Lesson Plans October 11--14 English 10 Purpose: students will work

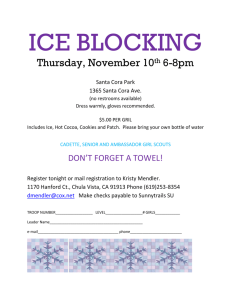

advertisement

Lesson Plans October 11--14 English 10 Purpose: students will work collaboratively, in small groups, to create media presentations on either a thematic, character, tone, comparison w/other piece/s of literature or historical background for the Langston Hughes short story “Cora Unashamed.” Teacher Students Continue lesson in progress -- mini research project -- on CORA UNASHAMED. Students will work on project two days this week. Students will continue working on media presentation for topic they chose on CORA UNASHAMED. By the end of this week students should be ready to present during the first Bell 3 will start project and finish in a week in 2nd quarter. week and a half. Students will spend some time looking at scoring rubric for the project. Assignments and handouts are attached to this lesson plan. Scoring rubric is also attached. 1 different from watching the movie? What are the advantages and disadvantages of each medium? RESEARCH TOPIC/ASSIGNMENTS FOR “Cora Unashamed” After Viewing 1. In a class or small-group discussion, compare and contrast the story and the film. Discuss the similarities and differences between characters, tone, and setting. Why do you think the filmmakers chose to change certain things? What do you think of their choices? 2. Discuss the title of the story. What are some of the things about which Cora is unashamed? Why? Who else in the story is unashamed? Who's ashamed? What do you think Langston Hughes is trying to say about shame? 3. When Josephine is born at the start of the film, Cora's mother says, "Ain't no good come out of white and colored love." How is this statement supported and/or challenged by what happens in the film? 4. Examine the relationships in the film. Discuss Cora's relationship with Joe, with Jessie, with Mrs. Studevant, and with Mr. Studevant. How is race a factor in each one? Is it irrelevant in any way? Compare and contrast the "couples" in the film (Cora and Joe, Jessie and Willie, and Mr. and Mrs. Studevant). How does race and/or class affect each of these relationships? 5. Discuss what happens to Willie and his family. How is their situation similar to Cora's? How do you think the experience of immigrants to the United States is similar to the experience of African Americans? How is it different? 6. Ask students to compare and contrast literature and film using examples from Cora Unashamed and other film adaptations (either in an essay or discussion). How is reading the story 7. Have students think about a personal relationship or situation in which race or class was or is a factor. Ask them to write about the relationship/situation and how it was or is impacted by race or class. How might the relationship or situation have been different in Cora's time? 8. Assign small groups one or two other stories in Langston Hughes's short story collection, The Ways of White Folks. After reading the story, have groups discuss how black and white worlds collide in each narrative. How does each group view the other and why? How do the relationships in the story create tension? Ask each group to present a summary of their story and discussion to the rest of the class. To extend the activity, students can also do research projects on how black and white worlds mix today (one suggested resource is the New York Times' 15-part series, "How Race Is Lived in America.") http://www.google.com/search?q=How+Race +is+lived+in+America++NYT&sourceid=ie7&rl s=com.microsoft:en-us:IESearchBox&ie=&oe= 9. Have students look at the Harlem Renaissance (http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/master piece/americancollection/cora/harle m.html) section to identify other artists from the era. Ask them to choose a work by one of these artists (e.g., a song, painting, poem, novel, or short story). In an essay, have them compare and contrast the work with "Cora Unashamed." Have them address the differences and similarities between the works' subjects, themes, characters, and style. How were these works 2 important to their era? How are they still important today? 10. Have the class read Professor Phyllis Palmer's article, Race, Sex, and Housework in the 1930s. How do students think Cora and Mrs. Studevant are different from domestics and their employers today? Consider having students debate the role of domestic help in our culture using examples from Cora, Palmer's article, and personal experiences. 11. Using the Langston Hughes timeline and other resources, have students research the life of the author. Have students read his poem "I, Too" and/or other poetry, fiction, and nonfiction by the author. For a collection of the author's poetry (including "I, Too"), see Vintage Classics' Selected Poems of Langston Hughes. Discuss how the author's life and times are reflected in his writing. What makes his work uniquely African American? What makes it uniquely American? I, Too by Langston Hughes I, too, sing America I am the darker brother. They send me to eat in the kitchen When company comes, But I laugh And eat well, And grow strong. Tomorrow, I'll be at the table When company comes. Nobody'll dare Say to me, "Eat in the kitchen," Then. Besides, They'll see how beautiful I am And be ashamed -I too, am America Cora Unashamed: Race, Sex and Housework in the 1930s by Phyllis Palmer Professor of American Studies and Women's Studies, The George Washington University At first glance, Cora Unashamed, the premiere film of Masterpiece Theatre's American Collection, has a familiar look. African American maid Cora Jenkins (Regina Taylor) works for a demanding white family, headed by socialite Mrs. Art Studevant (Cherry Jones). In addition to handling all the domestic chores, Cora is in charge of, and develops a loving relationship with, the youngest Studevant child, Jessie (Ellen Muth). Cora's race and sex disqualify her from social equality with her employers, but tragedy reveals her to be their moral superior. But there's a twist to this tale. Langston Hughes's short story of the same name, "Cora Unashamed," is told from the black perspective, a novel approach to storytelling at the time of its publication in 1934. Hughes made use of stock characters familiar to black and white audiences, but transformed them. Hughes's short story collection, The Ways of White Folks, in which "Cora Unashamed" first appeared, was revelatory for its presentation of reality as experienced by black protagonists. During the 1930s, through the wildly popular, still relatively new, medium of film, Hollywood entertained audiences with set images of black Americans. While white characters could inhabit many walks of life, blacks were generally cast as servants, entertainers, or comic foils. The movies certainly didn't invent these images; they merely picked up where literature left off, drawing on the same stereotypes that authors and performers had used for decades. It seemed Hughes, on first read, was no different. He filled his story with details that would reassure white readers of its accuracy and truth. Here was Cora, a black maid for a socially superior white family, the Studevants. Their moral superiority was guaranteed as well: Cora had given birth to a child out of wedlock. Furthermore, in accord with the popular expectations of the period, Cora's devotion to her employers' white child appeared to be boundless. But Hughes was not interested in telling a story that white authors had been telling for years. Instead, he subverted the presumed relationship of white (flawless) protagonists and their black (flawed) foils. Seen from the servant's perspective, all this information takes on a different meaning and transforms the typical popular image of superior whites being served by inferior blacks. While Cora Jenkins is a servant -- and the lowliest social creature on the white scale at that, the domestic, or maid -- she is neither childlike nor unthinking, as black servants were so often depicted in film and literature of the time. Cora's point of view, candid and courageous, reveals more about the truths of life in the Studevant household than her white, middle-class employers would wish to acknowledge, even to themselves. Melton, Iowa, the setting of the story, is "one of those miserable in-between little places, not large enough to be a town, nor small enough to be a village -- that is, a village in the rural, charming sense of the word." The Jenkins family -Cora's parents, siblings, and Cora herself -- are socially and economically isolated, the only black family in town. The role that Cora plays later in the story, in the Studevant home, is not unlike the one she plays in her own, except that "she ate better" with the Studevants. The eldest of eight children, Cora was essentially a maid for her family: "She always had a little brother, or a little sister in her arms," Hughes explains. An ailing mother and alcoholic father do not provide much stability for the family, and in the eighth grade, Cora quits school to work for the well-to-do white Studevants. Once again, in keeping with prevalent popular-culture images, Cora is quiet and obedient -- "humble," Hughes calls her. Cora's humility, however, doesn't derive from some native subservience, but from the calculations of self-preservation. 3 To complain to her employers, who treat her badly but not too badly, would be to risk having to work for "poorer white folks who would treat her worse," or to be out of work entirely. And to be out of work entirely is not an option for Cora, for she supports her family. Opportunity comes to Cora, as it did to many non-white women at the time, in the form of the "maid of all work" job. According to popular magazines and household manuals of the '30s, middle-class white householders relied on the maid of all work to handle not only the physically hardest tasks (except window-cleaning, usually left to men), but often to work 18-hour days, with no breaks. Cora's workday mirrors real-life schedules reported by domestic workers to the U.S. Women's Bureau. One worker outlined her Saturday: Got up at 5:15, fixed furnace, got breakfast, made beds, polished nickel in bathroom and kitchen, polished tub and other fixtures; took floor brush, scrubbed and polished tile floor in bathroom, scrubbed and polished floor in kitchen, washed windows, wiped woodwork, scrubbed and polished steps to basement and washed banisters. Swept all walks and front porch, washed silk stocking, went to grocery, helped make peanut bread; trimmed dried beef, washed vegetables, put things away, scrubbed eggs, cut up vegetables to put in soup, fixed supper, made salad and desert. Washed dishes. To Cora the litany of demands is a never-ending refrain: "Cora, come here... Cora, put... Cora... Cora... Cora! Cora!" There seems no limit to Mrs. Studevant's demands on Cora's time. Once again, Hughes's Cora shares much with "real" women of her social standing, or lack thereof. Especially for women of color, who were limited by racial discrimination and who constituted the majority of domestic workers as early as 1920, domestic employment ranked as a major occupation. By the '20s, many white women had obtained more "respectable" jobs in retail sales, offices, or factories. By contrast, the 1930 Census revealed that domestic work was a primary occupation for African American, Mexican American, Japanese American, and Native American women. Working conditions and wages were often disputed. But under Franklin Roosevelt, Depression and New Deal policies brought about enormous improvements for American workers as the government responded to labor union demands for shorter hours and better wages. By 1938 the Fair Labor Standards Act set a federal floor for minimum wages and a ceiling for hours for all workers in businesses that fell under Congress's regulatory purview of interstate commerce. Throughout the debates leading to the legislation, domestic workers sought inclusion as workers comparable to anyone in a factory, store, or business. Congress, however, continued to exclude them from hour and wage coverage. Only in the aftermath of Civil Rights and during the Women's Movement in the 1970s did domestic workers gain hours and wages and Social Security coverage. Hughes never veers into such overtly political territory, though, and Cora doesn't benefit from such regulations. Ironically, Mrs. Studevant's prominence depends very much on Cora's efficient housework and child care. Hughes imbues Mrs. Studevant with all the qualities an upstanding lady needed. She is "the civic and social leader of Melton, president of the Woman's Club three years straight, and one of the pillars of the church." The white middle-class housewife's status derived from her presumed moral virtue and her valuable community and charity work -- not to mention her clean home. Cora is not merely an extension of the wife's work, as domestic work was often categorized; she is actually the source of cleanliness and, for Jessie, comfort in the Studevant home. Hughes describes this white, middle-class reliance on women domestics accurately. A Fortune magazine survey late in the 1930s reported that "70% of the rich, 42% of the upper middle class, and 14% of the lower middle class" hired domestic workers. In addition, my own research into mid1930s family spending shows that the wife's educational level correlated with the hiring of domestic servants. Women with more education and greater possibilities of paid or volunteer employment regularly hired less well-educated women, and usually those with options limited by racial discrimination, to take over housework. Because middle-class educated women gained reputation outside the home only if they also kept their homes immaculate and their children well dressed and well fed, their achievements depended directly on the availability and competence of unheralded domestic workers. Rearing children was considered part of running the home. "Like all the unpleasant things in the house," Hughes explains, "Jessie was left to Cora." Jessie does not fit into the idealized world that Mrs. Studevant, with Cora's behind-the-scenes help, so carefully cultivates. In developing the relationship between Cora and Jessie, Hughes undercuts the popular ideal, epitomized in Shirley Temple movies, that white, well-dressed, mannerly children were so beautiful and superior that any servant would prefer these "angels" to her own children. Instead, Cora fills the gap left by her own daughter's early death with love for Jessie, who has been emotionally abandoned by her parents and siblings. Cora needs someone to love, and Jessie needs someone to love her. Their relationship is grounded in the similarity of their characters and circumstances, not in Cora's putting a higher value on a white child than a black one. And it is love. Cora bathes and clothes the little white baby -and perhaps more importantly, keeps her in the kitchen out of her mother's sight. Having given birth to her own daughter at the same time, Cora nurses Jessie, too, on Mrs. Studevant's instructions, even though when the unmarried Cora's pregnancy had begun to show, Mrs. Studevant banished her from the Studevants' "proper" home. A callous mother, Mrs. Studevant despairs of "dull little Jessie," who hasn't the wit and talent to follow her mother's social lead. Concerned above all with her social position, Mrs. Studevant leaves Jessie to Cora's care and teaching, where Jessie thrives. Cora knows that only the social aspects of intimate relationships are bound by race. Her relationship with Jessie is indicative of this: "In her heart," Hughes writes, "she had adopted [Jessie]." In her heart, perhaps, but Cora was, of course, forbidden to make any decisions regarding the girl's welfare. Similarly, not sex, but marriage, adheres to racial barriers. The father of Cora's only child, Josephine, is white. "[Cora] had never known a colored lover," Hughes wrote. "There weren't any around. That was not her fault." She knows that even after pregnancy, marriage is not an option. "[S]he hadn't expected to marry Joe, or keep him. He was of that other world... But the child was hers -- a living bridge between two worlds." 4 While Cora may view Josephine as a bridge between black and white, the child's very existence marked Cora as "immoral." Popular-culture movie models, for instance, encouraged women to be sexy but not "loose." Girls learned to attract men coyly, to allow a bit of "petting," but always to keep them at an elegantly gloved arm's length. Katharine Hepburn, Myrna Loy, and Ginger Rogers were stars who, on the big screen, dressed in fashionably revealing clothes, yet never had sexual relations, or even serious kisses, except with their husbands -and sometimes not even with them. In her simple honesty, Cora has had sex with a man who shows her affection and kindness, she accepts her pregnancy, and she devotes love to her baby. Much as Cora enters into a relationship that can never reach the "proper" conclusion of marriage, Jessie chooses a boyfriend -- and a future -- socially suspect because of his dark, Greek complexion. According to Hughes's biographer, Arnold Rampersad, Sherwood Anderson remarked in a review of The Ways of White Folks: "My hat is off to you in relation to your own race,' but not in relation to the whites, who were caricatures." Anderson may have had a point that Hughes was not particularly interested in presenting a white point of view; after all, that viewpoint dominated the media of the era. Despite the fact that the behavior Hughes depicts is accurate and backed up by research, it's true that Mrs. Studevant is largely a caricature. But the same could be said for Cora's father (not portrayed in the dramatization), who "passed the evenings telling long, comical stories to the white riff-raff of the town, and drinking licker." Even as he indulged some popular stereotypes, Hughes was rewriting an unbalanced cultural picture. He created a heroine unashamed of her work and of her sexuality. In doing so, he provided a liberating vision of womanhood for all women. Phyllis Palmer, a Professor of American Studies and Women's Studies at The George Washington University, is the author of Domesticity and Dirt: Housewives and Domestic Servants in the United States, 1920-1945 (1990) and other articles and essays about domestic workers and housework. The Well-Appointed House A gem of a house may be no size at all, but its lines are honest, and its painting and window curtains in good taste. As for its upkeep, its path or sidewalk is beautifully neat, steps scrubbed, brasses polished, and its bell answered promptly by a trim maid with a low voice and quiet courteous manner; all of which contributes to the impression of "quality" even though it in nothing suggests the luxury of a palace whose opened bronze door reveals a row of powdered footmen. children whose whole lives are influenced by her example, especially where busy parents give only a small portion of time to their children. From Etiquette, by Emily Post, 1922 Madam and Her Madam by Langston Hughes from The Selected Poems of Langston Hughes I worked for a woman, She wasn't mean-But she had a twelve-room House to clean. Had to get breakfast, Dinner, and Supper, too-Then take care of her children When I got through. Wash, iron, and scrub, Walk the dog around-It was too much, Nearly broke me down. I said, Madam, Can it be You trying to make a Pack-horse out of me? She opened her mouth. She cried, Oh, no! You know, Alberta, I love you so! I said, Madam, That may be true-But I'll be dogged If I love you! The Nurse...It is unnecessary to add that one can not be too particular in asking for a nurse's reference and in never failing to get a personal one from the lady she is leaving. Not only is it necessary to have a sweet--tempered, competent and clean person, but her moral character is of utmost importance, since she is to be the constant and inseparable companion of the 5 And Poland's plain, and England's grassy lea, And torn from Black Africa's strand I came To build a "homeland of the free." Let America Be America Again by Langston Hughes Let America be America again. Let it be the dream it used to be. Let it be the pioneer on the plain Seeking a home where he himself is free. (America never was America to me.) Let America be the dream the dreamers dreamed-Let it be that great strong land of love Where never kings connive nor tyrants scheme That any man be crushed by one above. (It never was America to me.) O, let my land be a land where Liberty Is crowned with no false patriotic wreath, But opportunity is real, and life is free, Equality is in the air we breathe. (There's never been equality for me, Nor freedom in this "homeland of the free.") Say, who are you that mumbles in the dark? And who are you that draws your veil across the stars? I am the poor white, fooled and pushed apart, I am the Negro bearing slavery's scars. I am the red man driven from the land, I am the immigrant clutching the hope I seek-And finding only the same old stupid plan Of dog eat dog, of mighty crush the weak. I am the young man, full of strength and hope, Tangled in that ancient endless chain Of profit, power, gain, of grab the land! Of grab the gold! Of grab the ways of satisfying need! Of work the men! Of take the pay! Of owning everything for one's own greed! The free? Who said the free? Not me? Surely not me? The millions on relief today? The millions shot down when we strike? The millions who have nothing for our pay? For all the dreams we've dreamed And all the songs we've sung And all the hopes we've held And all the flags we've hung, The millions who have nothing for our pay-Except the dream that's almost dead today. O, let America be America again-The land that never has been yet-And yet must be--the land where every man is free. The land that's mine--the poor man's, Indian's, Negro's, ME-Who made America, Whose sweat and blood, whose faith and pain, Whose hand at the foundry, whose plow in the rain, Must bring back our mighty dream again. Sure, call me any ugly name you choose-The steel of freedom does not stain. From those who live like leeches on the people's lives, We must take back our land again, America! O, yes, I say it plain, America never was America to me, And yet I swear this oath-America will be! Out of the rack and ruin of our gangster death, The rape and rot of graft, and stealth, and lies, We, the people, must redeem The land, the mines, the plants, the rivers. The mountains and the endless plain-All, all the stretch of these great green states-And make America again! I am the farmer, bondsman to the soil. I am the worker sold to the machine. I am the Negro, servant to you all. I am the people, humble, hungry, mean-Hungry yet today despite the dream. Beaten yet today--O, Pioneers! I am the man who never got ahead, The poorest worker bartered through the years. Yet I'm the one who dreamt our basic dream In the Old World while still a serf of kings, Who dreamt a dream so strong, so brave, so true, That even yet its mighty daring sings In every brick and stone, in every furrow turned That's made America the land it has become. O, I'm the man who sailed those early seas In search of what I meant to be my home-For I'm the one who left dark Ireland's shore, 6 7