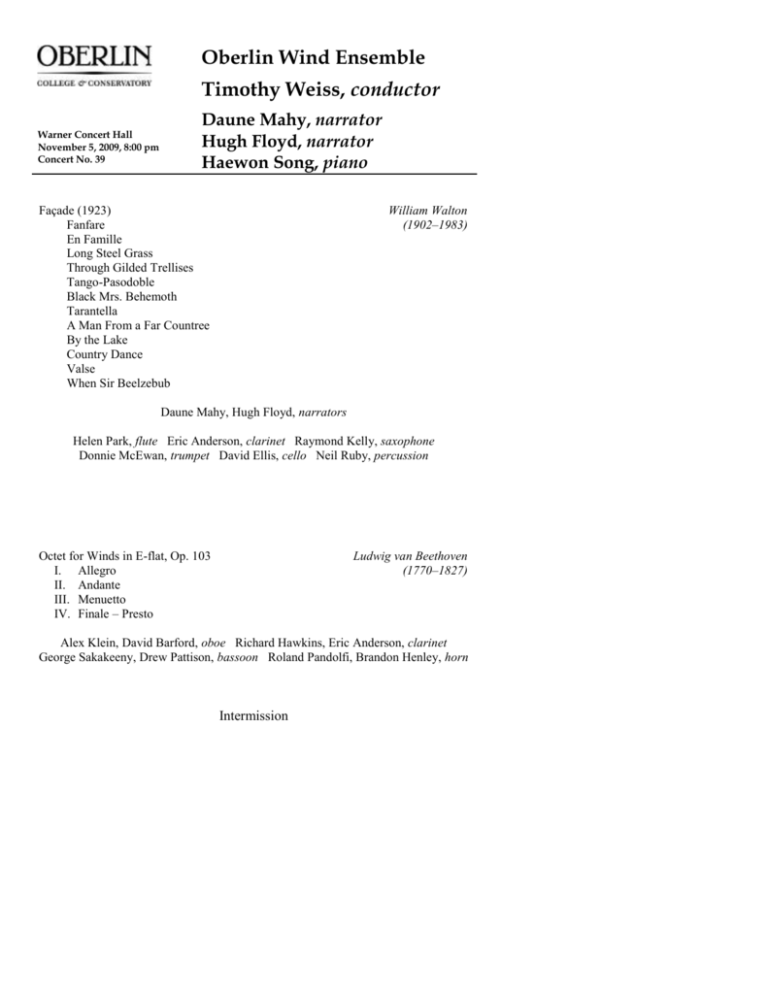

Warner Concert Hall November 5, 2009, 8:00 pm Concert No. 39

advertisement

Oberlin Wind Ensemble Timothy Weiss, conductor Warner Concert Hall November 5, 2009, 8:00 pm Concert No. 39 Daune Mahy, narrator Hugh Floyd, narrator Haewon Song, piano Façade (1923) Fanfare En Famille Long Steel Grass Through Gilded Trellises Tango-Pasodoble Black Mrs. Behemoth Tarantella A Man From a Far Countree By the Lake Country Dance Valse When Sir Beelzebub William Walton (1902–1983) Daune Mahy, Hugh Floyd, narrators Helen Park, flute Eric Anderson, clarinet Raymond Kelly, saxophone Donnie McEwan, trumpet David Ellis, cello Neil Ruby, percussion Octet for Winds in E-flat, Op. 103 I. Allegro II. Andante III. Menuetto IV. Finale – Presto Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) Alex Klein, David Barford, oboe Richard Hawkins, Eric Anderson, clarinet George Sakakeeny, Drew Pattison, bassoon Roland Pandolfi, Brandon Henley, horn Intermission Symphonies of Wind Instruments (1947 revision) Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) Jonathan Figueroa, Gina Gulyas, Laura Smith, flute Pablo Moreno, Jessica Woolf, oboe Eliana Schenk, English horn Dustin Chung, Jane Sandberg, Robert Palacios, clarinet Elizabeth Bennett, Julia Bair, Sean Gordon, bassoon Valerie Sly, Jimmy Haber, Brandon Henley, Ellen Hurley, horn Patrick Rogan, Raymond Bazz, Melanie Mazanec, trumpet Jacqueline O’Kelly, Katherine Robertsad, William Holt, trombone John Geisler, tuba Concerto for Piano and Wind Instruments (1950 revision) I. Largo – Allegro – Più mossos - Maestoso II. Largo - Più mossos – Tempo Primo III. Allegro – Agitato – Lento - Stringendo Haewon Song, piano Annie Gordon, Laura Smith, flute Julianne Bruce, piccolo Eliana Schenk, Jessica Woolf, oboe Pablo Moreno, English horn Jane Sandberg, Dustin Chung, clarinet Julia Bair, Elizabeth Bennett, bassoon Valerie Sly, Brandon Henley, Matthew McLaughlin, Ellen Hurley, horn Donnie McEwan, Patrick Rogan, Oscar Thorp, Melanie Mazanec, trumpet Berk Schneider, Jacqueline O’Kelly, William Holt, trombone John Geisler, tuba Jake Harkins, timpani Greg Whittemore, Adam Bernstein, Will Robbins, bass Donnie McEwan, ensemble manager Michael Roest, ensemble manager & librarian Please silence all cell phones and refrain from the use of video cameras unless prior arrangements have been made with the conductor. The use of flash cameras is prohibited. Thank you. Program Notes Façade (1923) by William Walton (Oldham, Lancashire, England, 1902 - Ischia, Italy, 1983) Few people would have thought it possible that an English composer, from Oxford no less, could produce a work as wickedly funny and irreverent as Façade by 21-year-old Willie Walton. But there it is, a monument to the London edition of the années folles (the crazy years), a most unconventional work that, after 85 years, has not reached the mainstream but is just as unconventional today as it was when it was first performed. Façade is the result of an unlikely partnership between the young Walton and Edith Sitwell, a poet of aristocratic birth and eccentric habits who, 15 years the composer’s senior, ‟adopted” Walton and invited him to live with her and her two brothers Osbert and Sacheverell (also writers) in a rather uncommon household in London. ‟Sometimes I wrote the poems and he put the music to them and sometimes it was the other way around,” Dame Edith recalled many years later. The poems, recited in a strongly rhythmical way, border on the absurd, and the music mixes elements of jazz and cabaret with clear Stravinskian influences. At the same time, one cannot miss the authors’ intent to parody Schoenberg’s Pierrot lunaire both in the external structure (three times seven poems!) and the combination of spoken voice with instrumental ensemble. (At the first performance, the speaker was Edith Sitwell herself.) Façade has become extremely popular as an instrumental suite without the poems, but in such a performance one misses immortal lines such as ‟Daisy and Lily, lazy and silly, walk by the shore of the wan grassy sea.” In later years, Walton went on to compose such lofty and serious masterworks as the oratorio Belshazzar’s Feast, two symphonies, three concertos and much more. Yet in a way he never recaptured the ingenuity and the irresistible sweep of his first major composition. Octet for Winds, op. 103 (1792) by Ludwig van Beethoven (Bonn, 1770 – Vienna, 1827) On November 23, 1793, Franz Joseph Haydn wrote the following letter to Maximilian Franz, the Elector of Cologne who resided in Bonn: Serene Electoral Highness! I humbly take the liberty of sending Your Serene Electoral Highness some musical works: a quintet, an eight-part Parthie, an oboe concerto, variations for the fortepiano, and a fugue, compositions of my dear pupil Beethoven, with whose care I have been graciously entrusted. I flatter myself that these pieces, which I may recommend as evidence of his assiduity over and above his actual studies, may be graciously accepted by Your Serene Electoral Highness. Connoisseurs and non-connoisseurs must candidly admit, from these present pieces, that Beethoven will in time fill the position of one of Europe’s greatest composers, and I shall be proud to be able to speak of myself as his teacher; I only wish that he might remain with me a little while longer. [Haydn then goes on to ask the Elector, who was Beethoven’s patron, to increase the young musician’s stipend which was “not enough to live from”; as he says, he had himself given Beethoven a loan.] This remarkable prophecy on the part of Haydn (who, by the way, wouldn’t remain Beethoven’s teacher much longer) can only be compared to Schumann’s famous words about Brahms some sixty years later: and in both cases, the young geniuses had as yet written none of the music on which their later reputations rested. Some of the Beethoven works Haydn mentions here are lost: to the eternal regret of oboists, his concerto in F, known to have existed, has vanished without a trace (only the slow movement could be recently reconstructed from sketches); the quintet for winds survives as an unperformable fragment, and the piano works can hardly be described as major compositions. The eight-part “Parthie” (an 18th-century term for a multi-movement, serenade-like genre) is a different story. Beethoven himself considered it important enough to arrange it for string quintet, and publish it as his Op. 4 in 1796. (Apparently, the original wind octet version did not find favor with the Elector; it wasn’t published until 1830, three years after Beethoven’s death, under the title “Grand Octuor original.” The high opus number is explained by this late date of publication). The wind octet definitely shows some early marks of genius. Each of its four movements is filled with brilliant new ideas. In the first movement, the amusing alternation of flatted and natural upper-neighbor notes anticipates the minuet of the First Symphony; in the trio of the minuet (which is already a scherzo in all but name), even the bass theme of the Eroica shows up for a split second. The exquisitely scored cantabile melodies of the second movement and the sudden interruptions in the finale are certainly part of what we recognize as “Beethovenian” today. It is likely that Beethoven originally planned this “Parthie” as a fivemovement work. There is a “Rondino” in Andante tempo that was published separately in 1830, the same year as the “Octuor”; on some recordings of the octet, this “Rondino” is inserted before the finale. Symphonies of Wind Instruments (1920, rev. 1947) by Igor Stravinsky (Oranienbaum, nr. St. Petersburg, 1882 – New York, 1971) The unusual grammar of the title Symphonies of Wind Instruments immediately reveals something important about this most unusual composition. The word “symphony” has its roots in the Greek syn (“with”) and phoné (“voice”). The plural form “symphonies” conveys that the work is not a “symphony for wind instruments,” but the “sounding together” of 22 (or, in the original scoring, 23) winds. It is one of Stravinsky’s boldest works. In its quiet and subdued way, it is probably more “modern” than his groundbreaking Rite of Spring, which preceded it by seven years. In Symphonies of Wind Instruments, Stravinsky uses a compositional technique that is perhaps best understood as an analogy of cubist painting. (In the year he wrote this work, Stravinsky also collaborated with Pablo Picasso on the ballet Pulcinella.) The sharply delineated geometric forms of the cubists correspond to abrupt shifts from one musical motif (or theme) to another. This is the first work where Stravinsky consistently did away with transitions and motivic development of every kind. Instead of going over into one another gradually, the themes of the piece form a complex mosaic-like network whose elements combine, conflict, and interlock, but do not affect one another. There are frequent tempo changes in the work, with only three different tempo levels alternating. These tempos – 72, 108, and 144 to the quarter-note – form a simple mathematical ratio, so that the basic metric pulse of the piece never changes. (The piece has only metronomic markings, without traditional tempo designations such as Adagio or Allegro.) In his autobiography, Stravinsky had this to say about Symphonies of Wind Instruments: I did not, and indeed I could not, count on any immediate success for his work. It is devoid of all the elements which infallibly appeal to the ordinary listener and to which he is accustomed. It would be futile to look in it for any passionate impulse or dynamic brilliance. It is an austere ritual which is unfolded in terms of short litanies between different groups of homogeneous instruments. The meaning of this “austere ritual” is revealed in the chorale that closes the work. This chorale was published separately in the periodical Revue Musicale as a homage to Debussy who had passed away in 1918. In retrospect, the entire piece can be seen as a long introduction to the chorale. Concerto for Piano and Winds (1924) by Stravinsky Some composers of the 20th century like Bartók, Prokofiev or Rachmaninoff, were also acclaimed concert pianists. Others, for instance, Schoenberg, Berg or Webern, did not play the piano (or any other instrument) in public. Stravinsky, whose stylistic aboutfaces astounded the world several times during his extraordinary 60-year career, was an exceptional case even here: he could appear as a concert pianist if he wanted to, yet this aspect of his activities was intermittent at best. Concentrating above all on his own works, he performed only when particularly motivated. There is no doubt that the motivation was, at least in part, financial -- he could significantly increase his income if he added a soloist’s honorarium to the composer’s fee. Fifteen years before playing the premiere of his Concerto for Piano and Winds in Paris (under Serge Koussevitzky’s baton), Stravinsky had already appeared as a pianist, performing his early Four Etudes in St. Petersburg. Yet he had not kept up his piano playing over the years. So, in order to master the technical demands of his concerto, he had to get back in shape by practicing the etudes of Carl Czerny several hours a day. The premiere was so successful that Stravinsky played the concerto about 40 times between 1924 and 1928, at which point the need for a second concerto arose, leading to the composition of the Capriccio. The Piano Concerto opens with a solemn introduction whose dotted rhythms allude to French Baroque overtures. Similarly, the Allegro that follows is reminiscent of a Baroque toccata, now percussive and repetitive, now polyphonic, now melodic. It is rare for Stravinsky to repeat a long musical section as literally as he does here: the undisguised symmetry of the movement is one of the most obvious neo-Classical features of the movement. Even the slow introduction returns at the end. The second-movement Largo (Stravinsky called it Larghissimo at first) opens with a simple melody played by the solo piano with chordal accompaniment. The beautiful but somewhat cold theme becomes more animated in the ensuing cadenza, followed by a faster polymetric section. The cadenza and the opening material return in reverse order, giving the music, once again, a symmetrical shape. The finale takes up several motifs from the first movement in varied form. As before, much of the piano part is in continuous sixteenth motion, though the style this time is less Baroque than in the first movement. It was in the finale of his Octet for Winds, written shortly before the concerto, that Stravinsky had first hit upon this particular way of combining echoes of various popular styles with a contemporary idiom, resulting in a movement with equal amounts of melodic charm and harmonic ‟bite.” Although Stravinsky moved very far from his earlier ‟Russian-period” works in the Piano Concerto, we may recognize him, among other things, by his fondness for asymmetrical rhythms that is evident in all three movements of the work. ~ Notes by Peter Laki