AP Ch 19 Summary - Hapenneysocialstudies

advertisement

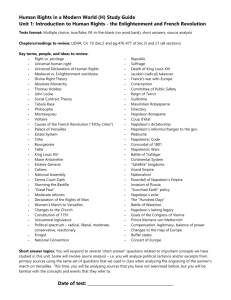

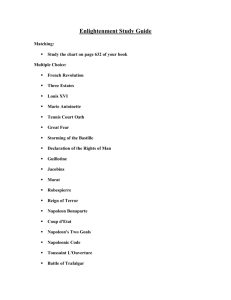

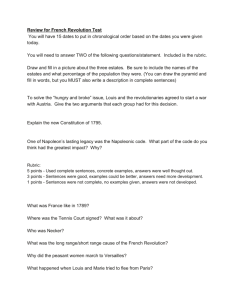

CHAPTER 19 – THE AGE OF NAPOLEON AND THE TRIUMPH OF ROMANTICISM CHAPTER SUMMARY This chapter deals with the period from about 1797–1820 and especially with the figure of Napoleon Bonaparte: his rise to power, campaigns that conquered most of Europe, final defeat, and the settlement reached at the Congress of Vienna. It goes on to discuss Romanticism, a new intellectual movement that spread throughout Europe. The government of the Directory represented a society of recently rich and powerful people whose chief goal was to perpetuate their own rule. Their main opposition came from the royalists, who won a majority in the elections of 1797. With the aid of Napoleon, the anti-monarchist Directory staged a coup d’etat and put their own supporters into the legislature. Meanwhile, Napoleon was crushing Austrian and Sardinian armies in Italy. An invasion of Egypt, however, was a failure. Upon his return (1799), Napoleon led a new coup d’etat and issued the Constitution of the Year VIII, which established the rule of one man and may be regarded as the end of the revolution in France. Bonaparte soon achieved peace with Austria and Britain and was equally effective in restoring order at home. In 1801, he reached an agreement with the pope. In 1802, a plebiscite appointed him consul for life and granted him full power from a new constitution. A general codification of laws called the Napoleonic Code, soon followed and in 1804, Napoleon made himself emperor Napoleon I with yet another constitution. In his decade as emperor (1804–1814), Napoleon conquered most of Europe. He could put as many as 700,000 men under arms at any one time and depended on mobility and timing to achieve the destruction of an enemy army. The chapter next details Napoleon’s impressive victory at Austerlitz (1805), setback at Trafalgar (1805) and defeat of the Prussians and Russians that resulted in the Treaty of Tilsit (1807). Napoleon organized Europe into the French Empire and a number of satellite states—over which ruled the members of his family. To defeat the British, Napoleon devised the Continental System, which aimed at cutting off British trade with the European continent. However, Britain’s other markets (in the Americas and the eastern Mediterranean) enabled the British economy to survive. Napoleon’s conquests stimulated liberalism and nationalism. As it became increasingly clear that Napoleon’s policies were to benefit France rather than Europe, the conquered states and peoples became restive. In 1808, a general rebellion began in Spain (over Napoleon’s deposition of the Bourbon dynasty), and in 1810, the Russians withdrew from the Continental System. The invasion of Russia that followed, along with the disastrous retreat from Moscow in the winter of 1812–1813—exposed French weaknesses. A powerful coalition defeated the French in the “Battle of Nations” (1813). In 1814, the allied army took Paris and Napoleon abdicated, going to the island of Elba. The Congress of Vienna met from September 1814 to November 1815. The arrangements were essentially made by four great powers: Britain, Austria, Prussia, and Russia; the key person in achieving agreement was British foreign secretary Castlereagh. The victors agreed that no single state should dominate Europe. Proceedings were interrupted by Napoleon’s return in March, 1815. They soon defeated him at Waterloo. The episode hardened the peace settlement for France, but the Congress settled difficult problems in a reasonable way. No general war occurred for a century. A new intellectual movement known as Romanticism emerged as a reaction against the Enlightenment. The Age of Romanticism was roughly 1780–1830. Romantic religious thinkers appealed to the inner emotions of humankind for the foundation of religion. Methodist teachings, for example, emphasized inward, heartfelt religion and the possibility of Christian perfection in this life. Romanticism glorified both the individual person and individual cultures. German writers such as Herder and the Grimm brothers went in search of their own past and revived German folk culture. Romantic ideas, then, made a major contribution to the emergence of nationalism by emphasizing the worth of each separate people. Romantic thought also modified European understanding of Islam and the Arab world, helping Europeans to see the Muslim world in a more positive light. 66 OUTLINE I. The Rise of Napoleon Bonaparte A. Early Military Victories B. The Constitution of the Year VIII II. The Consulate in France (1799 – 1804) A. Suppressing Foreign Enemies and Domestic Opposition B. Concordat with the Roman Catholic Church C. The Napoleonic Code D. Establishing a Dynasty III. Napoleon’s Empire (1804 – 1814) A. Conquering an Empire B. The Continental System IV. European Response to the Empire A. German Nationalism and Prussian Reform B. The Wars of Liberation C. The Invasion of Russia D. European Coalition V. The Congress of Vienna and the European Settlement A. Territorial Adjustments B. The Hundred Days and the Quadruple Alliance VI. The Romantic Movement VII. Romantic Questioning of the Supremacy of Reason A. Rousseau and Education B. Kant and Reason VIII. Romantic Literature A. The English Romantic Writers B. The German Romantic Writers IX. Romantic Art A. The Cult of the Middle Ages and Neo-Gothicism B. Nature and the Sublime X. Religion in the Romantic Period A. Methodism B. New Directions in Continental Religion XI. Romantic Views of Nationalism and History A. Herder and Culture B. Hegel and History C. Islam, the Middle East, and Romanticism XII. In Perspective KEY TOPICS Napoleon’s rise, his coronation as emperor, and his administrative reforms 67 Napoleon’s conquests, the creation of a French Empire, and Britain’s enduring resistance The invasion of Russia and Napoleon’s decline The reestablishment of a European order at the Congress of Vienna Romanticism and the reaction to the Enlightenment Islam and Romanticism DISCUSSION QUESTIONS 1. How did Napoleon rise to power? What groups supported him? What were his major domestic achievements? Did his rule fulfill or betray the French Revolution? 2. What regions made up Napoleon’s realm, and what was the status of each region within it? administration show foresight, or was the empire a burden he could not afford? Did his 3. Why did Napoleon decide to invade Russia? Why did the operation fail? 4. What were the results of the Congress of Vienna? Was the Vienna settlement a success? 5. Why did Romantic writers champion feelings over reason? What questions did Rousseau and Kant raise about reason? 6. Why was poetry important to Romantic writers? How did the Romantic concept of religion differ from Reformation Protestantism and Enlightenment deism? How did Romantic ideas and sensibilities modify European ideas of Islam and the Middle East? What were the cultural results of Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt? LECTURE TOPICS 1. Napoleon Bonaparte: Napoleon has been judged as a force for good by some who have viewed him as a law-giver and reformer who spread revolutionary ideals throughout Europe. Others have viewed him as an egomaniac whose lust for conquest and glory overshadowed any other secondary achievements. He was certainly a military leader of genius, but his achievements inspire more philosophical thoughts about the ability of the individual to change the course of history. Is history motivated by economic and social forces over which individuals have no control? Or does the “hero” actually change history by force of personality and ability? The figure of Napoleon is central to that debate, as are such figures as Alexander the Great, Lenin, and Hitler. 2. The Congress of Vienna: In this settlement, the Bourbon monarchy was restored in France and a nonvindictive boundary settlement left France satisfied. The settlement of eastern Europe divided the victors and enabled Talleyrand, representing France, to join the deliberations. France, Britain, and Austria were able to prevent Russia and Prussia from gaining all of Poland and Saxony respectively. The victors agreed that no single state should dominate Europe; the concept of “balance of power” was formally put into practice and proved to be successful for the next hundred years. 3. The Romantic Movement: The immediate intellectual foundations of the movement were provided by Rousseau and Kant. In England and Germany, the term “romantic” came to be applied to all literature that failed to observe classical forms and gave free play to the imagination. English romantics included Blake, Coleridge, Shelley, Wordsworth, and Byron. Perhaps the most important person to write about history at this time was Hegel, who fostered the theory that ideas developed in evolutionary fashion. A predominant set of ideas (the thesis) is challenged by a conflicting set (the antithesis), and out of the conflict emerges a synthesis, which then becomes the new thesis. 68 4. Islam and Romanticism: Under the influence of nationalistic aspirations and romantic sensibilities, Europeans viewed Islam with ambivalence. On the one hand, the Ottoman Empire was reviled as the repressor of independence movements such as the Greek Revolution of 1821; on the other, Europeans viewed the Crusades of the twelfth century through a romantic prism and stories from The Thousand and One Nights were accorded prominence as mysterious and exotic. Napoleon was perhaps the most important individual to reshape Islam and the Middle East in the European imagination. His Egyptian campaign in 1798 opened new opportunities for Europeans to learn about Arabic history and Islamic culture. Two cultural effects on the West of Napoleon’s invasion were an increase in the number of European visitors to the Middle East and a demand for architecture based on ancient models. In the Middle East itself, Napoleon’s invasion demonstrated western military and technological superiority, eventually resulting in Ottoman reforms intended to help the empire compete with European states. SUGGESTED FILMS Napoleon: The Making of a Dictator. Lutheran Church in America. 28 min. Napoleon: The End of a Dictator. Lutheran Church in America. 27 min. The Hundred Days: Napoleon—From Elba to Waterloo. Time-Life. 40 min. The Napoleonic Era. Coronet. 14 min. Goya: The Disasters of War. Radim Films. 20 min. Civilization XII: The Fallacies of Hope. Time-Life. 52 min. Beethoven and His Music. Coronet. 12 min. Empires: Napoleon. PBS. 240 min. Waterloo. Atrium Art. 128 min. Landmarks of Western Art: Romanticism. Kultur Video. 50 min. ATLAS OF WESTERN CIVILIZATION Napoleonic Europe Europe After the Congress of Vienna 1815–1852 TEACHING RESOURCES Images This portrait of Napoleon on his throne by Jean Ingres (1780–1867) shows him in the splendor of an imperial monarch who embodies the total power of the state. Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), “Napoleon on His -Arts, Rennes. Photograph © Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY The Coronation of Napoleon. Jacques-Louis David recorded the elaborate coronation of Napoleon in a monumental painting that revealed the enormous political and religious tensions of that event, which involved the kind of ritual and ceremony associated with the monarchy of the ancient regime. 69 In this early-nineteenth-century cartoon, England, personified by a caricature of William Pitt, and France, personified by a caricature of Napoleon, are carving out their areas of interest around the globe. Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz Nicholas Appert (1749–1841) invented canning as a way of preserving food nutritiously. Canned food could be transported over long distances without spoiling. Private Collection/Bridgeman Art Library Goya y Lucientes, Francisco de Goya, recorded Napoleon’s troops executing Spanish guerilla fighters who had rebelled against the French occupation in The Third of May, l808. Francisco de Goya, “Los fusilamientos del 3 de Mayo, 1808.” 1814. Oil on canvas, 8′6″ 11′4″. © Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid In this political cartoon of the Congress of Vienna, Tallyrand simply watches which way the wind is blowing, Castlereagh hesitates, while the monarchs of Russia, Prussia, and Austria form the dance of the Holy Alliance. The king of Saxony holds on to his crown and the republic of Geneva pays homage to the kingdom of Sardinia. Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz John Constable’s Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows displays the appeal of Romantic art to both medieval monuments and the sublime power of nature. John Constable (1776–1837), “Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows,” 1831. Oil on canvas, 151.8 X 189.9 © The National Gallery, London At the castle of Neuschwanstein, King Ludwig II of Bavaria erected the most extensive neo-gothic monument of central Europe. Josaf Beck/Getty Images, Inc.–Taxi Caspar David Friedrich’s The Polar Sea illustrated the power of nature to diminish the creations of humankind as seen in the wrecked ship on the right of the painting. Kunsthalle, Hamburg, Germany/A.K.G., Berlin/SuperStock John Wesley (1703–1791) was the founder of Methodism. He emphasized the role of emotional experience in Christian conversion. CORBIS/Bettmann Joseph Mallord William Turner’s Rain, Steam, and Speed—The Great Western Railway captured the tensions many Europeans felt between their natural environment and the new technology of the industrial age. Joseph Mallord William Turner, 1775–1851, “Rain, Steam, and Speed—The Great Western Railway 1844”. Oil on canvas, 90.8 X 121.9. © The National Gallery, London When Napoleon invaded Egypt in 1799, he met stiff resistance. On July 25, however, the French won a decisive victory. This painting of that battle by Baron Antoine Gros (1771–1835) emphasizes French heroism and Muslim defeat. Such an outlook was typical of European views of Arabs and the Islamic world. Antoine Jean Gros (1771– 1835). Detail, “Battle of Aboukir, July 25, 1799,” c. 1806. Oil on canvas. Chateau de Versailles et de Trianon, Versailles, France. Bridgeman–Giraudon/Art Resource, NY Maps Map 19–1 THE CONTINENTAL SYSTEM, 1806–1810. Napoleon hoped to cut off all British trade with the European continent and thereby drive the British from the war. Map 19–2 NAPOLEONIC EUROPE IN LATE 1812. By mid-1812 the areas shown in peach were incorporated into France, and most of the rest of Europe was directly controlled by or allied with Napoleon. But Russia had withdrawn from the failing Continental System, and the decline of Napoleon was about to begin. Map 19–3 THE GERMAN STATES AFTER 1815. As noted, the German states were also recognized. 70 Interactive Maps Map 19–4 EUROPE 1815, AFTER THE CONGRESS OF VIENNA. The Congress of Vienna achieved the postNapoleonic territorial adjustments shown on the map. The most notable arrangements dealt with areas along France’s borders (the Netherlands, Prussia, Switzerland, and Piedmont) and in Poland and northern Italy. Timelines NAPOLEONIC EUROPE PUBLICATION DATES OF MAJOR ROMANTIC WORKS Documents NAPOLEON ADVISES HIS BROTHER TO RULE CONSTITUTIONALLY A GERMAN WRITER DESCRIBES THE WAR OF LIBERATION MADAME DE STAËL DESCRIBES THE NEW ROMANTIC LITERATURE OF GERMANY HEGEL EXPLAINS THE ROLE OF GREAT MEN IN HISTORY A Closer Look THE CORONATION OF NAPOLEON 1) What symbolic objects, or markers of power and opulence, do you observe in this painting? 2) Napoleon’s mother did not actually attend the coronation, due to a family feud, but Napoleon ordered David to include her in the image. How does David give the viewer clues both that Napoleon’s mother is an important figure, and that her inclusion in the scene is a fiction? 3) Why do you think David chose to depict this moment, when Napoleon is about to crown his wife Josephine as empress, rather than when Napoleon crowned himself, or later when both he and Josephine were crowned? 4) Although the pope is not portrayed as playing an active role, the physical structure of the church – Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris – takes up an enormous amount of space in David’s composition. Why didn’t David “zoom in” on the human figures at the center of this story? Compare and Connect THE EXPERIENCE OF WAR IN THE NAPOLEONIC AGE ANALYSIS: Zoom to last three lines of first paragraph, l.h. column p. 572, “…jumping over a wall which had given us cover, charged the enemy with a shout which sent the nearest back. . . .” Comment: A little over a century later, in the trench warfare of the first world war, “a shout” would have no impact on opponents armed with machine guns. Zoom to lines 5-6, r.h. column p. 572, “…the enemy very ungenerously continued to fire at me when I was down.” Comment: Note the emphasis on honor – and cool understatement. Zoom to lines 2-3, l.h. column p. 573, “ ‘with God for King and Fatherland’ ” Comment: This Prussian military motto was inscribed on the helmets of German soldiers in World War I. 71 Zoom to lines 13-14, l.h. column p. 573, “Even young women, under all sorts of disguises, rushed to arms” Comment: This phenomenon was not unique to Napoleonic Europe; in the United States Civil War, for example, hundreds of women on both sides disguised themselves as men in order to serve in combat. Web Links Creating French Culturewww.loc.gov/exhibits/bnf/bnf0001.htmlDifferent aspects of French culture as a form of elite power from Charlemagne to Charles de Gaulle are presented by the Library of Congress. Most of the material is from the collections of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Explaining the French RevolutionChnm.gmu.edu/revolution/This site contains an extraordinary archive of key images, maps, songs, timelines, and texts from the French Revolution. The site is authored by Professors Lynn Hunt and Jack Censer, leading scholars in the field of French revolutionary history. Chateau de Versailleswww.chateauversailles.fr/en/Devoted to the history and images of Versailles, this site provides brief essays about the people and events significant to court culture during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It also explores the role of Versailles in French culture after the French Revolution. St. Justhistory.hanover.edu/texts/stjust.htmlTexts by St. Just, a close colleague of Robespierre and a member of the Committee of Public Safety, which orchestrated the Reign of Terror. Modern History Sourcebook: Robespierre: The Supreme Beingwww.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/robespierresupreme.htmlThis site contains Robespierre’s words on The Cult of the Supreme Being and links to other sites. Internet Modern History Sourcebook: French Revolution www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/modsbook13.htmlThis site will direct students to the Modern History Sourcebook section of documents on the French Revolution, Napoleon, and the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleonwww.napoleon.org/en/home.aspSponsored by the Foundation Napoleon for “the furtherance of study and research into the civil and military achievements of the First and Second Empires,” this site is aimed at a nonacademic audience providing chronologies, essays, images and videos, and links to other sites on Napoleon 72