jqadams_tariff of 1828 - American Studies @ The University of

advertisement

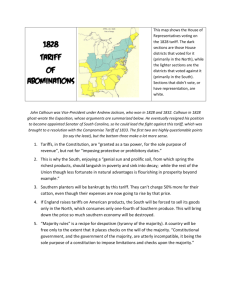

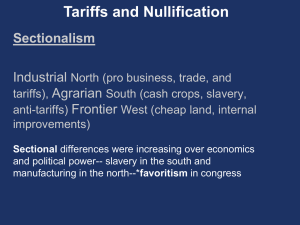

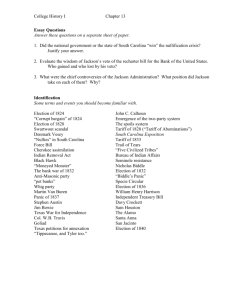

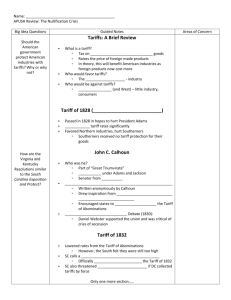

John Quincy Adams (1825-1829) Tariff of 1828 – the "Tariff of Abominations" (April 1828) In 1828 Congress passed and President John Quincy Adams signed tariff legislation designed to protect American manufacturing interests and certain sectors of American agriculture. The legislation severely disadvantaged some sectors of the national economy, most notably southern cotton producers. The Tariff of 1828 was known as the "Tariff of Abominations" in many southern states, and it helped fuel the nullification crisis in South Carolina. The Tariff of 1828 had its origins in the set of economic policies known as the "American System," which were championed by Henry Clay's National Republican faction of the Jeffersonian Republicans. The American System imagined that each section and region of the United States would contribute a different set of raw materials and finished goods, and that, through a system of nationally-funded internal improvements, each section would trade with the other, forming a "home market." For the system to work, certain sectors of the American economy, notably manufacturing, had to be protected from foreign competition. Tariffs kept the prices of foreign manufactured goods artificially high, so that American manufacturers could compete. Southern planters who grew cotton (for which there was only a small American market) felt this system discriminated against them. Southerners succeeded in defeating a small 1827 tariff that would have protected wool producers and woolen manufacturers. Proponents vowed to try again in 1828. The 1828 Tariff grew enormously during legislative action in Congress. Interests such as hemp producers and liquor distillers who feared foreign competition wanted their interests protected, so extra discriminating duties were added. The anti-protection forces succeeded in decreasing some of the protection for woolens, but they also, quite cynically, added additional items to be protected under the tariff. Their plan was to make the tariff so large and ungainly, that even those in favor of a tariff would this particular one repugnant. The plan did not work. Tariff proponents favored some tariff over none at all, and the bill passed both houses of Congress. John Quincy Adams had misgivings about the legislation, but he signed the bill, as the practice at this time was that the president would only veto bills he found unconstitutional, not bills with which he simply disagreed. The Tariff of 1828 came to hurt Adams nonetheless. In the election of 1828, Andrew Jackson won a great deal of support from voters who did not approve of the Tariff. Jackson had been equivocal in his public statements about tariffs, Adams had signed the "Tariff of Abominations." Anti-tariff forces in South Carolina waited until after Jackson was in the White House before they raised the specter of Nullification. That was a crisis for President Jackson. The Tariff of 1828 did set a larger pattern in American politics – southern states would almost uniformly oppose protective tariff legislation through the Civil War. Sources: Mary W. M. Hargreaves, The Presidency of John Quincy Adams (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1985) George Dangerfield, The Era of Good Feelings (New York: Harcourt, Brace, & World, 1952).