Strategic Personality and the Effectiveness of Nuclear Deterrence

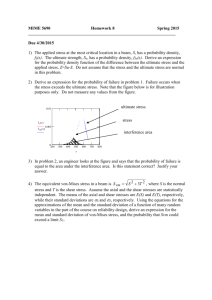

advertisement