Ife WL2 - Nevermindthebllcks

advertisement

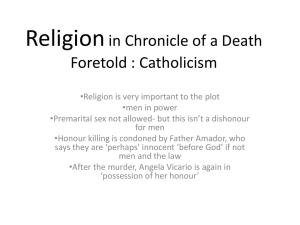

Olowosusi Ifeoluwapo 001412008 Language A1 English HL World Literature Paper 2 Word Count: 1133 The quest for the regeneration of honor in For Whom the Bell Tolls and Chronicle of a Death Foretold In societies governed by religious piety, chastity is deemed to be the most important virtue especially for women. In For Whom the Bell Tolls and Chronicle of a Death Foretold, Maria and Angela Vicario live in a catholic society where honor is perceived as a woman’s ideal identity. However, both women still manage to lose their honor. Maria in For Whom the Bell Tolls, suffers physical and emotional trauma when she is brutally raped and forced to watch her parents being murdered during a fascist raid in Valladolid, her hometown. Angela Vicario, in Chronicle of a Death Foretold, suffers from several physical scars after her family finds out that she lost her virginity before marriage. In the end, the protagonists are left in a state of despair and are forced to dwell on other character’s compassion to regain their inner strength and to regenerate their honor. The loss of innocence in both novels is accompanied by physical scars. The first time Maria meets Robert Jordan, she is ashamed to reveal herself to him because she is physically scarred. The signs of the brutal rape was not only evident emotionally but was also present physically. Maria shaved her head bald not only to obviously signify the recent trauma she has been through but also to signify the mourning of a ‘lost treasure’, which is her honor (Hemingway 23). At the sight of seeing Maria, Robert “saw the strange thing about her” (22). Maria would have been “beautiful if [the fascists] hadn’t cropped her hair” (22). Maria’s loss of honor serves to conceal and dull her natural beauty (Hemingway 23). In Chronicle of a Death Foretold, the tainting of Angela Vicario’s honor led to excessive beating from her family. Angela’s “face was all bruised” and “her satin dress was in shreds” (Marquez 47, 46). Furthermore, Pura Vicario (Angela’s mother) was “holding [Angela] by the hair with one hand and beating [her] with the other with such a rage” enough to utterly reshape Angela’s appearance (47). It was impossible to believe that Angela Vicario, the once ideal paragon of what a woman should be, “would end up resembling bad literature so much” (89). The reaction from Angela’s family indicates the importance of honor in Angela’s society. In addition, Angela’s honor is of utmost importance even to herself that she was even “half in mourning” twenty-three years after the incident (89). Hence, the loss of honor serves to hurt and weaken Angela not only physically but also emotionally. Similarly to Maria, Angela remains as the emissary of pity after her honor is taken away. The period of mourning is both crucial and vital to both characters as this precedes their eventual healing process. Maria’s healing process begins with her relationship with Robert Jordan, while Angela’s lies in the letters in which she sends to Bayardo San Roman, the man she was married to for a night. Maria is vulnerable but she still exudes resilience that helps her cope with the trauma of the rape and the desensitizing Spanish civil war. This resilient nature stems from the love derived from her relationship with Robert Jordan. Maria is healed instantaneously the first time she has sexual intercourse with Roberto. She became “fresh, new and smooth and young and lovely” again after making love (Hemingway 73). The author even uses earth imagery when referring to Maria to signify her newly evolved persona. She is compared to “the golden brown of a grain field” and her breasts to “small hills” (22). Maria has therefore regained her sense of belonging and identity as her emotional bruises are exchanged for pure love in the Robert Jordan’s heart. Angela Vicario, similarly to Maria, is also healed after the mourning phase. However, unlike Maria, Angela regenerates her honor through the letters she sends to Bayardo San Roman. Angela remains an enigmatic character till the end as she never gives a reason or proof as to why Santiago Nasar is the man responsible for taking away her honor. Angela starts the “conventional missive” after she caught a glimpse of Bayardo San Roman whilst waiting outside a hotel (Marquez 93). Soon enough, the thought of Bayardo turned slowly into an obsession, a necessity. She writes the first letter to him and soon after “she wrote a weekly letter for over a lifetime” (94). Despite the fact that Bayardo never replied, the “only thing that didn’t occur to [Angela] was to give up,” even though “it was like writing to nobody” (95). Traditionally, love letters serves to “express emotion and covey longing” (Sparknotes). However, Bayardo shows that “the repeated act of sending a love letter, rather than the love letter's actual content, demonstrates the love that Angela feels for him” (Sparknotes). Angela’s obsession with letters to Bayardo becomes a ritual, which serves as a symbol to regenerate her lost honor. The final letter she writes to Bayardo is twenty-pages long and she believed that this will mark the “end of her agony” (95). In essence, the pain of “her lost possession” is alleviated when Angela’s loved one return (38). Maria in For Whom the Bell Tolls and Angela in Chronicle of a Death Foretold are characters bound to bear the pain caused by the loss of innocence. In the end, they fully recover and regain their sense of identity. Furthermore, in their quest to regenerate their honor, they change those that hold the key to their total healing. Maria, whilst recovering from emotional and physical trauma, serves as the “impetus for Robert Jordan’s personal development” (Spark notes). As the novel commences, Robert Jordan firmly states in a conversation with General Golz that he has no time for women. Furthermore, even as his relationship with Maria develops into something more profound, Jordan still shuts Maria out when he must think of work. However, at the end of the novel (due to Maria’s love), Jordan forms a parallel between his love for Maria and his commitment to the cause. Similarly, Angela Vicario’s letters does reawaken in Bayardo the emotions he felt for her (Angela) prior to the wedding night. Due to her obsessive letter writing, Bayardo is able to see past the fact that ‘his woman’ has lost her honor. Furthermore, Angela’s ritual has transformed Bayardo from the “enchanting” and outgoing person into a “fat” emissary of pity (Marquez 25, 96). In spite of both characters loss of chastity, both still regain their sense of identity as they aim to regenerate their honor through emotional healing. Maria becomes symbolic as she becomes the “emblem of a land that maintains its beauty, strength, dignity in face of forces that threaten to tear it apart” (Sparknotes). Angela Vicario takes upon herself to be the “mistress of her fate” and hence “became a virgin again” just for the one she loves (Marquez 94). Work Cited Page “Chronicle of a Death Foretold.” Sparknotes. 19 Feb. 2009. <http://www.sparknotes.com/lit/chrondeath/section4.rhtml> “For Whom the Bell Tolls.” Sparknotes. 20 Feb. 2009. <http://www.sparknotes.com/lit/belltolls/canalysis.html> Hemmingway, Ernest. For Whom The Bell Tolls. New York: Scribner, 2003 Marquez, Gabriel Garcia. Chronicle of a Death Foretold. London: Penguin books, 1996