Chapter 2

Rights-holders and duty-bearers ........................................................... 3

Negative and positive rights ................................................................... 6

First and second generation human rights.......................................... 8

Does the negative-positive distinction hold? ....................................10

Assigning responsibility: causality and morality ......................................12

Extent - universal rights and universal duties ...........................................16

Universal rights and special rights .....................................................16

Universal duties and limited duties .....................................................18

From rights to duties – disanalogy properties .................................20

Alienability - inalienable and optional rights ....................................23

Strength – fulfilment, abrogations and prima facie duties .............24

1

Chapter 2: rights, duties and universality

The concept of right is central to an investigation of the limitations of universal duties, as the locus of duties. Alas, perhaps exactly because rights occur in and are central to several different contexts (ethical, juridical and political), and because it is a concept that is treated by very different theoretical approaches, it is given many different meanings.

1 Often, as Shelly Kagan points out, it means simply that something has moral value – that its interests must be included in the consideration of which actions are justified: “In what is probably the broadest sense of the term, to say of something that it has moral rights is only to say that it has moral standing – that it counts from the moral point of view. […] In this broad sense of the term, therefore, every normative theory believes in the existence of rights.” (Kagan, 1998, p.170f) But in a more specific sense there are limitations to what can count as a right and how rights can function, which influence the crucial issue of what duties follow from them.

In this chapter I will try to present a relatively abstract and formalistic concept of right, focusing on the meaning of the term in an ethical context.

2 I then argue that universal rights generate extensive duties, and that one of the prominent ways of limiting the burden this places on duty-bearers, the distinction between positive and negative rights and duties, is untenable. Finally, I examine what it means for a

1 Shelly Kagan thus waits until halfway through his work on normative ethics before introducing the concept, and explains this delay by stating: “The reason is that talk of rights, although perfectly legitimate, is horrendously ambiguous . The simple fact of the matter is that people mean a large number of different things when they talk about rights.” (Kagan, 1998, p.170)

2 I should stress that many of the traits that I here deal with in relation to rights, apply to normative ethics in general, with slight variations. When I say e.g. that a right requires a rights-holder, I do not mean to imply that this is a unique trait of a rights-oriented ethics. Only that it is a necessary part.

2

duty to be universal, and clarify how the extent of a duty differs from its alienability and strength. These clarifications will become important in the analysis of the different suggestions for how to limit the extension of the duties generated by rights that follow in chapters 4 and 5.

1.1

What is a right?

The traditional way of conceiving rights focuses on the autonomy of the individual and the claims that can be made on the basis of this autonomy. These claims will often be conceived as demands for other moral agents not to interfere with the choices or options of the individual holding the right. Thus, in line with this conception, “the formula that ‘P has a right to do X’”, is described by Waldron as consisting of three parts: “(1) that others have a duty not to prevent P from doing

X, (2) that the point of such duty is to promote or protect some interest of P’s, and

(3) that although it is a matter of self-interest, P should feel no embarrassment about insisting upon and enforcing this duty.” (Waldron, in: Goodin and Pettit

(eds.), 2001, p.575f)

As Waldron points to, an important constitutive part of the concept of right is the concept of duty – the idea that rights produce ethical claims that bind other moral agents and limit the actions that they can legitimately take: “The analysis I have just provided indicates that rights are correlative to duties, so that talking about rights is a way of talking about people’s responsibilities.” (Waldron, in: Goodin and Pettit

(eds.), 2001, p.576) generate

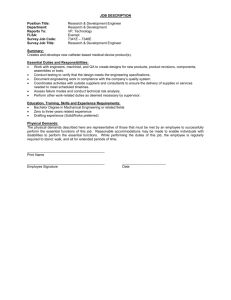

Rights Duties towards

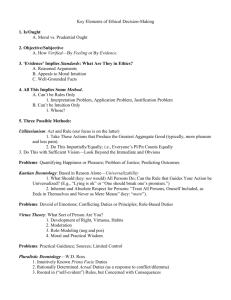

Fig. 1: Rights generate duties towards those who hold them

1.1.1

Rights-holders and duty-bearers

The first and most obvious trait of a right is that it is attached to a rights-holder.

This means that a right presupposes a moral agent who is equipped with the right,

3

and who can use it to raise some type of demand, in some form or other, against other moral agents.

3 The natural rights-holder in most ethical systems is the individual human being, although there is no reason to assume that other entities holding rights should be considered an a priori impossibility: if a moral agent can be offended in a way which leads to the violation of the ethical principle in question, then this agent could be able to claim a right on a par with those ascribed to individual human beings.

4

Similarly, a right implies that there be one or more duty-bearers, i.e. moral agents with an obligation to act upon the ethical demand generated by the right. But upon whom, exactly, does the duty correlated with a right fall? The focus in the discussion of universal rights is typically on the duties of the state. For several reasons, some of them historical and others pragmatic, the discussion of universal rights often focuses on the contractual relationship between a state and its citizens.

5

In contrast thereto, the focus in most discussions of ethics is typically on the duties that fall on the individual, and very little is commonly said of any duties that may attach to the state. But even the human rights conventions recognize the duty of individuals: the individual is required to assume: ”a responsibility to strive for the

3 Almond distinguishes between ”claims”, ”powers”, ”liberties” and ”immunities” as different types of demands that a rights-holder can raise. Cf. Almond, in: Singer (ed.) 2005, s.262. I will return to this in the next section.

4 Almond makes a similar point, when she concludes that the definition of which entities can be ascribed rights depends centrally on the underlying ethical principle and its premises. Cf. Almond, in: Singer (ed.),

2005, p.264.

5 The most important duty-bearers defined in the context of human rights are clearly states, which are under an: ”obligation [...] to promote universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and freedoms”.

(CCPR and CESCR, preamble) I discussed some of the background for this, as well as the implications it has for the implementation of universal rights, in section 1.4.

4

promotion and observance of the rights”.

6 (CCPR and CESCR, preamble) In general, as individuals are moral agents, they will be subject to relevant duties, i.e. rights are reciprocal.

1.2

From rights to duties

The next question in the analysis of rights is to consider the types of obligations rights imply towards the duty-bearer(s), i.e. what and how much can we demand of the moral agent who is obligated by a duty?

What, then, can rights do? One very basic way of distinguishing rights is suggested by George Rainbolt, using the twin dichotomies of active-passive and positive-negative: “Active rights are rights to do something oneself. My right to drive my truck is an active right. Passive rights are rights that another person do or not do something. Passive rights are subdivided into positive and negative rights. A positive right is a right that another person do something. A negative right is a right that another person not do something.” (Rainbolt, 2006, p.13)

However, if we apply the positive-negative distinction to active rights too, we end up with another, more celebrated typology of rights, proposed by Wesley Hohfeld and split into four classes: ”rights”, ”privileges”, ”immunities” and ”powers”.

(Almond, in: Singer (ed.), 2005, p.262; also: Rainbolt, 2006, p.11ff) A right, in

Hohfeld’s terminology, corresponds to a passive positive right, and allows the rights-holder to raise a demand which must be respected by the relevant dutybearer, e.g. the right to education, which allows the rights-holder to demand that

6 Individual obligations also feature in the UDHR, in which it is stated that: ”1. Everyone has duties to the community in which alone the free and full development of his personality is possible. 2. In the exercise of his rights and freedoms, everyone shall be subject only to such limitation as are determined by law solely for the purpose of securing due recognition and respect for the rights and freedoms of others and of meeting the just requirements of morality, public order and the general welfare in a democratic society.” (UDHR, article

29)

5

the state supply free access to such. (CESCR, article 13) Privileges correspond to active negative rights and free the rights-holder from an obligation that the individual would otherwise fall under, i.e. they function as limitations of the demands that other rights-holders can raise. An example could be the rights of the child to not be held prisoner in an institution alongside adults. (CCPR, article 10, section 2 (b) and 3) Immunities correspond to passive negative rights, and are thus rights that protect the rights-holder from the actions of other agents, e.g. the right to freedom of religion. (CCPR, article 18) Finally, powers correspond to active positive rights and grant the rights-holder the right to perform certain actions.

The right to vote and thereby grant powers to elected leaders is one of the relatively few examples of this type of right in human rights. (CCPR, article 25)

1.2.1

Negative and positive rights

For duties, the central distinction discussed above is the division between positive and negative rights.

7

A negative right generates a duty not to act so as to cause a violation of the right.

Moral agents are thus free to maintain inactivity without violating their responsibility. A common example is the right to free speech, which implies a negative duty to not prevent individuals from speaking their mind, even on controversial issues, e.g. by practicing censorship.

A positive right, in addition to the prohibition against causing a right’s violation, also generates a duty not to allow the right to be violated. Moral agents are thus

7 Indeed, the distinction between active and passive seems somewhat dubious in general, despite its intuitive appeal: if, to use Rainbolt’s example, I have the right to drive a truck, is that an active right, because it allows me to do something, or a passive right, because it prohibits others from preventing my doing it? And what, exactly, is an active right to do something supposed to be, if not a prohibition that others prevent my doing it?

6

required to actively intervene on behalf of the rights-holder, and in-activity is allowable only when the right in question is secure. A typical example of a positive right is the right to education, which not only prohibits preventing people from access to education, but also establishes a duty upon the state to create and maintain a public education system.

The intuitive appeal of a theory of negative and positive rights is its ability to combine the two features of coherence and economy. Negative rights support coherence, because if my duties with respect to a right require me only to refrain, then it is much harder to conceive of situations where my ethical duties will come into conflict with each other. Ethical conflicts arise when we are at once morally committed to performing two mutually exclusive actions. Duties to refrain will rarely lead to such dilemmas. At the same time, negative rights are economical, in the sense that it will typically require smaller personal sacrifices to fulfil the duties that result, in comparison with the duties generated by a positive right. This makes it possible, in general, to make a negative right stronger than the equivalent positive right; absolute rights are nearly always conceptualized as negative.

8

These two features make the distinction appealing, but this should not be confused with proving that the distinction exists or is ethically relevant. What they show is

8 I will return to the question of the strength of a right in section 2.5.2 below. Note also, that there may be cases where this relation between negative and positive rights does not hold true, but generally speaking

“inaction” places less of a burden on the individual than “action”. Jonathan Glover, when considering an absolute right to life, observes that interpreting it as a positive right would arguably mean that: “…we would have to give money to fight starvation up to the point where we needed it more than those we were helping: Perhaps to the point where we would die without it. For not to do so would be to allow more people to die, and this would be like murder. And, apart from this huge reduction in our standard of living, we should also have to give up our spare time, either to raising money or else to persuading the government to give more money. For, if a few pounds saves a life, not to raise that money would again be like murder.”

(Glover, 1990, p.93)

7

that there would be two specific advantages if this were in fact so, and hence that it may be worth our time to investigate if it is or not. But additional arguments will be needed to support that it is in fact the case.

1.2.2

First and second generation human rights

The question of whether rights can be divided into positive and negative may seem peripheral to the investigation of universal duties – certainly, whether a right is positive or negative does not affect whom the duty falls upon, i.e. its universality, only in what circumstances it dictates our actions. When I introduce it here, it is because one way that negligence of universal duties is commonly excused is with reference to this distinction: if rights-holders have only a negative right, then we can justifiably stand by and do nothing while people suffer. Thus, the state of misery that I described in chapter 1 (cf. section 1.4.1) is not a moral problem on this account, even if there are universal rights: the fact that millions of people are starving, poor, uneducated, sick, etc. across the world does not mean that I have failed my moral duties in any way, as long as I have not actively caused them to starve, lose their means of subsistence, access to education, or health.

9

We find this eminently exemplified in the distinction within human rights between first generation and second generation rights, which is made manifest in the way that the two UN conventions of human rights are constructed: CCPR contains first

9 Cf. Kwame Anthony Appiah, who defends his “partial cosmopolitanism” against more comprehensive consequentialist principles by objecting not to universal duties but to positive rights: “The problem with the argument isn’t that it says we have incredible obligations to foreigners; the problem is that it claims we have incredible obligations. Whatever has gone wrong, you can’t blame it on us cosmopolitans.” (Appiah, 2006, p.159f)

8

generation negative rights and CESCR second generation positive rights.

10 The first consists of the classical liberal civil and political rights, centrally the right to life and liberty, the second consists of the rights of distributive justice, including the rights to work, food and equality of opportunity. But when we review the type of duties that the two types of rights generate, it is abundantly clear that negative rights are considered to generate strong duties, while positive rights generate duties so weak as to border on benevolence: The articles of the CCPR attribute to every human being a number of immediately and indefinitely valid rights, while

CESCR, on the other hand, merely asserts the obligation to take the steps possible beyond a vaguely defined threshold to gradually realize the rights.

11

The debates on first and second generation human rights tend to focus on two issues: on the one hand on the justification for positive rights, and on the other on the priority between the two generations of rights, as their varying claims may generate moral dilemmas in some situations. (Donnelly, 2003, p.27ff) Thus, one way to argue that second generation rights are more important than the existing conventions suggest is to point out that most first generation rights have little meaning if they cannot be exercised due to economic or social pressures: “No one can fully enjoy or exercise any right that she is supposed to have if she lacks the essentials for a healthy and active life. Even if most rights are oriented towards the

10 I leave out here the discussion of third generation rights which are said to be community rights, including environmental rights and some types of cultural rights. (Ishay, 2004, p.3ff; Robertson, A.H. and Merrils,

J.G., 1996, p.274ff; Donnelly, 2003, p.27ff)

11 Thus, article 2 of CCPR reads: “Each State Party to the present Covenant undertakes to respect and to ensure to all individuals within its territory and subject to its jurisdiction the rights recognized in the present Covenant…” The same article in CESCR reads: “Each State Party to the present Covenant undertakes to take steps, individually and through international assistance and co-operation, especially economic and technical, to the maximum of its available resources, with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of the rights recognized in the present Covenant…”

9

exercise of agency and freedom, still we know that things like malnutrition and epidemic disease can debilitate and finally destroy all the human faculties that individual autonomy involves.” (Waldron, in: Goodin and Pettit (eds.), 2001, p.578f) This is a strictly instrumental argument: first generation rights are granted priority, and the legitimacy of social and economic rights follows from the fact that they are necessary to enjoy the civil and political rights. Another argument is to attack the categorization into two groups, by acknowledging that first generation rights too require a considerable effort to uphold, and that it will therefore be difficult to classify a right as being first or second generation using the cost of meeting the obligations entailed as a criterion. (Eide, in: Eide et al, 1994) But there is, I believe, reason to be sceptical of the distinction on a more fundamental level.

1.2.3

Does the negative-positive distinction hold?

I have suggested that there are reasons to be sceptical of the way the traditional distinction between negative and positive rights is framed within human rights, but even on a more general level it seems to have strongly counter-intuitive consequences – consider the right to life: “Clearly each of us can say to herself, ‘I must not kill P’. Clearly also if Q kills P, then it is incumbent on the rest of us to condemn Q and call for her apprehension and punishment. But suppose R has an opportunity to prevent Q from killing P, but that doing so will involve considerable cost to herself. Does she have a duty to prevent the killing? And, if so, is that duty as important as her own duty not to kill P?” (Waldron, in: Goodin and

Pettit (eds.), 2001, p.577f) A classic example to illustrate that a right to life, if it is to be meaningful, must entail more than the obligations that follow from negative rights concerns a drowning man. (Cf. Kagan, 1998, p.95f) His right to life is, according to the traditional model of negative rights, violated if I push him in the water and cause his death by drowning. But if all he holds is a negative right, then

10

I can calmly stand by and watch another push him, and afterwards claim that my complete lack of action in no way violated my responsibilities as a duty-bearer.

12

Similarly, if he trips and falls into the water on his own, and I merely happen to be passing by, I need not take any action (such as crying for help, or throwing him a life-belt), but can walk on or pause to enjoy the spectacle as I please. This seems absurd, and one might reasonably point out that the right to life is not much good to this poor fellow, who will wind up equally dead in all three scenarios.

It seems far more plausible to assume that if he genuinely holds a right to life, and I am under a duty with respect to that right, then I am obligated not only to refrain from pushing him in, but also to intervene in the other two scenarios. Surely, it is the perspective of the rights-holder that matters, and: “…what matters to P is simply not being killed , as opposed to not being killed by any agent in particular. If this interest is really the basis of R’s duty, R should be as concerned about the threat posed to P by Q’s actions as she would be about any threat posed to P by her own.” 13 (Waldron, in: Goodin and Pettit (eds.), 2001, p.577) There could be other circumstances that would abrogate my duty, e.g. I may not be required to risk my life by fighting a would-be murderer or by leaping into a wild and turbulent sea, but it seems incompatible with taking the rights of other people seriously to insist

12 Note that this is putting it stronger than most proponents of the division would be willing to accept. As

Kagan states, an ethical theory that maintains a division between doing harm and allowing harm can both condemn the violation of positive rights (or “allowing harm”) and maintain that the moral severity of this type of violation is substantially less than that of violating a negative right: “The deontologist’s position, then, is this: Allowing harm is certainly morally important; it’s just that doing harm is even more important.” (Kagan, 1998, p.96) I will return to whether this is plausible in section 2.3.

13 Waldron perceptively notes that this also means that rights and the attendant duties work differently than more traditional absolute deontological duties – duties can and will conflict with each other, and in these situations it will be necessary to weigh different scenarios against each other in the style familiar to consequentialism.

11

that there are no situations in which I might be required to do more than simply

“refrain”.

But apart from the strong intuitive appeal of a more encompassing duty than that entailed by negative rights, is it possible to argue against the basic dichotomy between doing and allowing, action and inaction, from a more analytical perspective? I think it is.

1.3

Assigning responsibility: causality and morality

A serious problem for the division into positive and negative rights and their corresponding duties concerns the idea that it is possible to maintain a meaningful and morally relevant distinction between doing and allowing, or action and inaction. The distinction rests on two premises: first, that it is possible to meaningfully define a concept of inaction, i.e. to distinguish between positive and negative causality. The issue of causality is notoriously tricky, but I will try to show that this is not the case. Second, that a morally significant difference between action and inaction can be shown. This premise, too, I will attempt to show has little credibility. In conclusion, I reject the distinction between positive and negative rights and duties, and thus maintain that a right generates more comprehensive duties than the concept of negative right entails.

1.3.1

Causal responsibility

The first problem for the distinction is the difficulty of defining the difference between action and inaction on a causal level. Because what, exactly, does it mean in a moral context to “not do something”? The vagueness of the action-inaction dichotomy shows in how difficult it can be to determine whether to best describe a rights violation as a failure to act or a wrongful action, i.e. as a duty obtaining towards a positive right or a negative right. Shelly Kagan uses the example of making a promise: “At first glance, this may strike us as being a positive duty: to satisfy it you must do something, keep your promises. But our intuitions shift if we

12

redescribe this very same requirement in the language of constraints. For now we have a constraint against breaking your promises, and this makes it sounds like a negative duty. So which is it? If the distinction between positive and negative duties is going to be of any significance, it had better be more than a momentary artefact of the language we happen to pick to describe our obligations.” 14 (Kagan,

1998, p.131)

Inaction seems to be something of an abstraction then. The most plausible understanding seems to me to be that it is taking an action that does not lead to the consequences constrained by the right. Respecting the right to life of an individual, then, is better understood as “taking any of a number of actions which do not lead to a situation where the rights-holder loses her life”, than it is as “not taking an action that does lead to a situation where the rights-holder loses her life”. In

Kagan’s example above, it really does not matter whether we describe it as a constraint or a positive duty – the crucial point is that we understand that making a promise commits us to performing one of those actions that will lead to the promise being kept, and that any other action is a failure.

Where does the action-inaction dichotomy go wrong? The premise of inaction presupposes, as John Harris notes, that we understand the world as being at rest, except for those trains of events that we occasionally set in motion: “But the real world of action is busy with trains of events, some we have the power to set in motion, others are already in motion (whether caused by other agents or by the brute forces of nature) and we have the power to stop them or, by operating or not operating the points, determine where they will end up and what damage they will do on the way.” (Harris, 1982, p.64) An example will illustrate: returning to our

14 Oddly, after recognizing this difficulty, rather than criticizing the distinction, which the example eminently shows is arbitrary, he attempts to show that positive duties will, at least generally speaking, be specific obligations of universal constraints.

13

much discussed drowning swimmer and the potential rescuer on the beach, it is clear that condition R (the swimmer is rescued) prevents event D (the swimmer drowns) from occurring. The drowning can only take place in so far as condition R does not obtain; hence, non-R is a necessary condition for D. Whether the agent causes D by preventing a rescue by someone else, failing to perform one herself, etc. seems causally irrelevant. Or, as John Harris puts concludes: “…we can determine outcomes by not intervening as effectively as we can by bodily movements.” 15

(Harris, 1982, p.67)

This has serious implications for the distinction between positive and negative rights, because the crucial premise was precisely the difference between action and inaction, without which there will simply be rights that constrain our actions by sanctioning some actions and prohibiting others.

1.3.2

Moral responsibility

I have shown above that one serious problem for the distinction between doing and allowing, and hence for the distinction between negative and positive rights, is that it is very difficult to establish a believable causal distinction between the two. But even supposing that we allowed that there is a distinct and definable difference in causal terms between doing and allowing, or action and inaction, the negativepositive rights dichotomy would then encounter the second problem, which concerns the difficulty of explaining the moral significance of the distinction.

15 One problem for negative causation that is commonly noted is that it seems to multiply the causes of an event to infinity. In that situation, a reasonable question is: “What licences the promotion of any one of the infinite number of causally necessary conditions to the status of a cause or the cause of anything?” (Harris,

1982, p.63) Harris’ reply is to point out that: “this is a general problem about causation and not one for negative causation alone. Chains of positive causation are indefinitely long; each link is a causally necessary condition and we must pick particular candidates from among them.” (Harris, 1982, p.63)

14

Raymond Belliotti argues against the moral relevance of the dichotomy by pointing out that the primary support for it is an intuitive, but irrelevant distinction, that:

“It is morally worse to initiate the causal chain process than it is to refrain from stopping the process once it has begun.” (Belliotti, 1982, p.87)

Additionally, this intuitive difference can be attributed to two other factors: one is that: “…most actual examples of negative duties are morally worse than violations of correlated positive duties because harming for malicious reasons is morally worse than not rendering aid for apathetic reasons”, and this general experience tricks us into perceiving a relevant difference between the two. (Belliotti, 1982, p.84) The other is that it overlooks the principle that: “…we are expected to be more aware of the direct consequences of our actions – we must foresee the possibility of harm occurring – when our actions clearly increase the probability of harm.” (Belliotti, 1982, p.88) This too influences our evaluations of situations where we either initiate or fail to stop a causal chain, but neither has anything to do with a morally significant difference between action and inaction as such.

16

In conclusion, the division between doing and allowing, or positive and negative rights, does not seem to me to rest on a morally significant difference. In combination with the problems of determining the causal difference between doing and allowing and the intuitive appeal of a comprehensive understanding of the

16 Jonathan Glover argues along similar lines and lists a total of 5 conventional sources of confusion that lend intuitive strength to the distinction: “A) Confusions between different kinds of omission. B) The fact that the doctrine is itself confused with negative utilitarianism. C) Other factors only contingently associated with the act-omission distinction. D) Other moral priorities that are themselves questionable. E)

A failure to separate the standpoint of the agent from the standpoint of the moral critic or judge.” (Glover,

1991, p.94) Common for most of them is that they identify relevant moral distinctions that in many cases coincide with the doing-allowing distinction. This coincidence, Glover argues, then misleads a superficial consideration into perceiving the distinction as pointing to a significant difference. Cf. also Kagan, 1998, p.98f.

15

duties generated by a right, I believe that the distinction between negative and positive rights must be considered untenable.

17

As I noted initially, this has important repercussions for universal duties, because it means that we can no longer dodge our responsibilities by objecting that we have not done any wrong. This makes the question of whether there is some way to justify limiting the duties that follow from universal rights all the more pressing, so let us turn to the issue of universality and explore exactly what it means for a right and a duty to be universal.

1.4

Extent - universal rights and universal duties

We turn now to the most important aspect of rights in the context of this thesis: their extent. As the crux of the problem I investigate is the situation in which universal rights can justifiably generate non-universal duties this feature of rights deserves some attention. In this section I will examine what exactly we are to understand by the term universality in the context of rights and duties, and how the connection between rights and duties with this feature work.

1.4.1

Universal rights and special rights

A universal right is a right that applies to all potential rights-holders, but there is frequently some confusion as to how to interpret this: who are all the potential rights-holders? For instance, the rights of children are said to be universal, by which it is commonly meant that they apply to children everywhere, not just

17 I believe that a better way of approaching duties, which will match some of the intuitions invoked by the distinction, is to consider the feature of thresholds (see section 2.5.2 below), and to recognize that if thresholds apply to a duty then the type of duties traditionally conceived as negative will on average be less likely to meet a threshold than those traditionally conceived as positive. This, I believe, is a plausible and coherent way of analyzing the issue, although it will need to be reviewed on a case-by-case basis as it does not allow us a principal distinction of the sort invoked by adherents of the negative-positive dichotomy.

16

children in some places. But this is not commonly meant to imply that nobody but children have rights, i.e. that they exhaust the group of all potential rights-holders for all rights. Initially, we need therefore to clarify what extent the qualifier

“universal” lends to a right.

Simon Caney suggests distinguishing between universalism of form (the right applies to everyone) and universalism of scope (the right applies everywhere).

(Caney, 2006, p.26f) The rights of children are universal in scope, then, because they apply everywhere, but not of form, because they do not apply to everyone. But while universalism of scope is an uncontroversial definition, his definition of a universalism of form seems to overlook the need to argue for his identification of human beings as the relevant group.

18 This is a usage that is fairly commonly accepted, but it is also one which, despite its intuitive appeal, encounters serious problems because the definition of human beings as “everyone” needs further justification to avoid being arbitrary. The discussion of the morality of free abortion, for example, often centres on the question of whether foetuses can legitimately be excluded from the group of rights-holders.

Nevertheless, the concrete sense of universalism which defines human beings as the group of all potential rights-holders is pervasive enough that it is this type of universalism that I deal with in this thesis. Throughout the thesis I shall assume therefore, as do the theories I subject to analysis, that the group of entities that possess the feature of being a potential rights-holder is numerically identical with the group of human beings.

18 In fairness to Caney’s approach, it should be noted that the crucial issue for him is to defend universalism against cultural relativism, and that it is in the context of this discussion that universalism of scope becomes particularly relevant, as opposed to the cultural relativist claim that morals apply only within bounded cultures.

17

To clarify then, universal rights in the formal sense are rights that apply to all rights-holders who have the feature “is a potential rights-holder”, in practice all human beings.

19 A special right, in contrast thereto, is a right that all rightsholders with feature x hold, where feature x can be e.g. “is a child”, “is a pregnant woman”, “is a disabled person”, etc.

1.4.2

Universal duties and limited duties

A universal right, then, is one that applies to all human beings, although strictly speaking it is a right that applies to all rights-holders, whatever they be. A universal duty is similarly one that applies to all moral agents, i.e. one which designates all moral agents as duty-bearers.

But it is important to keep in mind that this is different from the sense in which a universal duty is taken to mean that a duty-bearer has a duty towards everyone equally. A distinction similar to that suggested by Caney above (cf. section 2.4.1) thus applies: we need to distinguish between duties with universal extent, which apply to all duty-bearers, and duties with universal scope, which extend towards all rights-holders. Their respective opposites are duties with limited extent (duties that only extend to some duty-bearers) and duties with limited scope (duties that only extend towards some rights-holders).

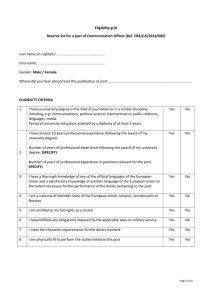

We can illustrate this with the following model, Universal rights and where R stands for rights-holders, D for dutyuniversal duties bearers and the arrows for the obligations that obtain between them. In this model then, the

R

1

D

1

R

1

R

2

D

2

R

2

R

3

D

3

R

Fig. 2: Universal duties, e.g.

3

19 Note that the trait of possessing one or more rights is not the same as being a potential rights-holder. rights, if any, such entities have.

18

total group of rights-holders have rights that generate duties upon the total group of duty-bearers towards the total group of rights-holders, i.e. universal rights and universal duties.

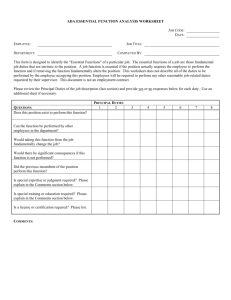

Similarly, we can illustrate the two types of limitations with the following models, in which duties have been restricted in one sense or the other.

In the first, the universal rights generate duties with a limited extent, but of universal scope, i.e.

Universal rights and duties with limited extent

R

1

D

1

R

1 duties that fall only upon a specific individual or group of individuals, but which these duty-

R

2

D

2

R

2 bearers hold towards everyone. An example could be the duties delegated by a cooperative scheme, e.g. those a life-guard would hold in our recurring scenario of the drowning man.

R

3

D

3

R

Fig. 3: Duties with universal scope and limited extent, e.g. cooperative schemes

3

In the second, the universal rights generate duties only upon a particular group of dutybearers, who then hold these duties only towards a particular group of rights-holders, i.e. the duties are limited in both extent and scope. An obvious example is the common interpretation that at least some of the duties which follow from human rights only obtain between fellow citizens.

Universal rights and duties with limited scope

R

1

R

2

D

D

1

2

R

R

1

2

R

3

D

3

R

Fig. 4: Duties with limited scope and universal extent, e.g.

UN human rights

3

19

1.4.3

From rights to duties – disanalogy properties

Rights tend to generate reciprocal duties between similar moral agents: “If P has a right against Q, then Q will usually have a similar right against P so that Q’s own duties are reciprocated by responsibilities that her right in turn imposes on P.” (Ref.

Waldron!) An essential feature of universal rights is therefore that, as all moral agents hold them, they will generate the same type of obligations towards everyone. Hence, ceteris paribus, a universal right will generate duties of both universal extent and universal scope. But this leaves the issue of limited duties unresolved: when does a universal right generate limited duties, and how do we distinguish this situation from a special right – how are we to interpret e.g. the duties of family members towards each other?

First we should note that special rights and universal rights can both apply to the same situation: a rights-holder can, for example, hold rights both as a child (special rights) and as a human being (universal rights). This is one reason why it can be hard to distinguish cases of universal rights generating limited duties from cases involving special rights.

In both cases however, the crucial feature is what Caney refers to as the disanalogy property: A morally significant difference between the agents upon which the duty falls and/or is directed towards, and those it does not/is not. (ref. Caney!) A right generates a duty with limited extent and/or scope when the right involves a special relationship between the relevant agents. Accordingly, making a promise establishes a duty with limited extent (the promise-maker(s)), which can also be of limited scope but need not.

20 In this example, the disanalogy property which

20 I could promise to give you one dollar, or I could promise to give one dollar to every single person in the world.

20

justifies limiting the scope and extent is the contractual relation between the promise-maker(s) and those towards whom the promise was made.

21

Translated into restrictions on the circumstances under which duties can be limited, it implies that any limited duty must make a disanalogy argument that:

1) is morally relevant to the right in question, and

2) justifies limiting the extent and/or scope of the duty, while also

3) avoiding that the limitation decreases either the number of duty-bearers or the targets of the duty to zero. In this case, it is not a limitation, but an abolition of the right.

22

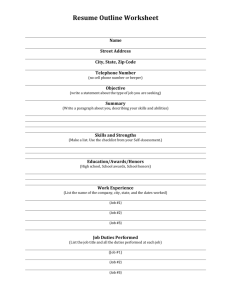

Also, note that although a universal right can generate universal duties in both senses, a special right will at most generate a duty of universal extent (i.e. carried by all duty-bearers), but with limited scope (i.e. that only applies only to the relevant rights-holder(s).) 23 We can illustrate this with the following model, in which

R1 holds a special right, which generates a

Special rights and duties with universal extent

R

1

R

2

D

D

1

2

R

R

1

2

R

3

D

3

R

3

Fig. 5: Special rights and duties with universal extent, e.g. the rights of disabled people

21 Kagan seems to support this understanding, although he is not entirely clear on the subject, when he writes that: “In effect, for a general obligation each person has the relevant obligation to every other person

– unless special circumstances have cancelled or overridden that obligation. In contrast, for the various special obligations, a given person has the relevant obligation to another given person only if special circumstances have created or generated it.” (Kagan, 1998, p.126)

22 Simon Caney develops these observations while discussing Brian Barry’s criteria for limiting the application of a general rule: “…any proposal to exempt some people from general rules must satisfy a number of stringent conditions. It must show that there is a rationale for a rule. It must then show that there is a case for exempting some from that rule. And it must also show that this case applies only to some, and not to all, people for otherwise it would call for the abolition of the rule.” (Caney, 2006, p.51)

23

21

universal duty, but only, of course, towards R1. An example could be the rights of disabled persons for special assistance and consideration. The duty might extend to everyone, i.e. be universal, but would not include people who do not have similar disabilities in its scope.

To sum up: A universal right is a right that applies to all potential rights-holders, which normally means all human beings. A universal duty is a duty that applies to all potential duty-bearers. A limited duty is a duty that is either only carried by a limited group of duty-bearers (extent) or only directed at a limited group of rightsholders (scope), because a disanalogy property exists that justifies limiting the duty.

1.5

Alienability and strength

Two other features of rights are relevant to the investigation at hand: we need to distinguish the situation where a duty is limited from the situation where a duty does not obtain because the right does not apply or has been abrogated. This concerns whether a right is alienable and the moral weight of the claim it makes, i.e. the alienability and strength of a right. While the results will be similar, in that agents will not hold active duties towards those that fall outside the domain demarcated by any of the three features, they are separate criteria.

That a right is inalienable means that it is inherently tied to the rights-holder, and that it can neither be lost nor relinquished. (Kagan, 1998, p.174) The strength of a right concerns the threshold of its fulfilment and how strong the duties it generates are. If a right has an absolute level of fulfilment, there is an individually determined point at which it is enjoyed and beyond which it does not generate duties. If a duty is absolute it has a moral prerogative, in that no other interests, moral or non-moral, can justify setting aside or violating the right. (Almond, in:

Singer, 2005, p.266) In this section, I will briefly explore these features, primarily to clarify how they differ from universality as described above. This is important, because a number of arguments that may superficially seem to deny the

22

universality of a duty will really concern the alienability and strength of the correlated right.

1.5.1

Alienability - inalienable and optional rights

Whether a right is alienable or not depends, as stated above, on whether it is inherently tied to the rights-holder or can be lost. If the right is due to a condition which is subject to change, then it will be an alienable right, so that e.g. a pregnant woman might be eligible for certain rights, which she will lose again at the termination of her pregnancy. If, on the other hand, the right is due to a condition which is not subject to change, then the right will be inalienable.

24 A logical consequence of this is that a universal right must be inalienable. If there is no group who does not hold the right, then there is no way to place an individual outside of its scope. Or to put it the opposite way: only an inalienable right can be universal, because only a right that cannot be lost will by definition apply to everyone.

25

A closely related feature is optionality, i.e. whether or not rights can be relinquished by the rights-holder. The most prominent example where optionality becomes crucial is probably the dilemma posed by a chronically ill person who wishes to relinquish the right to life in favour of euthanasia.

26 A less dramatic

24 We should note that strictly speaking even rights generally considered inalienable depend on conditions subject to change, i.e. they change with the death of the rights-holder. Remember that a precondition of a right is that it is held by a moral agent, and thus the disappearance of the moral agent from the equation will make any right invalid. A right, I believe, should therefore be properly classified as inalienable if it cannot be lost, short of the disappearance of the rights-holder.

25 A universal right need not, however, be absolute. For a right can both apply to everyone and be abrogated due to a threshold. And though a universal right must be inalienable, an inalienable right need not be universal.

26 Cf. Kagan, 1998, p.174f. Kagan emphasizes that the quality of a right being an option is non-essential, in that it is possible both to define some rights with or without options, e.g. the right to life, and to define some

23

example could be the right involved in keeping a promise: if you make a promise to me, we will typically allow me to relinquish my right to have it kept and so release you from the duty of fulfilling it. A deontological foundation such as that claimed by the UN human rights will typically lead to rights being inalienable, and so will frequently not allow rights to be relinquished, although the traditional focus on the autonomy of the person can be used to argue in some cases that consent to holding the right is a precondition for it.

To sum up: The alienability of a right concerns whether the right will apply or not.

A right is inalienable if it can neither be lost nor relinquished. A right is optional if it can be lost at the request of the rights-holder.

1.5.2

Strength – fulfilment, abrogations and prima facie duties

The feature of alienability is closely tied to that of the strength of a right, i.e. how encompassing a claim it makes and whether violating the right can ever be justified.

The difference is that, unlike a right that is alienated and therefore does not apply, a right that has been fulfilled or which can justifiably be violated still obtains. Not only could it apply in other situations, but it will also help determine the best course of action in the concrete situation.

27 rights where optionality is an integral part of the content of the right, and thus cannot really be part of its formal structure. Consider, e.g. the strangeness of making the freedom to choose between practicing religion or not practicing religion an optional right. Nonetheless, optionality is an important part of many liberal conceptions of rights.

27 Consider a criminal threatening the life of innocent civilians. We might think that a policeman would be justified in shooting and killing him, even though this violates the right to life of the criminal. Is this because his right to life is lost, e.g. because of his own violation of the social contract that granted it to him in the first place? Or is it because his actions have justified an abrogation of his right, e.g. because of losing a conflict with the rights of the innocent civilians being threatened? In the second interpretation, the best course of action will be for the policeman to peacefully subdue him, although shooting to kill will be a

24

The issue of strength also concerns when a duty is fulfilled. Unlike most forms of consequentialist ethics, rights typically define sub-optimal standards: they have a point at which they are enjoyed, and make no requirements of the duty-bearers, i.e. at which no actual duties obtain.

28 But this point can be defined either definitely or relatively. Most rights are definite: the point at which they are satisfied can be measured irrespective of the situation of other rights-holders. E.g. enjoying the right to education does not depend on others enjoying or not enjoying their right.

By contrast, a right is relative if it is fulfilled only under specific circumstances that involve the situations of other rights-holders. Many economic rights will have this form. Thus, an egalitarian principle founding e.g. a right to economic equality requires not a minimum portion of values (money, opportunities, etc.) allocated to each rights-holder, but that their respective portions be measured against each other, and that the distribution between them be equal. In fact, such a right may be satisfied even when every rights-holder is allocated a portion of values that would fail to satisfy an absolute right, e.g. a minimum subsistence right to enough values to lead a life of opportunity and dignity.

29 legitimate if less desirable alternative. In the first interpretation, neither action is more desirable than the other.

28 One could perhaps consider act-consequentialism to involve a relative right to be part of a consequenceoptimizing scheme, i.e. to hold all other individuals to acting in such a manner as to optimize the total consequences. This would be a radical version of a relative right, which is satisfied in only one instance: when everyone does in fact act in a manner that will optimize consequences.

29 Thus, as David Miller observes, e.g. economic rights may, depending on how they are framed, set the bar far lower than an egalitarian principle: “…policies aimed at securing human rights worldwide, or policies that give priority to people whose material standard of living is very low, are not in themselves egalitarian policies, although of course they can be pursued as one part of an egalitarian strategy. They are not egalitarian because their goal is not to achieve equality as such along any dimension. […] Thus if people have a right to a subsistence income, protecting that right is consistent with allowing significant inequalities of income above the subsistence level.” (Miller, 2005A, p.59)

25

The strength of a right also concerns the strength of the correlative duties. An absolute duty is a duty which cannot be set aside irrespective of circumstances.

Often, however, rights will only generate prima facie duties, i.e. duties which apply only given certain conditions. Typically, these conditions will take the shape of thresholds, which means that the question of whether the prima facie duty applies or not is resolved by weighing the “cost”, in terms of other morally relevant considerations, and determining if this cost has exceeded a predetermined point, i.e. the threshold. If the threshold has not been crossed, the prima facie duty instantiates to an actual duty, but upon crossing the threshold the right is abrogated, i.e. it no longer generates an actual duty.

30 (Rainbolt, 2006, p.18)

The most obvious types of thresholds are those that obtain in conflicts between different rights. The classic example of killing one innocent visitor to a hospital to donate his organs to and thus save five chronically ill patients illustrates this type of logic, as well as the type of reasoning that leads some to consider consequentialism an unviable approach to ethics: consequentialists will consider the threshold to have been met and the rights of the visitor to have been abrogated, whereas even moderate deontologists who recognize the existence of thresholds

30 The UN conventions supply an obvious example in their definitions of the rights that can be abrogated and the circumstances under which this can be justified, e.g. in the fourth article of the CCPR, which states that: “ in time of public emergency which threatens the life of the nation and the existence of which is officially proclaimed, the States Parties to the present Covenant may take measures derogating from their obligations under the present Covenant to the extent strictly required by the exigencies of the situation, provided that such measures are not inconsistent with their other obligations under international law and do not involve discrimination solely on the ground of race, colour, sex, language, religion or social origin.

No derogation from articles 6, 7, 8 (paragraphs I and 2), 11, 15, 16 and 18 may be made under this provision.”

26

will typically insist that the threshold has not been met, and that the killing is therefore a clear violation of the visitor’s rights. (Kagan, 1998, p.71f) 31

To sum up: The strength of a right the weight of the ethical obligations that obtain because of it – a strong right will generate strong duties. First, a right can involve a more or less expansive claim, and this claim can be either definite or relative.

Secondly, a right is absolute if the duties it generates are not subject to a threshold, and therefore cannot be set aside by other moral concerns. A prima facie duty is a duty that is subject to a threshold, and must therefore be weighed against other concerns deemed morally relevant. An abrogation is the setting aside of a right, due to its crossing a threshold.

1.6

Sub-conclusion:

In this chapter I first analysed the concept of a right and identified three constitutive parts: rights-holder, duty-bearer and content.

In addition, I introduced the distinction between negative and positive rights as one way to limit the demands that universal duties makes on moral agents. I argued first that there are reasons to be sceptical of the way it is implemented in the UN human rights, secondly that it is intuitively implausible, thirdly that it is very difficult to see how to apply the distinction on a causal level, and finally that the moral relevance of the distinction is dubious at best: the distinction must therefore be rejected. Hence, if there are universal rights then claiming that our moral duties can be limited to not “causing harm”, while turning a blind eye to the

31 Deontological principles frequently encounter severe problems as concerns conflicts between rights, for deontological foundations will tend to support each of them as equally absolute and inviolable. How then to resolve the ethical dilemmas that result? Bentham’s famous reply was to dismiss absolute natural rights as

“nonsense upon stilts”, (quoted in: Almond, in: Singer, 2005, p.266) while other scholars have attempted to introduce supplementary principles or prioritized lists of rights to resolve the issue such as the doctrine of double-effect. Cf. Glover, 1990, p.87, also Kagan, 1998, p.103.

27

violations that occur constantly as a result of circumstance and the actions of others, simply will not do.

Lastly, I have explored what it means that a right or a duty is universal, noting that a universal right will generate duties that are universal both in extent and scope, barring the introduction of a disanalogy argument that identifies a morally significant feature which justifiably limits responsibility in some way. To clarify what it means for a duty not to extend to a moral agent, I have further distinguished between a duty not extending to a moral agent on the one hand, and a duty not obtaining because the right has been abrogated and not applying because the right has been alienated on the other hand.

With the central concept of a universal duty thus properly established I can proceed to examine the different positions on the question of whether universal rights generate universal duties. In the next chapter I will sketch three such positions, focusing on the cosmopolitan position and the internationalist position, both of which accept the existence of universal rights, but the latter of which ascribes limited duties on the basis of these.

28