4. Consultations Overview and Synthesis of Findings

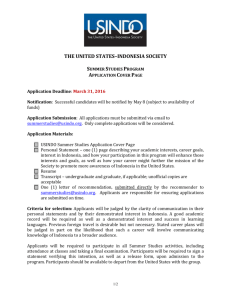

advertisement