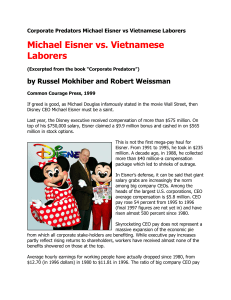

"What pay for performance looks like: the case of Michael Eisner"

advertisement

"What pay for performance looks like: the case of Michael Eisner" By Stephen F. O’Byrne, Stern Stewart & Co. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 5 (summer 1992), pp. 135-136 It’s easy to think of Disney CEO Michael Eisner as a classic case of executive pay run amok. His total compensation in his first six years on the job exceeded $250 million. In reality, he is a classic example of what “pay for performance” looks like. When Eisner was hired in late 1984, he took over a troubled company. Disney had just been through a bitter takeover battle, theme park attendance was declining, and return on equity had fallen below 8%. When he joined Disney, Eisner agreed to a six-year employment contract with three main compensation provisions: a base salary fixed at $750,000, an annual bonus equal to 2% of Disney’s net income in excess of 9% of stockholders’ equity, and a tenyear option on two million shares exercisable at Disney’s current market price of $14. While Eisner’s contract provided for guaranteed payments with a present value of only $3.9 million, its expected value was, of course, much greater. The expected value of his options, based on the Black-Scholes option pricing model, was $16 million. I also estimate that the expected value of his total contract, including bonus and pension rights, was $22 million. The Disney directors were presumably willing to enter into a contract worth $22 million because it provided a tremendous performance incentive that could provide great benefits to Disney shareholders. The contract made Eisner’s wealth even more sensitive to Disney performance than the shareholders’ wealth. A 200% increase in Disney’s stock value – above the company’s CAPM-expected return – would increase the value of Eisner’s contract by 279%. A 67% decline in Disney’s shareholders’ wealth would reduce the value of Eisner’s contract by 71%. What happened? Eisner and his team took risks, transformed the company in many ways and achieved remarkable success. (The Disney Touch by Ron Grover provides a fascinating chronicle of Eisner’s tenure.) By the end of the original contract term, the price of Disney stock had increased to $102 per share, an increase of more than 600%. Over that same period, Eisner’s compensation (including unrealized option gains) from his original contract was $190 million, an increase of more than 750% over the initial contract value. The shareholder gain from Eisner’s performance was enormous. The wealth of Disney shareholders had increased from $1.9 billion in 1984 to more than $14 billion at the end of 1990, a gain of $9.5 billion more than they would have realized with an investment in the S&P 500. The cost of Eisner’s performance incentive was about 2% of the excess return realized by Disney shareholders. In late 1988, Eisner signed a new ten-year employment contract. The contract extension presented Disney with a difficult choice. Should the key terms of the contract – a bonus of 2% of net income in excess of 9% of equity and an option on two million shares exercisable at the current market price – be extended even though they now had an expected 135 value of more than $120 million, far in excess of competitive pay levels? Or should the bonus formula be changed and the option grant reduced to bring the contract value closer to competitive levels even though doing so would be to penalize Eisner for his own superior performance? If Disney penalize Eisner for superior performance, it would be undermining the strong performance incentive it originally sought to create and that served it so well. Disney made the right decisions. The company chose to maintain the integrity of Eisner’s performance incentive at the cost of paying far above the market. Disney and Eisner agreed to extend the original contract terms (including the $750,000 salary) with three modest changes: increasing the bonus threshold to 11% beginning in 1991, paying the portion of the bonus attributable to net income in excess of 17.5% of equity in restricted stock (also beginning in 1991) and making a quarter of the two million new option shares exercisable at $10 above the current market price of $69. By the end of 1990, Eisner had an unrealized gain of $60 million on the new option grant, in addition to the $190 million in compensation he received under the terms of his original contract. Eisner’s contract is very different from the typical CEO’s compensation program. The typical CEO has much more guaranteed pay. Salary and pension on salary represent 38% of the typical CEO’s total company-related wealth vs. 18% of Eisner’s contract in 1984. The typical CEO has a bonus plan that shows little performance sensitivity over time because targets are adjusted to the level of recent performance. The typical CEO receives annual long-term incentive grants (often including restricted stock) with “fixed value” grant guidelines that penalize performance instead of the front-loaded options that Eisner received. “Fixed value” grant guidelines guarantee the same dollar grant regardless of stock price performance. Superior stock price performance is effectively penalized by reducing the number of shares granted and poor stock price performance is rewarded by increasing the number of shares granted. “Fixed value” restricted stock grants are particularly pernicious since they ensure large gains for poor performance. The net result is that the typical CEO has a much weaker performance incentive than Michael Eisner. A 200% increase in shareholder wealth would increase the typical CEO’s companyrelated wealth by only 91% – far less than the 279% change in Eisner’s wealth for the same performance. A 67% decline in shareholder wealth would decrease the typical CEO’s companyrelated wealth by only 30%, as compared to the 71% decline in Eisner’s wealth for the same performance. One lesson of Michael Eisner is that true pay for performance will – and should – lead to very high pay levels. A second lesson is that the average CEO’s total compensation program needs a lot more performance incentive to fully align the CEO’s interests with those of the shareholders. 136