Pangasinan An Ethnocultural Mapping

advertisement

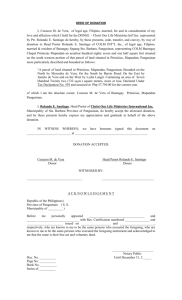

PANGASINAN: AN ETHNOCULTURAL MAPPING -marot nelmida-floresHistory and Culture always take a back seat in this age of global network and cyber transactions or what most young scholars describe as a postmodern world. Understandably, the focus is always on the global market and the pursuit of international status and recognition. The locale and the national are suddenly rendered imagined cultures and spaces, its historical and cultural import as romantic constructions of the elite. But basic education still has its responsibility to inform young Filipinos about their ethnic origins, language, history and culture. The subject of identity and ethnicity is still paramount in the interest of humanity in search of knowledge and homeland. Histories and cultures are not only constructed by the elite for language in itself has different forms of expression and articulation not exclusive to the written language of the elite. This morning, I will present to you an ethnocultural mapping of Pangasinan. What is ethnocultural mapping? It is an alternative form of mapping which focuses and privileges culture and lifeways as a response to the rigid mathematical orientation of the cartographic tradition of mapping in earlier centuries. Even geography these days as a discipline is no longer confined with physical mapping but has already embraced the idea of cultural or mental spaces with its cultural geography as a subdisicpline. The radical trend has been borne out as a result of the rigidity of scientific inquiry relating to space. In short, ethnocultural mapping does not deal alone in terms of leagues as in earlier days or modern-day geographic measurements. While calculations and measurements are still instructive in ethnocultural mapping, its foremost objective is to interrogate the construction of mental pictures of a certain place/space/region/locale in terms of its culture and lifeways. I will attempt to cover quite a comprehensive array of topics this morning but because of the usual lack of material time when it comes to presentations, I will make use of visual images with a summary of each topic’s historical and cultural import for brevity. The major topics to be covered are the following: 1. Prehispanic relations between the people of the coast (Panag-asinan or where salt is made) and the people from the Interior (Caboloan or where bolo, a specie of bamboo abounds); the political mapping made by the early Agustinian friars who named the entire region as ‘Pangasinan’ and obscured the precolonial coast-interior dichotomy of Panag-asinan and Caboloan; 2. The controversial Kingdom of Tawalisi and Princess Urduja as ilustrado/anacbanua response against Eurocentrism; 3. The Virgin of Manaoag and the manag-anito/babaylan tradition of Pangasinan; and, 4. The Cattle Caravans of Ancient Caboloan as a feudal gypsy cart in the metropolis amidst globalization. ( I will also flash some institutional landmarks, archetypes and icons in the context of modern-day Pangasinan to situate the province amidst the race towards urbanization, cosmopolitanism and globalization. <in the powerpoint>) What is the first thing that comes to mind to outsiders when ‘Pangasinan’ is mentioned? The 3 Bs – namely, bangus, bocayo, bagoong? Or for pilgrims, the miraculous image of the Our Lady of Manaoag? Or for foreign tourists, either they go see the famous 100 islands in Alaminos or seek the help of the many faithhealers that we have from almost every town or municipality to cure their ailments? PANGASINAN is all of these and more. But let us not allow only the outsiders to define our sense of identity. Let us not even tolerate Manilacentric negative views about us to predominate and hence emasculate our strong aspirations through state policies that seek only to undermine our selfhood and social location. But how can we let Pangasinan people talk about themselves presupposing we know what we want and where we’re heading when we don’t even know our past, who we are or what we’ve become? Panag-asinan-Caboloan (the coast-interior prehispanic settlements) The word Pangasinan is not an ethnic name. It is rather toponymic. According to Amurrio (1970; p. 257), Pangasinenses may have had an ethnic name but was perhaps lost through the centuries. As a toponymic term, Pangasinan means ‘land of salt’ (panag-asinan/pinagaasinan) from the root word asin with the prefix ‘pang’ and suffix ‘–an’, denoting place. In the Iluko creation myth Angalo ken Aran, the place has been cited as the land of ‘Thalam-asin’. While salt is also found in the Ilocos Region and in Manila Bay, salt coming from Dasol and Bolinao are superior in quality. And because of salt, Pangasinan is able to produce the best bagoong from the monamon fish that abound along the coast. The town of Bolinao got its name from this fish. In Tagalog, Visayan and in Bicol, ‘bolinao’ means ‘monamon’. Lingayen is popular for its own variety of bagoong which is brandnamed maniboc. But there is another name that refers to the interior plains of the province, which is not widely known. This place is called Luyag na Caboloan or ‘Place of Caboloan’. Caboloan is from the root word ‘bolo’ (a specie of bamboo) with the prefix ‘ca’ and suffix ‘–an’, meaning place. Caboloan is a place where ‘bolo’ is largely found. In earlier times, settlements which abound in ‘bolo’ include Mangatarem, Binalatongan (San Carlos), Gabon (Calasiao), Mangaldan, Manaoag, Mapandan, Malasiqui, Bayambang, Tolong (Sta. Barbara), Gerona, Camiling, Paniqui and Moncada. Even some parts of La Union province rich in ‘bolo’ were once upon a time within the Luyag na Caboloan matrix, making these towns later under the political jurisdiction of Pangasinan. This explains the thriving bamboo-based industry in the area supported by NACIDA. With the commercial production of bamboo and rattan merchandise, the cattle caravans surfaced as the mercantile outlet for these goods. (We will dwell on the cattle caravans later.) Another toponymic name, Caboloan first appeared in a grammar book written by Fr. Mariano Pellicer in 1840, entitled, Arte de la Lengua Pangasinana o Caboloan. As Vicar Provincial of Pangasinan and cura parroco of Lingayen, Fr. Pellicer knew the existence of an earlier work on Pangasinan grammar done in 1690 but was no longer in circulation in his time. Based on this earlier work, Fr. Pellicer wrote his own book. In Retaña’s Biblioteca Idiomatica Oriental (1906), Pangasinan was synonymous to Caboloan. The use of Caboloan remained until about the 19th century. The entire region was then known generally as Pangasinan when Spanish forces adopted the name of the coastal villages which they first occupied, to refer to the whole place (Cortes; 1974, pp. 1-2). Thus in pre-hispanic times, Pangasinan referred only to the coastal areas while Caboloan to the inland plains . Today, the political formation of Pangasinan is bounded on the west by the province of Zambales, on the north by Lingayen Gulf, the northeast by La Union province, on the east by Nueva Ecija, and on the south by the provinces of Tarlac and Pampanga. From the time of the conquest of Santiago Island in Bolinao by Juan de Salcedo’s men in May 1572, historians and scholars placed Zambales and La Union and some parts of Tarlac under Pangasinan. Interestingly however, in a letter dated 9 December 1572, the account of the tributes collected by Martin de Goiti listed Bolinao as another province separate from Pangasinan (The Philippines Under Spain, Book III; 1991, p.17). Sometime in the middle of the 18th century, the province of Zambales was created. La Union became a province in 1850 and towns which were previously under Pangasinan such as Rosario, Sto. Tomas, Agoo, Aringay, Caba, San Fernando, and Bacnotan were now considered to belong to the new created province. The creation of Tarlac as a province in 1875 removed the towns of Gerona, Paniqui, Camiling and Moncada from the territorial jurisdiction of Pangasinan. A number of municipalities were reterritorialized while new ones were created under the American Government (Cortes; 1990, p.5). In 1903, the western towns of Bolinao, Anda, Alaminos, Bani, Agno, Burgos, Mabini, Dasol, and Infanta which were part of the province of Zambales from mid-18th century, were turned over to Pangasinan for lack of funds and administrative problems (PF-NGOs; 1st ed., 1995). These towns were classified previously as Zambal because residents in these areas, particularly Bolinao and Anda speak the Sambal language. It is only after these were reclassified as Pangasinan towns when residents of Bolinao called their language distinctively, Bolinao. Another reason why these were under Zambales before 1903, is because they could not be reached from the capital of Lingayen on foot. The rolling formation of these towns from the Zambales ranges and the thick forests prevented commercial interaction between the residents of these areas and the coastal towns from Sual to San Fabian and the interior towns from Aguilar to Malasiqui and Mapandan. Bolinao can only be reached through the coastal waters with the use of native boats such as baloto, lanson, viray, lampitaw and ponting (Bolinao Town Fiesta Souvenir Program; 1998). This isolation made Sual the westernmost town in Pangasinan. The topographic factor also explains why these western towns lagged behind the central plains in terms of progress and urbanization. Sual only became significant when in 1855, a port was established as a result of the opening of the Philippines to international trade by the British in 1834. In fact, Sual’s ancient port area boasts of more berths than Subic’s according to some observers. The provincial government has been more concerned with the industries and investment potentials in the densely populated central plains and the coastal towns of Lingayen Gulf than in these sleepy western towns. Because the central towns are more populous, voters in these areas are prioritized in the allotment of election campaign funds. State concern over the material life of the central plains is best concretized with the construction of the dike (1935) and continuous fortification of it to prevent the Agno river from inundating the agricultural municipalities from the city of San Carlos to Tayug and particularly, the commercial districts of Dagupan, Lingayen, Binmaley and Mangaldan. After World War II, Pangasinan had been divided into three geographic units: western, central, and eastern. Recent geopolitical subdivisions of the province created six congressional districts. In the 1999 unpublished dissertation of Prospero de Vera III, he said that contemporary Pangasinan is the 3rd most populated province in the country with an average household size of 5.24 individuals per family and is classified as a 1st class province in Luzon. He noted that recent political climate favored eastern section of the province in terms of infrastructure projects such as the San Roque dam, Asingan-Sta. Maria bridge, and the San Nicolas-Sta. Fe, Umingan-San Jose road networks. While sleepy western towns were less developed than the hegemonic central plains because of their historical isolation, eastern municipalities were able to recuperate from being underdeveloped because of their road connection to northern Baguio and southern Manila. As trade routes, eastern section cannot be inevitably ignored by progress and urbanization. Coastal Dagupan was part of the original Panag-asinan. In post-World War 2 however, Dagupan’s saltbeds have been converted into fishponds. Dagupan’s famed bangus was born. How did this happen? The great flood of 1935 which inundated the agricultural fields in the central plains which also swept away the Colegio de San Alberto Magno in Calmay necessitated the construction of the dike which diverted the major flow of the Agno river from Dagupan, Binmaley, Calasiao and San Carlos to western areas such as Labrador and Sual. With the construction of the dike, the natural landscape has been altered and what used to be once the whiplashing Agno river delta (DagupanBinmaley-Lingayen) are now tributaries of the Agno, if not ubiquitous fishponds of Binmaley up to Dagupan. Calmay district however remains as the confluence of 2 major river systems: Agno and the Bued-Angalacan. This explains not only the vulnerability of the Colegio de San Alberto against floods but the brackish water that farms the delicious Dagupan bangus almost to perfection. With freshwater that is low in salinity, Dagupan is no longer a place suitable for saltmaking,but for bangus farming. And because this has become a more lucrative business than saltmaking, Dagupan is slowly ceasing to be a place for panag-aasinan but rather panag-babangusan. To date, Dagupan city is part of the congressional district of again but now embattled House Speaker Jose de Venecia. It also forms part of the so-called CAMADA (Calasiao, Mangaldan, Dagupan) or those comprising district 4, considered to be the hub of rapid urban growth. According to the 1995 Mid-Decade Goals Reports for Provinces, Cities and Municipalities prepared by UNICEF, Dagupan city has successfully met all its targets for child welfare such as education, nutrition and sanitation, health (i.e. full immunization for children and women) except for salt iodization. A big irony for a saltrich province. Dagupan’s rapid urbanization has caused some environmental problems though such as lack of housing, potable water, waste disposal and traffic. These sociological headaches are also being felt by peripheral communities as far as Villasis and the newly citified Urdaneta. Princess Urduja and the Kingdom of Tawalisi It actually all started with the debate on the location of the Kingdom of Tawalisi in the 19th century. No less than our national hero Jose Rizal constructed his own theory about the exact location of the Kingdom of Tawalisi contained in his letter to Dr. A.B. Meyer of Dresden, Germany. Rizal’s hypothesis was contained in the eminent historian Austin Craig’s pamphlet entitled, “The Particulars of the Philippines Pre-Spanish Past,” which came out in 1916. To sum up Rizal’s theory, the Kingdom of Tawalisi exists and so was the voyage of the 14th century Arab traveller Ibn Batuta who visited it. The location of the Kingdom is somewhere in the “neighborhood of the northern part of the Philippines.” With Austin Craig corroborating Rizal’s theory, Kingdom of Tawalisi and the amazon Princess Urduja mentioned in the narrative of Ibn Batuta became historical truths during the American Period. In 1925, the book Stories of Great Filipinos published by Benitez & Benitez stated the existence of Princess Urduja and her Kingdom. The biographical sketch read: About six hundred years ago, Pangasinan was an important kingdom. At one time, the ruler of the kingdom was woman whose name was Princess Urduja. (Zafra 153; 1977) Ten years after in 1935, another book published by Zoilo M. Galang, the Encyclopedia of the Philippines reiterated and expanded the entry on Princess Urduja as an historical figure. It read: When Pangasinan was a kingdom, about seven hundred years ago, there lived a Famous woman ruler in that dominion. Young, beautiful and well-educated. Princess Urduja was reputed to be a good warrior who personally led her Soldiers to the battle fields. (153) In the same year, Galang also published Gregorio R. Zaide’s book The Philippines Since Pre-Spanish which described Urduja in this way: Quite a number of famous women had appeared, like shooting meteors, across the firmament of Philippine history. Among them… was Princess Urduja, said to be the Amazonic ruler --- warrior of ancient Pangasinan, who was visited in 1349 or 1348 by Ibn Batuta, Mohameddan traveller from Morocco. All these publications legitimized the narrative of Ibn Batuta about his visit to the Kingdom of Tawalisi where he met the amazon ruler Princess Urduja. To all these however stood Dr. Nicolas Zafra of UP’s Department of History refuting Rizal’s and Craig’s opinion on the exact location of the Kingdom of Tawalisi and regarded Urduja and her Kingdom as myths. But about this time in the 20th century, the focus was no longer on the exact location of the Kingdom of Tawalisi but on the beautiful, educated, fierce amazon warrior Princess Urduja. The image of a maiden warrior has captured the imagination not only of the people of Pangasinan but of the entire nation. As a cultural icon, the exoticized image of Princess Urduja will be reproduced in paintings, movies (Amalia Fuentes original and the Susan Henson version) and other forms of art. The residence of the provincial governor is named Urduja house. Nearby here still stands the big billboard Urduja hotel in Urdaneta. Interestingly, there is still the Farmacia Urduja in Dagupan, the Rural Bank of Urduja in Tayug and the Urduja Communications building in Sual. Or even the Urduja sari-sari store in Sta. Barbara. Urduja was even adopted as symbol of the Women Development Foundation in Pangasinan and so are national feminist groups in Manila including Gabriela and Samakana. I even have a first cousin named Urduja from San Carlos married to a Braganza of Alaminos. But what is the importance of Princess Urduja and her Kingdom of Tawalisi in this day and age? As a symbol, Princess Urduja is the articulation of women (not only in Pangasinan but women throughout the country) of a romanticized glorified matriarchal amazonic past. This articulation stems from the reality of gender inequality which from a feminist perspective is a given under a patriarchal system of relations. But Princess Urduja as a symbol goes beyond feminism for her story has been believed, constructed, reproduced even by men. The historical narrative of Ibn Batuta has been eclipsed by literary stories about this exoticized maiden warrior with a colorful tapestry of a kingdom that explicitly displays its power and wealth. The myth of kingdoms and princesses are actually defensive responses to the onslaught of Hispanization. Anacbanua writer/scholars like Catalino Catanaoan and Antonio del Castillo in the 20th century reinforce the belief in a kingdom of colonial elites under Spain like Rizal who perhaps, romanticized a glorious Philippine pre-hispanic past as a reaction to Eurocentrism. In short, the significance of Princess Urduja and her Kingdom of Tawalisi does not depend anymore on whether these are historical truths or just myths because as symbol and discourse, Princess Urduja and her Kingdom underscore the powerful truth about our colonization and the reality of patriarchal relations. The Nuestra Seňora de Manaoag and Pangasinan’s Manag-Anito Tradition The province of Pangasinan has always been known for its Nuestra Seňora de Manaoag. It is also famous for its many healers, whether locally known as managtambal or nationally and internationally recognized as faithhealers. The province is often described as very religious and conservative, producing a significant number of priests and seminarians annually. Lately, with the awareness on local tourism, the political administration takes pride in the Virgin’s Well and the much talked about Pyramid of Asia. All these situated in the town of Manaoag. With the replication of the Image of the Our Lady of Manaoag throughout the country, this popular devotion through the aid of both print and visual communication has reached wider audiences, unprecedented since its first canonical celebration in 1926. But what appears to be simply a Catholic devotion to the Blessed Virgin who performs miracles, is a rich text that echoes the traditions of an ancient past, the conundrum of a colonial religious icon, and the appropriation of a people in their quest for peace and freedom. The original 17th century Spanish Nuestra Seňora to 20th century Our Lady of Manaoag, is indeed a religious symbol. Its symbology is culled from centuries of cultural encounters within a colonial setting. The ivory image brought to our shores through the missionary zeal of Fr. Juan de San Jacinto, O.P. glamorized the ancient concept of po-on, but on the other hand, personalized a stoic icon on the retablo. Precolonial ‘Tipan ng Mahal na Ina’ has her spirit descend upon a material representation in the Nuestra Seňora yet her loving and maternal care never wavered for those who truly believe in Her. The ‘Ina’ in the Blessed Virgin Mother and the Sagrada Familia are indeed closely linked to the Filipino family. The Nuestra Seňora de Manaoag as the ‘Ina’ and ‘Apo Baket’ among Pangasinan and Iluko folk is the effervescence of hope and love. She is the perpetual ‘Ina’ especially of the poor and needy. Appearing on a hill, the narrative of apparition renews earlier notions of sacred places, however, negotiated upon by the construction of a church, thus expanding the scope of the ‘sacred’ and the ‘holy’ from the natural landscape to the imposing fachada of the Shrine. This historia de la aparicion observed to flourish in medieval narratology and said to contain primordial appeal is less of a universalist Catholic phenomenon than an articulation of humanity that is perpetually in bondage. The two versions of the Nuestra Seňora’s beginnings reflect the polarized worldview and predisposition of the church and the folk. The official version was inspired by the evangelical obligation to protect and promote early Christian settlements while the folk version was compelled by historical circumstances of Christianization. Yet, the folk version with its emphasis on the historia de la aparicion is intoned, reproduced and propagated even by the church for its popular and perhaps, primordial appeal. With this seeming approbation of the church, the folk version, thus contain both the ecclesiastical discourse on Christianization and the folk discourse on appropriation. Like in the icon of the Nuestra Seňora, its narrative proved to be another important site of negotiations between Judeo-Christianity and the Manag-anito tradition, a powerful cultural interface between Spain and the Philippines. This inevitable church’s approbation of folk appropriation of the Nuestra Seňora is best captured through the fiducial character of the Blessed Virgin’s canonical celebrations. The indescribable jubilation among the faithful approximating the wild and the exotic especially during the actual coronation of the Blessed Virgin outside of church’s premises, can either be understood as the unleashing of suppressed energies or reminiscent of ancient manag-anito’s ritual practices. Academic lens look at it as a study on ethnology where behavior of native converts shift from the somber to the chaotic once a religious image is taken out of the church. For lo and behold, the image becomes a possession of the multitude rather than a property of the church. But the most significant consequence of the iconography and narrativity of the Nuestra Seňora is the revitalization of the manag-anito’s healing tradition through the Nuestra Seňora as the main source of potency and spiritual powers. This did not only preserve the performance of healing rituals but even spawned religious movements, monuments and healing ministries. From the Guardia de Honor de Maria and its antecedent Los Agraviados, to the Crusaders of the Divine Church of Christ and to Sister Adela Healing Ministry, the history of Pangasinan’s religious tradition has never been inadequate and unexciting. The Cattle Caravans of Ancient Caboloan Caravan cultures throughout the world depict stories of real journeys, discoveries and exploits. They also account for the construction of local histories, territories and market societies. At best, caravan routes map the geoeconomic and the ethnohistoric trail of peoples on the road towards venture capitalism in the earlier centuries. But in the 21st century, the history of caravan cultures remain only in the people’s memory as artefact (or artifice?) and which has been romanticized into bioepics or heroic adventures of legendary men caught in the age of material adventurism from the 13th to 16th centuries. In this day of global network and cyber transactions, it is fascinating and at the same time remarkable how the caravan culture still persists in the Philippines. Its persistence as a vestige of feudal past in an era of intensified commercialization and industrialization is indeed indicative of uneven modes of development, as it is symbolic of intersecting diverse cultures where the rural locale ventures into the national and into the global with far reaching implications on issues of ethnicity and cultural import. The cattle caravans of ancient Caboloan continue to peddle their bamboo-based products from the province of Pangasinan to the highways of Metro Manila. These are the ubiquitous cattle-drawn carriages selling hammocks, bamboo chairs and bookshelves we see in front of SM Fairview, Commonwealth, East and C.P. Garcia Avenues. But not until recently when Metro Manila Development Authority (MMDA) agents found them illegally parked along national roads thereby considered obstruction to traffic. More than just a cultural icon for tourists, the cattle caravans trace its origins to the ancient Caboloan, an interior ethnic state in the province of Pangasinan. Caboloan refers to a place where ‘bolo’ (a specie of bamboo) is abundant which explains why the cattle caravans up to this day peddle goods made from bamboo and rattan. These bamboo-based products are traded in prehispanic times with the coastal villages known then as ‘Panag-asinan’ or where salt was produced. This interior(alog)-coast (baybay) dichotomy and its accompanying trading relations was obscured by the colonial mapping of Spanish Augustinian missionaries, who coming from the coastal town of Bolinao named the entire region as Pangasinan. This prehispanic cultural relations between the interior-coast dichotomy of Caboloan-Pangasinan noted by Scott and Keesing to be vital in the paper of ethnohistories, continue to exist through the living artefact which is the cattle caravan trade. Locating the cattle caravans of ancient Caboloan is also an attempt at reconstructing local history. Journeying through the caravan routes from the heart of Caboloan to Metro Manila, the cartwheel connects culture and commerce from the village to the metropolis. The cattle caravans’ anachronism in today’s world market economy becomes an assertion of locality and ethnicity in the face of the hegemonic ethnonational and the reifying global system. While the province of Pangasinan is valuated in political terms because of its significant voting population, its ethnocultural history and reality is perceived to be merely subsumed under the mythic kingdom of the Greater Ilocandia. Thus, the cattle caravans serve both as a romantic symbol of an ancient Caboloan culture and as an ethnocultural text amidst the flux of emerging societies and economies. The Philippines is said to be a ‘bamboo country’ because of its swampy coasts and rivers. Historian Isagani Medina lists several place-names which pay tribute to the bamboo such as Meycauayan in Bulacan, Pasong Kawayan in General Trias, Cavite, Cauayan in Negros Occidental and Caoayan in Ilocos Sur. To add to this list is Caboloan of the interior plains of Pangasinan. While the bamboo industry is spread out in different parts of the archipelago, it is only in Caboloan where the tradition of transporting bamboo-based products through the cattle caravan persists up to this day and age. Tourism takes delight in this seemingly quaint, exotic, museum piece of cattle caravans parading at the outskirts of Manila which are occasionally used to attract foreign tourists. The Tourism office however fails to look at the caravan beyond its cultural significance. In Pangasinan alone, handicraft industry is boasted as the top dollar earner. Ironically, the industry does not translate to the upliftment of small handicraft family businesses, more so, the mercantile needs of viajeros of the cattle caravan. It is the class of middlemen and big-time exporters who benefit from its economic advantages, citing Pepe Ferrer’s phenomenal success. Viajeros and handicraft makers alike succumb to loans with interests which middlemen force on them. In the end, they become indebted for life. The cattle caravan is merely a recipient of reject products which did not pass the export standard NACIDA has established during Marcos time. Today, young, aggressive and mostly Chinese entrepreneurs are the ones which replaced the NACIDA, as exporters of bamboo-based products. The rejects from this exporting companies are the ones which trickle down the local market including those peddled by the caravan traders. The debilitating effect of the plastic wares’ competition against the bamboo in recent times heightens the already disadvantaged position of small merchant traders. How will globalization affect the cattle caravans of Ancient Caboloan? Will the world economic system submerge it by its gigantic tentacles from first world capitalists? Will it be obscured by dominant cultures? Or will its recuperative nomenclature ‘glocalization’ recognize the distinctiveness of its existence? Locating the caravans of Caboloan in the context of globalization, this researcher finds the persistence of feudal culture in an age of robust commercialization and industrialization. Conclusion In summary, this ethnocultural mapping is deemed important because it privileges the articulation and the lifeways of the folk and how their stories, narratives and thought patterns intersect in the elite construction of Pangasinan history. With this presentation, I hope that it deepened somehow your understanding of the popular cultural archetypes such as Princess Urduja and the Virgin of Manaoag. Furthermore, I hope that it gave you a sense of pride in terms of our roots and origins through the anachronistic cattle caravan and the earlier historical and trading relations between the coastal Panag-asinan and the interior Caboloan. This general introduction to the study of Pangasinan is also hoped to expand the limited texts that we have. While we do have many schools and universities in Pangasinan concentrated mostly in Dagupan such as the University of Luzon, University of Pangasinan, the Lyceum Northwestern, MotherGoose Science High, etc., among many others including IT learning centers, the knowledge about the province of Pangasinan and appreciation of its culture and history are still wanting. As in the national capitol region, our students are taught, trained and groomed for the global labor market. This is not at all bad. However, as educators we have the responsibility to instill in them a sense of identity and rootedness. Leaving the country for greener pastures is understandable in the context of our lives under a third world economy. But I still dread the day when all Pangasinan folk would have migrated elsewhere. This reminds me of the controversial Pozorubbio.com where the entire folk of this sleepy Pangasinan town has been virtually transplanted into a cyber community. In this age of globalization and transnationalism, Pangasinan folk has joined the peripatetic Ilukanos and the rest of the Filipinos in the greatest diaspora ever from the 20th century to this millenium. The Filipino exile abroad will only become alone if he has been totally uprooted from his native soil. But if his soul brings him to his roots even in a foreign land, he will forever remain Filipino or Pangasinan wherever he may be. It is up to us educators how to put forth that Pangasinan soul in a world of negotiables and consummables.