An Autobiography On Louis Armstrong Essay, Research Paper Birth

advertisement

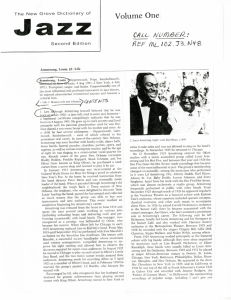

An Autobiography On Louis Armstrong Essay, Research Paper Birth-August 4, 1901, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, Death-July 6, 1971, New York City, New York, USA. It is impossible to overstate Louis ‘Satchmo’ Armstrong’s importance in jazz. He was one of the most influential artists in the music’s history. He was also more than just a jazz musician, he was an enormously popular entertainer and although other black jazz men and women would eventually be welcomed in the upper echelons of white society, Armstrong was one of the first. He certainly found his way into millions of hearts otherwise closed to his kind. Had Armstrong been born white and privileged, his achievement would have been extraordinary; that he was born black and in desperately deprived circumstances makes his success almost miraculous. Armstrong achieved this astonishing breakthrough largely by the sheer force of his personality. Louis Armstrong was born and raised in and around the notorious Storyville district of New Orleans. His exact date of birth only became known in the 90s, although for many years he claimed it to be 4 July 1900, a date which was both patriotic and easy to remember and, as some chroniclers have suggested, might have exempted him from army service. Run-down apartment buildings, many of them converted to occasional use as brothels, honkytonks, dance halls and even churches, were his surroundings as he grew up with his mother and younger sister. His childhood combined being free to run the streets with obligations towards his family, who needed him to earn money. His formal education was severely restricted but he was a bright child and swiftly accumulated the kind of wisdom needed for survival; long before the term existed, Louis Armstrong was ’streetwise’. From the first he learned how to hustle for money and it was a lesson he never forgot. Even late in life, when he was rich and famous, he would still regard his career as a ‘hustle’. As a child, apart from regular work, among the means he had of earning money was singing at street corners in a semi-formal group. Armstrong’s life underwent a dramatic change when, still in his early teens, he was sent to the Colored Waifs Home. The popularly supposed reason for this incarceration, encouraged by Armstrong’s assisted autobiography, was that, in a fit of youthful exuberance he had celebrated New Year’s Eve (either 1912 or 1913) by firing off a borrowed pistol in the street. Whatever the reason, the period he spent in the home changed his life. Given the opportunity to play in the home’s band, first as a singer, then as a percussionist, then a bugler and finally as a cornetist, Armstrong found his m tier. From the first, he displayed a remarkable affinity for music, and quickly achieved an enviable level of competence not only at playing the cornet but also in understanding harmony. Released from the home after a couple of years, it was some time before Armstrong could afford to buy an instrument of his own, but he continued to advance his playing ability, borrowing a cornet whenever he could and playing with any band that would hire him. He was, of course, some years away from earning his living through music but took playing jobs in order to supplement earnings from manual work, mainly delivering coal with a horse and cart. Through his late teens, Armstrong played in many of the countless bands that made their home in New Orleans, gradually working his way upwards until he was in demand for engagements with some of the city’s best bands. The fact that Armstrong’s introduction to music came through the home’s band is significant in that he was inducted into a musical tradition different from that which was currently developing into the newly emergent style known as jazz. The Waif’s Home band played formal brass band music that placed certain demands upon musicians, not least of which were precision and an ornate bravura style. When Armstrong put this concept of music to work with the ideals of jazz, it resulted in a much more flamboyant and personalized musical form than the ensemble playing of the new New Orleans jazz bands. Not surprisingly, this precocious young cornet player attracted the attention of the city’s jazz masters, one of whom, Joe ‘King’ Oliver, was sufficiently impressed to become his musical coach and occasional employer. By the time that Armstrong came under Oliver’s wing, around 1917, the older man was generally regarded as the best cornetist in New Orleans and few challenged his position as ‘the King’. Already displaying signs of great ambition, Armstrong knew that he needed the kind of advancement and kudos King Oliver could offer, even though Oliver’s style of playing was rather simplistic and close to that of other early New Orleans cornetists, such as nearcontemporaries Keppard, Freddie and Buddy Petit. Much more important to Armstrong’s career than musical tuition was the fact that his association with Oliver opened many doors that might otherwise have remained closed. Of special importance was the fact that through Oliver, the younger man was given the chance to take his talent out of the constrictions of one city and into the wide world beyond the bayous of Louisiana. In 1919 Oliver had been invited to take a band to Chicago, and by 1922 his was the most popular ensemble in the Windy City. Back in New Orleans, Armstrong’s star continued to rise even though he declined to stay with Ory when the latter was invited to take his band to Los Angeles. Armstrong, chronically shy, preferred to stay in the place that he knew; but when Oliver sent word for him to come to Chicago, he went. The reason he overcame his earlier reluctance to travel was in part his ambition and also the fact that he trusted Oliver implicitly. From the moment of Armstrong’s arrival in Chicago the local musical scene was tipped onto its ear; musicians raved about the duets of the King and the young pretender and if the lay members of the audience did not know exactly what it was that they were hearing, they certainly knew that it was something special. For two years Oliver and Armstrong made musical history and, had it not been for the piano player in the band, they might well have continued doing so for many more years. The piano player was Lillian Hardin, who took a special interest in the young cornetist and became the second major influence in his life. By 1924 Armstrong and Hardin were married and her influence had prompted him to quit Oliver’s band and soon afterwards to head for New York. In New York, Armstrong joined Henderson, Fletcher’s orchestra, bringing to that band a quality of solo playing far exceeding anything the city had heard thus far in jazz. His musical ideas, some of which were harmonies he and Oliver had developed, were also a spur to the writing of Henderson’s staff arranger, Don (The) Redman. Armstrong stayed with Henderson for a little over a year, returning to Chicago in 1925 at his wife’s behest to star as the ‘World’s Greatest Trumpeter’ with her band. Over the next two or three years he recorded extensively, including the first of the famous Hot Five and Hot Seven sessions and as accompanist to the best of the blues singers, among them Smith, Bessie, Smith, Clara and Smith, Trixie. He worked ceaselessly, in 1926 doubling with the orchestras of Carroll Dickerson and Erskine Tate, and becoming, briefly, a club owner with two of his closest musical companions, Hines, Earl and Zutty Singleton. By the end of the decade Armstrong was in demand across the country, playing important engagements in Chicago, New York, Washington, Los Angeles (but not New Orleans, a city to which he hardly ever returned). By the 30s, Armstrong had forsaken the cornet for the trumpet. He frequently worked with name bands yet equally often travelled alone, fronting whichever house band was available at his destination. He worked and recorded in Los Angeles with Les Hite ’s band (in which the drummer was Hampton, Lionel ), and in New York with Webb, Chick. In 1932 and 1933 he made his first visits to Europe, playing to largely ecstatic audiences, although some, accustomed only to hearing him on record, found his stage mannerisms – the mugging and clowning, to say nothing of the sweating – rather difficult to accommodate. From 1935 onwards Armstrong fronted the Russell, Luis orchestra, eclipsing the remarkable talents of the band’s leading trumpeter, Henry ‘Red’ Allen. In 1938 Louis and Lillian were divorced and he married Alpha Smith. However, by 1942 he had married again, to Lucille Wilson, who survived him. In some respects, the swing era passed Louis Armstrong by, leading some observers to suggest that his career was on a downward slide from that point on. Certainly, the big band Armstrong fronted in the 30s was generally inferior to many of its competitors, but his playing was always at least as strong as that of any of the other virtuoso instrumentalist leaders of the era. His musical style, however, was a little out of step with public demand, and by the early 40s he was out of vogue. Since 1935 Armstrong’s career had been in the hands of Joe Glaser, a tough-talking, hard-nosed extrovert whom people either loved or hated. Ruthless in his determination to make his clients rich and famous, Glaser promoted Armstrong intensively. When the big band showed signs of flagging, Glaser fired everyone and then hired younger, more aggressive (if not always musically appropriate) people to back his star client. When this failed to work out, Glaser took a cue from an engagement at New York’s Town Hall at which Armstrong fronted a small band to great acclaim. Glaser set out to form a new band that would be made up of stars and which he planned to market under the name Louis Armstrong And His All Stars. It proved to be a perfect format for Armstrong and it remained the setting for his music for the rest of his life – even though changes in personnel gradually made a nonsense of the band’s hyperbolic title. With the All Stars, Armstrong began a relentless succession of world tours with barely a night off, occasionally playing clubs and festivals but most often filling concert halls with adoring crowds. The first All Stars included Tea garden, Jack, Barney Bigard , Hines, Earl and Big Catlett, Sid ; replacements in the early years included Young, Trummy, Hall, Edmond, Kyle, Billy and William ‘Cozy’ Cole. Later substitutes, when standards slipped, included Russell Moore, Joe Darensbourg, and Deems, Barrett. Regulars for many years were bassist Arvell Shaw and singer Middleton, Velma. The format and content of the All Stars shows (copied to dire and detrimental effect by numerous bands in the traditional jazz boom of the 50s and 60s) were predictable, with solos being repeated night after night, often note for note. This helped to fuel the contention that Armstrong was past his best. In fact, some of the All Stars’ recordings, even those made with the lesser bands, show that this was not the case. The earliest All Stars are excitingly presented on Satchmo At Symphony Hall and New Orleans Nights, while the later bands produced some classic performances on Louis Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy and Satch Plays Fats. On all these recordings Armstrong’s own playing is outstanding. However, time inevitably took its toll and eventually even Armstrong’s powerful lip weakened. It was then that another facet of his great talent came into its own. Apparent to any who cared to hear it since the 20s, Armstrong was a remarkable singer. By almost any standards but those of the jazz world, his voice was beyond redemption, but through jazz it became recognized for what it was: a perfect instrument for jazz singing. Armstrong’s throaty voice, his lazy-sounding delivery, his perfect timing and effortlessly immaculate rhythmic presentation, brought to songs of all kinds a remarkable sense of rightness. Perfect examples of this form were the riotous ‘(I Want) A Butter And Egg Man’ through such soulfully moving lyrics as ‘(What Did I Do To Be So) Black And Blue’, ‘Do You Know What It Means To Miss New Orleans’, and countless superb renditions of the blues. He added comic absurdities to ‘Baby, It’s Cold Outside’ and over-sentimentality to ‘It’s A Wonderful World’, which in 1968 gave him a UK number 1 hit. He added texture and warmth and a rare measure of understanding often far exceeding anything that had been put there by the songs’ writers. Additionally, he was one of the first performers to sing scat (the improvisation of wordless vocal sounds in place of the formal lyrics), and certainly the first to do so with skill and intelligence and not through mere chance (although he always claimed that he began scatting when the sheet music for ‘Heebie Jeebies’ fell on the floor during a 1926 recording session and he had to improvise the words). It was in his late years, as a singer and entertainer rather than as a trumpet star, that Armstrong became a world figure, known by name, sight and sound to tens of millions of people of all nationalities and creeds, who also loved him in a way that the urchin kid from the wrong side of the tracks in turn-of-the-century New Orleans could never have imagined. Armstrong’s world status caused him some problems with other black Americans, many of whom believed he should have done more for his fellow blacks. He was openly criticized for the manner in which he behaved, whether on stage or off, some accusing him of being an Uncle Tom and thus pandering to stereotypical expectations of behaviour. Certainly, he was no militant, although he did explode briefly in a fit of anger when interviewed at the time of the Civil Rights protests over events in Little Rock in 1958. What his critics overlooked was that, by the time of Little Rock, Armstrong was almost 60 years old, and when the Civil Rights movement hit its full stride he was past the age at which most of his contemporaries were slipping contentedly into retirement. To expect a man of this age to wholeheartedly embrace the Civil Rights movement, having been born and raised in conditions even fellow blacks of one or two generations later could scarcely comprehend, was simply asking too much. For almost 50 years he had been an entertainer – he would probably have preferred and used the term ‘hustler’ – and he was not about to change. Louis Armstrong toured on until almost the very end, recovering from at least one heart attack (news reports tended to be very cagey about his illnesses – doubtless Joe Glaser saw to that). He died in his sleep at his New York home on 6 July 1971. With only a handful of exceptions, most trumpet players who came after Armstrong owe some debt to his pioneering stylistic developments. By the early 40s, the date chosen by many as marking the first decline in Armstrong’s importance and ability, jazz style was undergoing major changes. Brought about largely by the work of Parker, Charlie and his musical collaborators, chief among whom was trumpeter Gillespie, Dizzy, jazz trumpet style changed and the Armstrong style no longer had immediate currency. However, his influence was only sidetracked; it never completely disappeared, and in the post-bop era the qualities of technical proficiency and dazzling technique that he brought to jazz were once again appreciated for the remarkable achievements they were. In the early 20s Louis Armstrong had become a major influence on jazz musicians and jazz music; he altered the way musicians thought about their instruments and the way that they played them. There have been many virtuoso performers in jazz since Armstrong first came onto the scene, but nobody has matched his virtuosity or displayed a comparable level of commitment to jazz, a feeling for the blues, or such simple and highly communicable joie de vivre. Louis Armstrong was unique. The music world is fortunate to have received his outstanding contribution. ED PROW 34e http://ua-referat.com