Evidence_Schauer_F2008 – Outline

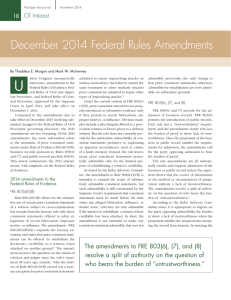

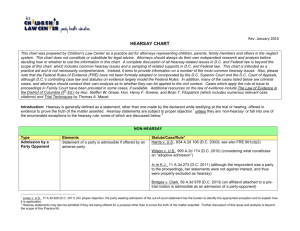

advertisement