The Cost of Tears- Gender Related Interests in the Negligence

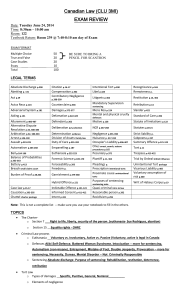

advertisement