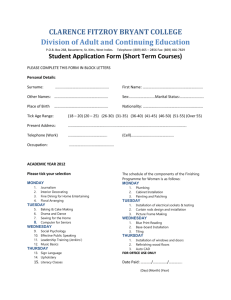

CV 2001-2013 Simon Wachsmuth geboren 1964 in Hamburg, lebt in

advertisement

CV 2001-2013 Simon Wachsmuth geboren 1964 in Hamburg, lebt in Berlin 2013 Archäologie?! Spurensuche in der Gegenwart, Salzburg Museum/Kunsthalle Signatures, Galerie Cora Hölzl, EY-5, Düsseldorf Andere Ordnungen, Haus für die Kunst,Stiftung Wortelkamp, Haselbach Cumuli – Vom Sammeln der Dinge, L40, Berlin On ne connaît les chiffres que d’un côté du plan, art3, Valence Einszehn, Zweizehn, Dreizehn, Kunstverein Friedrichshafen und Zeppelin Museum, Friedrichshafen 2012 Lieber Aby Warburg, Was Tun mit Bildern?, Museum für Gegenwartskunst Siegen Garden of Learning, Busan-Biennale, Süd-Korea Economy: Picasso, Museum Picasso, Barcelona 2010 Atlas, or How to Carry the Worls on One´s Back, Museum Reina Sophia, Madrid , ZKM, Karlsruhe, Sammlung Falckenberg, Hamburg To the Arts, Citizens!, Museo Serralves, Porto Seven little Mistakes, Museo Marino Marini, Florenz Squatting, Temporäre Kunsthalle, Berlin Tanzimat, Augarten Contemporary, Wien 2009 What Keeps Mankind Alive, 11. Istanbul-Bienniale, Istanbul Die Ruhe ist ein spezieller Fall der Bewegung, Kunstmuseum Vaduz/Liechtenstein Reduction & Suspense, Magazin 4, Bregenz 2008 Mnemosyne, Steinle Contemporary, München Acht Minuten, Galerie Hohenlohe, Wien Demonstration IV, Galerie Cora Hölzl, Düsseldorf 2007 a way of considering two things together, Physicsroom, Christchurch, Neuseeland Documenta 12, Fridericianum, Kassel 2006 Soleil Noir, Salzburger Kunstverein, Salzburg the things that I once saw I now can see no more, Kunstraum Dornbirn, Dornbirn 2005 Demonstration, Galerie Stadtpark, Krems Kritische Gesellschaften (Critical Societies), Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe The Government, Be what you want but stay where you are, Witte de With, Rotterdam 2004 The Government: How do we want to be governed, Miami Art Central, Miami Die Regierung: Handlungen, die Handlungen setzen, Kunstraum der Universität Lüneburg Of Copying, Galerie Hohenlohe, Wien 2003 earlgrey, Galerie Cora Hölzl, Düsseldorf Interieur/Exterieur, Remise, Bludenz 2002 Organisational Forms, Galeria SKUC, Ljubljana; Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst, Leipzig 2001 Galerie Hohenlohe & Kalb, Wien The Subject and Power, Haus der Künstler, Moskau As Matter Stands Simon Wachsmuth 3 Channel-Installation, 2012 “Garden of Learning” Busan-Biennale, 2012 Busan, South-Korea Korean Origins Of interest to Simon Wachsmuth are historical periods that vanish in the past. The neolithic age is such a period. We don’t know much about it, and never will, except that it had been a formative age even for our modern ways of inhabiting the world. These were the times when people invented agriculture and social hierarchies. For Garden of Learning, Wachsmuth undertook a journey to Korea’s famous dolmen sites in Gochang, Hwasun, and Ganghwa. The massive stones are markers of burial sites, their formal arrangement clearly reflecting what once was considered appropriate or even necessary, but also what could be done in terms of manpower and technique. In his media installation, Wachsmuth gives an almost documentary account of those sites, projected as blackandwhite video. Two more video sequences are edited in synch with the black-and-white material: views of display cases in a Folk Museum where we can observe the authentic life-style of the neolithic Korean, and a sequence with a group of elderly people who collectively tend the dolmen site, but also engage in singing and dancing. Two small-size screens serve as counter-point to the three big screens. They show the artist’s hands arranging and re-arranging a dolmen model in a playful manner. Roger M. Buergel As Matter Stands In her book „Six Years, the dematerialisation of the art object from 1966 to 1972“, Lucy Lippard notes: „Deliberately low-keyed art often resembles ruins, like neolithic rather than clasical monuments, amalgams of past and future, remains of something „more“, vestiges of some unknown venture. The ghost of content continues to hover over the most obdurately abstract art. The more open, or ambigous, the experience offered, the more the viewer is forced to depend upon his (sic) own perceptions.“ Images and symbols from the past play a powerful role in the present. In many cases we can see how archaeological finds become essential in a modern discourse of identity and nation and how archaeological interpretation can often reflect the policy of either an emerging nation-state or a state in a post-colonial condition. History ceases to be a practice linked to the past and instead reveals the cracks through which it becomes an activity intimately connected to the present. For some time now, Wachsmuths work has been dealing with systems of historical information, which can be traced in historic monuments. For the Documenta12 (2007), the artist has conceived an installation which investigates the relations between Persia/Iran and the western world, along the storylines of the antique ApadanaRelief from Persepolis. At the 9th Biennale of Istanbul (2009), Wachsmuths installation Parabasis has been focusing on the political implications of current archaeological and historical research, encircling the Neolithic, Greek, Byzantine and Ottoman history of Turkey. Within the framework of Korean history, it is the path that leads from the origins of the civilization on the Korean peninsula up to todays understanding of history, that can be found in the centre of Wachsmuths investigation. Especially the Neolithic period marks the beginning of a society with forms of communal life and defined social communities and leadership, a historic moment of transformation still perceptible today. The role of archaeology in Korean society is marked by a specific approach, always being close to the discourse in politics, academia, popular media and the public consience. Archaeological theories, like the categorization of Korean prehistory periods have been important as a way to counter the erroneous claims of Japanese colonial archaeologists who insisted that, unlike Japan, Korea had no "Bronze Age", thus building arguments in a territorial discussion. An interesting topic of archaeological excavations and a visual reminder of early cultures are the neolithic dolmen, monuments constructed of large rocks. These megalithic stones, found both in Asia and Europe, mark prehistoric burial sites. Korea has the largest concentration (40%) of dolmens worldwide. The Korean dolmen are of great value for the information they provide about prehistoric social and political systems, beliefs and rituals, indicating early human presence in the region. Simon Wachsmuths 3-channel video-projection follows the presence of theses stones. In the films, the resource of narration becomes something that updates both history and its visual forms. Filmed within different contexts in Korea, the various formats of appearance of the dolmen are shown - sublime and enigmatic, poetic and hidden as well as popular and commercialized, always hinting at the underlying narrative. Parabasis Simon Wachsmuth Installation, 2009 11. Istanbul Biennale Antrepo & former Greek School Istanbul 2009 Atlas, or how to Carry the World on One´s Back Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid, Spain ZKM, Karlsruhe, Germany Falckenberg-Collection, Hamburg, Germany coming: Archaeology!?, Tracing Roots in Contemporary Art Salzburg-Museum, Salzburg, Austria (October 2013) Parabasis Simon Wachsmuth researches blind spots and unexpected epilogues in the grand narratives of history and art history. He is interested in situations of ignorance and a funamental lack of information, when knowledge about significant phenomenon is missing. His works often use an archival and pseudoscientific approach, and his restricted vocabulary of forms facilitates an openness that prompts us to develop his/her own thoughts and associations. The title of the site-specific project Parabasis (2009) refers to a point in ancient Greek drama when all of the actors leave the stage and the chorus addresses the audience directly, mostly expressing the author´s view on political topics of the day. The artist has attempted to translate the parabasis form, which primarily operates with presence and speech, into the world of images, objects and their representations. Parabasis starts at the oldest man-made place of worship, Göbekli Tepe, built in 10.000 BC, and finishes in 2005 at a site that turned out to be the oldest evidence of settlement in Istanbul, discovered during the construction of the Marmaray, an undersea rail tunnel between Europe and Asia. These prehistoric witnesses constitute an antipode to several important works of Western art, such as Piero della Francescas fresco cycle in Arezzo (1447-1466), which tells the Legend of the true Cross by depicting the triumph of the Emperor Constantine, the founder of Constantinople, or the fragmented Gigantomachia – the Great Altar of Pergamon from the 2nd century BC in the ancient city of Pergamon (modern day Bergama in Turkey) in northwestern Anatolia. These works of art are taken as the starting point to launch a number of contentious issues relating to European and Turkish self-awareness and understanding. Catalogue/Istanbul-Biennale 2009 Parabasis Simon Wachsmuth Installation, 2009 Istanbul-Biennale 2009 - installation view at Antrepo Building Parabasis Simon Wachsmuth Installation, 2009 Atlas, or How to Carry the World on One´s Back, Falckenberg Collection, Hamburg 2010 Parabasis Simon Wachsmuth Installation, 2009 Atlas, or How to Carry the World on One´s Back, Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid, 2009/2010, curated by Georges Didi-Huberman Where we were then, where we are now Simon Wachsmuth Installation, 2007 Documenta12 Kassel, Germany To the Arts, Citizens! Museu Serralves, Porto, Portugal coming: Österreichische Galerie im Belvedere / 21ger Haus, Vienna, Austria (Nov/Dez 2013) Where We Were Then, Where We Are Now The way we approach historical eras is not just characterised by an awareness of loss. Their naming and classification is based on the attempt to at least partially bring back what is irretrievably lost. However this posteriority determines not only our view of the past but also how we look at images of this past: both images that are staged as authentic relics today and those that later generations first develop in engaging with these relics. At the centre of Simon Wachsmuth´s installation is Pesrsepolis, the former royal city of the Achaemenid Empire destroyed by troops of Alexander the Great in 330 BC and now located in Iran. Wachsmuth´s approach to this site, until today often differently symbolically loaded, is not reconstructive or archaeological in the sense of securing findings but a contribution to historical discursivation. The individual parts of the installation correspond in their reduced formal language and black and white aesthetics while their thematic context seems unwieldy at first. The two films show the ruins of Persepolis and Iranian men at the Zourkhaneh practising traditional physical exercises. In the contrast between the paraphrase of the Alexander Mosaic from Pompeii in magnets and the boards showing images and text in the style of Warburg´s Mnemosyne Atlas, the the relationship between the present and the past, as well as between the different cultures, is shown as one open to permanent renegotiation. Behind the conflicting nature of the individual partes, which appear to form a whole through diverging in terms of content, is an insistence on the multivoiced nature of historical narrative, itself constituted far more by fracture than by continuity. Dr. Karin Gludovatz / Documenta 12 catalogue, 2007 Where we were then, where we are now Simon Wachsmuth Installation, 2007 Documenta 12, Kassel, 2007 - Installation view at Friedericianum Where we were then, where we are now Simon Wachsmuth Installation, 2007 Documenta 12, Kassel, 2007 - detail of the magnetic mosaic “Battle of Alexander” Where we were then, where we are now Simon Wachsmuth Installation, 2007 Documenta 12, Kassel, 2007 - Installation view at Friedericianum Where we were then, where we are now Simon Wachsmuth Installation, 2007 Documenta 12, Kassel, 2007 - Filmstill and archival image (Persepolis) Where we were then, where we are now Simon Wachsmuth Installation, 2007 Installation view, Seven Little Mistakes, Museo Marino Marini, Florence 2010 Where we were then, where we are now Simon Wachsmuth Installation, 2007 Installation view, Seven Little Mistakes, Museo Marino Marini, Florence 2010 Where we were then, where we are now Simon Wachsmuth Installation, 2007 Installation view: To the Arts, Citizens! - Museo Serralves, Porto 2010/11 Parathesis Simon Wachsmuth Installation, 2011 Steinle Contemporary, Munich, Germany 2011 Parathesis Simon Wachsmuth Installation, 2011 Photographies and materials from the former image-archive of the Free University Berlin Installation at Gallery Steinle Contemporary, Munich 2011 Parathesis Simon Wachsmuth Installation, 2011 Materials from the former image-archive of the Free University Berlin Index Simon Wachsmuth Installation, 2011 Parathesis, Gallery Steinle Contemporary, Munich 2011 Slide projection with slides from the former image-archive of the Free University Berlin, dimensions variable Untitled (Sanliurfa) Simon Wachsmuth 2009, fineartprints Parathesis, Gallery Steinle Contemporary, Munich, 2011 Aporia / Europa Simon Wachsmuth Installation / painting-cycle, 2008-2010 Aporia/Europa Gallery at the Taxis-Palais, Innsbruck, Austria 2010 Lieber Aby Warburg, Was tun mit Bildern? Museum of Contemporary Art, Siegen, Germany 2012 Aporia / Europa Simon Wachsmuth Installation / painting-cycle, 2008-2010 Gallerie im Taxispalais, Innsbruck 2010