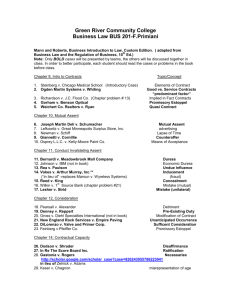

Contracts - CONTRACTUAL CAPACITY

advertisement

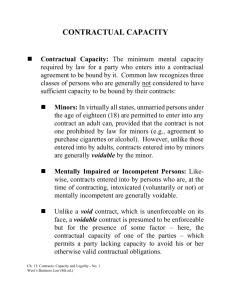

CONTRACTUAL CAPACITY Contractual Capacity: The minimum mental capacity required by law for a party who enters into a contract to be bound by it. Certain persons are generally not considered to have sufficient capacity to be bound by their contracts: Minors: In virtually all states, unmarried persons under the age of eighteen (18) are permitted to enter into any contract an adult can, provided that the contract is not one prohibited by law for minors (e.g., agreement to purchase cigarettes or alcohol). However, unlike those entered into by adults, contracts entered into by minors are generally voidable by the minor. Mentally Impaired or Incompetent Persons: Likewise, contracts entered into by persons who are, at the time of contracting, intoxicated (voluntarily or not) or mentally incompetent are generally voidable. Unlike a void contract, which is unenforceable on its face, a voidable contract is presumed to be enforceable but for the presence of some factor – here, the contractual capacity of one of the parties – permitting a party lacking capacity to avoid his otherwise valid contractual obligations. Ch. 8: Contracts: Capacity, Legality, Assent, and Form - No. 1 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) MINORITY: DISAFFIRMANCE Disaffirmance: Legally avoiding or setting aside a contractual obligation. In order for a minor to avoid a contract, he need only manifest an intention not to be bound by it. Generally speaking, a minor may disaffirm a contract at any time during minority or for a reasonable time after the minor comes of age. When a minor disaffirms a contract, he can recover all property that he has transferred as consideration – even if it was subsequently transferred to a third party. Upon disaffirmance, a majority of states require only that the minor return any goods or other consideration in his possession. However, a growing number of states further require that the minor take whatever additional steps are required to restore the adult to the position he was in prior to entering the contract. Only the minor has the option of disaffirming his contractual obligations; any adult parties to the contract remain bound by it unless released by the minor’s disaffirmance. Ch. 8: Contracts: Capacity, Legality, Assent, and Form - No. 2 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) MINORITY: EXCEPTIONS Misrepresentations Regarding Age: Most states will permit disaffirmance even if the minor misrepresented his age when entering into the agreement. However, some states prohibit disaffirmance in all cases where the minor misrepresented his age, prohibit disaffirmance in cases where the minor has engaged in business as an adult, refuse to allow minors to disaffirm fully performed contracts, unless they can return all consideration received, or permit disaffirmance but subject the minor to tort liability for his misrepresentation. Liability for Necessaries: A minor who enters into a contract to purchase food, shelter, clothing, medical attention, or other goods or services necessary to maintain his well-being will generally be liable for the reasonable value of those goods and services even if he disaffirms the contract. Ch. 8: Contracts: Capacity, Legality, Assent, and Form - No. 3 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) INTOXICATION Intoxication: A condition in which a person’s normal capacity to act or think is inhibited by alcohol or some drug. If a party was so intoxicated at the time she entered into a contract as to lack the ability to comprehend the legal consequences of entering into the contract, then she may avoid the contract, even if her intoxication was purely voluntary. Most courts will look for objective indications that the allegedly intoxicated party possessed or lacked the necessary capacity – e.g., negotiating the terms of the contract, committing it to writing, etc. Disaffirmance: If a party is entitled to avoid her contract due to intoxication, she may disaffirm it, in the same way as a minor. However, unlike a minor, she will likely be required to make full restitution to the other party before being allowed to disaffirm. Ch. 8: Contracts: Capacity, Legality, Assent, and Form - No. 4 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) MENTAL INCOMPETENCE Contracts made by mentally incompetent parties may be void, voidable, or valid, depending on the circumstances. Void Contract: A party who has been adjudged mentally incompetent by a court of law prior to entering into a contract, and who has a court-appointed guardian, cannot enter into a legally binding contract – only the guardian may enter into binding contracts on behalf of the incompetent party. Voidable Contract: A party who has not been adjudged mentally incompetent by a court of law may, nonetheless, avoid a contract if, at the time of contracting, he (1) did not know he was entering into a contract or (2) lacked the mental capacity to understand its nature, purpose, and consequences. Only the incompetent party has the option of disaffirming his contractual obligations; any competent party to the contract remains bound unless released by the incompetent party’s disaffirmance. Valid Contract: An otherwise incompetent party who understood the nature, purpose, and consequences of entering into the contract is bound by it. Ch. 8: Contracts: Capacity, Legality, Assent, and Form - No. 5 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) RATIFICATION Ratification: Accepting and giving legal force to an obligation that previously was (1) not enforceable or (2) voidable. Ratification may be either express or implied. Express Ratification: A person lacking contractual capacity at the time they formed a contract may, upon (re-)gaining the necessary capacity to do so, expressly ratify the contract by stating, orally or in writing, that they intend to be bound by the contract. Implied Ratification: Likewise, a person lacking contractual capacity at the time they formed a contract may, upon (re-)gaining the necessary capacity to do so, impliedly ratify the contract (1) by acting in a manner that is clearly inconsistent with disaffirmance or avoidance, or (2) in the case of a minor, by failing to disaffirm within a reasonable time after reaching the age of majority, or (3) in the case of an intoxicated person, by failing to disaffirm within a reasonable time after regaining sobriety. Ch. 8: Contracts: Capacity, Legality, Assent, and Form - No. 6 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) CONTRACTS CONTRARY TO STATUTE Statutes sometimes proscribe certain types of contracts or contractual provisions. For example: Usury: Virtually every state has a statute that sets the maximum rate of interest that can legally be charged for different types of transactions, including ordinary loans. Usurious contracts are illegal, and may be void in their entirety, although most states simply limit the interest the lender is permitted to collect. Gambling: Most gambling contracts are illegal and void, even in states where certain forms of regulated gambling are permitted. Blue Laws: Some states and localities prohibit engaging in certain business activities on Sundays. Licensing: All states require that members of certain professions (e.g., attorneys, doctors, architects) be licensed by the state. A contract with an unlicensed individual may be enforceable unless made unenforceable by (1) statute or (2) public policy, as evidenced by the reasons underlying the licensing statute. Ch. 8: Contracts: Capacity, Legality, Assent, and Form - No. 7 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) CONTRACTS IN RESTRAINT OF TRADE Contracts in Restraint of Trade: Contracts that tend to reduce competition for the provision of goods or services in a market (e.g., covenants not to compete). Restrictive Covenants in the Sale of a Business: Many agreements for the sale of an ongoing business require the seller not to open a competing business within a specified area including the business being sold. To be enforceable, the geographic restriction must be reasonable, and must be effective only for a reasonable period of time after the sale is completed. Restrictive Covenants in Employment Contracts: Many employment agreements, likewise, require the employee to refrain from working for a competitor or starting a new business in competition with the employer for a reasonable period of time, and within a reasonably defined geographic area, after the employment relationship ends. A restrictive covenant is generally permitted when it is ancillary to an otherwise enforceable contract. If it is not ancillary to an otherwise enforceable contract, or if the terms of the covenant are too restrictive, the covenant will be void. Ch. 8: Contracts: Capacity, Legality, Assent, and Form - No. 8 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) OTHER CONTRACTS CONTRARY TO PUBLIC POLICY Unconscionable Contracts: Contracts that contain terms that are unfairly burdensome to one party and unfairly beneficial to the other. Procedural Unconscionability: Arises when one party to the contract lacks or is deprived of any meaningful choice regarding the terms of the contract due to inconspicuous print, unintelligible language, lack of opportunity to read the contract before signing, or lack of bargaining power. Substantive Unconscionability: Arises when the contract contains terms that deprive one party of the benefit of its bargain or of any meaningful remedy in the event of breach by the other party. Exculpatory Clauses: A contractual provision releasing a party from liability, regardless of fault. Ch. 8: Contracts: Capacity, Legality, Assent, and Form - No. 9 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) EFFECT OF ILLEGALITY A contract that is contrary to statute or to public policy is, generally, void; and, therefore, unenforceable. In most cases, both parties to a void contract are considered to be equally at fault (in pari delicto), and therefore cannot enforce the contract against the other party. There are some exceptions: Justifiable Ignorance: When one of the parties to an illegal contract has no knowledge or any reason to know that the contract is illegal, that party will be entitled to be restored to its pre-contractual situation. Protected Classes: When a statute protects a class of people, a member of that class may enforce an otherwise illegal contract, even though the other party cannot. Withdrawal from an Illegal Agreement: If a party withdraws from a partial agreement before any illegality occurs, she may recover its value to her. A party induced to enter an illegal contract by fraud, duress, or undue influence may either enforce the contract or recover its value to her. Severability/Divisibility: If the contract can be divided into legal and illegal parts, a court may enforce the legal part(s) but not the illegal one(s). Ch. 8: Contracts: Capacity, Legality, Assent, and Form - No. 10 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) GENUINENESS OF ASSENT A party who demonstrates that he or she did not genuinely assent to the terms of a contract may avoid the contract. Genuine assent may be lacking due to mistake, fraudulent misrepresentation, undue influence, or duress. As was true with contracts entered into by persons lacking contractual capacity, contracts lacking genuine assent are voidable, not void. Ch. 8: Contracts: Capacity, Legality, Assent, and Form - No. 11 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) MISTAKE Mistake: The parties entered into a contract with different understandings of one or more material facts relating to the subject matter of the contract. Unilateral Mistake: A mistake made by one of the contracting parties. Generally, a unilateral mistake will not excuse performance of the contract unless: (1) the other party to the contract knew or should have known of the mistake; or (2) the mistake is one of mathematics only. Mutual Mistake of Fact: A mistake on the part of both contracting parties as to some material fact. In this case, either party may rescind. Mutual Mistake of Value: If, however, the mutual mistake concerns the future market value or some quality of the object of the contract, either party can normally enforce the contract. Ch. 8: Contracts: Capacity, Legality, Assent, and Form - No. 12 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) MISREPRESENTATION When an innocent party consents to a contract with fraudulent terms, she may usually avoid the contract, because she did not genuinely assent to the fraudulent terms. Elements of Fraudulent Misrepresentation: (1) A party misrepresented a material fact, (2) with the intent to deceive an innocent party, (3) on which the innocent party justifiably relied, (4) resulting in injury to the innocent party. Predictions and Expressions of Opinion: Generally, these will not give rise to an actionable misrepresentation, unless the person making the statement has a particular expertise and knows or has reason to know that the listener intends to rely on the statement. Ch. 8: Contracts: Capacity, Legality, Assent, and Form - No. 13 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) INTENT, RELIANCE, AND INJURY Scienter: A defendant acts with the intent to deceive if he: (1) knows a statement to be false, (2) makes a statement he reasonably believes to false, (3) makes a statement recklessly, without regard to its truthfulness or falsity, or (4) implies that a statement is made on the basis of information that he does not possess or on some other basis on which it is not, in fact, based. Reliance: The innocent party must have acted based on (although not solely based on) the misrepresentation. Moreover, in many jurisdictions, the innocent party’s reliance on the misrepresentation must be reasonable. Injury: Most courts do not require proof of an injury to the innocent party if the only remedy she seeks is rescission of the contract – that is, returning the parties to their precontractual positions. However, in order to recover damages, the innocent party must prove she was injured by the misrepresentation. Ch. 8: Contracts: Capacity, Legality, Assent, and Form - No. 14 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) UNDUE INFLUENCE AND DURESS Undue Influence arises from relationships in which one party can influence another party to the point of overcoming the influenced party’s free will. The essential feature of undue influence is that the party being influenced does not, in reality, enter into the contract of her own free will. If a contract enriches a party at the expense of another whom the first party dominates or to whom the first party owes fiduciary duties, courts will often presume that the contract was made under undue influence. Under influence is grounds for canceling (or rescinding) the contract. Duress: Forcing a party to enter into a contract because of the fear created by threats to do something wrongful if the party does not agree to the contract. While a party forced to enter into a contract under duress may choose to perform the contract, duress is grounds for rescission. Ch. 8: Contracts: Capacity, Legality, Assent, and Form - No. 15 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) THE STATUTE OF FRAUDS Statute of Frauds: A statute that requires certain types of contracts to be evidenced by a writing in order to be enforceable. The following types of contracts generally must be evidenced by a writing to be enforceable: (1) contracts involving an interest in real property (e.g., a home mortgage); (2) contracts that cannot, by their terms, be performed within one year after the date the contract was formed (e.g., a five-year employment contract); (3) collateral promises, such as promises to answer for or guarantee the debt or duty of another person and promises by an executor or administrator to answer personally for the debts of an estate; “Main Purpose” Rule: If the party who agrees to guarantee the debt of another does so to secure a personal benefit for themselves, the statute of frauds does not require a writing. (4) promises made in consideration of marriage (i.e., prenuptial agreements); and (5) contracts for the sale of goods for $500 or more. Ch. 8: Contracts: Capacity, Legality, Assent, and Form - No. 16 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) THE STATUTE OF FRAUDS: EXCEPTIONS A contract that might otherwise be unenforceable because it is not evidenced by a writing may be enforced to some degree as follows: Partial Performance: If a buyer has taken partial possession of property and paid that part of the contract price attributable to the property received, and if the parties cannot be returned to their pre-contractual positions, a court may order that the remainder of the contract be performed according to its terms. Under the UCC, an oral contract is enforceable to the extent that the seller has accepted payment or the buyer has accepted delivery of the goods covered by the oral contract. Judicial Admission: If a party judicially admits the existence of a contract, the contract is enforceable at least to the extent of the admission. Promissory Estoppel: If a promisor makes a promise on which the promisee justifiably relies to the promisee’s detriment, the promisor may be estopped from denying the existence and validity of the contract despite the lack of a writing satisfying the statute of frauds. Ch. 8: Contracts: Capacity, Legality, Assent, and Form - No. 17 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) FORM OF THE WRITING A written contract, signed by both parties, satisfies the requirements of the statute of frauds. What else will suffice? A writing signed by the party against whom enforcement is sought; An agreement may be signed anywhere on the agreement; moreover, initials, letterhead, a rubber stamp, or even a fax banner may satisfy the signature requirement – as long as the person intended to authenticate the writing by affixing their initials, etc. A confirmation, invoice, sales slip, check, or fax, or any combination thereof; or Several documents which, in combination, provide the terms for an agreement. Ch. 8: Contracts: Capacity, Legality, Assent, and Form - No. 18 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) ESSENTIAL TERMS The writing need only contain the essential terms: (1) the names of the parties, (2) the subject matter of the contract, (3) the amount of property to be sold or leased or services to be rendered, and (4) the consideration given or promised to the party against whom enforcement is sought. Whether price is an “essential” term depends on the type of contract in question. Ch. 8: Contracts: Capacity, Legality, Assent, and Form - No. 19 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.)