86.uncharted waters motion

advertisement

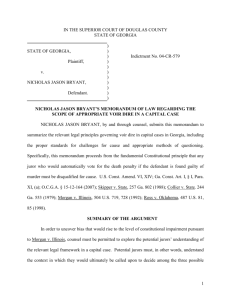

IN THE SUPERIOR COURT OF DOUGLAS COUNTY STATE OF GEORGIA STATE OF GEORGIA, Plaintiff, v. NICHOLAS JASON BRYANT, Defendant. ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) Indictment No. 04-CR-579 MOTION #86: MOTION TO ALLOW COUNSEL TO CONDUCT VOIR DIRE AND TO REMOVE UNDUE RESTRICTIONS ON COUNSEL’S ABILITY TO CONDUCT MEANINGFUL VOIR DIRE NICHOLAS JASON BRYANT, through undersigned counsel, respectfully moves this Court, pursuant to the Fifth, Sixth, Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution, and Article I, § I, ¶¶ I, II, IV, V, VII, IX, X, XI, XII, XIII, XIV, XVI, XVII, XVIII, XXIV and XXVIII of the Constitution of the State of Georgia, to reconsider this Honorable Court’s restrictions on voir dire and to allow the parties to probe potential jurors for potential bias. In support of this motion, counsel states: 1. This Honorable Court, in its October 15, 2007 Order Regarding the Conduct of Voir Dire has directed that counsel shall no longer be allowed to conduct voir dire in the above-captioned capital trial with respect to questioning under Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968) Wainwright v. Witt, 469 U.S. 412 (1985) and Morgan v. Illinois, 504 U.S. 719 (1992). In support of its decision, the Court cites Uniform Superior Court Rule 10.1, which states that “[i]n cases in which the death penalty is sought, the trial judge shall address all Witherspoon and reverse-Witherspoon questions to prospective jurors individually.” 1 2. The scope of voir dire in Georgia is governed by O.C.G.A. § 15-12-133, which states that: . . . In all criminal cases both the state and the defendant shall have the right to an individual examination of each juror from which the jury is to be selected prior to interposing a challenge. The examination shall be conducted after the administration of a preliminary oath to the panel or in criminal cases after the usual voir dire questions have been put by the court. In the examination, the counsel for either party shall have the right to inquire of the individual jurors examined touching any matter or thing which would illustrate any interest of the juror in the case, including any opinion as to which party ought to prevail, the relationship or acquaintance of the juror with the parties or counsel therefor, any fact or circumstance indicating any inclination, leaning, or bias which the juror might have respecting the subject matter of the action or the counsel or parties thereto, and the religious, social, and fraternal connections of the juror. The language of the statute “does not leave the matter to the discretion of the trial judge, but states that the defendant ‘shall’ have the right to an individual examination of each juror prior to interposing a challenge.” Blount v. State, 214 Ga. 433, 434 (1958); see also Edwards v. State, 214 Ga. 436 (1958) (companion case to Blount); Ferguson v. State, 218 Ga. 173, 175 (1962). “[I]t is not within the discretion of the court to deny the right of an individual examination of each juror prior to the interposing of a challenge (citations omitted), nor any other right of examination given under [this statute].” Whaley v. Sim Grady Machinery Company, Inc., 218 Ga. 838, 839 (1963); see also Ladd v. State, 228 Ga. 113 (1971). 3. “Where defendant asserts his right to examine all jurors before striking any of them, it is reversible error for the trial court to deny the defendant that right.” Thomas v. State, 247 Ga. 7 (1981) (citing Ladd v. State, supra, 228 Ga. 113; Ferguson v. State, supra, 218 Ga. 173; Blount v. State, supra, 214 Ga. 433); see also Legare v. State, 256 Ga. 302, 303 (1986) (finding that the defendant in a criminal case “has an absolute right to have his prospective jurors questioned as to those matters specified in O.C.G.A. § 15-12-133”). Denial of this right is presumed harmful, see 2 Hill v. Crowell, 244 Ga. 294 (1979) (finding of harm in civil case), and prejudice need not be shown. Wallace v. State, 164 Ga. App. 642 (1982). 4. To the extent that the Uniform Superior Court Rules are at all in conflict with the Georgia Code and decisions of the Georgia Supreme Court, the Rules must obviously give way. The cases in Georgia explicitly state that it is reversible error in a criminal case to deny a defendant the ability to conduct voir dire of potential jurors. Thomas, supra, 247 Ga. at 7-8. To deny Mr. Bryant the ability to conduct voir dire in this, a capital case, would be to tread upon particularly treacherous ground in light of the mandates of Witt, Witherspoon, and Morgan. Moreover, counsel is personally not aware of any death penalty trial in recent history in the State of Georgia in which the Court has refused to permit the parties to inquire of jurors’ views as they relate to their questions of substantial impairment pursuant to Witt and Morgan. In this respect it is noteworthy that even District Attorney McDade has explicitly stated to the Court that he will not be able to meaningfully exercise his peremptory challenges with only the limited information elicited by the Court’s generic questions. Mr. Bryant therefore renews yet again his objection to the Court conducting all relevant voir dire in this case on the issue of prospective jurors’ views on capital punishment and their ability to follow the law in a death penalty trial. 5. Counsel is still somewhat confused as to what process the Court actually envisions going forward, but as best as they are able to tell, the parties will conduct a preliminary panel voir dire regarding bias not specific to a capital trial, then the Court will question jurors with respect to Witt/Morgan issues, then the parties will be permitted a brief and scripted follow-up on potential jurors’ biases as they relate to capital punishment in panel format. It is improper and will be entirely ineffectual for the parties to question jurors on sensitive and emotional issues regarding their views on capital punishment in a panel format. Potential jurors will be much less likely to 3 open up and express their true feelings in such a format; moreover, some jurors’ views will almost certainly taint previously “qualified” jurors and cause entire panels of venirepersons to be unnecessarily stricken for cause. Counsel therefore objects to the Court’s modified voir dire procedure insofar as it calls for jurors to express their views on the death penalty at least in part in a panel format. 6. The defense further notes once again that the undue restrictions that this Court has placed upon voir dire in this case effectively guarantee that numerous jurors will be qualified and ultimately seated on Mr. Bryant’s jury who are constitutionally impaired under Morgan. In that regard, Mr. Bryant notes that Juror #38, who was disqualified by this Court on October 15, 2007, initially indicated that she would be able to follow the law and consider all three punishments in response to the Court’s generic questioning prior to individual voir dire. After being questioned by the parties, however, Juror #38 unequivocally stated at least 3 times that she could never consider a sentence of life with the possibility of parole for a defendant who has been convicted of malice murder. It became abundantly clear that Juror #38 was laboring under the misconception that she could follow the law only because she did not have any idea what the law actually was when she answered the Court’s initial questions. This same phenomenon of juror confusion is illustrated in the several transcript excerpts that Mr. Bryant has attached as exhibits to his previously-filed motion, entitled Nicholas Jason Bryant’s Memorandum Of Law Regarding The Scope Of Appropriate Voir Dire In A Capital Case [hereinafter Memorandum on Scope of Appropriate Voir Dire]. 7. Counsel has previously laid out the constitutional infirmities that this Court is engendering by inappropriately restricting voir dire in its Memorandum on Scope of Appropriate Voir Dire. The Court is creating further error by refusing to allow counsel to fully probe jurors 4 for bias pursuant to O.C.G.A. §15-12-133. In a capital case, a potential juror is unfit to serve not only if he would automatically vote for the death penalty, but also if he is impermissibly biased in favor of a particular punishment without having heard any evidence. Counsel has been completely precluded from probing the potential punishment biases of potential jurors, and Mr. Bryant’s rights under §15-12-133, as well as his right to effective assistance of counsel under the 6th Amendment, his right to non-arbitrary procedures under the 8th Amendment, and his right to Due Process under the 14th Amendment are all being violated. 8. It is worth final note that counsel has gone out of their way to abide by the Court’s rulings as they relate to conducting voir dire, however the Court continues to cast unfounded aspersions on the conduct and professionalism of defense counsel. Counsel of course recognizes the Court’s role and discretion in conducting an orderly and efficient voir dire proceeding, however such judicial discretion can never be exercised in such a way as to negate Mr. Bryant’s rights under the Georgia and United States Constitutions. WHEREFORE, for these and any such other reasons as may appear to the Court after a hearing on this motion, Nicholas Bryant respectfully moves this Court: 1) to permit defense counsel to conduct voir dire in this case, and; 2) to lift the multiple undue restrictions that this Court has placed upon the scope of voir dire so as not to qualify constitutionally impaired jurors. 5 Respectfully Submitted, ___________________________________ Josh D. Moore, State Bar No. 520028 Office of the Georgia Capital Defender 225 Peachtree Street, NE Suite 900, South Tower Atlanta, Georgia 30303 (404) 739-5156 __________________________________ S. Boyd Young, State Bar No. 142098 Office of the Georgia Capital Defender 225 Peachtree Street, NE Suite 900, South Tower Atlanta, Georgia 30303 (404) 739-5156 6