(final) scope of voir dire brief

advertisement

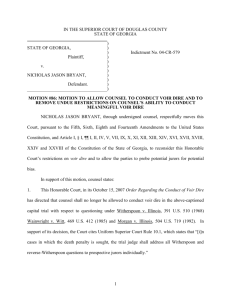

IN THE SUPERIOR COURT OF DOUGLAS COUNTY STATE OF GEORGIA STATE OF GEORGIA, Plaintiff, v. NICHOLAS JASON BRYANT, Defendant. ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) Indictment No. 04-CR-579 NICHOLAS JASON BRYANT’S MEMORANDUM OF LAW REGARDING THE SCOPE OF APPROPRIATE VOIR DIRE IN A CAPITAL CASE NICHOLAS JASON BRYANT, by and through counsel, submits this memorandum to summarize the relevant legal principles governing voir dire in capital cases in Georgia, including the proper standards for challenges for cause and appropriate methods of questioning. Specifically, this memorandum proceeds from the fundamental Constitutional principle that any juror who would automatically vote for the death penalty if the defendant is found guilty of murder must be disqualified for cause. U.S. Const. Amend. VI, XIV; Ga. Const. Art. I, § I, Para. XI, (a); O.C.G.A. § 15-12-164 (2007); Skipper v. State, 257 Ga. 802 (1988); Collier v. State, 244 Ga. 553 (1979); Morgan v. Illinois, 504 U.S. 719, 728 (1992); Ross v. Oklahoma, 487 U.S. 81, 85 (1998). SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT In order to uncover bias that would rise to the level of constitutional impairment pursuant to Morgan v. Illinois, counsel must be permitted to explore the potential jurors’ understanding of the relevant legal framework in a capital case. Potential jurors must, in other words, understand the context in which they would ultimately be called upon to decide among the three possible 1 sentences in a capital trial before they can meaningfully answer the question of whether they would, in fact, be willing to consider all three. Experience and common sense teaches us that jurors often misunderstand the complex legal framework involved. For example, potential jurors often respond that they would be willing to consider a sentence of life with parole only where the “murder” was provoked or was an accident. Such a view on the part of the potential juror – once fully explored by the parties – would plainly render the juror unfit to serve pursuant to Morgan. Such a juror would never meaningfully consider the sentence in the relevant context – the context of a person convicted of malice murder with aggravation. The questioning precluded by this Court is designed solely to address this issue in the most direct and efficient manner possible. Counsel requests leave of this Court merely to explain that in order to reach the sentencing stage of a capital case, the jury would have necessarily determined that the killing was not justified by accident, provocation, self-defense, insanity, or mental retardation. Counsel has no intention whatsoever of running “hypothetical” cases by these jurors and asking them how they would vote. Counsel agrees that pursuant to the law on voir dire in this state, such questions would be improper, but there is nothing “hypothetical” about informing the jurors of the findings they would have necessarily made prior to being faced with the question of sentencing in this case. I. THE FEDERAL AND STATE CONSTITUTIONS DEMAND THAT MR. BRYANT BE TRIED BEFORE A JURY COMPOSED OF INDIVIDUALS WHO CAN GIVE MEANINGFUL CONSIDERATION TO ALL THREE POSSIBLE PUNISHMENTS FOR SOMEONE CONVICTED OF MALICE MURDER. A capital defendant is guaranteed the right to a fair trial before a panel of impartial and indifferent jurors. U.S. Const. Amend. VI, XIV; Ga. Const. Art. I, § I, Para. XI, Sub-section (a); Morgan v. Illinois, 504 U.S. at 728; Ross v. Oklahoma, 487 U.S. at 85; DeYoung v. State, 268 Ga. 780, 782-783 (Ga. 1997). In Morgan v. Illinois, the Supreme Court of the United States 2 confirmed, as it had previously suggested in Ross v. Oklahoma, that in order to protect a capital defendant’s right to a fair trial a juror is properly removed for cause at any stage of the proceedings if it becomes clear that the juror’s views in favor of the death penalty would “prevent or substantially impair the performance of his duties as a juror in accordance with his instructions and his oath.” Morgan, 504 U.S. at 728-729 (quoting Wainwright v. Witt, 469 U.S. 412, 424 (1985)). In Morgan, the Court reiterated that a juror who would “automatically” impose a death sentence following conviction for murder is properly excluded under the substantial impairment standard. Id. at 736. Such automatic death penalty jurors are properly excluded because they “obviously deem mitigating evidence to be irrelevant to their decision to impose the death penalty; they not only refuse to give such evidence any weight but are also plainly saying that mitigating evidence is not worth their consideration and that they will not consider it.” Id.; see also Nance v. State, 272 Ga. 217, 224 (2000) (finding reversible error where a prospective juror, who would automatically vote for a death sentence for all convicted murderers was permitted to serve); DeYoung, 268 Ga. at 783. Put more plainly, a juror is not qualified to serve under Morgan if he or she cannot follow the law. II. MR. BRYANT IS ENTITLED TO A MEANINGFUL VOIR DIRE, WHICH ALLOWS INQUIRY SUFFICIENT TO ENSURE THAT THE JURY IS COMPOSED OF INDIVIDUALS WHO ARE, IN FACT, OPEN TO CONSIDERING ALL THREE PUNISHMENTS FOR A DEFENDANT WHO HAS BEEN CONVICTED OF MALICE MURDER. It is obviously impossible to know whether a prospective juror is able to follow the law in Georgia governing death penalty cases without asking appropriate questions on voir dire. The Court in Morgan specifically held that general questions about a juror’s ability to “follow the law” or to be “fair and impartial” are insufficient to determine whether a potential juror could 3 actually follow the law. The relevant language, directly applicable to our present situation, is as follows: It may be that a juror could, in good conscience, swear to uphold the law and yet be unaware that maintaining such dogmatic beliefs about the death penalty would prevent him or her from doing so. A defendant on trial for his life must be permitted on voir dire to ascertain whether his prospective jurors function under such misconception. The risk that such jurors may have been empaneled in this case and ‘infected petitioner’s capital sentencing [is] unacceptable in light of the ease with which that risk could have been minimized.” Petitioner was entitled, upon his request, to inquiry discerning those jurors who, even prior to the State’s case in chief, had predetermined the terminating issue of his trial, that being whether to impose the death penalty. Morgan, 504 U.S. at 735-36 (quoting Turner v. Murray, 476 U.S. 28, 36 (1986)) (internal citations and footnotes omitted). A “defendant is deprived of due process and his right to an impartial jury if the voir dire procedure is so limited that it cannot uncover prejudice.” Jordan v. Lipman, 763 F. 2d 1265, 1281 (11 Cir. 1985). Thus, the trial court is required to “conduct voir dire of sufficient scope and depth to ascertain any partiality.” Kim v. Walls, 272 Ga. 177, 178-79 (2002). Much like general questions about a prospective juror’s ability to “follow the law” or be “fair and impartial,” a general question about a prospective juror’s ability to consider all three punishments for a defendant who has been convicted of malice murder is similarly unlikely to get at a juror’s true ability to follow the law. A person cannot truthfully know whether he can follow the law unless he knows what that law is, and the term “malice murder” has a specific, technical definition that no juror can reasonably be expected to know or understand. Specifically, as the transcripts attached to this motion as Exhibit A make clear, potential jurors often do not understand that if a defendant has been convicted of malice murder, it means that it was not an accident and that the defendant did not act in self-defense. Indeed, we need look no further than the voir dire that has already been conducted in this case to find a juror who 4 has labored under an honest, but ultimately incorrect, belief that she could consider all three punishments. Potential Juror #29, Virginia Wester initially indicated that she could follow the law and consider all three punishments, but upon learning what it actually meant for someone to be convicted of murder, she stated that under the “technical, legal definition” of murder that she could never consider a sentence of life with parole eligibility. It is also important to view Mr. Bryant’s request to ascertain prospective jurors’ true ability to consider all three punishments in light of the ease with which this can be accomplished. It will take literally 30 seconds per juror to inform them that the jury necessarily will have determined that the killing was not justified by accident, provocation, self-defense, insanity, or mental retardation if they determine that Mr. Bryant is convicted of malice murder in this case. III. MERELY INFORMING POTENTIAL JURORS ABOUT THE CORRECT LEGAL DEFINITION OF MALICE MURDER DOES NOT CALL FOR THEM TO PREJUDGE THE EVIDENCE In questioning potential jurors about their ability to follow the law under the governing legal framework, the defense will in no way be asking potential jurors to prejudge the evidence in the case. The questioning would only go to establish whether the potential juror could truly consider all three punishments, and would not be an inquiry into how he or she would vote in any particular case. The defense fully acknowledges that the latter approach, often termed “staking out,” is prohibited. Blakenship v. State, 258 Ga. 43, 45 (Ga. 1988). (“Neither the Defendant nor the State has the right to simply outline evidence and then ask a prospective juror his opinion of that evidence”). The former approach, however, is not only appropriate, it is constitutionally mandated by Morgan. The reason that the defense’s proposed question does not impermissibly call on potential jurors to prejudge the evidence in this case is because the set of circumstances referenced by the 5 defense would apply in literally every single capital trial that reaches the penalty phase. In other words, the absence of accident, provocation, self-defense, insanity, and mental retardation is not a hypothetical circumstance, but a necessary precondition in order for this case to proceed to the penalty phase. Riley v. State, 278 Ga. 677 (2004) (it is not “prejudgment” for counsel in a death penalty case to question potential jurors if they are “predisposed to a particular sentence for a defendant [not the particular defendant on trial] convicted of murder”). By pursuing the line of questioning herein proposed, the defense is therefore attempting to ferret out potential jurors who would be unqualified to serve in every capital case, not some hypothetical subset of cases. An adequate voir dire enables a capital defendant to exercise his constitutional right to an impartial jury. Without an adequate voir dire, the trial judge’s responsibility to remove prospective jurors who will not be able impartially to follow the court’s instructions and evaluate the evidence cannot be fulfilled. Berryhill v. Zant, 858 F. 2d 633, 640-641 (11th Cir. 1988) (stating that, “[a] thorough voir dire examination is perhaps the most important device to ensure that a jury is impartial.”) (citing Rosales-Lopez v. United States, 451 U.S. 182, 188 (1981)); see also Morgan, 504 U.S. at 729-730; Mu’Min v. Virginia, 500 U.S. 415, 431 (1991). Further, “[a] trial judge should err on the side of caution by dismissing, rather than trying to rehabilitate, biased jurors because, in reality, the judge is the only person in a courtroom whose primary concern, indeed primary duty, is to ensure the selection of a fair and impartial jury.” Foster v. State, 258 Ga. App. 601, 608 (2002); Ivey v. State, 258 Ga. App. 587, 591 (2002); Mulvey v. State, 250 Ga. App. 345, 348 (2001); Walls v. Kim, 250 Ga. App. 259, 260 (2001). IV. CONCLUSION For the forgoing reasons Nicholas Bryant respectfully requests that the Court permit meaningful voir dire so that both the Court and counsel may identify all potential jurors who may 6 harbor any bias with respect to either the guilt-innocence or the penalty phase of the trial. This requires voir dire sufficient to determine whether jurors are predisposed to give the death penalty. Respectfully Submitted, ___________________________________ Josh D. Moore, State Bar No. 520028 Office of the Georgia Capital Defender 225 Peachtree Street, NE Suite 900, South Tower Atlanta, Georgia 30303 (404) 739-5156 __________________________________ S. Boyd Young, State Bar No. 142098 Office of the Georgia Capital Defender 225 Peachtree Street, NE Suite 900, South Tower Atlanta, Georgia 30303 (404) 739-5156 7 EXHIBIT A Transcript #1 Transcript #2 Transcript #3 Transcript #4