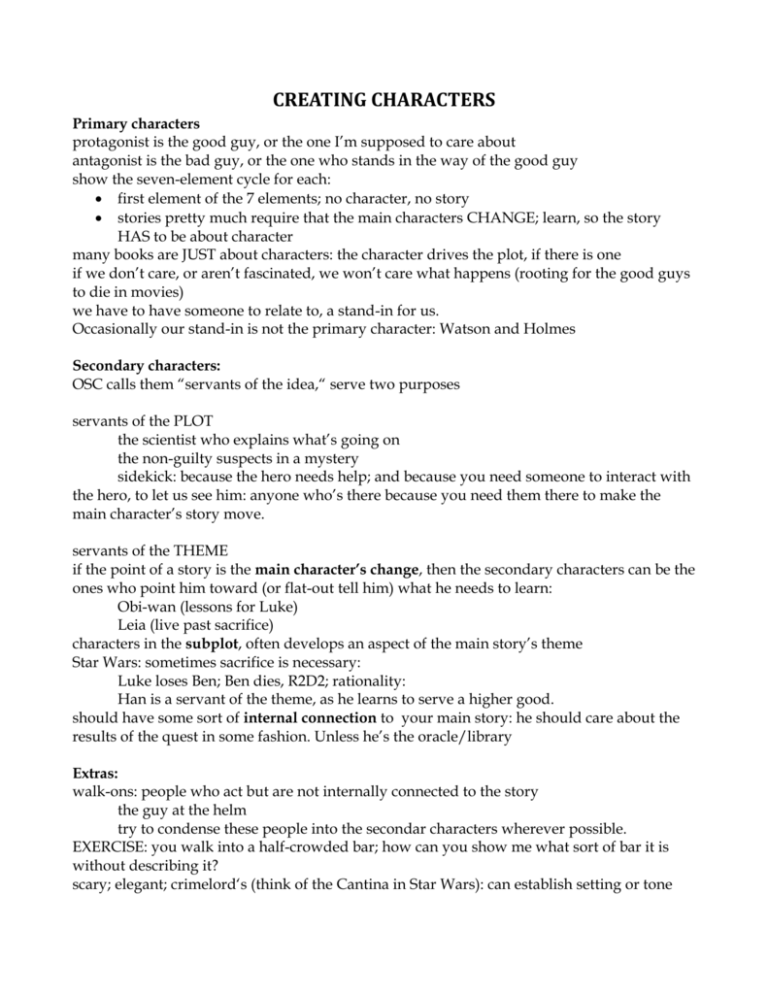

CREATING CHARACTERS

advertisement

CREATING CHARACTERS Primary characters protagonist is the good guy, or the one I’m supposed to care about antagonist is the bad guy, or the one who stands in the way of the good guy show the seven-element cycle for each: first element of the 7 elements; no character, no story stories pretty much require that the main characters CHANGE; learn, so the story HAS to be about character many books are JUST about characters: the character drives the plot, if there is one if we don’t care, or aren’t fascinated, we won’t care what happens (rooting for the good guys to die in movies) we have to have someone to relate to, a stand-in for us. Occasionally our stand-in is not the primary character: Watson and Holmes Secondary characters: OSC calls them “servants of the idea,“ serve two purposes servants of the PLOT the scientist who explains what’s going on the non-guilty suspects in a mystery sidekick: because the hero needs help; and because you need someone to interact with the hero, to let us see him: anyone who’s there because you need them there to make the main character’s story move. servants of the THEME if the point of a story is the main character’s change, then the secondary characters can be the ones who point him toward (or flat-out tell him) what he needs to learn: Obi-wan (lessons for Luke) Leia (live past sacrifice) characters in the subplot, often develops an aspect of the main story’s theme Star Wars: sometimes sacrifice is necessary: Luke loses Ben; Ben dies, R2D2; rationality: Han is a servant of the theme, as he learns to serve a higher good. should have some sort of internal connection to your main story: he should care about the results of the quest in some fashion. Unless he’s the oracle/library Extras: walk-ons: people who act but are not internally connected to the story the guy at the helm try to condense these people into the secondar characters wherever possible. EXERCISE: you walk into a half-crowded bar; how can you show me what sort of bar it is without describing it? scary; elegant; crimelord‘s (think of the Cantina in Star Wars): can establish setting or tone People often use stereotypes for this, which can, in a limited way be useful. Stereotypes and when they’re good: Stereotype: definition? “a conventional or standardized conception or image” Archetype: definition? “the original pattern or model after which a thing is made” Archetypes are often behavior and role related, with mythic overtones: the hero, the princess, the wise teacher. Stereotypes often relate behavior to things a person has no control over: the hot-tempered red-head, dumb Norwegian; the sexually easy Scandinavian; the bookish girl with glasses; math-phobic woman We all know tons of race, age, nationality, gender-related stereotypes. “Isn‘t that just like a _____” This can even apply to aliens: “just like a Klingon.” The good guy should NEVER be a stereotype; should never be an archetype: he may have archetypal characteristics, but he’s supposed to be our stand-in in the story; we need to be able to relate to him: LUKE The bad guy should never be a stereotype; can be an archetype, but then your story will have mythic overtones: DARTH VADER Secondary characters can be archetypes, but should never be stereotypes: BEN, HAN: the internal aspect will help assure that. Extras can be either, but with care: THE BARTENDER Stereotypes are often used because they’re shorthand: Mafia restaurant, I don’t have to explain what sort of people these are, what sort of trouble I’m in. They’re also symbolic when you don’t want to take the time in the story to make real people: a lot of hugely overweight greaseballs with tattoos and motorcycle leathers. NB: Layers of stereotypes CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT Externals: •Appearance: how they look; how they take care of themselves •Voice: how they speak •Mannerisms: how they fiddle, how they move: catlike? nailbiter? •Surroundings: environment: hotel room •Names: don’t pick them out of the phone book, and don’t just pick English names (different # of syllables, different starting and ending letters) Find ways to reflect the character’s internals, or their thoughts using externals using these. Internals: Desires: Understand how your characters’ desires shape their lives (and your story). A story starts when a character wants something: adventure, revenge EXERCISE: character from the story you handed in. What does the central character want? What are her motives for wanting this? Where in the story do you make this clear? How do we learn what she wants? Dialogue? Actions? Thoughts? What or who stands in the way of her getting it? What does her desire set in motion? Fears: What does the central character fear? How does this fear interfere with her getting what she wants in the story? How do we learn about the fear and how it affects her? Background: History: Psychological/family history: a lot of books, they have no family, or a dysfunctional one. Off-stage life: Murder mystery: Patricia Highsmith: the niece and stalkers. Hobbies: what skills has she learned from this hobby and how has it helped her in this story: musician learns to keep trying until you get it right. Relationships: what skills or handicaps has she picked up from her relationships: distrust her instincts. Perception: After everything I said about stereotype, there are still things that a given character will or will not be able to see or do. 70-year-old wind surfer; 12-year-old portrait painter. Often dictated by history, psychological history: a survivor of horrible event CHARACTERS ARE REAL: They will have wants, desires, fears, secrets. They will be in denial about some of these things: they have blind spots. (A perfect opportunity for change in a character across a story) They will have ways to hide their wants. Know how your character is going to change in the story: point the story so that every scene and every interaction with the other main character or the secondary characters force him a step closer to the change, strip another layer of his denial away. TOOLS TO DEVELOP CHARACTERS: The best way to write good characters is to examine yourself unflinchingly, and see how you relate to your wants, fears, and secrets; how you deny them or cope with them. Examine your memories. Observe people: go to the mall or the student union with someone else, and make up histories for the people who walk by. When one of you runs out of ideas, have your friend start, or come up with another story about the person you’re watching. Watch people you know, try to filter out your own feelings about them. Analogy from your own experience. Anger at waiting in line. Know everything about them, even the little stuff: all contradictions and inconsistencies. She is the kind of person who ______. (Answer five to ten times.) Especially useful once you’ve written the story, and are honing the character: Q&A Fix stereotypes by reversing them: Swap age/gender/nationality/race. This forces you to change the character into an individual: hero is a woman, then what’s she like? or a pacifistic Klingon? BUT you must THINK THEM THROUGH THEN. (Often the reverse is also a stereotype: man-hating Amazon)