesting or amusing story to a group of friends without notes Rehearsing Your Speech -- do practice—it will help you give a smooth delivery -- do practice out loud, not just in your head -- do have family or friend listen and give feedback -- do time your speech Presenting Your Speech -- do take a few deep breaths before you go up in front of your audience -- do establish rapport—look at your audience and smile -- do use gestures if they feel natural -- don’t rock from foot to foot -- don’t read your speech -- do keep going if you forget a part of your speech -- don’t put your hands in your pockets -- do maintain eye contact with your audience -- don’t talk in monotone; do use an expressive voice Chapter 4 -- Selecting a Topic and Purpose Choosing a Topic (p.86) Definition: the "topic" is the subject of the speech. Some topics are based on students' personal knowledge and experience--most people speak best about topics with which they are most familiar. Conversely, preparing for a speech gives a student the opportunity to investigate a challenging new area of knowledge. Brainstorming for Topics: Take a personal inventory of experiences, interests, skills, beliefs. Cluster ideas around the following nine general topics: people, places, things, events, processes, concepts, natural phenomena, problems, and places and policies.....then make sub-lists for promising ideas. Use reference "keywords" or a subject-based internet outline (e.g. Yahoo) to generate ideas. Determining the General Purpose (p.93) Definition: the "general purpose" is the broad goal of the speech. Usually this will one of two options: to inform or to persuade. To inform, the speaker needs to convey information clearly, accurately, and interestingly. To persuade, the speaker needs to advocate for a cause and change the attitudes of the audience. Determining the Specific Purpose (p.93) Definition: the "specific purpose" of a speech is a single infinitive phrase that states precisely what a speaker hopes to accomplish in his or her speech. Five tips for formulating the specific purpose statement: 1) Write it as a full infinitive phrase and not a fragment 2) Express your purpose as a statement, not as a question 3) Avoid figurative language in specific purpose statement 4) Limit your specific purpose statement to one distinct idea 5) Make sure your specific purpose is not too vague or general Troubleshooting questions for your specific purpose statement: 1) Does it meet my assignment? 2) Can I accomplish my specific purpose in the time allotted? 3) Is it relevant to my audience? 4) Is it too trivial for my audience? 5) Is it too technical for my audience? Phrasing the Central Idea (p.100) Definition: the "central idea" is a one-sentence statement that sums up or encapsulates the major ideas of a speech. This is the "residual message" that you want the audience to remember after it has forgotten everything else about your speech. Four guidelines...the central idea should: 1) be expressed in a full sentence 2) not be in the form of a question 3) should avoid figurative language 4) should not be vague or overly general Chapter Five: Analyzing the Audience 1. Audience-Centeredness: A. Keeping the audience foremost in mind at every step of speech preparation and presentation: (3 Ws. Whom, What and How) a. To whom am I speaking? b. What do I want them to know, believe, or do as a result of my speech? c. What is the most effective way of composing and presenting my speech to accomplish that aim? B. Create a bond with audience by emphasizing COMMON d. value, e. goals f. experiences 2. Your Classmate as an Audience: a. Don’t take classroom as an artificial speaking situation. b. It is a testing ground, and learning opportunity. c. Take your classmates seriously and they are worthy your efforts. 3. The Psychology of Audience: a. Every speech contain two messages i. One sent by speaker ii. One received by the listener 1. We are dealing with “EGOCETRISM”—the tendency of people to be concerned above all with their own values, believes, and well-being. 2. It means that your listeners will hear and judge what you say. 3. It also means you must relate your message to your audience 4. Demographic Audience Analysis: a. Age (For example: Generation X, Y, baby boomers, Sr. citizen, each has its own value and experience.) b. Gender (Men, women have different value and belief. We should avoid gender-specific language (like chairman, chairperson… chapter 11 will talk about this more) c. Sexual Orientation d. Racial, Ethnic, and Cultural Background e. Religion f. Group Membership 5. Situation Audience Analysis: a. Size of the audience i. A size of 15 to 30 people is good for beginner. ii. The larger the audience, the more formal the speech must be. b. Physical Setting c. Disposition Toward the Topic i. Interest—assess audience interest in advance, and to adjust your speech accordingly ii. Knowledge---determine the level of your speech. iii. Attitude---it determine how you will handle your materials, not ignore or insult, but has to be more persuasive with hard evidence d. Disposition Toward the Speaker i. The more competent the listeners believe a speaker to be, the most likely they are to accept what the speaker says. ii. The more listeners believe that a speaker has their best interest at heart; the most likely they are to respond positively to the speaker’s message. e. Disposition Toward the Occasion i. Political speech—at Congress ii. Sermons—at church iii. After-dinner speech---after dinner 6. Getting Information About the Audience: a. Interviewing b. Questionnaires i. Fix-alternative questions (use yes or no to answer) ii. Scale questions (from very often to very seldom, from strong agree to strong disagree) iii. Open-ended questions (allow respondents to answer however they want, like “What is your opinion about….) 7. Adapting to the Audience a. Audience adaptation BEFORE the speech i. You have to step out of your own frame of reference and see things from other person’s point of view and assess how your audience is likely to respond to what you will say ii. Adjust what you say to make it as clear, appropriate, and convincing as possible. b. Audience adaptation DURING the speech Give the example on page 130. “I can see some of you are confused by my explanation. Let me try it again from another angle.” Chapter 6: Gathering Materials I. Rationale for Research *When we set out to give a public speech, we must show that we know what we are talking about! *If we are unsure of our facts, the listeners will quickly realize this, and the information being communicated will not be believed. People will not be interested in what you say. *Therefore, material must be gathered to make the communication believable, interesting, and valid. II. Three Ways of Gathering Material 1. Yourself You are knowledgeable about something, either due to a special interest in a topic (e.g., may be an expert about bicycles if you spend a lot of time putting together and fixing bicycles) or an experience (e.g., can describe the sights of Beijing if you have ever visited there). In this case, you can draw on your own knowledge to give an interesting, believable speech. Unfortunately, no one is an expert about everything. Sometimes you must give a speech about a subject you do not know. In that case, you must find information from those who are experts in a subject to put in your speech as you prepare the speech. This is called research. There are basic ways to research 2. Go Directly to the Source (Primary Research) If you know someone who is an expert in a subject you must talk about, go to the person. Arrange to meet that person and talk to that person about the subject you must talk about in your speech. This is called an “interview.” 3. Go to Reference Sources Written by or about Those Who are Experts about a Topic (Secondary Research) Sometimes we cannot meet the expert. The person lives too far away or is very important and does not have time to see you. In this case, you must look up books, magazines, newspapers, reference sources, and Internet sites that include what the expert has written or what others have written about the expert and the expert’s knowledge about the topic. This information can be used in your speech as quotes or paraphrases. This is the primary way material is gathered for a speech and for any formal written communication (theme paper, article, book, etc.) These materials are found in the library and on the Internet. Therefore, we will discuss this way of gathering material first. III. Doing Library Research 1. Sources of Information a. Librarian. There is always a person working in a library who will help you find the information you need. b. Catalogue. Before computers, this was a big piece of furniture with little drawers that contained cards listing every book the library had. In libraries with computers, you sit at a computer monitor and follow library instructions to bring up the catalogue electronically and find the book you need by author, title, or subject. c. Periodical Databases. This is the way you find popular magazines, scholarly journals, and newspapers (called “periodicals” because different versions of these materials are published over and over again; that is, “periodically.”) At the library computer, follow library instructions to find a listing of magazines, newspapers, and journals dealing with the information you need to know. Many databases include the entire article or a summary (abstract) of the article, so you do not have to find the hard copy of the periodical. You find what you want by using keywords. For example, if you want to know more about bicycles, you can type in “bicycle” to find periodicals with articles about bicycles. Sometimes, you may find thousands, so you will have to be more definite about your keywords. For example, use “bicycle repair” if you want to talk about how to fix a bicycle. Then you will not get a list of articles about “bicycle touring in China,” for example. d. Reference Works. This refers to encyclopedias, dictionaries, yearbooks, and atlases. These are usually found in books that you cannot take out of the library, although sometimes these works are listed in databases on the computer. The information you get from these materials is general; therefore, do not depend on these works for specific information. Use these works for a general overview of the subject you need to know. II. Internet Research World’s biggest library, usually with more recent information. Use “search engines” (Google, Alta Vista, Yahoo) or “metasearch engines” that are search engines of search engines (Dogpile, MetaCrawler) to find what you need. Make sure you find a “valid” site. Do not quote from sites that are simply advertising. Do not quote from home pages of individuals. Sites from universities are good. IV. Interviewing the Expert 1. Prepare a. Know the purpose of the interview b. Decide whom to interview (make sure they know about the topic about which you want information) c. Contact the person to interview and set up a time to talk to that person (can be done face to face, by E mail, or by telephone) d. Prepare questions (do not ask simple questions you should already know; ask specific detailed questions and make sure they are “open ended”; that is, not “yes or no”) 2. During the Interview a. Be “professional” (that is, dress appropriately, be on time) b. Be friendly. Do not argue with the person you are interviewing even if you don’t agree with the answers. c. Take notes and bring a tape recorder that you know how to operate, but ask if the interview can be taped. If the expert says no, do not tape but take good notes. d. Be attentive. Listen carefully to answers. Sometimes more questions will need to be asked to clarify previous answers. e. End the interview at the agreed-on time. Don’t go on and on. Many people like to talk and will make your interviewing easier, but, after an hour, most people are tired and want to get up and move around. 3. After the Interview a. Transcribe your notes (that is, rewrite in a more readable style that you can refer to later and still understand) your notes as soon as you can while the memory of the interview is still fresh in your mind. b. If you were able to record, review the tape. c. Courtesy: Send a letter to the person you interviewed thanking them for spending time with you. V. Final Comments a. Start researching early. Do not try to rush through it when time is running out. b. Realize that as you write your speech using your new-found information, you may realize that some information is no longer needed. That is OK. c. You may also find that you need to gather more specific material for information that you need to know as you are preparing the speech. Research is ongoing; it may require many visits to the library before you have all the information you need for an interesting, effective valid speech. Chapter 7 – Supporting Your Ideas I. Supporting Ideas and Critical Thinking Decide what ideas need to supported based on your audience, topic and purpose. Basic kinds of supporting evidence: II. a. examples b. statistics c. testimony Examples A. Brief Examples 1. Referred to in a passage to illustrate a point. 2. Can introduce a topic 3. Pile them one after the other to create a strong impression. B. Extended Examples - Narratives or anecdotes which pull the listener into the story. Hypothetical Examples – describing an imaginary situation. C. 1. D. Usually brief stories that relate a general principle Tips for Using Examples 1. Clarify unfamiliar and complex ideas 2. Reinforce ideas – make sure example is representative 3. Personalize ideas – add human interest 4. Make examples vivid – details to create a complete picture for maximum impact 5. Practice delivery a. Not rushed b. Use eye contact III. Statistics Purpose is to create an overall impact on listeners Often cited in passing to strengthen or clarify a point. Like examples can be stacked to show seriousness of an issue A. Understanding Statistics 1. Are they representative – is the sample size big enough to generalize from? 2. Are statistical measures used correctly to represent the information you intend? a. Mean – average value of a group of members b. Median – middle number in a group of numbers arranged from highest to lowest c. Mode – the number that occurs most frequently in a group of numbers 3. Are the sources reliable for unbiased numbers? B. Tips for Using Statistics 1. Use them to quantify ideas – numerical precision. 2. Use them sparingly – too many stats become difficult to grasp and boring for an audience. 3. Use them for most important points. 4. Identify the sources 5. Explain the statistics – they need to be interpreted to make them meaningful to the audience 6. Round off complicated stats – easier to comprehend 7. Use visual aids to clarify statistical trends – graphs and charts C. Where to find Statistics: 1. Statistical Yearbook (by the U.N.) 2. Statistical Abstract of the U.S. – www.census.gov/statab/www 3. Guinness Book of World Records (for more esoteric info) IV. Testimony Quotations or paraphrases used to support a point. A. Expert Testimony: from people who are recognized experts in their fields. Lends credibility. B. Peer Testimony: from ordinary people with firsthand experience or insight on a topic. C. Quoting vs. Paraphrasing 1. Paraphrasing – presenting the main idea of a quote in your own words. Use a paraphrase when: a. The wording of a quote is obscure or awkward b. When the quotation is longer than two or three sentences 2. Use Quotations when: a. They are brief b. They convey your meaning better than you can c. They are eloquent, witty or compelling D. Tips for Using Testimony 1. Quote or Paraphrase accurately a. Don’t misquote b. Don’t change the meaning of the statements when paraphrasing c. Don’t take the quote out of context i. Removing the statement from the words or phrases surrounding it. ii. Thereby changing someone’s intended meaning 2. Use Testimony from Qualified Sources a. Qualified on the subject at hand b. Not celebrity testimonials (unless it is a subject upon which they are experts or have firsthand experience) 3. Use Testimony from Unbiased Sources a. ELENA’S NOTE: this point may not always be relevant. It depends on the situation. i. e.g. – a source who has tested a new product or scientific theory should definitely be unbiased. ii. e.g. – a source who is representing a particular point of view will necessarily not be unbiased 4. Identify the People Quoted or Paraphrased a. Full name and qualifications the first time a person is quoted or paraphrased. b. ELENA’S NOTE: This is necessary for credibility and for legal reasons. 5. Sources of Testimony a. Books b. Journals c. Specific experts in a field i. e.g. Faculty members, board members, researchers, professionals, etc. Chapter 14: Speaking to Inform This chapter addresses the important characteristics of presentations that are specifically geared to giving information and how to effectively organize the presentations. The chapter reiterated three important points presented in an earlier chapter: These are 1) limiting a speech to two to five main points 2) keep the main points separate 3) try to use the same pattern of wording for each main point and 4) balance the amount of time for each main point. The speaker giving the speech needs to understand what is fascinating to her may not necessarily be fascinating to everybody and that her job is make the speech interesting and meaningful to the audience. A speech that gives information needs to have these characteristics to be successful: 1. Information must be presented accurately. 2. Information must be presented clearly so the audience understands. 3. The presenter must engage the audience, to keep their interest. Four Major Types of Speeches that are geared to Inform 1. A speech that talks about visible, tangible and stable objects (e.g. specific people; trains, comic strips, the U.S. army) 2. A speech about processes (e.g. how to set a table; how to put a resume together; how hurricanes develop; how rugs are made 3. A speech about events ( anything that happens or is regarded as a happening) – e.g. Holocaust; civil rights movement, Battle of Little Big Horn, mountain climbing) 4. [the most difficult kind of speech] A speech about concepts – typically things that are abstract like ideas, principles, beliefs, theories (e.g. Confucianism, religious beliefs, theories of psychology) Process for organizing the speech 1. Develop a Purpose statement for the speech in order to focus on one aspect of the topic or subject. Doing this avoids taking on a subject that is too broad or too general especially when there are time constraints. Examples: a) to inform my audience about the major achievements of Frederick Douglas; b) To inform my audience of the major steps in the classic Japanese tea ceremony; c) To inform my audience about why so many lives were lost when the Titanic sank 2. Identify the Central Idea Examples: a) Frederick Douglas became one of the greatest figures in American history even though he was born into slavery. b) There are five major steps in the classic Japanese tea ceremony c) Inability to remove passengers and crew from the Titantic caused 2/3rds of those on board to die 3. Organize the main points (depending on the topic – the points could be presented chronologically, presented in spatial order, or topically) Examples: a) Spatial – Northwest Ohio is largely farmland; Northeast is largely industrial; Southwest Ohio has a service economy; Southeast is much like the Northwest and Central Ohio is a combination of farmland, industrial and service economy. b) Topical – cars can be powered by electricity; cars can be powered by a mix of electricity and gas; cars can be powered by hydrogen c) Chronological – self explanatory Important points: 1. Always try to group multiple points (especially when there are many main points) to make it easier to understand and remember. To the extent possible, always try to limit the number of points so that the audience is not overwhelmed. 2. Visual aids are very important for informative speeches 3. Students should not confuse topics that are suitable for speeches geared to sharing information vs. topics that are suitable for speeches meant to persuade. Guidelines for informative speaking to keep in mind 1. Don’t overestimate what the audience knows. This is a common tendency for the person making the speech. 2. Relate the subject directly to the audience. This helps to engage the audience and keep their interest. Nothing interests people more than themselves. With this in mind, try to put your listeners into the body of the speech. 3. Don’t be too technical or use too much jargon. Keep it simple so that the average person can understand. 4. Avoid abstractions. This can be done using description or words that compare and contrast. Chapter 15: Speaking to Persuade I. Three Things to Keep in Mind a. Of all the kinds of public speaking, persuasion is the most complex and the most challenging. b. Persuasive speaking occurs in a hostile environment where listeners try to find every reason not to agree with you. c. So you must think of your persuasive speech as a kind of mental dialogue with your audience in which you must anticipate possible objections from your audience and then answer those objections. No matter how expert you are on the topic, no matter how skillfully you prepare the speech, no matter how captivating your delivery is, some listeners will not agree with you. II. So it requires considerably more research and preparation time than does the informative speech. So you need to define your target audience, i.e. a particular part of the whole audience that you want to reach with your speech. Three Types of Persuasive Speech a. Persuasive Speeches on Questions of Fact: Unlike informative speeches, whose aim is to give information as impartially as possible, persuasive speeches on questions of fact present one view of the facts as persuasively as possible (e.g. persuading the audience that genetically engineered crops pose serious dangers to the environment and to human health). b. Persuasive Speeches on Questions of Value: In this type of persuasive speech, you must first establish the standards for your value judgment and then apply those standards to the subject of your speech (e.g. if your argument is bicycle riding is the ideal form of land transportation, you first need to identify the standards for an ideal form of land transportation and then show how biking measures up against those standards). c. III. Persuasive Speeches on Questions of Policy: Questions of policy inevitably involve questions of fact and may also involve questions of value. What separates persuasive speeches on questions of policy from the other two is that they call for specific courses of action from the audience. Three basic issues when discussing a question of policy – (1) need, i.e. is there a serious problem that requires a change from current policy?; (2) plan, i.e. do I have a plan to solve the problem?; and (3) practicality, i.e. will my plan solve the problem without creating new ones? Organizing speeches on questions of policy – (1) problem-solution order, (2) problem-cause-solution order, (3) comparative advantages order, and (4) Monroe’s motivated sequence. Five Steps in Monroe’s Motivated Sequence Introduction a. Attention: Gain the attention of your audience by telling a dramatic story, making a startling statement, posing a question, or arousing curiosity or suspense. Body b. Need: State the problem with the existing situation and illustrate it with strong supporting materials, such as statistics, examples, and testimony. c. Satisfaction: Present your plan / solution to the problem and show how it will work. d. Visualization: Show how the audience will profit from your policy by listing specific benefits. Conclusion e. Action: Say exactly what you want the audience to do and how to do it. Then conclude with a final stirring appeal that reinforces their commitment to act.