Armenian Genocide Education Initiative Center for Peace, Justice

advertisement

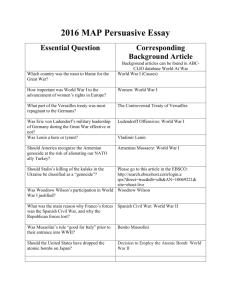

Armenian Genocide Education Initiative Center for Peace, Justice and Reconciliation Bergen Community College 1 What Is the Armenian Genocide? The Armenian Genocide was the deliberate and systematic destruction of the Armenian population of the Ottoman Turkish Empire that was carried out by the Turkish government behind the screen of World War I between 1915-1918. It was implemented through wholesale massacres, and deportations, with the deportations consisting of forced marches under conditions designed to lead to either death, or in the case of many women and children rape and abduction. Thousands of schools, churches, and cultural monuments were destroyed underscoring the cultural dimension of the genocide. The total number of resulting Armenian deaths is generally held to have been between one and one and a half million, about two-thirds of the Armenian population that was then living on its historical homeland of 2,500 years. (From Balakian, Oxford Encyclopedia of Human Rights entry, “Armenians in the Ottoman Empire.” Oxford University Press, 2009) 2 The State of New Jersey Requires This Study Social Studies 6.2 World History/Global Studies All students will acquire the knowledge and skills to think ana systematically about how past interactions of people, cultures, and the environment affect issues a cultures. Such knowledge and skills enable students to make informed decisions as socially and eth world citizens in the 21st century. A Half-Century of Crisis and Achievement (1900-1945) By the end of grade 12 atement Strand CPI# Cumulative Progress Indic A. Civics, 6.2.12.A.4.a Explain the rise of fascism and spread of communism in Europe and Asia. Government, and Human 6.2.12.A.4.b Compare the rise of nationalism in China, Turkey, and India. Rights 6.2.12.A.4.c Analyze the motivations, causes, and consequences of the genocides of Arme (gypsies), and Jews, as well as the mass exterminations of Ukrainians and Ch 6.2.12.A.4.d Assess government responses to incidents of ethnic cleansing and genocide. B. Geography, People, and the Environment 6.2.12.B.4.a Determine the geographic impact of World War I by comparing and contr political boundaries of the world in 1914 and 1939. 6.2.12.B.4.b Determine how geography impacted military strategies and major turnin World War II. 6.2.12.B.4.c Explain how the disintegration of the Ottoman empire and the mandate s creation of new nations in the Middle East. 6.2.12.B.4.d Explain the intended and unintended consequences of new national boun established by the treaties that ended World War II. C. 6.2.12.C.4.a Analyze government responses to the Great Depression and their consequenc Economics, growth of fascist, socialist, and communist movements and the effects on cap Innovation, theory and practice. and Technology 6.2.12.C.4.b Compare and contrast World Wars I and II in terms of technological innovatio industrial production, scientific research, war tactics) and social impact (i.e., mobilization, loss of life, and destruction of property). 3 6.2.12.C.4.c Assess the short- and long-term demographic, social, ec environmental consequences of the violence and destruc World Wars. 6.2.12.C.4.d Analyze the ways in which new forms of communication, and weaponry affected relationships between governme citizens and bolstered the power of new authoritarian re period. 4 5 Why Teach the Armenian Genocide? The extermination of the Armenian population in Turkey in 1915 has been defined by the overwhelming opinion of genocide scholars as the first instance of modern genocide, which is to distinguish it from genocide arried out in a pre-modern era, a human institution that goes back to the Athenians wiping out the Melians or the Romans expunging Carthage. (Chalk and Jonasson, 1985). However, unlike genocidal campaigns before 1915, the Turkish extermination of the Armenians is marked by certain salient features that define what came to be modern genocide: the full use of government apparatus – bureaucracy, military, and technology and communications – in order to first target and isolate and then eliminate an ethnic or culture group – that is, a defenseless sub-group of the larger population – in a concentrated period of time. It is clear as we look back at the twentieth century that the Armenian Genocide became the template for what became modern genocide. When Adolf Hitler said to his military advisors, eight days before invading Poland inb 1939, “Who, today, after all, speaks of the annihilation of the Armenians?” (Lochner, 1942), he was inspired by the 6 fact that Turkey’s ruling party in 1915, the Committee of Union and Progress, had succeeded in eliminating a hated minority population from Turkey. And he was emboldened by the fact that what, for the West, had been the most dramatic human rights disaster of the first quarter of the twentieth century had all but disappeared down the memory hole only twenty years later. So what can we learn from the Armenian Genocide all these years later? For one, we can learn a good deal about how the systematic mass-killing of a targeted population can happen. In the anatomy of the Armenian Genocide plan we see the template for genocide that followed in the twentieth century, in the Holocaust, Cambodia, Rwanda, the Balkans, Darfur and other places. In a century that saw somewhere between 120 and 150 million lives lost to war, genocide and human rights crimes, the significance of the Armenian Genocide is not small. Secondly, we can see in the Armenian Genocide an extreme case of the consequences or genocide carried out with impunity. It seems clear from his exhortation of 22 August 1939 that Hitler was emboldened by the Armenian Genocide and the ensuing impunity granted perpetrators, making clear that genocide committed with impunity encourages more of the same. The failure to bring perpetrators to justice in the aftermath of the Genocide also has created, ninety-three years later, an 7 international scene of seemingly unprecedented denialism on the part of the Turkish government and moral outrage as well as continual wounding for the Armenian community world-wide, and a continuation of human rights abuses and atrocities inside Turkey from 1915 until today. (From Balakian, Oxford Encyclopedia of Human Rights entry, “Armenians in the Ottoman Empire.” Oxford University Press, 2009) Why Was the Armenian Genocide Perpetrated? When WWI erupted, the Young Turk government, hoping to save the remains of the weakened Ottoman Empire, adopted a policy of Pan Turkism – the establishment of a mega Turkish empire comprising of all Turkic-speaking peoples of the Caucasus and Central Asia extending to China, intending also to Turkify all ethnic minorities of the empire. The Armenian population became the main obstacle standing in the way of the realization of this policy. Although the decision for the deportation of all Armenians from the Western Armenia (Eastern Turkey) was adopted in late 1911, the Young Turks used WWI as a suitable opportunity for its implementation. 8 How was the Armenian Genocide Implemented? (From the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute, http://www.genocide-museum.am/) Genocide is the organized killing of a people for the express purpose of putting an end to their collective existence. Because of its scope, genocide requires central planning and an internal machinery to implement. This makes genocide the quintessential state crime, as only a government has the resources to carry out such a scheme of destruction. On 24th of April in 1915, the first phase of the Armenian massacres began with the arrest and murder of nearly hundreds intellectuals, mainly from Constantinople, the capital of Ottoman Empire (now Istanbul in present day Turkey). Subsequently, Armenians worldwide commemorate the April 24th as a day that memorializes all the victims of the Armenian Genocide. The second phase of the ‘final solution’ appeared with the conscription of some 60.000 Armenian men into the general Turkish army, who were later disarmed and killed by their Turkish fellowmen. The third phase of the genocide comprised of massacres, deportations 9 and death marches made up of women, children and the elderly into the Syrian deserts. During those marches hundreds of thousands were killed by Turkish soldiers, gendarmes and Kurdish mobs. Others died because of famine, epidemic diseases and exposure to the elements. Thousands of women and children were raped. Tens of thousands were forcibly converted to Islam. Finally, the fourth phase of the Armenian genocide appeared with the total and utter denial by the Turkish government of the mass killings and elimination of the Armenian nation on its homeland. Despite the ongoing international recognition of the Armenian genocide, Turkey has consistently fought the acceptance of the Armenian Genocide by any means, including false scholarship, propaganda campaigns, lobbying, etc. Chronology of the Armenian Genocide (adapted from Balakian, Armenian Golgotha: a Memoir of the Armenian Genocide, 1915-1918. Knopf, 2009) 1894-1896 Sultan Abdul Hamid II wages an empire-wide campaign of massacres of the Armenian population, in reprisal for largely peaceful protests for reform; approximately 200,000 Armenians are killed. The Sultan was called the “bloody sultan” in the Western press. 10 1908 July 24 The Young Turks (Committee of Union and Progress, or CUP) force Sultan Abdul Hamid II to reinstate the constitution, which leads to the promise of reforms for Armenians and the other minorities in the empire. 1909 April 13 A counterrevolution by the sultan’s supporters and the military in Constantinople stirs anti-Christian feelings throughout the empire. In this context, massacres of Armenians take place in Adana and spread throughout Cilicia, resulting in the deaths of 15,000 to 25,000 Armenians and the destruction of the Armenian sections of towns and villages. April 23 The counterrevolution is quashed by the CUP’s forces and the sultan is deposed. 1912-1913 In the Balkan wars the Ottoman’s lose mare than 80 percent of their European territory and suffer heavy casualties. A mass influx of muslim refugees into Turkey creates increased political animosity toward Christians, and Turkish nationalism intensifies. 1913 January 26 The triumvirate of Ismail Enver, Mehmud Talaat, and Ahmed Jemal stages a coup, taking over the government in the name of an extreme nationalist ideology. 1914 February 8 The Armenian Reform Agreement, whose passage is overseen by the European powers, allows European inspectors to oversee the condition of Ottoman Armenians, angering Turkey. 11 August 1-4 Austria-Hungary declares war against Serbia. Germany declares war on Russia and France. Turkey signs a secret military alliance with Germany. Ottoman troops are effectively placed under German command. World War I begins. August In the cities of the western coast, vandalism and looting of Armenian and Greek shops takes place. Many Greeks are driven out of western Turkey. November 5 Russia declares war on the Ottoman empire. November 9 In Constantinople the Sheikh-ul-Islam proclaims jihad against Christians to incite religious war against the Allies, but also igniting animosity toward the Armenians at home. 1915 January The Russian army routs the Turkish army in the Battle of Sarikamish. The presence of Armenian volunteers in the Russian army stirs more animosity toward Armenians. Armenians in the Ottoman army are disarmed and put into labor battalions, in which they will be massacred in the coming weeks and months by fellow soldiers. February Interior Minister Talaat tells German ambassador von Wagenheim that he is going to resolve the Armenian Question by eliminating Armenians. March Under the direction of the Interior Ministry, Dr. Behaeddin Shakir organizes chetes (mobile killing units) of the Special Organization, mostly comprising thirty thousand criminals released from prison. This is a major component of the government’s plan to annihilate the Armenians. 12 March-April Ittihad (CUP) leaders convey through the Ittihad party network across the empire that Armenians must be deported. Looting, rape, mass arrests, imprisonment and executions of Armenians take place throughout the empire. April 15 Armenian resistance to massacre begins in Van province; they will hold off the Turkish troops for five weeks. April 24 In Constantinople, as British, Australian, New Zealand and French troops prepare to land at Gallipoli, some 250 Armenian intellectuals and community leaders are arrested and sent under armed guard to a prison two hundred miles east. Similar arrests of Armenian intellectuals will continue in other cities throughout the year. Fighting in Gallipoli fuels Turkish rage toward Armenians inside Turkey. May 6 The New York Times reports: “The Young Turks have adopted the policy of [sultan] Abdul Hamid, namely the annihilation of the Armenians.” May 27 The Ittihad government passes the Temporary Law of Deportation, allowing the forcible deportation of all Armenians. June-August Armenians throughout Turkey are arrested in their homes, put on deportation marches, tortured and massacred or abducted. Children are Islamized. Property is confiscated. Turkish refugees from the former European territories are resettled on Armenian lands. July 16 U.S. Ambassador to Turkey Henry Morgenthau cables the secretary of state about “deportation of and excesses against peaceful Armenians,” reporting that “a campaign of race extermination is in progress under pretext of reprisal against rebellion.” 13 August U.S. Consul Jesse B. Jackson reports to Ambassador Morgenthau that more than a million Armenians are believed to be lost. September The Ittihad governement passes the Temporary Law of Confiscation and Expropriation, allowing it to confiscate all real estate and other property belonging to Armenians. In Musa Dagh, Armenians resist deportation and massacre. They hold off Turkish troops for several weeks until 4,058 persons are rescued by English and French warships. This is one of four failed resistances – the others are at Van, Ourfa, and Shabin Karahisar. 1916 July 15 The Russian army defeats the Turkish army in the Caucasus. Russian troops occupy most of western Armenia. July-August Talaat orders a second wave of massacres of Armenians who are still alive in Der Zor. The total killed there exceeds 400,000. August The Interior Ministry abolishes the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople. 1917 April The United States declares war on Germany and Austria-Hungary. Turkey breaks diplomatic relations with the United States. November The Interior Ministry orders all Armenians working on railroad lines to be deported. In Russia, the Bolshevik Revolution ends the Monarchy, soon beginning a civil war. Russian troops leave the Anatolian front, abandoning the Armenians. 1918 14 January In the United States, President Wilson presents his Fourteen Points, including assurances of security and “opportunity of autonomous development” for nationalities under Turkish rule. March 3 Germany, Russia and Turkey sign the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, in which Russia drops out of the war and, among other things, concedes three Armenian provinces to Turkey. November The Allies capture Damascus, Beirut, and Aleppo. The surviving Armenians are rescued. The ruling triumvirate – Talaat, Enver, and Jemal – flees the country. Armistice. 1919 February 1 Under British pressure, Ottoman courts-martial of perpetrators of the Armenian massacres commence in Constantinople. The Ittihad leaders will be sentenced to death in absentia in June; several convictions will result in imprisonment or execution. Although the trials will fall apart by 1920, they will yield hundreds of pages of confessions by perpetrators, which will be recorded in the Ottoman Parliamentary Gazette. May 15 Greece invades Turkey. The Allies have sanctioned the invasion in order for Greece to take back historically Greek territories along the coast of Asia Minor. June President Wilson sends the King-Crane Commission to Turkey to assess the viability of a U.S. mandate for Armenia. The commission will verify the extermination of the Armenians and place the death toll at more than one million. June 10 A military tribunal convicts Talaat, Enver and Jemal and Dr. Nazim of war crimes and sentences them to death in absentia. 15 1920 April The United States recognizes the Democratic Republic of Armenia. In Ankara, Turkish nationalists form a separate government and elect Mustapha Kemal as their leader. The Allies, negotiating the Treaty of Sevres, ask President Wilson to draw the boundary lines of the Armenian Republic. September Kemalist forces launch a major offensive against the Republic of Armenia. They capture the Armenian lands formerly occupied by Russia. November President Wilson submits the boundary lines for a postwar land settlement for Armenia. Turkey is to renounce claims to the ceded lands. The Wilson award reiterates the award to Armenia made in the Treaty of Sevres. 1921 March 16 Turkey and the Soviet Union sign the Treaty of Moscow, wherein they divide the significant parts of historically Armenian lands in the Caucasus between themselves. March 21 Soghomon Tehlirian, a young man who saw most of his family massacred in 1915, assassinates Talaat Pasha in Berlin. He is later acquitted in the assassination. 1922 September Kemalists drive the Greek army out of Turkey. In the process they burn Smyrna and massacre the Greeks and Armenians there. 1923 July At Kemal’s insistence, the European powers sign the Treaty of Lausanne, annulling the Treaty of Sevres. The new treaty recognizes the Republic of Turkey as successor to the Ottoman state and establishes new borders for Turkey. The 16 award to Armenia is scrapped; the word Armenia does not appear in the Lausanne treaty. October 29 The Kemalists proclaim the modern Turkish Republic. 17 Massacre Sites and Deportation Routes 18 Who Are the Armenians? An Ancient Kingdom at the Crossroads of Civilization Armenia dates back as far as the sixth century B.C. originating in the cradle of civilization, the Euphrates valley, and spreading to Asia Minor, in which it became the successor to Urartu in the eighth century B.C. Once spanning the Caucus region from the Caspian Sea to the Mediterranean, Armenia has stood the test of time as a distinctive culture and a unique people, despite numerous conquests over time – from Alexander the Great and Mark Anthony to the Syrians, Persians, Byzantines, Mongols and many more. The First Christian State Because of its geographical position at the crossroads between east and west, Armenia was introduced to Christianity early by the apostles Bartholemew and Thaddeus. In A.D. 301, it became the first nation to adopt Christianity as the state religion. Centuries of Roman, Persian and Turkish Influence Having been under Roman influence after Alexander the Great, Armenia became a Monarchy when Nero appointed Tiridates, a Parthian prince, king of Armenia in A.D. 66. In the third century the Persian king 19 Ardashir I came to power and overran Armenia, beginning several hundred years of Persian rule of the region. Though in the tenth century Armenia gained brief autonomy under native rulers, it again came under outside rule when the Byzantines and later the Seljuk Turks reconquered Armenia. The last Armenian king died in 1375. Thereafter, the Ottoman Turks ruled much of Armenia, though the territory was constantly in dispute between the Turks and the Persians. Armenia Becomes a Russian Province Russia acquired Armenia from Persia in 1828 and made it into a province. The Congress of Berlin in 1878 assigned the Kars, Ardahan and Batumi districts to Russia. Russia later ceded Kars and Ardahan back to Turkey in 1921. First Genocide of the Twentieth Century After Armenia was conquered by the Ottoman Turks, Christians became a minority, and many were subjected to trials and persecutions. Between 1894 and 1915, the Ottomans made a concentrated effort to destroy them. More thasn 300,000 Armenians were killed between 1894 and 1896 and more than 1.5 million were massacred in 1915, in what is now recognized as the first genocide of the twentieth century. 70 Years Under Soviet Rule 20 In the aftermath of World War I, Armenia was given its independence, which lasted only two years until it was overtaken by the Soviets and became a republic of the USSR. In 1988, the Armenian republic suffered a devastating earthquake, which killed more than 25,000 and left more than 100,000 homeless. An Independent State in Transition With the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Armenia again became an independent state, but almost immediately, it became embroiled in a conflict with neighboring Azerbaijan, in a dispute over the Armenian enclave of Nagorno-Karabagh in that country. A cease-fire has held since 1994, but Armenia is still recovering from the effects of both the earthquake and the Azeri war. An estimated 100,000 landmines and unexploded ordnances daily kill or maim Armenian men, women and children. (From the Children of Armenia Foundation, http://www.coafkids.org/ ) What Was Their Status Under Ottoman Rule? The Ottomans conquered Constantinople in 1453 and controlled Anatolia. Under the Ottoman system, Muslims were separated from dhimmi (non-muslims such as Armenians, Assyrians, Greeks, and Jews), 21 who lived in self-governing communities called millets. Armenians were allowed to run their communities’ internal affairs under government protection and rule. In this system, however, dhimmi had few legal rights, and none in Islamic courts; thus Armenians – with no protection from theft and extortion and the rape and abduction of women – were in perpetual jeopardy. They were not allowed to own weapons or join the military or civil service, which excluded them from the power structure and made them prey, subjected to a corrupt tax-farming system wherein they were forced to pay redundant rounds of taxes to extorting local officials. They were required to wear distinctive dress and defer to Muslims in public. (From Balakian, Oxford Encyclopedia of Human Rights entry, “Armenians in the Ottoman Empire.” Oxford University Press, 2009) 22 Denial of the Armenian Genocide Genocide scholars around the world concur that the mass killing of the Armenians in Turkey in 1915 is genocide. And, the most minimalist of genocide scholars concur that only three events qualify as genocide in the 20th century: the Armenian genocide, the Holocaust, and the Rwandan genocide. Only the Turkish government and a handful of scholars who have been enlisted into supporting Turkey’s nationalist agenda deny the Armenian genocide. Raphael Lemkin, the PolishJewish legal scholar who created the concept of genocide as a crime in international law did so largely on the basis of what happened to the Armenians in Turkey in 1915, and to the Jews in Europe in the 1940s. Lemkin was the first to use the term Armenian genocide and he wrote about the mass killing of the Armenians repeatedly in his work, and as he put it in a letter to Thelma Stevens in the summer of 1950 as he was working hard for the passage of the UN Genocide Resolution in the US, “I know it is very hot in July and August for work and planning, but without becoming sentimental or trying to use colorful speech, let us not forget that the heat of this month is less unbearable than the heat of the ovens of Auschwitz and Dachau and more lenient than the murderous heat in the desert of Aleppo which burned to death the bodies of hundreds of thousands of Christian Armenian victims of genocide in 1915.” 23 Raphael Lemkin on the Armenian Genocide “The precise and legally correct term for the intended group destruction of the Armenians in 1915 by the Turkish government was first named Armenian genocide by Raphael Lemkin, the Polish-Jewish legal scholar who created the term genocide in 1943, and did so in good part based on the intended group destruction of the Armenians in Turkey in 1915. In 1949, when explaining the definition of genocide, Lemkin wrote: ‘Genocide is defined in this convention as the intentional destruction of national, racial, ethnical and religious groups. Examples of genocide are the destruction of the Armenians in the first World War, and the destruction of Jews in the second World War.’ To Lemkin, both cases were unequivocally acts of genocide. Although the Holocaust had a direct and personal bearing on Lemkin, who lost 49 members of his family to the Nazis, Lemkin explicitly argues that there is no hierarchical value placed on genocides. In 1948, he wrote: ‘In 1916 and thereafter, President Wilson took a warm interest in the faith of the Armenians, who fell victims of genocide. More than 1,200,000 men, women and children were massacred at that time. The USA State Department wrote ‘The government cannot be a tacit part of an international wrong.’ The genocide convention condemns mass violence as a system of government. This crime did not start with Hitler and did not end with Hitler.’ 24 1) Armenian genocide as a primary focus for Lemkin ‘Soon contemporary examples of genocide followed, such as the slaughter of Armenians in 1915. It became clear to me that the diversity of nations, religious groups and races is essential to civilization because every one of these groups has a mission to fulfill and a contribution to make in terms of culture… “After the end of the war, some 150 Turkish war criminals were arrested and interned by the British government on the island of Malta. The Armenians sent a delegation to the peace conference at Versailles and demanded justice. Then one day, I read in the newspaper that all Turkish war criminals were to be released. I was shocked. A nation that killed and the guilty persons set free. Why is a man punished when he kills another man? Why is the killing of a million a lesser crime than the killing of an individual? I didn’t know all the answers, but felt that a law against this type of racial or religious murder must be adopted by the world.” 2) Lemkin on Armenians and Jews as victims of genocide in the 20th century “On the 9th of December, 1948, the General Assembly of the United Nations in Paris adopted an international convention or a treaty for the prevention and punishment of the crime of genocide. Genocide is 25 defined in this convention as the intentional destruction of national, racial, ethnical and religious groups. Examples of genocide are the destruction of the Armenians in the first World War and the destruction of the Jews in the second World War.” 3) Lemkin on the Armenian Genocide and destruction of Armenian culture “In terms of the larger issues involved, the losses in culture through the genocide of the Armenians in Turkey were staggering. The Armenians, as the intellectual core of Turkey, were in possession of valuable personal libraries, archives, and historical manuscripts, which were dispersed and lost. Churches, convents, and monuments of artistic and historical value were destroyed…” (Complied by Donna Lee-Frieze, Deakin University, Melbourne Australia) World Opinion on the Armenian Genocide In the face of Turkish denial, scholars, organizations and nations, motivated by an ethical sense and the value of historical honesty, have made statements of acknowledgement and affirmation of the Armenian genocide. The International Association of Genocide Scholars has issued several Open Letters which underscore that the historical record of the Armenian genocide is overwhelming and unambiguous, and noting 26 Raphael Lemkin’s first use of the term genocide to describe the Armenian case, and the applicability of the 1948 United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (IAGS, 2006). More than twenty countries as well as the Vatican and the European Parliament have passed resolutions acknowledging the events of 1915 as genocide. Nobel Laureate Elie Wiesel has called Turkish denial a “double killing” that strives to kill the memory of the event. Deborah Lipstadt has written: “Denial of genocide whether that of the Turks against the Armenians, or the Nazis against the Jews is not an act of historical reinterpretation…The deniers aim at convincing innocent third parties that there is another side of the story…when there is no other side…Denial of genocide strives to reshape history in order to demonize the victims and rehabilitate the perpetrators, and is the final stage of genocide.” (Lipstadt, 2000). While Turkish denial has been discredited by the mainstream scholarly community, students of the Armenian genocide should be alert to the nature of denialist literature and its connection to Turkish nationalism. 27 Why Does Turkey Deny the Armenian Genocide? (From Taner Akcam, “Facing History: Denial and the Turkish National Security Concept,” lecture at Bergen Community College 2011) When Michael Hagopian made his first classic acclaimed documentary on the Armenian genocide in 1975, which was nominated for two Emmys, he called it “Forgotten Genocide.” It would be less accurate to call it that today, though it remained forgotten and taboo in Turkey until quite recently. Those who have made working on this topic a life long commitment have struggled to answer the million dollar question: Why has the genocide been buried under so much amnesia and rendered such a taboo subject in Turkey? Undoubtedly one could cite many reasons, but I am going to discuss just one of them and that is the ‘security concept.’ One of the main reasons why the Armenian genocide has been virtually forgotten and the subject made such a taboo in Turkey is the fact that in Turkey discussing it is considered a threat to national security. Anyone who even dares bring up the subject runs the very real risk of being labeled a traitor to the nation, dragged from courtroom to courtroom in prosecutions, not to mention, even assassinated. The mindset hat an open discussion of history engenders a security problem originates from the breakup of the Ottoman Empire into nation28 states starting in the nineteenth century. From late Ottoman times to the present, there has been a continuous tension between the state’s concern for secure borders and society’s need to come to terms with abuses of human rights. Within this history, security and territorial integrity of a crumbling Empire, and human rights abuses were forged with a common fate, they were the two faces of the same coin. It is precisely this intertwining of the two that is the underlying cause of the amnesia and taboo surrounding the Armenian genocide in Turkey. When the first World War ended with Ottoman defeat, working out the terms of a peace settlement, the political decision makers of the time grappled with two distinct, yet related issues, the answers to which would determine their various relationships and alliances. The first was the territorial integrity of the Ottoman state. The second was the wartime atrocities committed by the ruling Union and Progress party against Ottoman Armenian citizens. The questions about the first issue were: Should the Ottoman state retain its independence? Should new states be permitted to arise on the territory of the Ottoman state? The questions regarding the second issue were: What can be done about the wartime crimes against the Armenians and the perpetrators of these atrocities? How should the perpetrators be punished? The fact is that the attempt at dismemberment and partition of a state as a form of punishment for the atrocities committed during the war years 29 and proposed punishment of its nationalist leaders for seeking the territorial integrity of their state, created the mindset in Turkey today that views any reference to the historic wrongdoings in the past as an issue of national security. A product of this mindset is therefore a belief that democratization, freedom of thought and speech, open and frank debate about history, acknowledgement of one’s past historical misdeeds, is a threat to national security. You cannot solve any problem in the Middle East today without addressing historic wrong doings because history is not something in the past; past is the present in the Middle East. Putting it another way, one of the main problems in the region is the insecurity felt by different groups and states towards each other as a result of events that have occurred in history. When you make the persistent denial of these painfilled acts a part of your security policy this brings with it insecurity towards the other. This is what I call the security dilemma: What one does to enhance one’s own security causes a reaction that, in the end, can make one even less secure. For this reason, any security concept … that ignores and forgets the addressing of historic wrong doings is doomed to fail in the end. 30 Steps to Organized Genocide Denial of Justice Isolation Propaganda Persecution Violence The Eight Stages of Genocide 1. CLASSIFICATION: All cultures have categories to distinguish people into “us and them” by ethnicity, race, religion, or nationality: German and Jew, Hutu and Tutsi. 2. SYMBOLIZATION: We give names or other symbols to the classifications. We name people “Jews” or “Gypsies”, or distinguish them by colors or dress; and apply the symbols to members of groups. Classification and symbolization are universally human and do not necessarily result in genocide unless they lead to the next stage, dehumanization. 3. DEHUMANIZATION: One group denies the humanity of the other group. Members of it are equated with animals, vermin, insects or diseases. Dehumanization overcomes the normal human revulsion against murder. At this stage, hate propaganda in print and on hate radios is used to vilify the victim group. 31 4. ORGANIZATION: Genocide is always organized, usually by the state, often using militias to provide deniability of state responsibility. Special army units or militias are often trained and armed. Plans are made for genocidal killings. 5. POLARIZATION: Extremists drive the groups apart. Hate groups broadcast polarizing propaganda. Laws may forbid intermarriage or social interaction. Extremist terrorism targets moderates, intimidating and silencing the center. 6. PREPARATION: Victims are identified and separated out because of their ethnic or religious identity. Death lists are drawn up. Members of victim groups are forced to wear identifying symbols. Their property is expropriated. They are often segregated into ghettoes, deported into concentration camps, or confined to a famine-struck region and starved. 7. EXTERMINATION begins, and quickly becomes the mass killing legally called “genocide.” It is “extermination” to the killers because they do not believe their victims to be fully human. When it is sponsored by the state, the armed forces often work with militias to do the killing. 8. DENIAL is the eighth stage that always follows a genocide. It is among the surest indicators of further genocidal massacres. The perpetrators of genocide dig up the mass graves, burn the bodies, try to cover up the evidence and intimidate the witnesses. They deny that they committed any crimes, and often blame what happened on the victims. (Gregory Stanton, President, Genocide Watch http://genocidewatch.org) 32 33