File - Anna Hays: Professional Portfolio

advertisement

Running head: BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

Brief constructed responses and an unknowing reactive audience

Anna B. Hays

University of Maryland University College

1

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

2

Part I: Introduction

Background

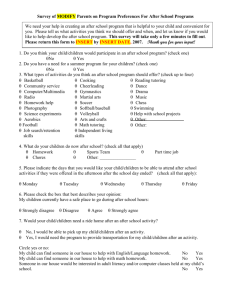

Co-researchers participating in the initial stage of a joint program between the

Masters of Arts in Teaching Program (MAT), University of Maryland University College

(UMUC), Adelphi, Maryland, and the Ernest Everett Just Middle School (EEJMS),

Mitchellville, Maryland, were tasked with the creation and implementation of a pilot

action research project. The project was required to involve assessment and be carried out

during a series of weekly hour-long tutoring sessions, originally numbered at 10. One

white 40-year-old female UMUC MAT candidate holding an MA in English was paired

with Girl A and Girl B, two female African-American seventh-grade EEJMS students

performing below grade level in their shared language arts class. Additional coresearchers included the students’ language arts classroom teacher, Teacher X, their

school counselor, Counselor Y, and a member of each girl’s family, Girl A’s

grandmother, a high school graduate, and Girl B’s mother, a college graduate.

UMUC tutors were volunteers from the EDTP 645, Subject Methods and

Measures, class during spring semester 2011. EEJMS students were nominated by their

core subject teachers for inclusion in the program. In addition to the prerequisite of

teacher nomination, students needed a consent form signed by a parent/guardian

(Appendix A) and a behavior and academic contract signed by both the student and a

parent/guardian (Appendix B) in order to participate.

EEJMS was chosen as the partner school because of its proximity to the tutoring

site. Tutoring sessions were held in the cafeteria of the UMUC Largo campus in Upper

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

3

Marlboro, Maryland, just 1.5 miles from EEJMS. EEJMS is a struggling school. While it

managed to attain adequate yearly progress (AYP) during school year 2008–2009; during

school year 2009–2010, overall scores dropped in all categories except for 7th grade

reading. Even in this category, however, the school failed to make AYP in the following

subcategories: African-American, Free/Reduced Meals, Special Education, and All

Students (http://msp.msde.state.md.us/aypintro.aspx?AypPV=14:0:16:1348:3:000000).

Perhaps as a direct consequence of this failure, enrollment in the school decreased from

963 students in 2009–2010 to 800 in 2010–2011, a 17% drop.

The student body is composed of 96% African-American, 2% Hispanic, 1%

Asian, and <0.5% American Indian or White students; 30% qualify for free or reduced

meals, and 10% are labeled special education. One hundred percent of the staff is

certified, with 35% having 10 or more years of teaching experience (Carter, 2010). Of

particular interest to this study, during a school climate survey conducted during school

year 2008–2009 at EEJMS, the characteristic receiving the lowest percentage of positive

perceptions was parent/community involvement, at 55.9%, though this was much higher than

the Prince George’s County, Maryland, county-wide percentage of 44.1%

(http://survey.pgcps.org/2009_School_Climate/SY09EJUST.pdf).

Girls A and B made up part of the 13.3% of EEJMS African-American females

who scored below proficient levels in reading on the 2010 Maryland State Assessment

(http://msp.msde.state.md.us/statDisplay.aspx?PV=2:7:16:1348:3:N:8:1:1:1:1:1:1:1:3).

They both experienced difficulty in their 7th grade language arts class, performing far

below grade level. Each received a D in the grading quarter immediately preceding the

beginning of the tutoring sessions; in addition, both students scored below C in science

and social studies, their other text heavy core courses. Teacher X nominated both Girl A

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

4

and Girl B for inclusion in the UMUC tutoring program and indicated, via Counselor Y,

who attended all tutoring sessions, that both students needed extra work in reading

comprehension. Both students explicitly asked for help with brief constructed responses,

and neither student arrived at tutoring prepared with “questions, concerns, problems” or

“textbooks, notes, and assignments” (see Appendix B, “I will arrive prepared”

bulletpoint).

Problem

Brief constructed responses (BCRs) are written responses to stimulus material,

usually composed in answer to a prompt. They generally consist of one paragraph

comprising three elements: a topic sentence, supporting details from the stimulus text,

and a conclusion. Two common characteristics of weak BCRs, those scoring below 2 on

the Maryland English Rubric: Brief Constructed Response (Appendix C; see also

http://mdk12.org/instruction/curriculum/hsa/language_arts/eng_rubric_template_bcr_is.ht

ml), are (1) a failure to support with textual detail the answer provided in the student’s

topic sentence to the question either stated or implied by the prompt and (2) a failure to

actually provide such an answer to the prompt. The cause of these failures is unknown,

but one hypothesis is that students either consciously or subconsciously assume the

reader/grader to be an expert member of the Discourse in which that student is a flailing

apprentice. Here Discourse with a capital D represents a “wrapping together of the

individual, the cultural, and the social…as [students] interact with others and work to

become members of different communities of practice” (Magnifico, 2010, p. 173; see

also Snowman, McCown, & Biehler, 2009, pp. 46–51). Providing textual details,

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

5

therefore, would seem redundant as the reader already has an intimate knowledge of

them, and providing an explicit answer to the prompt risks confirming the student’s

perceived inability to participate in the Discourse (performance-avoidance goal; see

Snowman et al., 2009, pp. 410–411). Such disaffiliated students are at risk for low selfefficacy in relation to school and its Discourse, in general, and specifically to BCRs.

“Students who do not believe they have the cognitive skills to cope with the demands of a

particular subject are unlikely to do much serious reading or thinking about the subject”

(Snowman et al., 2009, p. 278). It is not known whether or to what extent establishing an

interactive audience, a personification of Vygotsky’s mediation, outside the perceived

Discourse will allow students to be pulled through their zones of proximal development

toward an increased self-efficacy and a strengthening of the BCRs.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to determine whether providing an unknowing

reader, someone unfamiliar with the stimulus text, as an interactive initial audience for

the student’s BCR resulted in improvement in the quality of the BCR. In this case, this

unknowing audience was a student-selected family member. A family member was

chosen because (1) they would represent the student’s primary Vygotskian expert and (2)

they would be most likely to trigger an emotional arousal, one of the four factors believed

to influence self-efficacy (Snowman et al., 2009, pp. 279–280). BCR quality was

evaluated on two forms of each BCR. The first form was the initial attempted BCR, and

the second form was the revised BCR, with revisions done as a result of audience

reaction.

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

6

Significance

Brief constructed responses support learning in all the core subject areas by

supporting reading comprehension and exercising higher-order thinking. At a macro

level, such higher-order thinking is a necessity for escaping Dewey’s static society, a

society “which makes the maintenance of established custom their measure of value,”

and moving to a progressive society in which each successive generation advances

beyond the one before (Dewey, 2001, p. 41). On a more micro level, BCRs appear on the

Maryland State Assessment (MSA), a test given in accordance with No Child Left

Behind, which occurs in March of each school year for students in grades 3–8. In

addition, Magnifico (2010) makes a call for more studies of the effect of audience on

writing, especially an interactive audience:

There has, thus far, been little new research in the areas of education or

psychology that focuses specifically on the concept of audience. Although

the identity literature, which focuses on how individual learners see and

understand themselves, is burgeoning, there has been little attention paid

to the other side of identity—how it is enacted for the audience.

Sociocultural research into how teachers might transform their classrooms

into communities of practice with authentic audiences is undoubtedly

relevant here, especially in terms of thinking about the implications of a

participatory audience. (p. 180)

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

7

While Magnifico (2010) is writing within the context of high-tech writing

communities (e.g., blogs), this study presents a low-tech, and therefore

universally accessible, answer to her call.

Research Question

Can utilizing a family member as an unknowing reactive audience improve the

quality of the BCR?

Part II: Literature Review

The National Reading Panel, in its 2000 report, recommended seven reading

strategies supported by research. Among these are comprehension monitoring, question

answering, and use of graphic organizers (Alvermann, Phelps, and Ridgeway Gillis,

2010, p. 198). The first two are inherent components of brief constructed responses, and

are often supported by the third. The BCR prompt is either an explicitly or implicitly

stated prereading question used to guide student’s reading and, therefore, comprehension

of the stimulus text. “Prereading questions in effect tell the readers what to look for and,

by implication, what to ignore” (Alvermann et al., 2010, p. 204). Comprehension is

bolstered through a more efficient targeting of significant information.

While BCRs require the use of textually explicit supporting details, such as those

targeted through prereading strategies, they generally require that students move beyond

mere restatements of fact (Bloom’s taxonomy level 1: knowledge; see Wong & Wong,

2010, pp. 236–237) by generating both textually and scriptally implicit answers, answers

derived using higher-order thought processes from levels 2–6 of Bloom’s taxonomy

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

8

(Alvermann et al., 2010, pp. 204–205; Wong & Wong, 2010, pp. 236–237). Application

of structured metacognitive tasks, such as listing and explaining their revisions (see

Kinsler, 1990; Raphael, 1982, 1984, 986 as cited in Alvermann et al., 2010, p. 208), have

been shown to further reinforce development of higher-order thought processes, one end

goal of education. In addition, writing helps students to “’step back from the text after

reading it—they reconceptualize the content in ways that cut across ideas, focusing on

larger issues or topics. In doing this, they integrate information and engage in more

complex thought’ (p. 406)” (Judith Langer, 1986, in Alvermann et al., 2010, pp. 311–

312).

In fact, Dewey’s entire philosophy of education can be said to revolve around

developing a student’s ability to apply higher-order thought processes. This ability is

what saves a society from stagnation. A static society is one whose educational goals are

merely to recreate the world as it is: to have students merely catch up with adults.

Progressive communities rather “endeavor to shape the experiences of the young so that

instead of reproducing current habits, better habits shall be formed, and thus the future

adult society be an improvement on their own” (Dewey, 2001, p. 41). His exploration of

the interconnectedness of society and education paved the way for future sociocultural

philosophies like Vygotsky’s and sociocognitive philosophies like Bandura’s.

Vygotsky’s view of cognitive development sounds like Dewey’s description of

the static society: “education of the immature fills them with the spirit of the social group

to which they belong…a sort of catching up of the child with the aptitudes and resources

of the adult group” (Dewey, 2001, p. 41). While Vygotsky’s theory does not result in a

static society, Vygotsky does view social interaction as the primary cause of cognitive

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

9

development. Cognitive development takes place through mediation, which occurs when

an expert member of the culture, beginning with a child’s parents, interprets the child’s

behavior and “helps transform it into an internal and symbolic representation that means

the same thing to the child as to the others” (Snowman et al., 2009, p. 48). That is, adults,

or community experts, beginning with the parents, aid children in the use of a culture’s

psychological tools (“the cognitive devices and procedures with which we communicate

and explore the world around us,” Snowman et al., 2009, p. 47). The end goal is to move

the child through a period as a novice member of the community during which they can

use the psychological tools with the aid of an expert and on to a time when they are able

to use the tools alone.

But what if a student inhabits a Discourse that is other? Magnifico (2010)

indicates:

As a prescription for the design of literacy learning environments,

however, sociocultural theory presents challenges because of its focus on

how learning and membership occur, often gradually, in the context of a

community as a whole. These challenges are particularly significant for

educators working within the climate of schools because any school has

already-existing institutional norms and Discourses that are inherent parts

of any in-school design. These existing elements of context can present

roadblocks in the building of a successful literacy community, especially

for teachers who are teaching students who do not share the dominant

Discourse of school. (p. 174)

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

10

That is, such students are novices in a different cultural community from that in which

the teachers are experts. Thus, such students are likely to hold a low self-efficacy in

relation to their ability to use the psychological tools of the teacher’s Discourse.

Bandura’s social cognitive theory recognizes how personal characteristics, such as

self-efficacy, interact with behavioral patterns and Vygotsky’s sociocultural elements to

determine a cognitive result (Snowman et al., 2009, pp.276). In fact, self-efficacy may be

the most influential characteristic:

Students who believe they are capable of successfully performing a task

are more likely than students with low levels of self-efficacy to use such

self-regulating skills as concentrating on the task, creating strategies, using

appropriate tactics, managing time effectively, monitoring their own

performance, and making whatever adjustments are necessary to improve

their future learning efforts. (Snowman et al., 2009, p. 279)

On the other hand, students with low self-efficacy are more likely to avoid

situations where they feel incapable of succeeding. They feel a disincentive to

invest time or effort since the likely result is failure. Failure to try allows blame to

be placed on circumstances rather than on inability (performance-avoidance

goals; Snowman et al., 2009, p. 410). Their low self-efficacy, therefore, leads to

poor self-control and self-regulation.

Because such students are unable to control their own actions, a proxy

regulator or audience may be called for. By affecting the four antecedents of selfefficacy (performance accomplishments, verbal persuasion, emotional arousal,

and vicarious experience; Snowman et al., 2009, pp. 279–280), proxy regulators

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

can transform learning and growth motivational goals. Students with low selfefficacy maintain a goal of safety, which prompts them to avoid failure. However,

a proxy regulator, especially one who shares a common Discourse or cultural

background with the student, who experiences vicarious success in the school’s

Discourse can influence a student to move from Maslow’s goal of safety to a goal

of belongingness or love associated with performance approach learning goals

and possibly on to esteem associated with task mastery learning goals (see

Snowman et al., 2009, pp. 410, 429). The emotions engendered by these goals

outweigh those aroused by fear of failure in the Discourse. The scaffolding thus

results in an increase in performance, leading to an increase in encouragement and

praise (verbal persuasion), a decrease in fear and loathing and an accompanying

increase in desire to please and belong (emotional arousal), and an increased

connection with the proxy who is succeeding in the Discourse (vicarious

experience) as well as with the Discourse itself, all of which results in an increase

in self-efficacy that not only incrementally reinforces this cycle but also leads to

an increase in self-control and self-regulation. Thus the proxy has scaffolded the

student to self-regulation or reached Vygotsky’s goal of use of the psychological

tools without the aid of the adult expert.

This proxy regulator is a reactive audience for the student. In Magnifico’s

(2010) conclusion to her review of the literature surrounding cognitive and

sociocultural conceptions of audience, she supports the introduction of an

interactive audience and suggests that “constructing authentic writing situations in

literacy learning environments can help writers to plan their writing using a

11

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

conceptual referent and to be cognizant of the social, communicative context in

which that writing is situated” (p. 176). She goes on to describe a middle school

writing experiment in which students writing for their teacher wrote much weaker

compositions than those same students did in a more authentic writing situation:

writing to pen pals. The authors of the study suggest that the students’ familiarity

with the teacher, their shared classroom experiences, caused them to take too

much for granted in the writing. They were unable to write to an abstract

audience, nor were they yet experts in the shared classroom Discourse. “When

writing for an authentic audience of overseas pen pals, however, students were

forced to reflect on what the audience needed to know, and this additional thought

and planning aided them in producing clearer, better organized compositions”

(Magnifico, 2010, p. 177).

Wong and Wong’s (2010) call for inviting the parents to participate in

their child’s education indicates a good starting point in the search for an

authentic audience. Dr. Marian White Hood (former principal of EEJMS) issued

such an invitation:

We encourage EVERY parent to speak with their child about their reading

skills, their writing ability, and discuss with their child what they are doing

in school. By simply showing your interest in your child’s school

progress, asking them to show you samples of their school work, a piece

of writing, and their organization, YOU make a major difference in their

progress.” (Retrieved from

http://www.pgcps.org/~eejust/Principal_Message%20update.htm)

12

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

Jones (2008/2009) believes that “most parents today more than welcome ideas to

enrich their children’s educational experiences (and test scores), they often don’t

know where to begin” (p. 37). She thus reiterates the need to invite the parents to

be part of their child’s education. She outlines several easy-to-implement methods

designed to help parents increase students’ scores on the high-stakes assessments,

such as Standards of Learning Tests (or MSAs). She suggest that parents should

encourage students to read the questions first (pre-reading strategy) and to answer

using complete sentences, which forces students to practice including supporting

details in their answers. She also suggested that parents provide a second set of

eyes for students’ assignments. “This method also provides a wonderful

opportunity for discussions as parents share their own ideas and make connections

to what is being read or studied by their child” (Jones, 2008/2009, p. 38). In at

least one study involving reading comprehension, the group that not only received

strategy instruction and had books chosen for them that matched their interests

and reading level but also was required to tell a member of their family about the

book and read to them one small section made the most significant gains in

reading level attained and comprehension. The largest improvements within this

group were seen for black, Hispanic, and low-income students (White and Kim,

2008). Therefore an attempt to invite a family member to act as an unknowing

interactive audience for brief constructed responses in support of their student’s

increased reading comprehension seems warranted.

13

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

14

Part III: Methodology

Gain Access to Site via Organic Means

Access to students was gained through a partnership created between UMUC’s

MAT program and EEJMS. EEJMS English students who fulfilled the requirements of

program participation were divided by grade, and each grade was assigned to one of the

two UMUC MAT volunteer tutors seeking teaching certification in secondary English.

The two seventh grade students were tutored at a round table for four in the back of the

cafeteria on the UMUC Largo Campus on Saturdays from 9:00 AM to 10:00 AM

beginning Saturday, February 12, 2011. The table was located away from all windows

and separated from other distractions, including two other EEJMS-UMUC tutoring

groups, by a flipchart acting as a temporary wall.

Dialogue

UMUC volunteer tutors arrived for the first day of tutoring knowing only the

general subject area in which they would be working. They had no idea how many

students they would have, what grade these students would be in, or what topics would

need to be covered. The tutors were met in the cafeteria by Counselor Y, who acted as a

liaison between the tutors and EEJMS teachers, students, and families. She handed out

the tutoring assignments, copies of the signed parent letters, inclusive of contact

information, and copies of the signed behavioral contracts. Once students arrived, tutors

and tutees adjourned to discuss their mutual needs from the tutoring sessions. Only Girl

A showed up for the first session, walking into the cafeteria alone. When Girl B arrived

during week 2, she was accompanied by both parents, though they are divorced. The tutor

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

15

made a point of talking to both parents, providing them with her contact information, and

indicating that she would be contacting them by telephone shortly to discuss further the

tutoring sessions.

Establish a Community of Co-researchers

Though contact had been made with some family members, at this point, coresearchers included only the tutor, the two tutees, Counselor Y, and to some extent

Teacher X. The final two co-researchers, the two family members, would not come

onboard until just before the implementation stage.

Collective Problem Formation

Girls A and B arrived at the tutoring sessions without specific questions or

homework but with important critical knowledge: the awareness of their need to improve

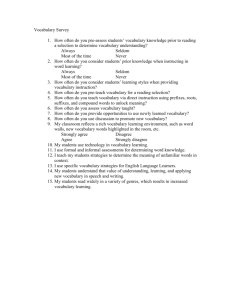

their BCRs. Counselor Y filled a hole in the tutor’s technical knowledge by defining

these as brief constructed responses and in her critical knowledge by outlining their

significance in relation to the MSAs. She provided a link to the School Improvement in

Maryland Website (http://mdk12.org/assessments/k_8/index.html), which included public

BCR sample stimulus texts and prompts, sample student responses, and sample annotated

assessments of these responses in relation to the state BCR rubric, the link for which was

also provided by Counselor Y

(http://mdk12.org/instruction/curriculum/hsa/language_arts/eng_rubric_template_bcr_is.h

tml). Counselor Y also utilized interactive knowledge by approaching the language arts

teacher in advance to find out in what areas Teacher X felt the students needed the most

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

16

help. Teacher X indicated both Girl A and Girl B needed work in reading comprehension.

Through exploration of the School Improvement in Maryland Website, as well as

additional Websites (e.g.,

http://www.montgomeryschoolsmd.org/schools/bealles/bealles/forparents/bcr.html,

http://www.fsk.org/teachers/writing_BCR1.html, and

http://teachers.bcps.org/teachers_sec/kyelito/bcr.html), instrumental knowledge

concerning the BCR’s use as a reading comprehension assessment tool as well as

technical knowledge concerning the elements of a BCR (what the three elements of a

BCR are; how to craft a topic sentence; how to write a conclusion, etc.) were ascertained.

A project incorporating BCRs fulfilled all the co-researchers needs.

Collective Development of a Research Design and Methods

Taking into consideration Teacher X’s concerns, Counselor Y’s

recommendations, and the need to involve family and encompass assessment, and after

discussion with the students and some research concerning the nature of BCRs and

reading comprehension, two plans of action were proposed. The first involved detailed

weekly assessment reports sent to family members concerning a breakdown of student

skills in relation to utilization of various reading strategies, including PQ4R (see

Appendix D; from Allen, 2008) and others appearing on their weekly classroom reading

logs (e.g., asking questions and making predictions). The second concerned weekly

practice writing BCRs utilizing a family member with no previous knowledge of the

stimulus text as a reactive audience. The students both preferred the latter. Calling upon

their interactive knowledge, each student chose a family member whom they believed

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

17

would participate and with whom they would feel comfortable working. Girl A chose her

grandmother, with whom she was living at the time, and Girl B chose her mother. The

family members were contacted by telephone to discuss the project (neither family had

internet access at home). Both agreed to participate. Follow-up letters were sent home

with Girls A and B after the next tutoring session, session 3 (see Appendix E), along with

the students’ first BCR assignment.

Collective engagement in research execution

For each of tutoring sessions 3–6, Girl A and Girl B were provided a stimulus text

and prompt taken from the School Improvement in Maryland Website. Stimulus texts and

prompts from both grades 7 and 8 were used. Outside of the tutoring session, the students

were asked to do the following:

Read the prompt.

Read the stimulus text (utilizing PQ4R graphic organizer for support)

Write the BCR.

Give the BCR (but not the stimulus text) to chosen family member to read.

Ask family member to fill out worksheet (see Appendix F).

Revise the BCR using the information provided on the worksheet.

Return worksheet and both versions of the BCR during the next tutoring session.

After week 4, study week 2, students were also asked to do the following directly after

reading the stimulus text (utilizing PQ4R graphic organizer for support):

Compose topic sentence.

Compose conclusion sentence.

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

18

List three textual details supporting the answer you provided in your topic

sentence.

During each successive session, Girls A and B were asked to fill out the weekly followup survey (Appendices G and H). In addition, Girls A and B were provided direct

instruction and guided practice in the following: the elements of a BCR, how to write a

good topic sentence (i.e., include title of stimulus text, author of stimulus text, and

answer to the prompt), how to outline supporting details, how to craft a good conclusion,

and how to utilize reading strategy PQ4R and its accompanying graphic organizer.

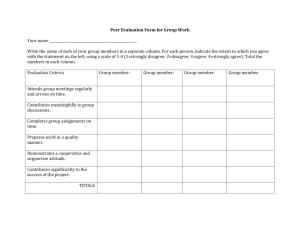

The family worksheet was designed to highlight for the students elements missing

from their BCRs. Items 1–3 concerned the topic sentence. Each item matches an element

that should be present in a topic sentence: item 1, stimulus text title; item 2, stimulus text

author; item 3, answer to prompt. A family member’s inability to provide an answer or

the correct answer should have spurred the student to include the missing element in her

revised BCR. Item 4 concerned supporting details. If a family member indicated

confusion after reading the BCR (e.g., not understanding how the details support the

student’s answer to the prompt), the BCR should have been revised to alleviate this

confusion.

The top portion of the weekly follow-up survey was designed as a multifocus

affective inventory to elicit the student’s perceptions about the BCR and to help indicate

that the BCR score was valid. That is, was the student unable to write a high-quality BCR

because, for example, she did not understand the prompt or because she was unable to

comprehend the text? Future permutations will adhere to the required properties of

multifocus affective inventories as outlined by Popham (2010, pp. 239–242). For

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

19

example, both negative and positive statements relating to each affective variable will be

provided. This will help to ensure student comprehension of the inventory items and

proper interpretation of the student’s answers. Question 5 was designed to assess the

project’s tools. Question 6 was designed to help the student apply higher-order thinking

to her writing.

At the end of the study, the family members were asked to fill out a multifocus

affective inventory concerning their participation in this project. Again, Future

permutations will adhere to the required properties of multifocus affective inventories as

outlined by Popham (2010, pp. 239–242), including assurance of anonymity.

The students were done a disservice during tutoring session 4. In an effort to

make the most efficient use of limited tutoring time, the first round of BCRs they

returned were set aside for later grading. This meant the students received no feedback

before being asked to write another BCR. Because of this mistake, it was decided to

extend the study an additional week. During the following weeks, BCRs were scored and

discussed during the first 15 minutes of the tutoring session. The tutor modeled critiquing

and scoring, the students performed partner critiques, and they all participated in wholegroup discussions.

Part IV: Results and Analysis

Collective Analysis of Data/Results

The project started off well. During the first week of the study, after tutoring

session 3, Girl A wrote two versions of a BCR in response to the prompt: Explain the tone

created by the author's words and phrases in paragraphs 10–12 (see Appendix I for initial and

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

20

revised BCRs, completed family worksheets, and completed student weekly follow-up

surveys; grammatical errors and misspellings are retained as they appeared on the

originals). The first version of the BCR comprised a single sentence, which did not answer the

question implied in the prompt. In addition to turning in a revised BCR, Girl A also turned in

notes outlining the who, what, when, where, and why of the stimulus text, notes created at the

prompting of her family member. The revised BCR was markedly better than the initial BCR, an

improvement not adequately reflected by her scores, which improved from 0 to 1. However, it is

doubtful this improvement was related to use of the family worksheet. Her topic sentence was

still missing the title of the stimulus text, and her details did not adequately address the question

posed by her grandmother on item 4 of the worksheet. In addition, her grandmother read the

stimulus text before filling out the worksheet. Finally, Girl A misunderstood questions 4 and 5 on

the weekly follow-up survey, prompting their revision. While Girl A outlined some good reading

strategies, “go back and circle, underlin, and highlight,” she missed a valuable opportunity to

critique her revisions on a deeper level. In fact, she mentions that she should have included the

author in the topic sentence, but this is something that she actually had done.

Girl B composed an initial BCR but “forgot” to write a second. Her topic sentence does

provide an answer to the prompt, but this answer is incorrect. Moreover, her supporting details do

not corroborate this answer. Despite her mother’s inability to answer questions 1 and 2 on the

worksheet, Girl B failed to revise the BCR to include these elements. Girl B was unable to make a

connection between her mother’s unwillingness to decipher her handwriting and possible

negative effects this handwriting could have on her grades.

During week 2, Girl A again attempted two versions of her BCR. The topic

sentence of the initial BCR contained both the stimulus text title and author’s name;

however, as indicated by her grandmother’s incorrect guess on item 3 on the worksheet, it

did not answer the prompt. Worksheet item 4 focused on grammar rather than content,

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

21

though mention was made about Girl A’s improved ability to summarize. In response,

Girl A’s revision comprised an extended summary retaining the same weaknesses as the

initial BCR. Unfortunately, this version of the BCR was inadvertently retained by the

student after the tutoring session and subsequently misplaced.

Girl B again provided just one version of her BCR, citing her mother’s failure to

provide an answer to worksheet item 4 as having indicated to her that no revisions were

required. However, her mother was unable to provide correct answers to worksheet items

1–3, which should have indicated to Girl B at least the need to revise her topic sentence.

Moreover, during discussion, it was revealed that her mother had orally asked her the

following questions, “What do you think miracle means?” and “How am I supposed to

know the author by reading the BCR?” The latter was an appropriate response to

worksheet item 2, while her actual response to item 2, “The author of the text about

maintain focus on your goal, and put all your energy into achieving it” does not actually

answer the question that was asked. The former should have indicated to Girl B that a

disconnect existed between her and her mother’s concept of miracle, which should have

stimulated her to at least look up the word in the dictionary, an action that should then

have prompted an extensive rewrite of her BCR.

As a result of the students’ failure to fully utilize the family worksheet for their

revisions, during the tutoring session immediately following their turning in of the study

week 2 BCRs, appropriate responses to the worksheet answers were modeled.

Unfortunately, the failure of Girls A and B to participate in the remaining 2 weeks o the

study made determining the effect of this modeling impossible.

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

22

During study week 3 the project started to fall apart. While Girl A arrived for

tutoring, she had an incomplete initial BCR. She indicated that her grandmother had

refused to work on it with her because she had waited until the last minute to begin

working on it. Girl B did not show up for tutoring. Girl A offered to take the week 4

stimulus text, prompt, and family post-study survey (see Appendix J) to Girl B at school.

A follow-up telephone call to Girl B’s mother elicited the following information: Girl B

had been sick the day of the tutoring session and had received the packet from Girl A.

The tutoring session the following week was canceled because of illness. For what turned

out to be the final tutoring session, only Girl B arrived. She had done a BCR for neither

the week 3 nor week 4 stimulus texts or prompts and indicated that she had never

received the latter. This meant that she also did not have a family post-study survey.

The family post-study surveys were conducted by telephone. Both family

members indicated a desire to play a more active role in supporting their student’s

education and agreed that the role they were asked to play during this study was an easy

one to fulfill. They perceived that they understood the role they were being asked to play

and that it did not require too much time.

Collective Decision Making As to How to Use Results and Determine Validity

The results of this study were inconclusive. Development, implementation, and

analysis of this study had to be done in less than 9 weeks. The sample size was too small,

and participation, which was at best sporadic, ended abruptly with the cancellation of the

tutoring sessions, which prevented in-depth discussion with Girl A and Girl B about their

end-of-study self-efficacy in relation to BCRs. Neither Girl A nor Girl B improved the

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

23

quality of their BCRs within this study; the high score was a 1. However, they showed

improvement in their in-class BCRs during this time: Girl A’s scores went from 1 and 1

before tutoring to 2 and E (failure to participate) after tutoring began, while Girl B’s inclass BCR scores improved from 2 and E (failure to participate) to 3 and 2.

Unfortunately, the students’ language arts overall grades did not improve for the grading

quarter concurrent with the study: Girl A received the same grade as she had received

before the study began (D), while Girl B’s grade actually dropped to an E. A close

examination of the students’ grading sheets indicates that these grades may be more

reflective of participation (or lack thereof) than actual ability.

There is some indication that Girl A was motivated by the involvement of her

family in her education, as well as by the individualized attention she received from the

tutor. In response to her grandmother’s attention, Girl A took notes (study week 1: who,

what, where, when, and why), made revisions (study week 2: extended her summary after

reading grandmother’s comment that her ability to summarize had improved),

contemplated use of appropriate reading strategies (study week 2 weekly follow-up

survey), and actively participated in the first two weeks of the study and during the

tutoring sessions she attended, something her grandmother indicated she was not known

for (confirmed by grading sheet). She also experienced a complete failure to participate

after another family upheaval (the return of her mother after study week 2). After study

week 1, Girl A also made a point of staying after the tutoring session to let her tutor know

that the reason she had so many books with her that day was that she was going to go

right to the library to study. She was given additional PQ4R graphic organizers to support

her work.

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

24

While Girl B seemed to pay little heed to her mother’s worksheet answers, she did

seem motivated to share her successes with her tutor. When her short story was selected

for inclusion in a school-wide contest, she brought in the story for the tutor to read. She

also made a point of relating that she had received a 3 on her in-class BCR. However, she

may have benefited the most from personalized instruction in a wholly unexpected

manner. In addition to making comments about the illegibility of her handwriting

(corroborated by her mother on the study week 1 worksheet), which is cramped both

horizontally and vertically, and indicating in what ways this illegibility could adversely

effect her grades, the tutor noticed some other potentially serious issues in relation to her

handwriting. First, Girl B wrote incredibly slowly. Girl A and the tutor could write three

complete sentences before Girl B could finish three words, thus making adequate notetaking in class an impossibility and leaving Girl A disengaged while Girl B caught up.

Second, part of the reason the writing was so slow was that the creation of each curved

letter seemed to require repeated back and forth writing of the top of the curve before the

rest of the letter could be completed: habit, anxiety, or OCD? This handwriting issue was

brought to the attention of the co-researchers.

Post-study discussion with co-researchers resulted in both students being referred

to EEJMS free peer tutoring sessions, held every Tuesday and Thursday at the school.

These sessions are designed to help students complete their assignments in their math and

language arts classes. In addition, Counselor Y and the family members are exploring

other programs and tutoring options to improve the students’ basic grammar, punctuation,

and spelling. Finally, Counselor Y, together with Girl B’s parents, has started an

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

25

investigation into Girl B’s handwriting issues to see whether, and if so what,

accommodations may be warranted.

Ideas for Further Research

A repetition of this research with a larger sample group, and with better access to

self–control group information (i.e., more intimate knowledge of students’ previous

instruction and performance), which could come from more direct and increased input

from the classroom teacher, and with better attention paid to the issue of self-efficacy is

warranted. During the weeks of active participation, some evidence of improvement

specifically in their BCRs but also in reading comprehension in general was seen for both

students. In addition, both benefited from individualized attention, albeit not necessarily

in the manner expected at the beginning of the study, and both families indicated a desire

for more opportunities to play an active role in their students’ education. They liked

receiving direct guidance on how to fulfill such a role (see Appendix K) and felt the role

they were asked to play in this study was easy to understand and not too time consuming.

An increased sample size would contribute to keeping the post-study survey results

anonymous, which may increase the ability to draw accurate inferences from them (see

Popham, 2010, p. 242). In addition, the increased sample size should lead to more

reliable answers, which should also increase the ability to make valid inferences from the

results. On the other hand, increased sample size and anonymity would make following

up on missing surveys, as was done in this study by telephone, impossible.

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

26

Within a classroom, this study could be expanded into a semester-long working

portfolio project. Students would be asked to follow many of the same steps followed by

Girls A and B in this study:

1. Read the prompt.

2. Read the stimulus text (utilizing PQ4R graphic organizer for support)

3. Outline:

a. Compose topic sentence.

b. Compose conclusion sentence.

c. List three textual details supporting the answer you provided in your topic

sentence.

4. Write the BCR.

5. Give the BCR (but not the stimulus text) to chosen family member to read.

6. Ask family member to fill out worksheet.

7. Revise the BCR using the information provided on the worksheet.

8. Return worksheet and both versions of the BCR.

In addition students would be required to outline the revisions made between their initial

and final BCRs, explaining why each was done, and to self-assess their BCRs utilizing

the state BCR rubric. The portfolio would comprise a number of portfolio sets, with each

set consisting of the initial and revised BCRs, the family worksheet, the revision outline,

and the rubric-based scores assessed by both the teacher and student. After the

completion of each portfolio set, conferences would be held between the teacher and

student to discuss differences in rubric scores, BCR strengths and weaknesses, and plans

for future work. At the end of the semester, family members would be invited to view

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

27

their student’s portfolio, to set up a conference with the teacher to discuss the project, and

to complete multifocus affective inventories concerning various aspects of their

participation in the project. Great care would need to be taken in the creation of these

inventories to ensure that they produced the desired information.

The BCR project would be part of a scaffolded macro learning progression

with the final goal of composing a five-paragraph essay.

Macro Learning

Progression

Outline

↓

BCR

↓

Five Paragraph

Essay

The project would be supported in class through direct instruction, modeling, and guided

practice in various aspects of the BCR.

BCR Micro

Learning Strategy

Element Recognition

↓

Topic Sentence

Composition

↓

Conclusion Sentence

Composition

↓

Support Outline

Creation

↓

BCR Composition

In addition, family members would receive training in how to fill out the worksheets and

the implications of their answers to each item.

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

28

References

Allen, J. (2008). More tools for teaching content literacy. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Alvermann, D. E., Phelps, S. F., & Ridgeway Gillis, V. (2010). Content area reading and

literacy: Succeeding in today’s diverse classrooms. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Carter, C. (2010). Ernest Everett Just Middle School: School improvement plan executive

summary 2010–2012. Retrieved from

http://schools.pgcps.org/index.asp?Code=13448

Dewey, J. (2001). Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of

education. In F. Schultz (Ed.), Notable selections in education (3rd ed., pp. 39–

44). Guilford, CT: McGraw-Hill. (Reprinted from Democracy and education: An

introduction to the Philosophy of education, 1916, New York, NY: Macmillan)

Jones, S. M. (2008/2009). Parents can help with the SOLs too. The Virginia English

Bulletin, 58(2), 37–41. Retrieved from http://www.vate.org/veb.htm

Kinsler, K. (1990). Structured peer collaboration: Teaching essay revision to college

students needing writing remediation. Cognition and Instruction, 7(4), 303–321.

Retrieved from http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals/HCGI

Magnifico, A. M. (2010). Writing for whom? Cognition, motivation, and a writer’s

audience. Educational Psychologist, 45(3), 167–184.

doi:10.1080/00461520.2010.493470

Snowman, J., McCown, R., & Biehler, R. (2009). Psychology applied to teaching (12th

ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

White, T. G., & Kim, J. S. (2008). Teacher and parent scaffolding of voluntary summer

reading. Reading Teacher, 62(2), 116–125. Retrieved from

http://www.reading.org/General/Publications/Journals/RT.aspx

Wong, H. K., & Wong, R. T. (2009). The first days of school: How to be an effective

teacher. Mountain View, CA: Harry K. Wong Publications, Inc.

29

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

Appendix A: Parent Consent Form

Dr. Ernest E. Just Middle School

Dear Parent,

As you know, the end of our school year is quickly approaching. As a result, many

students are discovering that they may need additional assistance with various

subjects. Ernest E. Just Middle School and University of Maryland, University

College have formed a partnership to help students receive that assistance. Your child

has been selected to participate in a tutoring program being run by the P.R.I.D.E.

program at Ernest Just Middle School and the University of Maryland University

College. The tutoring program partners teachers at UMUC with students here at

Ernest Just to receive free tutoring. All tutoring sessions will be held at UMUC’s

Largo Campus located at 1616 McCormick Drive, Largo, MD. 20774. If you would

like to participate, please read & sign the front & back of the following registration

form and return to_________________ in the guidance office by Tuesday, February

8th. For questions, please call _________.

REGISTRATION FORM

Student Name: ______________

ID#:_________________________

Subject Designated: ___

Teacher: _____________________

__

Letter Grade (designated course): Quarter 1 ______ Quarter 2 ______

Tutoring will be conducted from 9am-10am on the following dates:

Emergency contact Information:

Parent/Guardian Name: _______________ Telephone No. ____________

Parent/Guardian Name: _______________ Telephone No. ____________

30

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

31

Appendix B: Behavior and Academic Contract

BEHAVIOR AND ACADEMIC CONTRACT

P.R.I.D.E. is committed to academic excellence. The board, faculty, staff, parents,

and students are also committed to our mission to prepare each student for success

both academically and personally.

I, ___________________________, agree to the following condition in order

that I may participate in tutoring sessions held by P.R.I.D.E. and the tutors of

UMUC.

TUTORING PROGRAM EXPECTATIONS:

I will behave appropriately. Students are expected to conduct themselves

in an appropriate manner and follow the code of conduct outlined in the

Student Handbook.

I will attend class. A tutor is not a teacher and attending tutor groups

cannot take the place of classroom attendance. Tutor groups are

supplemental to the classroom experience.

I will attend all tutor groups. Emergencies do arise; however after 2

absences without any communication to the tutor or P.R.I.D.E. director,

the tutee will be dropped from the group.

I will arrive prepared. The tutor is not there to repeat lessons or check

homework. The student needs to do as much of the homework as possible

before the meeting, and come with questions, concerns, problems. So the

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

32

tutor can help him/her gain a better understanding of the material. The

student must bring their textbook, notes, and assignments to every session.

I will be on time. The tutor will be on time and it is expected that the

student will be on time as well. If not, the tutor will start the session

without you.

I will communicate. The student must contact the tutor or P.R.I.D.E.

director regarding late arrivals and absences.

I will be respectful. I will treat tutors and students in a respectful manner

and I will follow directives in a cooperative manner at all times.

It is important that the student abide by these expectations; otherwise, the

student will not receive the full benefit of this arrangement.

_____ I have read and confirm that I understand the terms and conditions of

this contract and agree to abide by the expectations set forth. I understand that

failure to do so will result in my removal from the program.

Student Signature _________________________ Date ______________

Parent/Guardiane Signature ________________ Date ______________

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

33

Appendix C: English Rubric—Brief Constructed Response

English Rubric: Brief Constructed Response

Score 3

The response demonstrates an understanding of the complexities of the text.

Addresses the demands of the question

Uses expressed and implied information from the text

Clarifies and extends understanding beyond the literal

Score 2

The response demonstrates a partial or literal understanding of the text.

Addresses the demands of the question, although may not develop all parts equally

Uses some expressed or implied information from the text to demonstrate

understanding

May not fully connect the support to a conclusion or assertion made about the

text(s)

Score 1

The response shows evidence of a minimal understanding of the text.

May show evidence that some meaning has been derived from the text

May indicate a misreading of the text or the question

May lack information or explanation to support an understanding of the text in

relation to the question

Score 0

The response is completely irrelevant or incorrect, or there is no response.

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

34

Appendix D: PQ4R

PQ4R (From Allen, 2008)

Preview

Question

Read

Reflect

Recite

Review

SAMPLE:

Preview

Question

Preview the text by looking at the title, visuals, headings,

subheadings. Look at how the material is organized and get a

general idea of the content.

Form some questions you have about the content based on the

information you gained during your preview.

Read the material and try to answer the questions you generated.

Think about what you just read by making connections and

applying the information. How does this information match other

information you have on this topic? How would you use this

information? What are the big ideas? What is the “so what?” from

your reading?

Commit the information to memory by stating the main oints

aloud. You could use the headings, bold words, or visuals to

make statements or generate questions. Add to your statements or

answer your questions to help put the information into your longterm memory.

Review the material by generating and answering questions about

the material you have read. You could use this as a time fo

anticipate questions you might be asked when you are being

assessed (tested) on your understanding of the material.

Key concept is highlighted: Planets orbit the Sun at different

distances. Experiment at beginning. Key vocab on left side.

Heading: Planets have different sizes and distances. Subheadings

under: distances, orbits. Review at the end. Picture (p. 80) shows

solar system and distances in the solar system (astronomical AU).

Why do planets orbit the Sun at different distances? How did

planets form? How far is one AU? Do all planets orbit the Sun?

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

35

Appendix E: Follow-Up Letter

Follow-Up Letter

Dear Ms. ______________,

Thank you very much for taking the time to talk to me today about

_______ and how we can work together to help her improve her brief constructed

responses, a skill she will need not only for the upcoming MSAs but also for her

social studies, science, and language arts classes.

A brief constructed response (BCR) is a tool used to assess reading

comprehension. They usually consist of a one-paragraph answer to a question or

prompt about a text the student has been asked to read. The BCR begins with a

topic sentence that should provide a brief answer to the question. The sentences

that follow should provide supporting details for this answer, including evidence

taken from the text and an explanation of how this evidence links back to the

answer. The final sentence should restate the topic sentence or summarize what

the paragraph has been about.

_________, like many students, has trouble supporting her topic

statement. She tends to assume that the reader/grader knows the same information

that she does, so she does not write it out in her BCR. By asking you to be the

audience of her BCR, we are providing _________with a reader she knows has

not read the text. I’m hoping this will help her to be more careful with her details.

Your answers on the worksheet will also provide valuable feedback that will give

her clues to holes she has left in her response.

Each of the next three Saturdays, I will provide __________ with a text

and a question or prompt. She should write her answer and give it to you to read.

Please read it and fill in the accompanying worksheet. After you have filled in

your answers, please give them back to __________ to read. After reading what

you have written, ________ should rewrite her BCR. She should bring both

versions and the worksheet back to me the next week. I will then grade her BCRs

using the same grading scale/rubric that the state will be using on the MSAs that

_________ will be taking in a few weeks. After the third worksheet, I will ask

you and __________ to fill out surveys about how you felt about this process. I

will then write a paper for my class about the experience. I will not use

_________’s name in my paper. If you would like a copy of the final paper, I

would be happy to provide one to you.

Thank you, and I look forward to working with you.

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

36

Appendix F: Family Weekly Worksheet

Family Worksheet

Student’s name _______________________

After reading your student’s brief constructed response (BCR) for this week,

please fill in the following. Your answers should be based only upon the BCR

itself. Afterward, please let your student read your answers. This will provide

them valuable feedback on their response. Your student should then rewrite her

brief constructed response and bring both versions and this worksheet back to me

next week. Thank you!

1. What is the title of the text about which your student is writing?

2. Who is the author of the text about which your students is writing?

3. From the first sentence of the BCR, please guess what question you think the

student is trying to answer:

4. Please list here (and continue on back as needed) any questions or confusion

you have after reading the BCR:

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

37

Appendix G: Weekly Follow-Up Survey

Weekly Follow-Up Survey

Please circle the best answer.

1. I understood the BCR prompt:

strongly

disagree

disagree

neither agree

nor disagree

agree

strongly

agree

neither agree

nor disagree

agree

strongly

agree

agree

strongly

agree

agree

strongly

agree

2. I understood the BCR text:

strongly

disagree

disagree

3. I had trouble reading the BCR text:

strongly

disagree

disagree

neither agree

nor disagree

4. The family worksheet helped me improve my BCR:

strongly

disagree

disagree

neither agree

nor disagree

Please write your answer in the blank provided. You may continue your answer

on the back if you run out of room.

5. Is there anything you would like to see added to the family worksheet? If so,

why?

6. Please detail the revisions you made to your BCR and why you made these

changes.

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

38

Appendix H: Revised Weekly Follow-Up Survey

Revised Weekly Follow-Up Survey

Please circle the best answer.

1. I understood the BCR prompt:

strongly

disagree

disagree

neither agree

nor disagree

agree

strongly

agree

neither agree

nor disagree

agree

strongly

agree

agree

strongly

agree

agree

strongly

agree

2. I understood the BCR text:

strongly

disagree

disagree

3. I had trouble reading the BCR text:

strongly

disagree

disagree

neither agree

nor disagree

4. The family worksheet helped me improve my BCR:

strongly

disagree

disagree

neither agree

nor disagree

Please write your answer in the blank provided. You may continue your answer

on the back if you run out of room.

5. Can you think of anything that your family or teachers could do to help you

write a better BCR?

6. Please list three changes that you made between your first BCR and your

revised BCR and explain why you made each of these changes:

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

39

Appendix I: Results

Week 1

Assigned: February 26, 2011

Due: March 5, 2011

Text: “Scrambled Eggs” by Martha Hamilton and Mitch Weiss (available at

http://mdk12.org/share/assessment_items/resources/scrambled_eggs.html)

Prompt: Explain the tone created by the author's words and phrases in paragraphs 10–12.

Girl A

Initial BCR:

In the text the farmer is trying to get the lawyer to defend him for him eating ten egg and

not paying for it.

Score: _0_

Revised BCR:

Paragraphs 10–12: I think that the tone created by the author, Martha Hamilton is

sarcastic. This story is about a farmer on his way to sell his cattle. The farmer stops at an inn over

night to rest. The next morning the farmer realized he was running short of money and he asked

the innkeeper if he could pay him later for the scambled eggs he at for beakfast but the farmer

forgot to pay after he sold his cattle. Seveal years later the farmer saw the innkeeper and the

innkeeper wanted to charge the farmer four thousand dollars for the eggs he ate because he felt

that the eegs he ate he would produced 10 chickens but the farmer didn’t pay so go a lawyer the

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

40

next day. The lawyer that he got was late to court because he said that he was boiling too bushels

of corn to boil. I knew that you can’t boil corn to grown. I don’t think that scrambled eggs would

produce chickens either and I think that the innkeeper is crazy for thinking that he could get a

chicken out of a scrambled egg.

Score: _1_

Family Worksheet:

After reading your student’s brief constructed response (BCR) for this week, please fill in

the following. Your answers should be based only upon the BCR itself. Afterward, please

let your student read your answers. This will provide them valuable feedback on their

response. Your student should then rewrite her brief constructed response and bring both

versions and this worksheet back to me next week. Thank you!

1. What is the title of the text about which your student is writing? Scrambled Eggs

2. Who is the author of the text about which your students is writing? Martha Hamilton

3. From the first sentence of the BCR, please guess what question you think the student is

trying to answer: She is trying to answer the tone set forth by the author

4. Please list here (and continue on back as needed) any questions or confusion you have

after reading the BCR: Why did the farmer not have to pay his debt

Weekly Follow-Up Survey:

Please circle the best answer. (Student’s answer is bolded here.)

1. I understood the BCR prompt:

strongly

disagree

disagree

neither agree

nor disagree

agree

strongly

agree

neither agree

nor disagree

agree

strongly

agree

neither agree

nor disagree

agree

strongly

agree

2. I understood the BCR text:

strongly

disagree

disagree

3. I had trouble reading the BCR text:

strongly

disagree

disagree

4. The family worksheet helped me improve my BCR:

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

strongly

disagree

disagree

neither agree

nor disagree

41

agree

strongly

agree

Please write your answer in the blank provided. You may continue your answer on the

back if you run out of room.

5. Is there anything you would like to see added to the family worksheet? If so, why?

If my grandma didn’t read the text I would say she could give me a question on how

she would feel about the text and what I could do better.

6. Please detail the revisions you made to your BCR and why you made these changes.

I have to go back and circle, underlin, and highlight the text so that I could understand it

and I should show the author in my topic sentence.

Girl B

Initial BCR:

The tone of paragraphes 10-12 is that the farmer feels sad that he probably won’t win the

case aganist innkeeper. Like a example, the lawyer was late and he said when he came into the

courtroom “I lost track time while I was boiling two bushels of corn and planting them in my

field this morning”. And the judge was outraged by the innkeepers greed and deception. The

judged fined the innkeeper one hundred Kroner/American dollars. I think that if you owe

someone money give them every part of the money if you don’t know when you going to return

back with the rest of the money.

Score: _0_

Revised BCR:

Not done.

Score: _0_

Family Worksheet:

After reading your student’s brief constructed response (BCR) for this week, please fill in

the following. Your answers should be based only upon the BCR itself. Afterward, please

let your student read your answers. This will provide them valuable feedback on their

response. Your student should then rewrite her brief constructed response and bring both

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

42

versions and this worksheet back to me next week. Thank you!

1. What is the title of the text about which your student is writing? Case between farmer

and innkeeper

2. Who is the author of the text about which your students is writing? ?

3. From the first sentence of the BCR, please guess what question you think the student is

trying to answer: What’s the tone of the paragraphe.

4. Please list here (and continue on back as needed) any questions or confusion you have

after reading the BCR: I couldn’t understand her writing. She need to work on

putting space in between her words.

Survey:

Please circle the best answer.

1. I understood the BCR prompt:

strongly

disagree

disagree

neither agree

nor disagree

agree

strongly

agree

neither agree

nor disagree

agree

strongly

agree

neither agree

nor disagree

agree

strongly

agree

agree

strongly

agree

2. I understood the BCR text:

strongly

disagree

disagree

3. I had trouble reading the BCR text:

strongly

disagree

disagree

4. The family worksheet helped me improve my BCR:

strongly

disagree

disagree

neither agree

nor disagree

Please write your answer in the blank provided. You may continue your answer on the

back if you run out of room.

5. Is there anything you would like to see added to the family worksheet? If so, why?

If my grandma didn’t read the text I would say she could give me a question on how

she would feel about the text and what I could do better.

6. Please detail the revisions you made to your BCR and why you made these changes.

Ihave to go back and circle, underlin, and highlight the text so that I could understand it

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

43

and I should show the author in my topic sentence.

Week 2

Assigned: March 5, 2011

Due: March 12, 2011

Text: “Tackling the Trash” by Jill Esbaum (available at

http://mdk12.org/share/assessment_items/resources/tackling_trash.html)

Prompt: The houseboat headquarters for Chad’s team was named The Miracle. Is The Miracle an

appropriate name for the houseboat?

Girl A

Initial BCR:

In the text “tackling the trash” the author Jill Esbaum writes about Chad Pregracke and

how he comes home to see his home town still messy with trash. So he decides to clean it up and

then he raised a lot of money and made it Better, he didn’t Stop until he was done. Then when he

was done he went to other towns in Mississippi and help made them better.

Score: _0_

Revised BCR:

{Student retained and subsequently misplaced.}

Family Worksheet:

After reading your student’s brief constructed response (BCR) for this week, please fill in

the following. Your answers should be based only upon the BCR itself. Afterward, please

let your student read your answers. This will provide them valuable feedback on their

response. Your student should then rewrite her brief constructed response and bring both

versions and this worksheet back to me next week. Thank you!

1. What is the title of the text about which your student is writing? Tackling Trash

2. Who is the author of the text about which your students is writing? Jill Esbaum

3. From the first sentence of the BCR, please guess what question you think the student is

trying to answer: She is telling me about how trashy the Character’s hometown is

and what he does to make it better.

4. Please list here (and continue on back as needed) any questions or confusion you have

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

44

after reading the BCR: This writing is much better in terms of her summary. Her

gramma, punctuation and spelling needs careful attention. She also nees to start

sentences appropriately.

Weekly Follow-Up Survey:

Please circle the best answer.

1. I understood the BCR prompt:

strongly

disagree

disagree

neither agree

nor disagree

agree

strongly

agree

neither agree

nor disagree

agree

strongly

agree

neither agree

nor disagree

agree

strongly

agree

agree

strongly

agree

2. I understood the BCR text:

strongly

disagree

disagree

3. I had trouble reading the BCR text:

strongly

disagree

disagree

4. The family worksheet helped me improve my BCR:

strongly

disagree

disagree

neither agree

nor disagree

Please write your answer in the blank provided. You may continue your answer on the

back if you run out of room.

5. Can you think of anything that your family or teachers could do to help you write a

better BCR?

I think that I could just get a little more help on my vocabulary and making my

pharaghs make more senes.

6. Please list three changes that you made between your first BCR and your revised BCR

and explain why you made each of these changes:

I wrote a little more on the second one not staying on topic.

Girl B

Initial BCR:

I think the miracle is a approprate name for the houseboat because, Miracle means like,

something you trying to do and keep working at it to go to your goal. Like I discovered in the

text, in the middle it said “He spoke at schools, churches and town halls” At the end it said “In

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

45

2000, Chad began hosting community-wide cleanup days in the cities along the Mississippi. I

think that if you trying to reach any goal in your life, work harder and you will get there.

Revised BCR:

Not done.

Family Worksheet:

After reading your student’s brief constructed response (BCR) for this week, please fill in

the following. Your answers should be based only upon the BCR itself. Afterward, please

let your student read your answers. This will provide them valuable feedback on their

response. Your student should then rewrite her brief constructed response and bring both

versions and this worksheet back to me next week. Thank you!

1. What is the title of the text about which your student is writing? I think the title of the

text is about focusing on your goal.

2. Who is the author of the text about which your students is writing? The author of the

text about maintain focus on your goal, and put all your energy into achieving it.

3. From the first sentence of the BCR, please guess what question you think the student is

trying to answer: How to reach your goal?

4. Please list here (and continue on back as needed) any questions or confusion you have

after reading the BCR:

Survey:

Please circle the best answer.

1. I understood the BCR prompt:

strongly

disagree

disagree

neither agree

nor disagree

agree

strongly

agree

neither agree

nor disagree

agree

strongly

agree

neither agree

nor disagree

agree

strongly

agree

2. I understood the BCR text:

strongly

disagree

disagree

3. I had trouble reading the BCR text:

strongly

disagree

disagree

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

46

4. The family worksheet helped me improve my BCR:

strongly

disagree

disagree

neither agree

nor disagree

agree

strongly

agree

Please write your answer in the blank provided. You may continue your answer on the

back if you run out of room.

5. Can you think of anything that your family or teachers could do to help you write a

better BCR?

They can give me some question to make my BCR better than it was before.

6. Please list three changes that you made between your first BCR and your revised BCR

and explain why you made each of these changes:

Week 3

Assigned: March 12, 2011

Due: March 19, 2011

Text: “This Tongue Gets a Grip” by Mariana Relós (available at

http://mdk12.org/share/assessment_items/resources/thistonguegetsagrip.html)

Prompt: What other title would help a reader understand an important idea in this article?

Girl A

Initial BCR:

Refused to turn in. Composed only two sentences.

Revised BCR:

Not done.

Family worksheet:

Not done.

Weekly Follow-Up Survey:

Please circle the best answer.

1. I understood the BCR prompt:

strongly

disagree

disagree

2. I understood the BCR text:

neither agree

nor disagree

agree

strongly

agree

BCRS AND AN UNKNOWING REACTIVE AUDIENCE

strongly

disagree

disagree

47

neither agree

nor disagree

agree

strongly

agree

neither agree

nor disagree

agree

strongly

agree

agree

strongly

agree

3. I had trouble reading the BCR text:

strongly

disagree

disagree

4. The family worksheet helped me improve my BCR:

strongly

disagree

disagree

neither agree

nor disagree

Please write your answer in the blank provided. You may continue your answer on the

back if you run out of room.

5. Can you think of anything that your family or teachers could do to help you write a

better BCR?

No I think that Ms Hayes had been doing a good job.

6. Please list three changes that you made between your first BCR and your revised BCR

and explain why you made each of these changes:

I didn’t really change but if I did I would put in the text This Tongue get a Grip the

question says what other title would help the reader understand the text a little better I