Digital Audio Tape

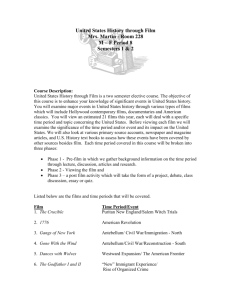

advertisement