The Ethics of Killing

advertisement

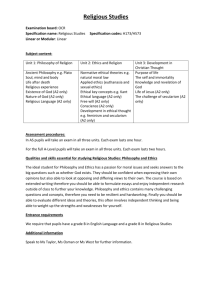

N.B. SOME IMPORTANT INFORMATION FOR CURRENT STUDENTS HAS BEEN REDACTED. A COMPLETE VERSION OF THE COURSE GUIDE IS AVAILABLE ON BLACKBOARD. UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES POLITICS THE ETHICS OF KILLING POLI 60222 Course Guide 2014/15 Semester 1 Convenors: Dr Liam Shields & Dr Steve de Wijze This is a theory course designed for those students who are specialising in the Political Theory programme of the MA degree. It is available as an option across most other MA programmes. Course Content and Rationale This course will examine 7 issues related to the ethics of killing, primarily from the perspective of non-consequentialist moral theory. Aim The aim of this course is to introduce students to some of the central questions surrounding the ethics of killing and saving. Is it permissible to kill the innocent in selfdefence? Is there a moral difference between killing and letting die? When can civilians be justifiably killed in war? Do intentions matter in deciding on the permissibility of targeting bombings? What is the moral difference between terrorism and justified military action? Is there a moral duty to avoid bringing certain people into existence, for example, severely disabled persons, or persons who will live much shorter lives than normal? Objectives On completion of this unit successful students will be able to: Understand the theoretical problems posed by the ethics of killing Critically evaluate the major arguments and positions on the topic Understand how the ethics of killing poses special problems for nonconsequentialist theories Develop their own position on the ethics of killing Course Credits The course will earn 15 credit points under the university’s credit rating system. The University’s Academic Standards Code of Practice states that a 15 credit module is expected to require a total of 150 hours of work. Prerequisites There are no prerequisites for this course *Seminar Organization* In addition to the weekly reading, each student will also be required, at the outset, to choose one topic for a brief (8-10 minutes) presentation. Presentations should aim to do two things: (1) briefly summarize the main points from one of the required readings, and (2) offer a short critical analysis or argument, i.e. the student’s own view of the reading. All presentations should be accompanied by a hand-out, and you will be required to provide a copy of the text of your presentation to me. Attendance at the seminars is compulsory. If you know in advance that circumstances beyond your control will prevent you from attending a seminar, you should email me as soon as possible to explain your absence. Assessment The assessment on this course has three parts: Essay Mark: 75% Presentation Mark: 15% Participation Mark: 10% Course Readings There is no single course book for this seminar. All readings are available either electronically, or from the John Rylands Library. Below is a list of the main journals and books that will be used – a detailed list of weekly topics and readings follows. Journals Analysis Ethics Journal of Political Philosophy Law and Philosophy Philosophy & Public Affairs The Philosophical Quarterly Ratio Books Jonathan Glover, Causing Death and Saving Lives Shelly Kagan, The Limits of Morality (available from www.oxfordscholarship.com) F.M. Kamm, Creation and Abortion (available from www.oxfordscholarship.com) F.M. Kamm, Morality, Mortality Volume I (available from www.oxfordscholarship.com) F.M. Kamm, Morality, Mortality Volume II (available from www.oxfordscholarship.com) F.M. Kamm, Intricate Ethics Hugh LaFollette (ed.), The Blackwell Guide to Ethical Theory Jeff McMahan, The Ethics of Killing (available from www.oxfordscholarship.com) Jeff McMahan, Killing in War (available from www.oxfordscholarship.com) Derek Parfit, Reasons and Persons (available from www.oxfordscholarship.com) Derek Parfit, On What Matters: Volume 1 T.M. Scanlon, What We Owe to Each Other T.M. Scanlon, Moral Dimensions: Permissibility, Meaning, Blame Judith Jarvis Thomson, Rights, Restitution, & Risk Judith Jarvis Thomson, The Realm of Rights Victor Tadros, The Ends of Harm Peter Unger, Living High and Letting Die (available from www.oxfordscholarship.com) Suzanne Uniacke, Permissible Killing: The Self-Defense Justification of Homicide P.A. Woodward (ed.), The Doctrine of Double Effect: Philosophers Debate a Controversial Moral Principle Weekly Seminar Topics Week 1: Introduction: Methods and Moral Theory Introductory lecture: No required reading but you should familiarize yourself with the thought experiments in the appendix. Week 2: Killing vs. Letting Die (or Doing Harm vs. Allowing Harm) Main Readings: 1) Judith Jarvis Thomson, ‘The Trolley Problem,’ in Rights, Restitution, and Risk, pp. 94-116. 2) Warren Quinn, ‘Actions, Intentions, and Consequences: the Doctrine of Doing and Allowing’, The Philosophical Review 98 (1989): 287-312. 3) Peter Unger, ‘Causing and Preventing Serious Harm,’ Philosophical Studies 65 (1992): 227-255. Further Readings: Peter Unger, Living High and Letting Die F.M. Kamm, Morality, Mortality Volume II, chs. 1-5 F.M. Kamm, ‘Nonconsequentialism’, in Hugh LaFollette, ed., The Blackwell Guide to Ethical Theory, pp. 208-211. Shelly Kagan, The Limits of Morality, ch. 3 Jonathan Glover, Causing Deaths and Saving Lives, ch. 7 Jeff McMahan, ‘Killing, Letting Die, and Withdrawing Aid,’ Ethics 103 (1993), pp. 250-79. Samuel Scheffler, ‘Doing and Allowing,’ Ethics 114 (2004): 215-239. Questions: Why should there be a moral difference between what we allow to happen and what we do? Does the distinction between killing and letting die depend on a further distinction between positive duties to aid and negative rights of non-interference? If we reject the distinction between killing and letting die, what implications does this have with regard to our duties to aid others? What moral rationale does Quinn provide for the killing vs. letting die distinction? Is Quinn’s argument persuasive? What should we do when our moral intuitions seem to conflict with more general principles or common sense? Is Unger persuasive in his argument that we need to beware of distorting factors when we consider hypothetical cases? How can we be sure whether it is Unger’s liberation hypothesis, or the zealotry hypothesis that provides the best explanation of our intuitions in different cases? To what extent does the past history of a situation bear on the killing vs. letting die distinction? That is, does it matter how someone has come to be in a situation where they might die, or might be killed? What implications might this have for our domestic and international political institutions? Week 3: The Doctrine of Double Effect Main Readings: 1) Warren Quinn, ‘Actions, Intentions and Consequences: The Doctrine of Double Effect,’ Philosophy & Public Affairs 18 (1989), pp. 334-51. 2) Philippa Foot, ‘The Problem of Abortion and the Doctrine of Double Effect,’ in her Virtues and Vices, (available from www.oxfordscholarship.com) Further Readings: Nancy Davis, ‘The Doctrine of Double Effect: Problems of Interpretation,’ Pacific Philosophical Quarterly 65 (1984): 107-123. F.M. Kamm, Morality, Mortality: Volume II, chs. 6, 7 F.M. Kamm, ‘Nonconsequentialism’, in Hugh LaFollette, ed., The Blackwell Guide to Ethical Theory, pp. 211-213. F.M. Kamm, Intricate Ethics, chs. 4, 5 T.M. Scanlon, Moral Dimensions, especially ch. 1 John Martin Fischer, Mark Ravizza, and David Copp, ‘Quinn on Double Effect: The Problem of Closeness,’ Ethics 103 (1993): 707-725. Shelly Kagan, The Limits of Morality, ch. 4 Jonathan Glover, Causing Deaths and Saving Lives, ch. 6 P.A. Woodward (ed.), The Doctrine of Double Effect: Philosophers Debate a Controversial Moral Principle Suzanne Uniacke, Permissible Killing: The Self-Defense Justification of Homicide, ch. 4 Questions: Is there any clear way of distinguishing those things that I intend from those things I merely foresee? Is the doctrine of double effect a faithful attempt to capture (at least part of) Kant’s principle that we must never use people as mere means? Some philosophers argue that if your death is causally related to the outcome I intend, then I also intend your death. But how close a causal relation is required? Is the problem of ‘closeness’ an insurmountable one for defenders of the doctrine of double effect? Is there any clear way of determining when a foreseeable but unintended cost of an action is proportionate to the benefit the action is intended to bring? The doctrine of double effect is a key part of just war theory. Should it play such a central role in our moral evaluation of war? Does the doctrine provide at least part of the justification for the view that there is a moral difference between terrorism and targeted bombing campaigns that have foreseeable but unintended civilian casualties? Week 4: Do Intentions Matter for Permissibility? Main Readings: 1) T.M. Scanlon, Moral Dimensions, pp. 8-36, (available from library at: http://eml.manchester.ac.uk/lib/POLI60221/POLI60221_8101.pdf and footnotes http://eml.manchester.ac.uk/lib/POLI60221/POLI60221_8102.pdf) 2) Jeff McMahan, ‘Intention, Permissibility, Terrorism, and War,’ Philosophical Perspectives 23 (2009): 345-72. (available online at: http://www.fas.rutgers.edu/cms/phil/dmdocuments/IPTW%20proof-1.pdf). Further Readings: T.M. Scanlon, Moral Dimensions, pp. 47-52 F.M. Kamm, “Terrorism and Intending Evil,” Philosophy & Public Affairs 36 (2008): 157-86. Shelly Kagan, The Limits of Morality, ch. 4 Derek Parfit, On What Matters: Volume I, chapter 7 Victor Tadros, The Ends of Harm, chapter 7 Judith Jarvis Thomson, ‘Physician Assisted Suicide: Two Moral Arguments,’ Ethics 109 (1999): 495-518. Judith Jarvis Thomson, The Realm of Rights, chapter 9 Ralph Wedgewood, ‘Scanlon on Double Effect,’ Philosophy and Phenomenological Research (2011): 464-472. Questions: What is it about intentions that appears to be so important in deciding whether or not an action is permissible? What, if anything, is the difference between a person’s intentions and a person’s motivations? Is there a way to retain some of our most strongly held moral convictions (e.g. regarding the wrongness of deliberately targeting innocent civilians in war) without recourse to the view that intentions are relevant to permissibility? What does it mean for an action to be permissible? Why does it matter that we settle the question of whether intentions are relevant to moral permissibility? What is at stake in thinking about this question? Can a person act wrongly even when she could not possibly know that her actions will result in harm to an innocent person? Week 5: Liability to Defensive Killing Main Readings: 1) Jeff McMahan, ‘The Basis of Moral Liability to Defensive Killing,’ Philosophical Issues 15 (2005): 386-405. (available online here: http://www.fas.rutgers.edu/cms/phil/dmdocuments/Basis_of_Moral_Liability_ to_Defensive_Killing.pdf) 2) Seth Lazar, ‘Responsibility, Risk, and Killing in Self-Defense,’ Ethics 119 (2009): 699-728. 3) Jonathan Quong, ‘Liability to Defensive Harm’ Philosophy & Public Affairs, 40 (2012): 45–77 Further Readings: Jeff McMahan, Killing in War, chapter 4 Jeff McMahan, ‘Who is Morally Liable to be Killed in War,’ Analysis 71 (2011). Seth Lazar, ‘The Responsibility Dilemma for Killing in War: A Review Essay,’ Philosophy & Public Affairs 38 (2010): 180-213. Kimberley Kessler Ferzan, ‘Justifying Self-Defense,’ Law and Philosophy 24 (2005): 711-49. Helen Frowe, ‘A Practical Account of Self-Defense,’ Law and Philosophy (2010): 245-72. Cecile Fabre, ‘Guns, Food, and Liability to Attack in War,’ Ethics 120 (2009): 36-63. Victor Tadros, The Ends of Harm, chapters 10-11 Firth, Joanna Mary, and Jonathan Quong, ‘Necessity, Moral Liability, and Defensive Harm’ Law and Philosophy (2012): 1-29. Questions: What does it mean for a person to be liable to defensive harm? Why do we need a theory of liability to defensive harm? What practical implications does this have? What does it mean for a person to be morally responsible (in McMahan’s sense) for imposing harm on others? Why should we believe this is the correct basis for liability to defensive harm? What does Lazar see as the central difficulty for McMahan’s approach? What other bases (apart from moral responsibility) might be plausible candidates for a theory of liability to defensive harm? Week 6: Killing the Innocent in Self-Defence Main Readings: 1) Judith Jarvis Thomson, ‘A Defense of Abortion,’ Philosophy & Public Affairs, 1 (1971): 47-66. 2) Judith Jarvis Thomson, ‘Self-Defense,’ Philosophy & Public Affairs, 20 (1991): 283310. 3) Michael Otsuka ‘Killing the Innocent in Self-Defense,’ Philosophy & Public Affairs, 23 (1994): 74-94. Further Readings: Jonathan Quong, ‘Killing in Self-Defense,’ Ethics 119 (2009): 507-537. Judith Jarvis Thompson, ‘Self-Defense and Rights,’ in Rights, Restitution, and Risk, pp. 3348. F.M. Kamm, Creation and Abortion, pp. 45-50 Nancy Davis, ‘Abortion and Self-Defense’, Philosophy & Public Affairs, 13 (1984): 175-207. Jeff McMahan, ‘Self-Defense and the Problem of the Innocent Attacker,’ Ethics 104, (1994): 252-290. Jeff McMahan, The Ethics of Killing, pp. 398-411 Jeff McMahan, Killing in War, chapter 4 Jonathan Glover, Causing Deaths and Saving Lives, ch. 10 Suzanne Uniacke, Permissible Killing: The Self-Defense Justification of Homicide Questions: What is Thompson’s violinist example meant to show us about the nature of moral rights? If I have a duty to be a Good Samaritan what does this imply? Does it, for example, imply that you have certain rights against me? What are the implications of Thompson’s abortion arguments in an age when foetuses might be safely removed from the womb in the later stages of pregnancy? If Thompson is right, and we can sometimes permissibly kill innocent people in selfdefense, what does this imply for a theory of rights? How can someone have a right not to be murdered, and yet be permissibly killed in certain circumstances? Is this position coherent? Is Otsuka’s claim that innocent threats are morally equivalent to innocent bystanders persuasive? If this claim of Otsuka’s is persuasive, does this mean he is right, and we cannot permissibly kill innocent threats even to save our own life? What implications might Otsuka’s conclusion have for just war theory? Week 7: Saving the Greater Number Main Readings: 1) John Taurek, ‘Should the Numbers Count?,’ Philosophy & Public Affairs 6 (1977): 293-316. 2) F.M. Kamm, ‘Nonconsequentialism,’ in Hugh LaFollette, ed., The Blackwell Guide to Ethical Theory, pp. 219-25. 3) T.M. Scanlon, What We Owe to Each Other, pp. 229-241 4) Michael Otsuka, ‘Saving Lives, Moral Theory, and the Claims of Individuals,’ Philosophy & Public Affairs 34 (2006): 109-135. Further Readings: T.M. Scanlon, What We Owe to Each Other, ch. 5 T.M. Scanlon, ‘Replies,’ Ratio 16 (2003): pp. 430-34. F.M. Kamm, Morality, Mortality: Volume I, chs. 5, 6 Derek Parfit, ‘Innumerate Ethics,’ Philosophy & Public Affairs 7 (1978): 285-301. Derek Parfit, ‘Justifiability to Each Person,’ Ratio 16 (2003): 368-90. Michael Otsuka, ‘Scanlon and the Claims of the Many Versus the One,’ Analysis, 60 (2000): 288-93 Michael Otsuka, ‘Skepticism about Saving the Greater Number,’ Philosophy & Public Affairs 32 (2004): 413-26. Rahul Kumar, ‘Contractualism on Saving the Many,’ Analysis 61 (2001): 165-70. Questions: Why is the issue of ‘saving the greater number’ of such interest to deontological philosophers? Instead of saving the greater number, why isn’t it permissible to simply give each person the greatest equal chance of being saved. Can this conclusion be coherently defended? Kamm and Scanlon each offer a version of a ‘balancing argument’ to explain why we must save the greater number. Is this argument plausible? Are Otsuka’s reasons for rejecting the balancing argument sound? Does contractualism offer a promising way of thinking about problems of saving from harm and the ethics of killing? Does the problem of saving the greater number show that deontological theories are incapable of coming up with convincing explanations of our moral intuitions where aggregation is concerned? If so, is this a decisive reason to favour some form of consequentialism? At the end of his article Otsuka draws some wider philosophical conclusions regarding the viability of consequentialism and contractualism. Are these conclusions only of theoretical interest, or might they have any practical consequences for political theory? Week 8: The Non-Identity Problem Main Readings: 1) Derek Parfit, Reasons and Persons, ch. 16 (available from www.oxfordscholarship.com) 2) Gregory Kavka, ‘The Paradox of Future Individuals,’ Philosophy & Public Affairs 11 (1982): 93-112. 3) Elizabeth Harman, ‘Can We Harm and Benefit in Creating?’ Philosophical Perspectives 18 (2004): 89-113. Further Readings: Elizabeth Harman, ‘Creation Ethics: The Moral Status of Early Fetuses and the Ethics of Abortion,’ Philosophy & Public Affairs 28 (1999): 310–324. James Woodward, ‘The Non-Identity Problem,’ Ethics 96 (1986): 804-831. David Wasserman, ‘The Non-Identity Problem, Disability, and the Role Morality of Prospective Parents,’ Ethics 116 (2005): 132-152. Matthew Hanser, ‘Harming Future People,’ Philosophy & Public Affairs 19 (1990): 47-70. F.M. Kamm, Morality, Mortality: Volume I, ch. 2 Jonathan Glover, Causing Deaths and Saving Lives, ch. 4 Jeffrey Reiman, ‘Being Fair to Future People: The Non-Identity Problem in the Original Position,’ Philosophy & Public Affairs 35 (2007), 69-92. Questions: (a) It seems wrong to bring a child into the world who will suffer significantly when you could choose to have a child at a different time who will be much happier. (b) But most people, even people who suffer significantly, don’t regret their own existence – they are usually glad to have been born. And so it cannot be wrong to have brought them into existence since they are glad you did so. (a) and (b) seem to deliver conflicting conclusions about the ethics of procreation. Is there a way of reconciling these two views? Does the non-identity problem show that, to make sense of (a), we must resort to some form of consequentialism that tells us to maximize happiness and minimize suffering? What is the appropriate way to define “harm”? Is it true that no individual can be harmed when we bring someone into existence? Or is Harman right that we can harm and benefit in creating? What practical implications does the non-identity problem have? For example, what does it imply about choosing (or not choosing) to have disabled children?