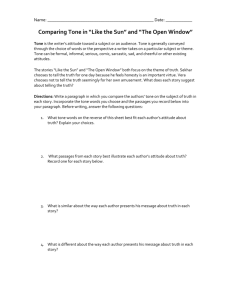

word - Whale

advertisement