independent work of the students

advertisement

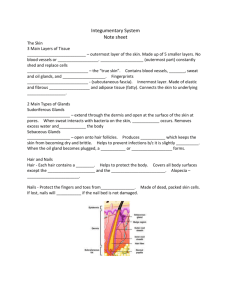

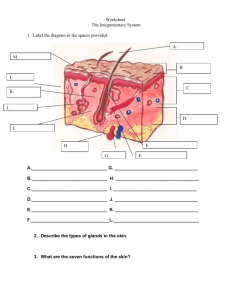

1 Bukovinian State Medical University Department of Developmental Pediatrics METHODICAL INSTRUCTIONS to the practical class for medical students of 3-rd years Modul 1: Child’s development Submodul 2: Topic 4: Subject: PHYSIOLOGICOANATOMICAL FEATURES OF THE SKIN, THE SUBCUTANEOUS FAT AND LYMPH NODES. THE TECHNIQUE OF THEIR EXAMINATION. SEMIOTICS OF THE SKIN DISORDERS. TAKING CARE OF THE CHILDREN WITH THE SKIN DISEASES It is completed by: MD, MSc, PhD Strynadko Maryna Chernivtsy – 2007 2 SUBJECT: Developmental Pediatrics. TOPIC: OBJECTIVES: PROFESSIONAL MOTIVATION: BASIC LEVEL: Basic knowledge of pediatrics. INTEGRATED SKILL ACTIVITY: 1. Care of the children. 2. Anatomy. 3. Histology. 4. Pysiology. STUDENT’S PRACTICAL SKILLS: THE BASIC THEORETICAL ITEMS OF INFORMATION The skin is a complex and important part of the body which plays a large role in the life and health of a child. It has a close physiological connection with the activity of some organs and the organism as a whole. Therefore the skin is the original screen that displays the pathological changes in the organism. A careful examination and an adequate estimation of the condition of the skin have an important role in making a diagnosis of a child's disease. As you remember the skin consists of 3 layers: I. Epidermis which consists of a) corneal layer, b) glassy layer, c) grantilar layer, d) spinous layer, e) basal layer. Basal membrane separates epdermis from the dermis. II. Dermis. III.Subcutaneous tissue. Physiologicoanatomical features of the skin in children The skin in a newborn is velvety smooth, puffy and friable, especially around the eyes, the legs, the dorsal aspect of the hands and feet, and the scrotum or labia. 3 There are some peculiarities of the epidermis in the newborn and young children: In the newborn the epidermis is thinner than in adults. The basal layer is well developed and has 2 kinds of cells -basal and melenocytes. The last ones do not produce melanin until the infant is 6 month. That is why the skin in the newborn is lighter in the first days of life. The grantilar layer is thinner, consists of 2-3 lines of cells It is poorly developed except soles and palms. The absence of keratogliadin protein makes the skin transparent considerably, because keratogliadin protein gives the skin a white hue. The glassy layer is absent. The corneal layer is poorly developed, thin; it has only 2-3 lines of flattened corneal cells. The structure of the corneal layer is friable and puffy. The clinical significance. In newborn and younger children the skin is susceptible to superficial bacterial infection, candidosis (oral moniliasis) and intertrigo with maceration, weeping and erosion. The dermis comprises the major portion of the skin. It is firm, fibrous, and elastic connective tissue network containing an elaborate system of blood and lymphatics vessels, nerves. It varies throughout the body from 1 to 4 mm in thickness. It is invaded by the epidermal downgrowth of hair follicles, sweat and sebaceous glands. The dermis consists of papillary and reticular layers. There are some peculiarities of the dermis in the newborn and young (little) children: In the newborn the papillary layer is poorly developed. In the premature infant it is absent. The dermis has an embryonic structure - it has a lot of cellular elements and a little amount of fibrous structures. Elastic fibres are absent. They first appear in 5-6 months of life. Labrocytes (mast cells) have a high biological activity. In the newborn the quantity of water is higher than in an adult (80 % and 6-8 % respectively) in the dermis. 4 The basal membrane is poorly developed. It leads to easy separation of the epidermis from the dermis, it results in epidermolysis. Morphological maturity of the derma occurs by 6 years. The clinical significance. A newborn and an infant more often show blistering (bullous) reactions caused by the poor adherence between the epidermis and the dermis and frequently affected by chronic atopic dermatitis (eczema). Basic physiological functions of the skin The protective function is an immature function, it occurs because of thin epidermis and dermis, immature basal membrane, a little amount of fibrous structures and a good developing of blood vessels network. The bactericidal function is an immature function, it is due to pH of the newborn skin (6.1-6.7) in an adult pH is acidic (4.2-5.6)). This pH medium is favourable for developing microbes. The thermoregulation is immature function as the result of high emission heat process and immature heat production. The high emission heat processes occur because of a thin skin, a later beginning of sweat glands functioning, a well developed superficial vessel network, the vessels are in physiological vasodilatation. Muscles of the hair bulbs are poor developed, so gooseflesh does not appear. The respiratory function is well developed. It helps immature lungs to perform the respiratory function. The intensity of the respiratory function is more intensive by 8 times in a newborn than in an adult. Well developed respiratory functions are caused by puffy and thin skin, a well developed superficial vessel network, physiological vasodilatation of vessels. The deposition function is well developed. The skin is the depot of blood and water. The reception (receptor) function is well developed. There are a lot of nerves in the skin, so the skin is a peripheral analyzer that grasps endo- and exogenous stimuli. 5 The excretion function is provided by sweat glands. The skin excretes some products of metabolism of fat and carbohydrate and different medicaments. The excretion function of the skin begins with the beginning of functioning sweat and sebaceous glands (3-4 months). The resorption is well developed. It is caused by puffy and thin skin, well developed superficial vessel network, a great number of sebaceous glands and hair follicles. But resorption depends on the chemical structure of the substance: liposoluble substances are well absorbed, water-soluble substances are nonabsorptive. The buffer function is poor developed, because in newborn and young children pH of the skin is nearly neutral (pH 6.1-6.7) therefore the skin can't neutralize acids and alkaline. The pigmentation function is immature. The synthesis of vitamins. The skin synthesizes vitamin D and other biologically active substances. The secretation function. The skin secretes keratin, squalen, calcium and phosphorus. In a newborn the secretion of keratin and squalen is decreased, the secretion of calcium and phosphorus is increased. The metabolic function is well developed, therefore newborns and young children have a high rege-neration of the epidermis and dermis. Physiologicoanatomical features of appendages of the skin in children Appendages of the skin are sebaceous gland, sweat gland, hair. Sebaceous glands are well developed, begin to function since 7-months of the intrauterine life. The quantity of sebaceous glands in 1 cm2 is relatively large in a newborn. Millia is often seen in the newborn. That is the obstruction of the excretory duct of sebaceous glands. Millia localizes on the nose and cheeks, have yellow-roseate color, its size is lxl mm. Millia disappears by 2-3 month. Sweat glands are poorly developed. 6 There are two types of sweat glands: eccrine and apocrine. In a newborn eccrine sweat glands are well formed, but their excretory ducts are feebly developed and obstructed. Eccrine sweat glands begin secretory function by 2 months. Morphological and physiological maturity of eccrine sweat glands occurs by 5-7 years. The formation of apocrine sweat glands finishes by one year but they begin to function only in the puberty period. Hair. The hair covering the skin in a newborn falls gradually during the first year of life instead of permanent hair appearance. With age the hair becomes thicker. Subcutaneous fat. In a newborn the thickness of subcutaneous fat is relatively larger than in an adult (12 % and 8 % in an adult). Distribution of the fat is not regular in a newborn. They have good subcutaneous fat all over the body except the abdomen where there is insensitive deposition during the first 6 months. The subcutaneous fat has an embryonic structure; it gives the possibility to deposit fat and to perform the hemopoietic function. If we look at the chemical structure of the subcutaneous fat we will see the predomination of saturated fatty acids. This gives a good turgor to the skin. The next peculiarity of the subcutaneous fat in the newborn is the presence of a brown adipose tissue. It localizes in the back neck part, in the axillary area, around the thyroid gland and the kidneys, in the intrascupullar space and around great vessels. The main function of the brown fat is heat production without muscle contraction. In 5-6 months the brown fat disappears. The subcutaneous fat is absent in the abdomen, peritoneal and thoracic cavities, therefore the inner organs are movable. The peculiarity of the skin in newborn At birth the skin is covered with grayish-white, cheese-like substance called vernix caseosa. If it is not removed during the first bath, it will dry and disappear in 24 or 48 hours. It is thought to have insulating and bacteriostatic properties. A fine, downy hair called lanugo is present on the skin, especially on the forehead, cheeks, shoulders and 7 back. It usually disappears spontaneously in a few weeks. The technique of the examining of the skin The skin is assessed for color, texture, temperature, moisture, and turgor. Hair is also inspected for color, texture, quality, distribution, and elasticity. The examination of the skin and its accessory organs primarily involves inspection and palpation. Physical factors influencing assessment. The doctor examines the child in a wellilluminated room, with nonglare lighting. Ideally, the room should be neutral in color. Colors such as pink, blue, yellow, or orange cast deceiving glows on the skin. The room should also be comfortably warm, since air-conditioning can cause a coldinduced cyanosis and excessive heat can produce flushing. Poor hygiene and artificial paint on nails or lips also mask the true determination of color. Sometimes it is necessary to clean the skin with soap and water and to remove cosmetics before beginning the inspection. Although not a common situation in pediatrics, the doctor should remembers that such factors can hide the signs of ecchymoses, petechiae, pallor, or cyanosis. Texture, temperature, moisture, and turgor can be subjectively inspected, but palpation must be done for a greater accuracy. Clothing always interferes with palpation, thereby necessitating that the doctor examines each area of the body nude either as the part of the general overall examination or combined with the assessment of each body system. Since texture is affected by climatic exposure, such as cold, sun, wind, and so on, the doctor should compare the texture of the areas of the body that are usually clothed with those that are generally exposed. Genetic factors influencing the assessment of color. The normal color in lightskinned children varies from a milky-white and rosy color to a more deep-hued pink color. In general bluish discoloration or cyanosis is not normal, except in a newborn. Dark-skinned children, such as American Indians, Hispanic, black, Latin, Mediterranean, or Oriental descents, have inherited various brown, red, yellow, olivegreen and bluish tones in their skin, which can falsely alter the assessment. For 8 example, some children of Mediterranean origin normally have bluish-tinged lips, suggestive of cyanosis. Oriental, persons, whose skin is normally of a yellow tone, may appear to be jaundiced. Full-blooded black individuals often have normal bluish pigmentation of the gums, buccal cavity, borders of the tongue, and nail beds. The visible portion of their sclera may contain speckled deposits of brown melanin that resemble petechiae. Physiologic factors influencing the assessment of color. Edema of the skin affects color in all individuals because it increases the amount of interstitial fluid, thereby increasing the distance between the outermost layers of the epidermis and the pigmented and vascular layers. Edema decreases the intensity of the skin color, sometimes, producing a false pallor. Exposure to sunlight, on the other hand, stimulates the melanocytes to produce more melanin, thereby increasing the color of the skin. Individuals who are deeply suntanned require as careful observation as those who are genetically dark skinned. In general the amount of adipose tissue does not markedly affect the skin color because the deposition of fat cells is below the pigmented layers of the skin. However, the doctor should be aware that overnutrition may not mean adequate nutrition, and the observation of pallor that may be indicative of nutritional-iron deficiency should be carefully assessed. Reliable areas for the assessment of color. Color changes are most reliably assessed in those areas of the body where melanin production is least: sclera, conjunctiva, nail beds, lips, tongue, buccal mucosa, palms, and soles. These areas are rarely affected by edema or amount of adipose tissue but are sensitive to changes from physical factors, such as use of cosmetics, ingestion of colored food substances, or poor hygiene. Variations in the skin color. In general color changes of significance include pallor, cyanosis, erythema, plethora, ecchymosis, petechiae, and jaundice. Pallor and cyanosis. The skin receives its pigmented color of yellow, brown, and black from melanin and its shades of red or blue from the color of hemoglobin. 9 Oxygenated hemoglobin in the superficial capillaries of the dermis gives a rosy, pink glow. Reduced (deoxygenated) hemoglobin reflects a bluish tone through the skin, called cyanosis, which is evident when reduced hemoglobin levels reach 5 mg/dl of blood or more, regardless of the total hemoglobin. In general the darker the skin pigmentation is, the greater the amount of deoxygenated hemoglobin must be for cyanosis to be evident. Pallor, or paleness, is evident as a loss of the rosy glow in light-skinned individuals, an ashen-gray appearance in black-skinned children, and a more yellowish brown color in brown-skinned people. It may be a sign of anemia, chronic disease, edema, or shock. However, it may be a normal complexion characteristic or an indication of indoor living. Pallor or cyanosis is most evident in the palpebral conjunctiva (lower eyelid), nail beds, earlobes (mainly for light-skinned children), lips, oral membranes, soles, and palms. Pallor or cyanosis can be compared to the color change normally produced by blanching. For example, in nonpigmented nails, pressing down on the free edge of the nail on the index or middle finger of a child with good skin color produce marked blanching or whitening as compared to the return blood flow. In a child with pallor the difference in color change will be slight. The blanching color change can be observed in dark-skinned individuals by gently applying pressure to their lips or gums. Erythema. Erythema, or redness of the skin, may be the result of increased temperature from climatic conditions, local inflammation, or infection. It may also appear as a sign of skin irritation, allergy, or other dermatoses. The degree of redness reflects the amount of increased blood flow to the area. The doctor notes any reddening and describes its location, size, presence of warmth, itching, type of distribution (diffuse, clearly circumscribed, parallel to a vein, and so on), and the presence of characteristic lesions, such as maculae, papules, or vesicles (see tables 6.1-2). Because erythema is much more difficult to assess in darkly pigmented individuals, the doctor must rely heavily on careful palpating the area for the evidence of associated signs, such as warmth or skin lesions. Primary lesions appear on the nondamaged skin. 10 Secondary lesions come out after primary ones. There are two types of lesions on the skin - primary and secondary. Primary lesions are divided into nonvesicle and vesicle. Plethora. Plethora is also seen as redness of the skin but it is caused by increased numbers of red blood cells as a compensatory response to chronic hypoxia. Intense redness of the lips or cheeks is observed. Ecchymosls and petechlae. Ecchymosis and petechiae are caused by extravasation or hemorrhage of blood into the skin, the only difference between the two is in size. Ecchymoses are large, diffuse areas, usually black and blue in color, and are typically the result of accidental injuries in healthy, active children. Since ecchymotic areas can be indicative of systemic disorders or of child maltreatment, the doctor should always investigate the reported cause of the bruises, especially when they are located in suspicious areas, such as the back or buttocks, rather than on the knees, shins, elbows, or forearms. Petechiae are small, distinct pinpoint hemorrhages 2 mm or less in size, which can denote some type of blood 'disorder, such as decreased platelets in leukemia. Because of their size, ecchymoses are more readily observed than are petechiae, which may only be visible in the areas of very light-colored skin, such as the buttocks, abdomen, and inner surfaces of the arms or legs. They are usually invisible in heavily pigmented skin, except in the oral mucosa, the palpebral conjunctiva of the eyelids, and the bulbar conjunctiva covering the eyeball. The doctor can distinguish the areas of erythema from ecchymosis or petechiae by blanching the skin. Since erythema is the result of increased blood flow to the area, exerting pressure will momentarily empty the engorged vessels and produce blanching. Because the other discolorations are produced by blood leaking into tissue spaces, blanching will not occur. Jaundice. Jaundice, a yellow staining of the skin usually caused by bile pigments, is always a significant finding. It is most reliably observed in the sclera of the eyes in both dark- and light-skinned children, but it may also be evident in the skin, fingernails, soles, palms, and oral mucosa membranes of the latter group. If a yellow-orange cast is 11 noted in an otherwise healthy child, the doctor should inquire about the quantity of ingested yellow vegetables, such as carrots, which in excess produce a yellow-orange color from deposits of carotene in the skin, called carotenemia. The doctor palpates the skin for texture, noting moisture and temperature. Any marks or scars that are suggestive of healed injuries are noted, and inquiries are made about their origin. Normally the skin of young children is smooth, soft, and slightly dry to the touch, not oily or clammy. Any variations from these findings are noted, because they may indicate common problems of childhood such as cradle cap (scaliness on the scalp), eczema (scaliness and desquamation on the scalp, cheeks, knees, and elbows), diaper rash (redness and dryness in the genital area), or excessive dryness (xeroderma) all over the body from too frequent bathing, exposure to the weather, or vitamin-A deficiency. Excessively moist, clammy skin may indicate serious health problems, particularly heart disease. Assessment of the temperature. A doctor evaluates the skin temperature by symmetrically feeling each part of the body and comparing the upper areas with the lower ones. Any distinct difference in temperature is noted. Although not a common anomaly, one of the key signs for coarctation of the aorta is warm upper extremities and cool lower ones. A doctor also observes the skin temperature of the dressed child. Young children produce heat rapidly, and they quickly become overheated if dressed too warmly. Many parents do not realize this and fail to change the amount of clothing to accommodate climatic variations. Assessment of the texture of the skin. A doctor palpates the skin in symmetric spots of the body and in the extremities particularly on the palms and soles and notes their moisture and temperature. Normally the skin of young children is smooth, soft and slightly dry to the touch, not oily or clammy. Assessment of the skin elasticity. It is best determined by grasping the skin on the external surface of the palms or flexor surface of an elbow between a thumb and index finger, pulling it taut, and quickly releasing it. Elastic tissue immediately assumes its normal position without residual marks or creases. In children with poor skin elasticity 12 and turgor the skin remains suspended or tented for a few seconds before slow falling back. Assessment of the skin turgor. It is determined by tension of the soft tissues of the shoulder or the femur with fingers. Normally the doctor must feel flexibility or elasticity of the tissues. The skin turgor and its elasticity are the best estimates of an adequate hydration and nutrition. While evaluating turgor, the nurse also inspects for signs of edema, normally evident as swelling or puffiness. Periorbital edema is a sign of several systemic disorders, such as kidney diseases, but may normally be seen in children who have been crying or sleeping or who have allergies. Edema should be evaluated for change according to position, its specific location, and response to pressure. For example, in pitting edema, pressing a finger into the edematous area will cause a temporary indentation. Accessory organs Hair. The hair is inspected for color, texture, quality, distribution, and elasticity. Children's scalp hair is usually lustrous, silky, strong, and elastic. Genetic factors affect the appearance of hair. For example, the hair of black children is usually curlier and coarser than that of white children. Hair that is stringy, dull, brittle, dry, friable, and depigmented may suggest poor nutrition. Any bald or thinning spots are recorded. Although alopecia can be a sign of various skin disorders, such as tinea capitis, loss of hair in infants may be indicative of lying in the same position and may be a clue for counseling parents concerning the child's stimulation needs. The doctor also inspects the hair and scalp for general cleanliness. Various ethnic groups condition their hair with oils or lubricants, which, if not thoroughly washed from the scalp, clog the sebaceous glands, causing scalp infections. The doctor also inspects hair shafts for lice, whose ova appear as grayish translucent flakes. The doctor can distinguish the ova or nits from dandruff because the eggs adhere to the hair. If 13 pediculosis capitis is suspected, the doctor should be careful to guard against selfinfestation of the lice by wearing gloves, washing the hands after the examination, and standing away from the child when looking through the hair. The doctor also inspects the scalp for ticks, which appear as grayish or brown oval bodies. Although they can be found anywhere on the body, the most common sites are exposed parts, such as the head. Although not all dog or wood ticks transmit serious disease, a notation is made on the child's chart of its removal in case symptoms appear. Unusual hairiness anywhere on the body, such as arms, legs, trunk, or face, is noted. Tufts of hair anywhere along the spine, especially over the sacrum, are significant because they can mark the site of spina bifida occulta. In older children who are approaching puberty, the doctor observes for growth of secondary hair as signs of normally progressing pubertal changes. Precocious or delayed appearance of hair growth is noted because, although not always suggestive of hormonal dysfunction, it may be of great concern to the early- or late-maturing adolescent. Nails. The nails are inspected for color, shape, texture, and quality. Normally the nails are pink, convex in shape, smooth, and hard but flexible, not brittle. The edges, which are usually white, should extend over the fingers. Dark-skinned individuals may have more deeply pigmented nail beds. Variation in color, such as blueness, is suggestive of cyanosis, and a yellow tint may indicate jaundice. Bluish black discoloration usually indicates hemorrhage under the nail from trauma. Fungal infections cause the entire nail to become whitish in color, with a pitting surface. Short, ragged nails are typical of habitual biting. Uncut nails with dirt accumulated under the edge are sometimes an indication of poor hygiene. Changes in the shape of nails are also significant. For example, concave curves or "spoon nails", called koilonychia, are sometimes seen in iron-deficiency anemia, a common nutritional problem of children. Clubbing of the nails is always a significant finding and it is usually associated with chronic cyanosis. In clubbing the base of the nail becomes visibly swollen and feels springy or floating when palpated, rather than 14 firm as in the normal nail. Dermatoglyphics. Each individual has a distinct set of handprints and footprints created by epidermal ridges and creases formed in the third month of prenatal life and cracks that develop subsequently throughout the individual's life-time. The patterns, or dermatoglyphics, are unique to the individual and vary a great deal in detail and complexity of patterns. For example, fingerprint patterns consist of loops, swirls, and arches in highly individualized types and combination. Flexion creases also appear on the palm of the hand and the sole of the foot. The palm normally shows three flexion creases. In some situations the two distal horizontal creases are fused to form a single horizontal crease called a single palmar crease, or simian crease, which is noted in almost all conditions that are caused by chromosomal abnormalities. Another variation noted by some investigators is the Sydney line, in which the transverse palmar crease extends to the ulnar margin of the palm. This is seen in a large percentage children with rubella syndrome. If grossly abnormal lines or folds an observed, the doctor should sketch a picture to describe them an refer the finding to a specialist for further investigation. Assessment of the lymph nodes Lymph nodes are usually assessed when the part of the body in! which they are located is examined. Although the body's lymphatic) drainage system is extensive, the usual sites for palpating accessible lymph nodes are shown in Fig. 6.2. Since the major function of lymph nodes is to collect and filter the lymph of bacteria and other foreign matter as it returns to the circulatory system, a doctor must have knowledge of the lymph's directional flow. Tender, enlarged warm lymph nodes are generally indicative of infection or inflammation proximal to their location. For example, occipital or postauricular adenopathy is often seen in local scalp infection, such as pediculosis, tick bite, or external otitis. Cervical adenopathy usually accompanies acute infections in or around the mouth or throat. In children, however, small, nontender, movable nodes are frequently normal. 15 Nodes are palpated with the distal portion of the fingers, by gently but firmly pressing in a circular motion along the regions where nodes are normally present. When assessing the nodes in the head and neck, the child's head is tilted upward slightly but without tensing the sternocleidomastoid or trapezius muscle. This position facilitates palpation of the submental, submaxillary, tonsillar, and cervical nodes. The axillary nodes are palpated with the arms relaxed at the side but slightly abducted. The inguinal nodes are best assessed with the child in the supine position. Localization, quantity, size, shape, mobility, consistency (elastic or dense), temperature, and tenderness are noted, as well as reports by the parents regarding any visible change of enlarged nodes. Assessment of the skinfold thickness It is examined by grasping the fold of the skin and subcutaneous fat on the abdomen, under the scapula, the shoulder blade and thigh between a thumb and an index finger. Normally the skinfold thickness is 1.5-2.0 cm. Skin disorder syndromes 1. Syndrome of changing the color of the skin and the mucous membranes (symptom of cyanosis, jaundice, paleness and hyperemia). 2. Syndrome of exudative diathesis (maceration, weeping, erosion, scaling, hyperemia, cradle cap). 3. Hemorrhagic skin syndrome (petechiae, hematoma, ecchymosis). 4. Dystrophy syndrome (thin skin, trophic rash, scaling, fissure). 5. Syndrome of injuring the skin (scratches, intertrigo, ulcer, excoriation or erosion, wound). 6. Pigmentation changes syndrome (local or total hyperpigmentation or depigmentation). 7. Moisture changes syndrome (dry skin, wet or mist skin). 16 8. Sensation changing the skin syndrome. 9. Elasticity changing the skin, syndrome. 10. Itching syndrome (total or local). 11. Syndrome of general skin lesions. 12. Syndrome of local skin lesions. The mucous membranes disorder syndromes 1. Fungous damage of the mucous membranes (candidosis, oral moniliasis). 2. Syndrome of inflammation of the mucous membranes (ulcer, erosion, hyperemia, aphtae). The lymph nodes disorder syndromes 1. Hyperplastic syndrome of lymph nodes (local, general). 2. Lymphadenitis (local, general). The subcutaneous fat disorder syndromes 1. Syndrome of sclerema. 2. Syndrome of sclerederma. 3. Syndrome of decreased turgor. 4. Syndrome of decreased trophy (local, general (anasarca)). 5. Syndrome of excessively developed fat (paratrophy, obesity). 6. Syndrome of edema (total, local). 7. Syndrome of thickening (infiltration) of subcutaneous fat. 8. Syndrome of myxedema. Appendages of the skin disorder syndromes Hair disorders syndromes 1. Alopecia syndrome (universal, circumscribed). 2. Hypertrichosis or hyrsutism (excessive pilosis). 17 3. Hypotrichosis. 4. Dystrophic disorders of hair (thin hair, tailing of hair, fragility of hair, lusterless of hair). 5. Syndrome of untypical growth of hair. Nails disorders syndromes 1. Dystrophic disorders of nails: a) micotic lesion; b) trauma; c) congenital disease. 2. Syndrome of inflammation of nail. 3. Nail dysplasia. 4. Deformation of nails syndrome (congenital, acquired). INDEPENDENT WORK OF THE STUDENTS: Make a general conclusion on a theme of a class №1 and conducted practical work. REVIEW QUESTIONS: TEST PROBLEMS Situation tasks. REFERENCES: 1. Nursing care of Infants and Children / editor Lucille F. Whaley and I. Wong. Donna L. - 2nd ed. - The C.V. Mosby Company. - 1983. - 1680 p. 2. Nykytyuk S.O. et al. Manual of Propaedeutic Pediatrics. – Ternopil: TSMU, 2005. – P. 6-22. 3. Pediatric Nurse Practitioner Certification Review Guide / editor, Virgina layng Milloing: contributing authors, Ellen Rudy Clore and all. - 2nd ed. - Health Leadership Associates,Inc.,1994. - 628 p. 4. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics / edited by Richard E. Behrman, Robert M. Kliegman, Ann M. Arvin; senior editor, Waldo E. Nelson - 15th ed. - W.B.Saunders Company, 1996. - 2200 p. 5. Whaley L.F., Wong D.L.: Nursing care of infants and children, St. Louis, Toronto, London, 1983.