File

advertisement

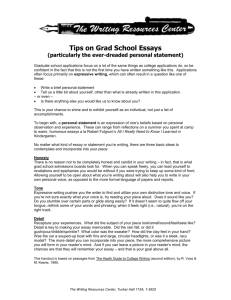

College entrance essays range from the canned to the creative By Olivia Barker, USA TODAY There are as many correct answers to college application essay questions as there are candidates. Still, thousands of anxious high school seniors are spending as much as $300 to craft the “right” response. Essay editing is becoming a requisite to the college admissions game as standardized-test preparation. But as more and more people—parents, teachers, college councilors, entrepreneurial Ivy League graduates—apply red pen to word-processed paper, bleary-eyed admissions officers complain that essays are becoming increasingly homogenized, or so polished that they provoke raised eyebrows. Colleges are growing tired of formulaic compositions on 11th-hour community-service stints and last-minute trips to exotic locales. The best essays, they say, aren’t written over the course of a semester, with the aid of English teachers, but over a few days, in front of desks at home. Successful essays aren’t scripted like history papers but penned like diary entries: thoughtful, whimsical, reflecting what stirs students. To sift the canned from creative, some schools steadfastly eschew the Common Application, which includes the predictable personal statement, and offer their own unusual, if not quirky, questions. Others are more practical, downplaying the importance of the essay altogether and more heavily weighing transcripts, scores and recommendations. “This is not something that should be strategized,” said Robert Kinnally, dean of admissions and financial aid at Stanford. “If you haven’t taken on world peace before, don’t tackle it in your college essay.” This time of year, Kinnally said, his office gets any number of worried calls from seniors stressed out about sending the wrong message. Too often, Kinnally and other admissions deans say, thesaurus-armed students write as though they’re checking off a list: be funny, teach a lesson, write a poem, talk about politics. “We can tell when they’re trying to impress us and when they’re passionate about something,” Kinnally said. “They shouldn’t be the person they think we want them to be.” Essays generally require a signature confirming the student’s sole authorship. But sometimes, too-perfect pieces don’t jibe with teacher comments that criticize a student’s writing. More than once, Kinnally has caught students pulling read-made essays off the internet. Kinnally said some of his favorite essays aren’t about building latrines in a Mexican village, but about punching the cash register at a part-time job at a department store. Most students assume such experiences are too boring, she said, “but they’re learning about attitudes, responsibility, people.” Still, students and parents scanning the best-essay books and web sites find a lot of pieces about extraordinary situations. And alumni magazines have showcased stories about a sister who died of cancer and a boy who was born with only a thumb on his left hand. “It’s hypocritical of schools to promote essays in alumni magazines of disease, handicaps and other impossible, rarefied experiences and wonder why parents are anxious,” said Sanford Kriesberg, a Cambridge, Mass., essay consultant for college and business school admissions. “Eight-five% of kids read the examples and say, ‘Nothing like this has ever happened to me, so what am I going to write about?’ “ said Vedant Mimani, co-founder of New Yorkbased myEssay.com, one of a handful of essay editing companies flourishing on the internet. “But kids don’t need to go out and create tragedy in their lives.” Minami, who hails from a small New Jersey town, applied to Yale eight year ago. “Frankly, I had done nothing,” he said, “I went to school, came home and played sports.” But his essay, about playing games of street football every day and letting his fantasies wander onto the NFL field, helped get him in. “With college essays, it has to be something that sort of flows out, like a College entrance essays range from the canned to the creative freestyle rap over some beat,” said Dan Weisman, 17, from West Newton, Mass. Weisman, who’s applying to eight selective schools, said he has changed his essay, about leaving his native Los Angeles at age 15, very little since he sat down a month ago to write it. His classmates are having a tougher time. Still, he said, “if you can’t find something interesting in your life, you’re obviously not looking hard enough.” Harvard avoids the essay conundrum by minimizing its significance. “We read them, we take them seriously, but they’re not a uniquely valuable credential,” admissions director Marlyn McGrath Lewis said. “People have always been able to get help on essays. That’s the reason why we’ve never valued them so highly.” A beautifully written essay is a “nice thing,” Lewis said. Conversely, a perversely themed essay can be truly damaging. “It raises questions about judgment, taste or character,” she said. “We’re looking for a person her, not an artifact.” At the University of Chicago, essays often carry a lot of weight. But since 1982, they have been unlike those at any other school. Intellectually charged challenges are the norm: Applicants might have to invent a metaphor based on a kitchen object, for example, as in “the expanding universe is like a loaf of bread.” Boasting a set of largely new questions every year, Chicago fancies itself as administering the “uncommon application,” attracting subtle, imaginative, energetic thinkers. The goal is to elicit something fresh from candidates, said admissions dean Ted O’Neill, not something they have been writing over the summer, showing to friends and taking a class. He concedes that the application scares off the sort of kid who would prefer to write just one essay for submission to a dozen schools and get the process over with. “With these questions, we tend to get a more natural product, O’Neill said. “The essays come across as mostly not perfect, a little naïve. They mostly sound like kids.”