Gleason J. B. The Development of Language M L U As children get

advertisement

Gleason J. B.

The Development of Language

MLU

As children get older, their sentences grow longer. Recent studies of large numbers of children have

provided excellent normative data on the age at which English-speaking children make the transition to combining

words and using simple sentences. These data come from a set of parental report measures called the

Communicative Development Inventories, which provide highly reliable information about children's language

abilities at the early stages. There is wide variability in the onset of combinatorial language. Some children begin as

early as fifteen months, the average seems to be at about eighteen months, and by the age of two almost all children

are producing some word combinations. While age itself is not a good predictor of language development since

children develop at vastly different rates, the length of a child's sentences is an excellent indicator of syntactic

development; each new element of syntactic knowledge adds length to a child's utterances. Roger Brown (1973)

introduced the major measure of syntactic development, the mean length of utterance or MLU, which is based on

the average length of a child's sentences scored on transcripts of spontaneous speech. Length is determined by the

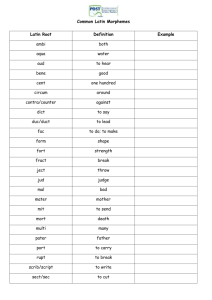

number of meaningful units, or morphemes, rather than words. Morphemes include simple content words such as

cat, play, do, red; function words such as no, the, you, this; and affixes or grammatical inflections such as un-, -s, ed. The addition of each morpheme (or minimal unit carrying meaning) reflects the acquisition of new linguistic

knowledge. So children who have similar MLUs are at the same level of linguistic maturity, and their language is at

the same level of complexity.

In order to calculate the MLU of a particular child, one needs a transcript of a half-hour conversation. The

child's language must be divided into separate utterances, and these utterances must be divided into morphemes.

Brown (1973) provides detailed rules for judging what constitutes a morpheme for the child learning English (see

Figure 5.4). For example, although compound words like birthday or goodnight contain two morphemes, they only

count as one. The same is true for diminutives (e.g., doggie, ducky) and irregular past tense verbs (e.g., got, did).

On the other hand, inflections (e.g., regular past tense -ed, plural -s, progressive -ing) and auxiliaries (e.g., is, have,

will) count as separate morphemes. The number of morphemes in each of the first 100 fully transcribed utterances

is counted, and the total is then divided by 100 (see Figure 1).

1. Start with the second page of the transcription unless that page involves a recitation of some kind. In this latter

case, start with the first recitation-free stretch. Count the first 100 utterances satisfying the following rules.

2. Only fully transcribed utterances are used; none with blanks. Portions of utterances, entered in parentheses to

indicate doubtful transcription, are used.

3. Include all exact utterance repetitions (marked with a plus sign in records). Stuttering is marked as repeated

efforts at a single word; count the word once in the most complete form produced. In the few cases where a word is

produced for emphasis or the like (no, no, no) count each occurrence.

4. Do not count such fillers as mm or oh, but do count no, yeah, and hi.

5. All compound words (two or more free morphemes), proper names, and ritualized reduplications count as single

words. Examples: birthday, rackety-boom, choo-choo, quack-quack, night-night, pocketbook, see saw. Justification

is that no evidence that the constituent morphemes function as such for these children.

6. Count as one morpheme all irregular pasts of the verb (got, did, went, saw). Justification is that there is no

evidence that the child relates these to present forms.

7. Count as one morpheme all diminutives (doggie, mommie) because these children at least do not seem to use the

suffix productively. Diminutives are the standard forms used by the child.

8. Count as separate morphemes all auxiliaries (is, have, will, can, must, would). Also all catenatives: gonna,

wanna, hafta. These latter counted as single morphemes rather than as going to or want to because evidence is that

they function so for the children. Count as separate morphemes all inflections, for example, possessive {s}, plural

{s}, third person singular {s}, regular past {d}, progressive {in}.

9. The range count follows the above rules but is always calculated for the total transcription rather than for 100

utterances.

Figure 1. Rules for calculating mean length of utterance. (Reprinted by permission of the publishers from A First

Language by Roger Brown, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, Copyright 1973 by the President and

Fellows of Harvard College.)

In longitudinal studies, the MLUs calculated at successive points in time gradually increase. Figure 2

shows the MLU plotted against chronological age for the three children studied by Brown and his colleagues.

Clearly, MLU grows at different rates in different children. Of the children followed by Brown, Eve's MLU rose

most sharply, indicating very rapid language development, whereas Sarah and Adam showed more gradual and less

consistent increments in their MLU. According to the MLU norms developed by Miller and Chapman (1981),

based on a sample of over 100 middle-class children in Madison, Wisconsin (see Figure 3), Adam and Sarah are

about average for their age, whereas Eve is very much advanced for her age. Using the MLU, Brown subdivided

the major period of syntactic growth into five stages, beginning with Stage I when the MLU is between 1.0 and 2.0.

Successive stages are marked by increments of .5; thus, Stage II goes from 2.0 to 2.5, Stage HI is from 2.5 to 3.0,

Stage IV is from 3.0 to 3.5, and Stage V is from 3.5 to 4.0. Beyond an MLU of about 4.0 some of the assumptions

on which the measure is based are no longer valid, and longer sentences do not simply reflect what the child knows

about language; so MLU loses value as an index of language development after this stage.

Figure 2. Mean length of utterance and chronological age of three children. (Reprinted by permission of the

publishers from A First Language by R. Brown, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Copyright 1973 by the

President and Fellows of Harvard College.)

Figure 3. MLU norms. (From "The Relations between Age and Mean Length of Utterance" by J. F. Miller and R.

S. Chapman, 1981, Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 24, pp. 154—161. © American Speech-LanguageHearing Association. Reprinted by permission.)

There are some questions that arise in calculating MLUs in foreign languages, especially highly inflected

and synthetic languages such as German, Russian, or Hebrew. In these cases it becomes difficult to decide what

functions as a morpheme in the child's speech, and it is easy to obtain inflated numbers. Still, there have been

attempts to extend the concept of MLU to structurally varied languages or to modify the measure to account for

cross-linguistic differences. In some languages, calculating the length of utterances in words, rather than

morphemes, has proven to be quite useful. One example comes from a recent study on the acquisition of Irish. It

remains to be seen how well this or some other related measure would apply to other languages. By using a similar

index to chart language growth across a range of languages, we can search for the universal and invariant features

that characterize the main stages of syntactic development. (...)