The College of Creative Studies at the University of California, Santa

advertisement

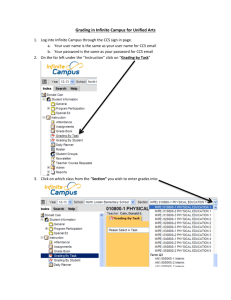

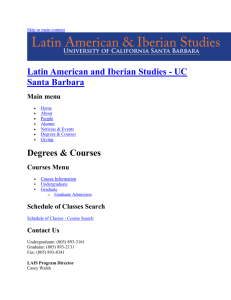

Enhancing student creativity in colleges and universities: the organizational perspectives University System of Taiwan March 2005 William J. Ashby Provost, College of Creative Studies University of California, Santa Barbara USA The College of Creative Studies (CCS) is a small undergraduate college on the Santa Barbara campus of the University of California (UCSB). It enrolls a total of 325 students, less than two percent of the undergraduate students at UCSB. The total enrollment at the Santa Barbara campus, including both graduate students and undergraduates is approximately 20,000. The College of Creative Studies opened its doors to the first class of 50 students in 1967. The mid 1960’s was an era in which students across the United States were complaining about large, impersonal classes, bland introductory courses, and lack of contact with the faculty. Many institutions of higher education sought to develop new undergraduate programs, motivated in part by altruism but also by what historian Robert Kelley termed “an angry national upwelling of student discontent ...”1 At the 2002 Conference on “Undergraduate Research and Scholarship and the Mission of the Research University”, sponsored by the Reinvention Center of the State University of New York at Stony Brook, it was noted that “support and demands from the external environment” is one of the prerequisite factors for change within the context of an organization.2 There can be little doubt that the impetus provided by societal discontent in the 60’s was a key factor that led to the new models such as the College of Creative Studies. A second prerequisite factor for implementing organizational change is “awareness and acceptance that there is a problem to be solved.”3 The vociferous agitation of undergraduate students at UCSB in the early 60’s was clear indication that something was wrong. 1 Robert Kelley, Transformations: UC Santa Barbara 1909-1979. Santa Barbara: The Associated Students, University of California, Santa Barbara, 1981, p. 30. 2 ‘Scaling up and sustaining successful approaches’, moderated by Susan G. Forman. http://www.sunysb.edu/Reinventioncenter/conference 3 ibid. 2 The College of Creative Studies was established at the instigation of former UCSB Chancellor Vernon I. Cheadle, who asked Professor of English Marvin Mudrick to draft an academic plan for a small college within UCSB that would provide an alternative to conventional undergraduate education. The College of Creative Studies was in fact one of several alternative undergraduate colleges proposed at UC Santa Barbara, but was ultimately the only one to be established. Mudrick was named the first Provost in 1967 and served in that capacity until 1984. The College of Creative Studies became what Robert Kelley calls “one of the more enduring and successful educational innovations of the 1960s.”4 Chancellor Cheadle and Professor Mudrick met regularly over breakfast to discuss plans for the new College. The fact that Chancellor Cheadle not only lent his support but was intimately involved in the academic planning was, of course, significant. Organizational innovation requires “resources to support the innovation.”5 The Chancellor’s involvement guaranteed that the 4 Robert Kelley, Transformations: UC Santa Barbara 1909-1979. Santa Barbara: The Associated Students, University of California, Santa Barbara, 1981, p. 31. 5 ‘Scaling up and sustaining successful approaches’, moderated by Susan G. Forman. http://www.sunysb.edu/Reinventioncenter/conference 3 resources would be provided. At the same time, organizational change cannot effectively be imposed from on high. Professor Mudrick’s persuasive charisma was instrumental in getting buy-in from other interested faculty across the range of disciplines that were incorporated into the College’s curriculum. The faculty had to be convinced that there was an advantage to change. The fact that the College of Creative Studies was to be integrated into the organizational structure of UCSB would facilitate its successful development. The CCS model, though innovative in American undergraduate education, was loosely based on the tutorial program of Oxford and Cambridge, which has proved durable. Mudrick disliked much about American undergraduate education, at least that of his time. He especially disliked the highly structured curriculum that required students to take large introductory courses of lecture format before moving on to more advanced material. In the College of Creative Studies, requirements and prerequisites would be as minimal as possible, allowing students to focus intensively on research and creative endeavors that were the center of their passion. The curriculum would be flexible and tailored 4 to the needs and interests of the individual student. The role of the faculty would be not so much to transmit information, as to guide and mentor the student. There would be no lecture courses, but, rather, small seminars, studios, tutorials, and labs where students would be fully engaged in the learning process. Students would be encouraged to find answers for themselves, rather than being told the answers by the faculty. UC Berkeley astrophysicist Alexei Filippenko reminisces about how he learned physics in the College of Creative Studies: The College taught me early to have an open, inquiring, and creative mind, but at the same time one that is logical and critical. This had a lasting and positive influence on my development as a scientist. Some of us, for example, were given a quantity such as the surface tension of water to measure in our first year, but we couldn't look up anything about it in books. We had to figure everything out for ourselves, as though no one had previously worked on this.6 Mudrick’s ideas were quite revolutionary in American education in 1967. Indeed, it took over thirty years for undergraduate research 6 College of Creative Studies Commencement address, June 2000. 5 and creative activity to come to the forefront of national discourse on undergraduate education. In 1998 the Boyer Commission on Educating Undergraduates in the Research University (funded by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching) issued a report entitled Reinventing Undergraduate Education: A Blueprint for America’s Research Universities. The first recommendation of the Boyer Commission was to “make research-based learning the standard” of undergraduate education.7 The Commission prefaced its recommendation by unknowingly echoing Mudrick’s thoughts: Undergraduate education in research universities requires renewed emphasis on a point strongly made by John Dewey almost a century ago: learning is based on discovery guided by mentoring rather than on the transmission of information. Inherent in inquiry-based learning is an element of reciprocity: faculty can learn from students as students are learning from faculty….The experience of most undergraduates at most research universities is that of receiving what is served out to them. In one course after another they listen, transcribe, absorb, and repeat, essentially as undergraduates have done 7 http://naples.cc.sunysb.edu/Pres/boyer 6 for centuries. The ideal embodied in this report would turn the prevailing undergraduate culture of receivers into a culture of inquirers, a culture in which faculty, graduate students, and undergraduates share an adventure of discovery. The College of Creative Studies, then, was something of a pioneer, thanks to the foresight of its founding fathers. Its basic philosophy and structure have not changed much since the inception of the College. The College of Creative Studies is not an independent entity, but is part of the University of California at Santa Barbara. However, there can be little doubt that a key to its success and its longevity is that it is not a program belonging to another academic unit at UCSB, but is indeed a college. In terms of organizational structure, this means that the Provost of the College of Creative Structure reports directly to the Executive Vice Chancellor, from whom the College receives its budget. The Provost of the College of Creative Studies is fully involved in high level administrative discussions, assuring that the interests of the college are represented. Students eligible to attend a campus of the University of California must be in the top twelve and a half percent of their high 7 school class. Admission to the College of Creative Studies is even more selective, and requires a separate application in addition to the application for study at the University of California. Approximately half of those who apply to CCS are accepted for admission. Students targeted by our recruiting efforts are not only unusually bright and talented, but also are passionately committed to pursuing intensive work focused on one of eight disciplines: art, biology, chemistry, computer science, literature, mathematics, music composition, and physics. Once students enroll in the College of Creative Studies, our mission is to guide and support them in the pursuit of their passion, so that they are able to do creative and truly original work as soon as possible. This may be most obvious in art, literature and music composition, where students can begin producing original work as entering freshmen. Indeed, they have already done original work, some of which was included in the portfolio they submitted with their application for admission. In the sciences, additional background study is sometimes first required. Biology students interested in ecology, evolution and marine biology typically engage in original field or laboratory work by the end of their freshman year, if not sooner; 8 those wishing to pursue research in molecular, cell and developmental biology can usually do so by the end of the second year. In the Computer Science, Mathematics, and Physics programs, the necessary background is provided by a series of intensive and accelerated courses in CCS, which allow students to go on to the UCSB departments for upper-division and sometimes graduate courses. In Computer Science and Mathematics, the CCS courses prepare students for advanced work roughly a year sooner than majors in the departments. In Physics, there is a two-year accelerated and intensive course; students then go on to upperdivision and frequently graduate courses in the department. The Biology program provides a freshman colloquium to prepare freshmen students for research. In the Chemistry program, there is a series of laboratory courses specifically for CCS students. These special courses are designed to accelerate the progress of each student along his or her creative trajectory. Most undergraduate students in American universities do not have the opportunity to engage in original work much before their senior year, if at all. By contrast, CCS endeavors to involve its students in the creative process early on, so that they have at least 9 two or three years to engage in original research and creative activity before graduation. In CCS, there are no lecture classes. Instead, CCS offers innovative seminars and tutorials in each of the eight emphases. There are relatively few courses listed in the official UCSB Catalog, and they have rather bland titles. However, the actual content of the course varies from year to year. For example, Biology 101 is officially entitled “Models and Experiments.” Under this general rubric, courses in recent years have ranged from Evolutionary Medicine to Systematics of Seed Plant Families. Literature 113 (Subjects and Materials) has actually encompassed courses as diverse as Demons in Early Western Literature and Japanese and Chinese Poetry. Thanks to this curricular structure, faculty are not obliged to teach pre-existing courses. They do not require a long lead-time to develop new courses. New courses can be instituted quickly, following closely upon the evolution of faculty research interests and student demand. This structure ensures that faculty are teaching courses that they and their students care passionately about. 10 In addition to courses focusing on the eight disciplines represented in the CCS curriculum, we occasionally offer along courses of general that are designed to stimulate interdisciplinary dialog. These are offered under the rubric of General Studies 120 “Advanced Group Interdisciplinary Studies.” Some recent examples of actual courses taught under this rubric are Creative Thinking, the Magic of Ideas; What's Bugging You? (painting and entomology); The Physics of Musical Sound; Flowers (painting and botany); Dance, Music and the Related Arts. The College of Creative Studies has a grading system that may be unique in American higher education. At UCSB, as at most American institutions of higher education, faculty traditionally assign grades ranging from A to F, based on their judgment of the quality of the student’s work. The problem with this system is that students tend to compete with one another for the top grades, rather than working collaboratively. Students tend to focus more on the grade than on creatively applying the material and consequently making it their own. In most American universities, over time there has been grade inflation, making the letter grade less meaningful than in the past. 11 Instead of letter grades, the College of Creative Studies has a system of pass/no record grading. If the student accomplishes work of good quality, work that would normally earn at least a B grade, he or she will receive a “Pass”. If the student drops the course, for whatever reason, it simply does not appear on his or her record. Creative Studies students may drop courses up to the last day of instruction, the same deadline that is given to graduate students. A second component of the CCS grading system is variable units. When students register for a Creative Studies class, they indicate the number of units they expect to earn, typically 4 units. (A total of 180 units are required for graduation.) However, at the end of the course, the instructor assigns the number of units that he or she believes the student has earned. If the student has accomplished a good body of work, but of insufficient quantity to merit 4 units, the instructor can assign fewer. If the student has accomplished work that is particularly impressive in qualitative and quantitative terms, the instructor can assign 5 or 6 units. The system of Pass/No record grading, along with late drop deadline, is intended to encourage students to take risks without worry of penalty. The willingness to take risks, rather than follow the 12 known, safer path, is a well known characteristic of creative people. We want to encourage students to take advanced courses for which they may not have the conventional background, and to take a wide range of courses. We want them to see connections among disciplines. The freedom to drop courses without penalty is an important stimulus to creativity, while the system of variable units allows the faculty to reward students who are unusually ambitious. CCS students take courses not only in the College of Creative Studies, but may select from among the wide range of courses taught in the many academic departments at UCSB. In fact, in the sciences, students take most of their course work from the departments, as CCS cannot pretend to duplicate the laboratories and specialized research equipment that our top-ranked science departments can provide. However, CCS students are not obliged to follow the prescribed curriculum that is set for most undergraduates at UCSB. They do not necessarily have to take courses in the prescribed order, and they do not necessarily have to take courses that are normally prerequisites to more advanced courses. They may elect to take graduate courses, if the instructor permits them to enroll. They may apply courses taken from several academic departments. For 13 example, a CCS literature major may elect courses not only from the English Department, but from any of the other academic departments at UCSB that offer courses focusing on literature. A CCS chemistry major might elect courses taught by the Department of Molecular, Cellular, and Development Biology, or from the Department of Materials Science, in addition to those taught in the Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry. This flexibility in curriculum is possible only because of the academic advising system in the College of Creative Studies. Each entering student is assigned a faculty advisor, with whom the student is required to meet at least once per quarter. The advisor helps the student to select courses, to plan long-term academic goals, and to find enriching opportunities for research and creative activity. CCS alumna, Angela Belcher, is now on the faculty of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She is a leader in the field of nanoscience who was just awarded a MacArthur “genius” Fellowship. She speaks of the role that a flexible curriculum and support from a mentor had in launching her career: I…remember looking through the catalog and finding what I thought was the most interesting class at UCSB. It was a 14 graduate protein chemistry class. So I went to the professor and he said ‘We don’t let undergraduates take this class – besides, you don’t have the prerequisites.’ But the Provost of CCS called him and said, ‘We don’t discourage our students from pursuing what they are interested in, give her a chance’. It was in that class that I really fell in love with large molecules and proteins, and set the course for my research today8. One of the most unusual aspects of the Creative Studies curriculum is that advanced students can design and teach courses called student colloquia, under the supervision of a faculty member. Mudrick was particularly “fond of” this very innovative feature, which soon became a very popular component of the curriculum. Mudrick notes, “It’s possible…for very bright undergraduate students to have a kind of enthusiasm and a freshness about handling material that maybe some older university teachers don’t have.”9 Recent examples of colloquia devised and taught by Creative Studies students include “Modern Scottish Literature”, “How Science Works: The Nature of Discovery”, ”Virtual Machines and Language Translation”. 8 College of Creative Studies Commencement address, June 2003. Lance Kaplan (ed.), Mudrick Transcribed: Classes and talks by Marvin Mudrick. Santa Barbara: College of Creative Studies, 1989, p. 345. 9 15 Alumnus Alexei Filippenko writes about his experience in the following terms: One of my most important experiences in CCS was being allowed to teach a full-year seminar on introductory astronomy to a small group of students. I saw how rewarding it can be to teach, and I recognized various gaps in my own knowledge. All scientists should be able to communicate difficult concepts to the public, and I got a great head start through CCS. Taking and teaching classes, however, is only part of the CCS experience. What Neil Gershenfeld writes about the MIT Media Laboratory characterizes equally well the philosophy of the College of Creative Studies: The formal structure [of the conventional curriculum is] valuable, but as a means rather than an end…Rather than start with the presumption that all students need most of their time filled with ritual observance, the organization of the Media Lab starts by putting them in interesting environments that bring together challenging problems and relevant tools, and then draws on more traditional classes to support that enterprise. The faster the world changes, the more precious these 16 traditional disciplines become as reliable guides into unfamiliar terrain, but the less relevant they are to organize inquiry. CCS offers a number of special programs and facilities designed to support the initiatives of our students. Original work in the sciences is facilitated by the Creative Studies Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship program (SURF), for which sophomore and junior students who conduct research under faculty supervision can compete. The SURF provides a stipend sufficient to allow students to remain at UCSB during the summer and to work full-time on their research project. Typically, SURF participants become part of a faculty-directed research team, working side-byside with graduate students, post-docs, and faculty members; they sometimes graduate having authored or co-authored professional publications. Most of the funding for the SURF program is taken from the operating budget of the College of Creative Studies. This has become increasingly difficult in recent years, since the University of California has suffered three consecutive years of budget cuts. Fortunately, supplemental funding for the SURF program has come from private gifts. 17 Support from the State of California, once providing nearly all of the university's budget, now underwrites just over one-third of UCSB's total expenditures. At UCSB, State appropriations are designated for fundamental expenses. UCSB must secure additional funds in order to maintain the excellence for which it is known throughout the world. Private philanthropy provides that margin of excellence, and plays a significant and increasing role in shaping the university's reputation for teaching and research. Consequently, CCS employs a half-time Development Officer, who works to secure supplemental funding from individuals and foundations. We have been particularly successful in interesting donors in supporting the SURF program, because we can demonstrate the effect of the program in launching the budding research careers of our exceptional students. Gifts from donors also help provide laboratory supplies needed for student research projects and other special projects and opportunities. For example, this past academic year, two CCS students had papers accepted for presentation at professional conferences. A literature major, Ryan Mehan, presented a paper entitled "The Saga of Their Wanderings: Inquiries Into Roma 18 Nomadism" at the Hawaii International Conference on the Humanities. Jay Freeman, a computer science major, delivered a paper entitled "jMonitor: Java Runtime Event Specification and Monitoring Library" at the Runtime Verification ’04 conference in Barcelona, Spain. These are not conferences for undergraduate students, but regular professional conferences. Indeed, Ryan and Jay were the only undergraduate students presenting original papers at these events. Since State funding cannot be used for this purpose, gifts from donors again make a critical difference in the career of these exceptional students. Two literary journals are sponsored by the College of Creative Studies: Spectrum and Into the Teeth of the Wind. These journals are entirely student run, although each has a faculty advisor. The students select from among the many submissions received not only from local students and faculty, but from writers across the country and indeed around the world. The journals are entirely edited and marketed by CCS students, as well. Donor funding is also used to support these endeavors. The Creative Studies Gallery is a showcase for student art work. All art students are required to hold a senior exhibition in the 19 Gallery. Similarly, Music Composition majors are required to have a senior recital of their works, usually held in the Old Little Theater, which belongs to CCS. UCSB provides additional support for undergraduate research and creativity, under the umbrella of the Office of Undergraduate Research and Creative Activity. This is a clearing house for the administration and promotion of various campus-wide programs fostering undergraduate research and creative activity, headed by the Associate Dean of Undergraduate Studies. Students are eligible to apply for small grants (ranging up to $500). A faculty committee evaluates the research proposals. Every spring, a poster session is organized, where students who have received the grants present the results of their projects. The winning entries receive small cash prizes. The Office of Undergraduate Research and Creative Activity also coordinates the Faculty Research Assistance Program. UCSB Faculty members interested in involving undergraduate students in their research projects can post a description of the research project and opportunity for undergraduate involvement on the website of the Office of Undergraduate Research and Creative Activity. One 20 hundred eleven UCSB faculty members currently have posted such opportunities. In his book, Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi states that the question, “Where is creativity?” is more relevant than the question, “What is creativity?”10. True creativity does not take place in a vacuum, in the psyche of the creative individual alone, but in a social matrix. An important element of the success of the College of Creative Studies is the Creative Studies building itself. While it is an old building, inadequate in many ways, it occupies a central location on the UCSB campus and provides not only classrooms and faculty offices, but much more importantly, it is a point of attraction for the CCS students. Students can have a key to the building and they can use it whenever they wish. And use it they do. A mid-night walk through the building will find students clustered in study groups in the classrooms, chatting in the kitchen, at work in the computer rooms, painting in the art studios, perhaps playing one of several available pianos. 10 10 Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention. New York: Harper Collins, 1996. 21 Giving students twenty-four access to the CCS building is one of the easiest and most effective ways possible to stimulate interdisciplinary dialog among the students and to build a sense of community among students and faculty. Community building is one of the goals of the College of Creative Studies. The academic year begins with an All College Meeting, to which all students and faculty are invited. Following a welcome from the Provost, faculty introduce themselves and talk about classes they are planning to teach. Following the All College Meeting, students meet with the faculty of their chosen discipline. At noon, the entire CCS community reconvenes for the All College Barbecue on the front lawn. Because of the small size of the student body and the close working relationship between faculty advisors and students, communication flows naturally throughout the year. A weekly coffee hour provides an opportunity for interaction among students and faculty of the various disciplines. Communication is facilitated by e-mail and by a bi-weekly events calendar (This Week in CCS). The College of Creative Studies is not a residential college, per se. However, students are encouraged to live in the CCS House, a component of one of the campus residential complexes. 22 The Boyer Commission recognized the importance of community to a successful undergraduate program, noting: …traditions feed the need for a connection with place, a unique campus character. These rituals create an aura for a community of learners comprising all members of the university linked by intellectual interests, community values, and interpersonal relations. The College of Creative Studies could not exist, of course, without an unusually dedicated faculty and without the support of the larger institution. In this sense, CCS is fragile. Not every faculty member at a research university is willing to make the substantial commitment that teaching in the College of Creative Studies requires, not only in terms of time spent in the classroom, but in advising and mentoring students outside the classroom. As Mudrick put it, “you do have to have a mission.”11 Sustaining faculty involvement in an innovative educational institution such as the College of Creative Studies often requires a change in faculty culture. American universities are typically facultycentered. Much of the curriculum and formal organization of the 11 Lance Kaplan (ed.), Mudrick Transcribed: Classes and talks by Marvin Mudrick. Santa Barbara: College of Creative Studies, 1989, p. 354. 23 major largely reflect the research interests of the faculty. Faculty tend to see themselves as purveyors of education to consuming students. Some faculty simply do not believe that undergraduate students are capable of producing creative and original work. Others believe that one must follow a logically structured curriculum, even if this means that some students will be wasting their time on pre-requisite courses focused on material they have already mastered. The ethos of the College of Creative Studies is quite different. My colleague Ian Ross expresses this quite well: The College basically is a place where an idea can flourish, whether the idea comes from the faculty or a student. There’s no authority, there’s no hierarchy, there’s no social strata which will affect ehe evolution of an idea and the birth and development of it. The Boyer Commission report echoes this philosophy while highlighting the benefit that not only students, but also faculty can derive from it: Important ideas rarely come fully-developed from the brain of a single individual…It is one of the functions of a university to provide the context in which ideas can be most productively 24 developed. Bruce Alberts, President of the National Academy of Sciences and a member of the Boyer Commission has referred to the “accidental collisions of ideas” necessary for the continued productivity of faculty, and has suggested that the presence of students provides a “lubrication” that breaks down intellectual barriers between faculty members. When students at every level…join with faculty in common inquiry, the opportunities for “accidental collision of ideas” are optimized. Fortunately, the College of Creative Studies has a core cadre of top faculty who believe in its mission and who are more than willing to devote their time to its cause. However, we don’t have enough of them. As faculty of my generation approach retirement, It is crucial that the faculty reward structure adequately recognize the contribution of those who expend their time and energy on mentoring talented undergraduate students. The most fundamental organizational challenge to establishing and sustaining an innovative institution such as the College of Creative Studies is finding a mechanism that will ensure the participation of interested ladder-ranking research faculty. Three 25 structural modes are possible: 1) the faculty buy-out mode, 2) the incentive mode, 3) the permanent faculty mode. The College of Creative Studies operates on the buy-out mode. That is, CCS transfers money to the academic departments that loan their faculty members to CCS, the intention being that these funds can be used to employ a temporary replacement for the faculty member who is teaching in CCS. The problem with this model is that departments are sometimes reluctant to loan their faculty to CCS. Even if the replacement funds are generous (which, in our case, they are not), departments may see the arrangement as a loss. If they loan to CCS a senior faculty member, the replacement is likely to be a temporary lecturer of perceived lesser quality. Our challenge is to persuade departments that they will derive benefit from creating linkages to CCS. One such benefit is that CCS can be used as a testing ground for new innovative courses that can later be incorporated into the departmental curriculum. Another benefit is that that stellar CCS students may become interested in taking additional courses in the department as a result of the faculty member’s teaching in CCS. 26 The incentive model offers faculty additional compensation for teaching as an overload. While CCS has not followed this model, it has proved successful at UCSB in attracting faculty to teach in the Freshman Seminar Program. Freshman Seminars are limited to 15 students each and are designed to introduce new students to research faculty. The Seminars, which focus on a topic of interest to the faculty member, meet for a total of ten hours per quarter and are give one unit of academic credit. This year, approximately 100 Freshman Seminars are being offered, examples of which are shown on the slide. Faculty volunteer to teach the Seminars in addition to their regular course assignment. In compensation, they receive $1500 in research funds. Of course, teaching a one-hour seminar per week is not a major investment in faculty time and energy, compared to teaching a full course in CCS. There is an advantage to the buy-out and incentive modes. These two modes assure that there develops no dead wood among the faculty. If a given faculty member proves ill-suited to teaching in CCS and to mentoring creative students, he or she is simply not invited back. These modes also allow for a rotation of faculty and 27 consequently provide flexibility to address changing student interests and disciplinary shifts. Despite these advantages, I believe that the permanent faculty mode is superior. Only permanent faculty can become truly vested in the institution. Faculty who are transitory can be stellar teachers and good mentors, but their primary allegiance will always be to their home department with whom their career is vested. There are some ladder faculty who are generous in involving themselves in the governance of the College, but they are the exceptions. The ideal mode is that of joint appointments between CCS and an academic department. This is the mode for which CCS is now advocating in its academic plan. Enhancing creativity in the university setting requires not only the right faculty culture, it also requires the right student culture. Students who are admitted to the College of Creative Studies are not only bright and talented, but also are passionately committed to pursuing intensive work focused on one of eight disciplines: art, biology, chemistry, computer science, literature, mathematics, music composition, and physics. 28 While the typical student entering the College of Creative Studies has high test scores and grades,12 every year the College seeks admission to UCSB by Special Action for a handful of students who otherwise would not qualify for admission. Sometimes such students have poor high school records, because they have been bored and have refused to play the academic game that would have earned them high grades. Sometimes their high school record is very uneven. Sometimes they have suffered personal or family adversity. In cases of Admission by Special Action, the Creative Studies faculty have looked at more than the numbers and have been convinced of the talent and potential of the individual. In most cases, such students go on to do good things in CCS and in later life. When reviewing students for admission, the faculty look above all for promise of creative potential. Identifying appropriate students is not easy. Of course, we consider the high school record in terms of courses taken and grades earned. We also consider the scores students have earned on the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT). We have found, however, that these cannot be the only criteria. Many of the faculty members of the College of Creative Studies would agree 12 in Fall 2003, the average SAT 1 score among new freshmen was 1325; the average high school GPA was 3.71. 29 with physicist Neil Gershenfeld, Director of MIT’s Media Lab, that a high grade point average is not necessarily a predictor of creativity and in fact may be a counter indicator. In discussing the criteria for selecting students for the Media Lab, he says: I look to make sure they have a few F’s [a failing grade]. Students with perfect grades almost always don’t work out, because it means they’ve spent their time trying to meticulously follow classroom instructions that are absent in the rest of the world. Students with A’s and F’s have a much better record, because they’re able to do good work, and also set priorities for themselves. They’re the ones most able to pose—and solve— problems that go far beyond anything I might assign to them.13 When students apply for admission to the College of Creative Studies, they must include a letter of intent, addressed to the Provost, in which they are invited to articulate their goals and reasons for studying in the College of Creative Studies. They must also secure letters of recommendation from their high school teachers. The faculty in the program to which the student applies read these texts carefully for evidence that the student is not just smart and good at 13 Neil A. Gershenfeld, When Things Start to Think. New York: Henry Holt, 1979, p. 188. 30 taking tests, but that he or she is truly committed to pursuing advanced and independent work. Students applying for study in the arts must submit a substantial portfolio of their creative work. Sometimes students will be interviewed in person or on the telephone. As a means both of identifying appropriate students and of judging their creativity, CCS also conducts three Prize Competitions for high school students every year. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi notes that one of the characteristics of creative people is an early interest in a particular subject.14 Another characteristic of creative people is an uncommon curiosity and love for the subject. These are the characteristics we look for among prospective students. An example of the focused and passionate individual attracted to CCS is a student I will call “Octopus Girl.” In her Statement of Intent, Octopus Girl writes: I have always been a hands-on, independent learner, and I am excited to think that even as an undergraduate I would be able to do original research…My love for the ocean is expressed in almost everything I own, from clothes to books, from clocks to 14 Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention. New York: Harper Collins, 1996. 31 stationary. I am sometimes called Octopus Girl at school, due to my well-known interest (obsession?) in these remarkable cephalopods. In fact, I have kept several pet octopuses, as well as seahorses and anemones, for which purpose I purchased a sixty-gallon tank several years ago. At the College of Creative Studies, Octopus Girl, whose real name is Danna Schulman pursued her research interests in marine science. She graduated last fall and is now pursuing a Ph.D. in marine biology at Stanford University. As I stated earlier, the College of Creative Studies enrolls less than two percent of the undergraduate students at UC Santa Barbara. It is something of an elite institution, a meritocracy for students with unusual talent, focus and drive. For students who have their own creative vision. Not all students who enter UCSB are as focused and passionate as Ms. Octopus, of course. In fact, many students are quite, more solitary learners. These students often say that they prefer the anonymity of the large lecture class. They expect the faculty to be purveyors of knowledge and see themselves as consumers. They are sometimes fiercely competitive and care less 32 about creativity than about earning a good grade. Is there a way to apply the lessons of the College of Creative Studies on a larger scale so as to encourage creativity among such students? Can we change the prevailing student and faculty culture so as to enhance creativity? This is not easy to accomplish, even in the context of an American university. It may be more difficult to accomplish in Taiwan, where traditions and prevaling cultural patterns are quite different than those in the United States. The Boyer Commission suggests ten relevant goals that can guide institutions in reforming undergraduate education. Most of these goals have guided the College of Creative Studies for nearly forty years. We have not been able to realize all of them to our satisfaction, but I believe they offer useful guiding principles. 1) Make research-based learning the standard; 2) Construct an inquiry based freshman year; 3) Build on the freshman foundation; 4) Remove barriers to interdisciplinary education; 5) Link communication skills and course work; 6) Use information technology creatively; 7) Culminate with a capstone experience; 33 8) Educate graduate students as apprentice teachers; 9) Change faculty rewards systems; 10) Cultivate a sense of community. These goals can serve as useful guidelines for developing academic programs and organizational structures that will support creative collaborations between students and faculty. 34