The Education of the New Left in Columbia, Missouri

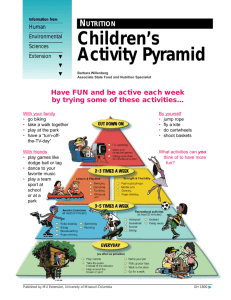

advertisement