Endangered Habitat

advertisement

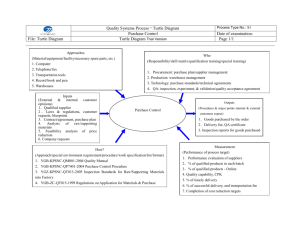

THE SOLUTION This is where you want to focus on solutions that your research suggested may be of benefit to your species along with your own conclusions Your explanation should address the following questions among others. What current conservation efforts are being made that address the problems you’ve already mentioned? o You can mention the efforts of specific groups here and their impact. What can government agencies do to help? What else needs to be done? What solutions does your group suggest and how can others become involved. o You can suggest partnerships with other conservation group’s efforts or o You can design and title your own solutions based on the current efforts being made Concluding Statement Make sure to end with a strong concluding statement that places both a sense of hope and responsibility on the reader. Their action or inaction will make a difference. This is a great place for a strong supporting quotation by one of your sources. This is where you make your final persuasive call to action in the defense of this animal and its habitat. It should clearly show why we should value this animal and be more involved in the efforts to preserve it. A picture in this section is completely optional. If you chose to include one, make sure to reduce the size of this text box so that you don’t copy the picture into it. Works Cited Bessken, Charlene M. "Alligator Snapping Turtle." Endangered Species Guidesheet . 18 Sept. 2004. Missouri Department of Conservation. 17 Feb. 2006 <http://mdc.mo.gov/nathis/endangered/>. Burton, Ken. "Native U.S. Turtles Gain International Protection." U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service News Release 16 Dec. 2005. 20 Feb 2006 http://news.fws.gov/newsreleases/ showNews.cfm?newsId=3432C079-65BF-03E7-2EAF1C827CEA0EE1> Conniff, Richard. "Swamp Thing." National Geographic March 1999: 118 - 129. Dinerstein, E., A. Weakley, R. Noss, R. Snodgrass, K. Wolfe. "Southeastern conifer forests." Wild World. 2001. World Wildlife Fund 2001. 21 Feb. 2006 <http://www.worldwildlife.org/wildworld/profiles/terrestrial/na/na0529_full.html>. Jensen, John, and William Birkhead. "Distribution and Status of the Alligator Snapping Turtle (Macrochelys Temminckii) in Georgia." Southeastern Naturalist 2003: 2. :25-34. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO Host. 19 Feb 2006 <http://web104.epnet.com/>. SECOAST South Eastern Conservation Organization for the Alligator Snapping Turtle Dedicated to the Habitat Preservation and Population Rehabilitation of Macrochelys temminckii, the majestic but elusive Alligator Snapping Turtle. "Macrochelys temminckii." Comprehensive Report. Oct. 2005. NatureServe Explorer. 20 Feb. 2006 <htttp://www.natureserve.org/explorer/servlet >. Reed, Robert N., Justin Congdon, and J. Whitfield Gibbons. The Alligator Snapping Turtle: A review of ecology, life history, and conservation, with demographic analyses of the sustainability of take from wild populations. Aiken : University of Georgia: Savannah River Ecology Laboratory, 2002. <http://www.uga.edu/~srelherp/projects/PDFs/ BobReedAlligatorSnapper-02.pdf> "Southeast Rivers and Streams: Threats to Biodiversity." World Wildlife Fund Technology and Conservation . 2006. World Wildlife Fund. 20 Feb. 2006 <http://www.worldwildlife.org/wildplaces/sers/threats.cfm>. Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, . "Macroclemys temminckii." The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2004. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. 20 Feb. 2006 <http://www.redlist.org/search/details.php?species=12589>. US Fish & Wildlife Service, Department of the Interior. "Inclusion of Alligator Snapping Turtle and All Species of Map Turtle to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, Final Rule." Federal Register 16 Dec 2005: 70.241 :74700-74712.. 19 Feb 2006 <http://www.fws.gov/policy/frsystem/title.cfm >. Image Files Alligator Snapping Turtle Foundation. Feb 20, 2006 <http://www.astfoundation.org/photos.html> Bryant, Richard T. “Alligator Snapping Turtle.” Feb 20, 2006 <http://sherpaguides.com/georgia/flint_river/wildnotes/ graphics/alligator_snapping_turtle.jpg> Friends of the National Zoo. “Alligator Snapping Turtle” Reptiles and Amphibians Smithsonian National Zoological Park Feb 20, 2006 <http://nationalzoo.si.edu/ Animals/ReptilesAmphibians/Meet_the_zoos_herps/default.cfm?id=1> Montgomery, William. “Alligator Snapping Turtle, Macroclemys Temminki Muddy Waters” Valley House Gallery and Sculpture Garden. Feb 20, 2006 <http://www.valleyhouse.com> © 2006 Richard Bryant Range of the Alligator Snapping Turtle Alligator Snappers Need Your Help ! Macrochelys temminckii or the Alligator Snapping Turtle is not the huggable creature that most of us find attractive. As Richard Conniff said it in his March ’99 National Geographic Article Swamp Thing, “You would not put one in a petting zoo unless maybe you wanted the children to learn to count without their fingers”(Conniff 123). It may not be the friendliest of creatures, but it has made its home in the rivers and streams that drain into the Gulf of Mexico for millions of years before man ever stepped foot on this continent. Unfortunately, if decisive action isn’t taken soon, man will be the reason that it disappears from the only place on earth that it naturally exists. © 2005 William Montgomery Alligator Snapping Turtle Man is the sole reason this creature’s future is threatened. Overexploitation and habitat loss have both placed a burden on this species from which it will not recover if we do not do more to regulate its harvest and preserve its natural habitat. ALLIGATOR SNAPPER FACTS Largest fresh water turtle in North America. Lives only in US rivers, lakes, and streams that empty into the Gulf of Mexico. Feeds mainly on fish, but will eat almost anything Spends most of its life in the water leaving only to lay eggs. Females bury large clutches of white hard-shelled eggs in riverbanks every other year. Sex of young is determined by the temperature in the nest Adults reach sexual maturity between 11-13 years and may live more than a century Larger than the common snapping turtle, with a much larger head and a wormlike fishing lure on the surface of its tongue, with which it lures fish directly into its mouth THE HUMAN THREAT Overexploitation and habitat loss are the primary threats to this species; however, commercial harvest for the food and pet industries have taken the most dramatic toll on existing populations of the turtle across its range. Humans have harvested the alligator snapping turtle as a food source for a long time, but the industry increased dramatically in the 60’s and 70’s when the Campbell’s Soup Company began producing frozen turtle soup (Reed et al. 5). In fact, the turtle was such a popular ingredient in soup and picante sauce that some populations were completely wiped out (Conniff 120). The problem with the commercial harvest of this species is that these animals do not reach sexual maturity until they are 11-13 years of age. Research indicates that harvest rates of 2 percent per year of adult females will result in significant © 2005 Alligator Snapping Turtle Foundation Loosely regulated commercial harvesting in Louisiana poses a significant threat to future populations. (Reed et al. 3) population declines (US F & W 74701). In Georgia, three to four tons of alligator snapper were taken annually from the Flint River alone until it could no longer sustain the demand (Reed et al. 5), and TRAFFIC reported in 2000 that over 23,000 live, adult individuals were exported to Hong Kong and Japan for both food and for the pet trade (US F & W 74701). This level of commercial harvest cannot be sustained indefinitely, and although most states within its range offer some protection, Louisiana requires only a fishing license for the unlimited harvest of individuals at least 15 inches in length (Reed et al. 7). At this rate of commercial exploitation, our grandchildren will not know this species unless they read about it. ENDANGERED HABITAT The range of the Alligator Snapping Turtle includes the southeastern coniferous forests and coastal grasslands from Texas to Florida and is limited to the rivers and streams that empty into the Gulf of Mexico. Although it extends as far north as Illinois, very few individuals are still found in the northern extremes of its range. Man has increasingly put pressure on this habitat. The World Wildlife Fund reported in 2001 that over 98% of the southeastern conifer forest has been converted to agricultural use or has been modified by urban development (Dinerstein). Commercial and agricultural development of the turtle’s native habitat as well as river and bankside modifications that reduce nesting areas are greatly contributing to the decline of the species (US F & W 74701). The human population in this region is booming, and along with it comes additional pressures on this habitat. “Runoff, water supply issues, suburban sprawl, unchecked road construction, unsustainable agricultural and forestry practices, dams, mining, and pollution threaten the aquatic life that live beneath regions waters” (Dinerstein). The alligator snapping turtle is part of that mix. The combined effect of the pressure that man has placed on the species through overexploitation and habitat loss is a recipe for the extinction of the species. We have the ability and the responsibility to control that threat.