contracts - dupre

advertisement

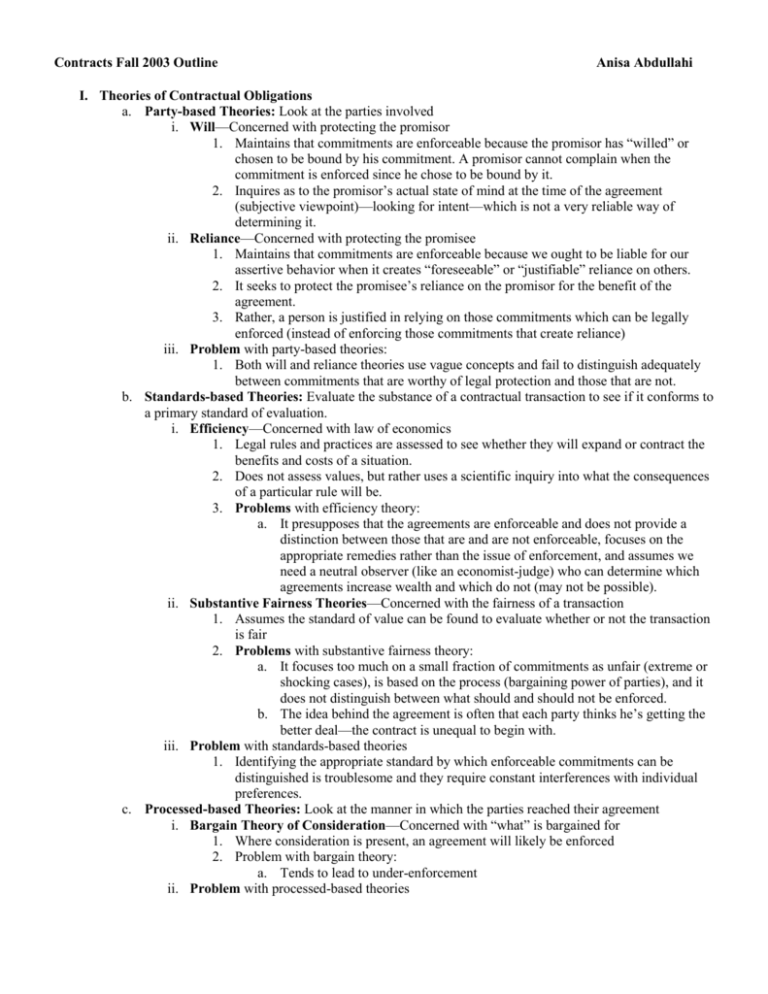

Contracts Fall 2003 Outline Anisa Abdullahi I. Theories of Contractual Obligations a. Party-based Theories: Look at the parties involved i. Will—Concerned with protecting the promisor 1. Maintains that commitments are enforceable because the promisor has “willed” or chosen to be bound by his commitment. A promisor cannot complain when the commitment is enforced since he chose to be bound by it. 2. Inquires as to the promisor’s actual state of mind at the time of the agreement (subjective viewpoint)—looking for intent—which is not a very reliable way of determining it. ii. Reliance—Concerned with protecting the promisee 1. Maintains that commitments are enforceable because we ought to be liable for our assertive behavior when it creates “foreseeable” or “justifiable” reliance on others. 2. It seeks to protect the promisee’s reliance on the promisor for the benefit of the agreement. 3. Rather, a person is justified in relying on those commitments which can be legally enforced (instead of enforcing those commitments that create reliance) iii. Problem with party-based theories: 1. Both will and reliance theories use vague concepts and fail to distinguish adequately between commitments that are worthy of legal protection and those that are not. b. Standards-based Theories: Evaluate the substance of a contractual transaction to see if it conforms to a primary standard of evaluation. i. Efficiency—Concerned with law of economics 1. Legal rules and practices are assessed to see whether they will expand or contract the benefits and costs of a situation. 2. Does not assess values, but rather uses a scientific inquiry into what the consequences of a particular rule will be. 3. Problems with efficiency theory: a. It presupposes that the agreements are enforceable and does not provide a distinction between those that are and are not enforceable, focuses on the appropriate remedies rather than the issue of enforcement, and assumes we need a neutral observer (like an economist-judge) who can determine which agreements increase wealth and which do not (may not be possible). ii. Substantive Fairness Theories—Concerned with the fairness of a transaction 1. Assumes the standard of value can be found to evaluate whether or not the transaction is fair 2. Problems with substantive fairness theory: a. It focuses too much on a small fraction of commitments as unfair (extreme or shocking cases), is based on the process (bargaining power of parties), and it does not distinguish between what should and should not be enforced. b. The idea behind the agreement is often that each party thinks he’s getting the better deal—the contract is unequal to begin with. iii. Problem with standards-based theories 1. Identifying the appropriate standard by which enforceable commitments can be distinguished is troublesome and they require constant interferences with individual preferences. c. Processed-based Theories: Look at the manner in which the parties reached their agreement i. Bargain Theory of Consideration—Concerned with “what” is bargained for 1. Where consideration is present, an agreement will likely be enforced 2. Problem with bargain theory: a. Tends to lead to under-enforcement ii. Problem with processed-based theories 1. They place obstacles in the way of minimizing the difficulty of enforcement, failing to leave room for serious, but unbargained-for, commitments and leaving room for agreements to perform illegal acts as long as they were processed correctly. iii. Advantage over party-based and standards-based theories 1. They employ neutral criterion for determining contractual enforcement. II. Types of Contracts a. Express Contract: An actual agreement of the parties with terms i. Openly declared at the time of making the agreement, and ii. States in distinct and explicit language, either orally or in writing b. Implied in Fact: Contract established by conduct i. Elements of an implied in fact contract: 1. D requested P to perform the work 2. P expected D to compensate him for his services 3. D knew or should have known that P expected compensation ii. Damages can be reliance (as if the contract had existed)—the intended contract price (?) 1. So mechanic would get paid for the service and the products he had to use or buy iii. Bailey v. West: Trainer dropped lame horse at P’s farm after D tried to return it; ownership was in dispute, but P cared for the horse anyhow and sent bills to both owners. No implied in fact contract because D never requested P to care for the horse (in fact, he said he would not pay) and they had never dealt with each other before so that there could be some communication implying a contract. c. Quasi-contract or Implied in Law: Not really a contract, but a legal action in restitution regardless of the intent, privity (mutuality of interest), or promise of the parties i. Elements of a quasi-contract 1. D receives a benefit 2. Appreciation/Knowledge by D of the benefit 3. Unjust for D to retain benefit without paying ii. Wade test for a quasi-contract 1. P did not intend to act gratuitously or officiously 2. P conferred a measurable benefit on D 3. D had a chance to decline the benefit or he had a reasonable excuse for failing to do so iii. The damages are usually restitution (?) iv. Bailey v. West: No quasi-contract either because P failed to give D the opportunity to decline. v. Example: Mechanic hypo, coming up to your car and fixing it for you while you are at a rest stop d. Four types of enforceable contracts i. Promise and consideration ii. Promise and antecedent benefit iii. Promise and unbargained for reliance iv. Promise and form (?) III. Consideration a. Illusory Promise: Not enforceable i. Things to look at to see if a promise is illusory 1. Is the language indefinite? 2. Does one party have complete discretion—does the promise make it optional or entirely discretional on the part of the promisor? a. Example: Insurance company that promised bonuses to workers but reserved the right to not give it. b. Gratuitous Promise: Not enforceable i. A promise given in exchange for nothing; there is no consideration ii. Kirksey v. Kirksey: Brother-in-law said if his brother’s widow would come down and see him, he would let her have a place to raise her family; his promise was a mere gratuity. 1. Might have been consideration if the widow was a guy and the brother-in-law asked him to help him work the land; or if he had asked her to give him companionship. c. Past Promise: Not enforceable i. A promise that is based on something that has already been done in the past (timing problem) ii. Example: Grandfather case where he asked them to name the baby August in exchange for $5000, but they had already named him August (was not induced, had already been done) d. Forbearance: Good consideration i. Abstaining form a legal right you actually have ii. Williston aid: Whether the happening of the condition will be a benefit to the promisor iii. Langer v. Steel: D promised to give P $100 for not working somewhere else and using his skills. Court ruled in favor of P because D was receiving a benefit and P gave up his right to work elsewhere. 1. If he was just getting the money as a gift for being a good worker it would be a gratuitous promise 2. Distinct from Kirksey because the promisor is getting something back (Williston) iv. Hamer v. Sidway: Grandfather asked him to abstain from smoking, drinking, and gambling for $5000 1. If you’re not allowed to do it anyway, it’s not a legal right. 2. If the nephew had just happened to stopped drinking, not knowing about the promise, it would not work either. e. Invalid claim: Can be consideration IF you reasonably think it is a good claim i. Fiege v. Boehm: Woman promised not to bring bastardy suit in exchange for alleged father’s monetary support. At the time she thought he was the father. 1. What would the reasonable person think about the claim; if they reasonably believed they had a claim it is sufficient 2. You can’t forebear from pressing a criminal claim because society wants to punish them. In this case, they said the bastardy suit was civil in nature. ii. R §74: Settlement of Claims 1. (1) Forbearance to assert or the surrender of a claim or defense which proves to be invalid is not consideration unless a. (a) the claim or defense is in fact doubtful because of uncertainty as to the facts or the law, or b. (b) the forbearing or surrendering party believes that the claim or defense may be fairly determined to be valid. 2. (2) The execution of a written instrument surrendering a claim or defense by one who is under no duty to execute it is consideration if the execution of the written instrument is bargained for even though he is not asserting the claim or defense and believes that no valid claim or defense exists. iii. R §79: Adequacy of Consideration a. If the requirement of consideration is met, there is no additional requirement of i. (a) a gain, advantage, or benefit to the promisor or a loss, disadvantage, or detriment to the promisee; or ii. (b) equivalence in the values exchanged; or iii. (c) “mutuality of obligation.” f. Explicit Consideration: Expressed orally or written i. Bogigian v. Bogigian: Ex-wife wrote out that she released her ex-husband from a judgment requiring him to pay her $10,300 upon selling their home. The court does not uphold it, however, because it wasn’t bargained for by the parties. ii. R §71: Requirement of Exchange; Types of Exchange 1. (1) “To constitute consideration, a performance or a return promise must be bargained for. 2. (2) A performance or return promise is bargained for if it is sought by the promisor in exchange for his promise and is given by the promisee in exchange for that promise.” iii. Bargain test of consideration: 1. Quid pro quo: there must be a benefit to the promisor 2. Reliance of special assumpsit: there must be a detriment to the promisee 3. OR: Bargained for exchange g. Implicit Consideration: Implied through words or conduct i. Palmer v. Dehn: Mechanic’s fingers were cut off when driver started bus he was fixing; Palmer promised to pay his expenses. 1. Jury could infer the promisor was seeking something and the promisee was giving something; their actions implied a promise 2. Palmer was probably worried about being sued and his promise could be seen to induce the mechanic to forebear from his right to bring action against him. h. Nominal Consideration: Not enforceable i. In name only; usually people trying to dress something up to be consideration (mere pretense) ii. Thomas v. Thomas: Widow paid $1 rent and kept up land 1. One of the rare instances where nominal consideration was upheld 2. But note that she gave up getting married—the contract said “as she should continue a widow and unmarried” iii. In re Greene: Bankrupt promised his mistress a life insurance policy payment, rent, etc. in exchange for $1 and “other good an valuable considerations” 1. More usual situation where $1 wasn’t enough to constitute an enforceable contract 2. And, no “other considerations” were given i. Value of Consideration: When there is a disparity between the promise and what is given in exchange i. If there is consideration, it doesn’t matter how much it is worth (different than nominal consideration in that it is of something sought for, not a pretense of consideration to dress up a gratuity) ii. R §79: Adequacy of consideration 1. If the requirement of consideration is met, there is no additional requirement of 2. …(b) equivalence in the values exchanged iii. Haigh v. Brooks: D got P to give up a written promise of payment in exchange for an oral promise to pay debt of Lee who D had an interest in. Court didn’t look any more into the difference in value (the paper was worthless because it did not have consideration) 1. It just had to be of some value to the promisor—D believed it was valuable 2. Note that this involved educated parties who were not unequal in bargaining power iv. Apfel v. Prudential-Bache Securities: D bought idea from P regarding computerized book entries for municipal securities and then refused to pay for it because the idea was not novel. 1. Doesn’t have to be novel, just of some value to the promisor 2. Again, educated parties who were not unequal v. EXCEPTION: Unconsciounability 1. Jones v. Star Credit Corp.: Welfare recipients agreed to purchase a home freezer for over $900 when it was worth only $300 retail. They were uneducated (notice conclusion court makes) and there was unequal bargaining power. a. If there is a huge discrepancy or the bargaining power is unequal, unconsciounability might make the contract unenforceable b. UCC §2-302: Unconsciounable Contract or Term i. (1) If the court as a matter of law finds the contract or any term of the contract to have been unconscionable at the time it was made the court may refuse to enforce the contract, or it may enforce the remainder of the contract without the unconsciounable term, or it may so limit the application of any unconsciounable term as to avoid any unconsciounable result. ii. (2) When it is claimed or appears to the court that the contract or any term thereof may be unconsciounable the parties shall be afforded a reasonable opportunity to present evidence as to its commercial setting, purpose and effect to aid the court in making the determination. j. Pre-existing duty: If a party already has a duty to perform the contract, it cannot be consideration without something new i. Voluntary change or modification 1. Levine v. Blumenthal: Leaser agreed to accept a lower rent payment from lessee due the Depression, then sued for the difference still owed. 2. R §73: Performance of a legal (pre-existing) duty owned to a promisor which is neither doubtful or the subject of honest dispute is not consideration; but a similar performance is consideration if it differs from what was required by the duty in a way which reflects more than a pretense of bargain ii. Unanticipated difficulties 1. Angel v. Murray: Refuse collector modified his contract for additional payments of $10,000 per year with the city when a substantial increase in the cost of collection resulted from an unanticipated increase of 400 dwelling units. 2. UCC §2-209: Modification, Rescission, and Waiver a. (1) An agreement modifying a contract within this Article needs no consideration to be binding—applies to GOODS only. 3. R §89: Modification of Executory Contract a. A promise modifying a duty under a contract not fully performed on either side is binding i. (a) if the modification is fair and equitable in view of the circumstances not anticipated by the parties when the contract was made; or ii. (b) to the extent provided by statute; or iii. (c) to the extent that justice requires enforcement in view of material change in position in reliance on the promise 4. Massachusetts rule: If one party agrees not to break the contract, that is consideration 5. Compare to Bolin Farms case (?) iii. Hold-up game 1. Alaska Packers’ Association v. Domenico: Fisherman refused to perform the tasks they were under contract to perform without additional compensation when their employer could no longer obtain new workers and had short window of opportunity to catch the fish due to the season being short. a. Can’t take advantage of a party b. An amendment to a contract will not be enforced if it was made through coercion or by taking unjustifiable advantage of the necessities of the other party. 2. R §73: Performance of Legal Duty a. Performance of a legal duty owed to a promisor which is neither doubtful nor the subject of honest dispute is not consideration; but a similar performance is consideration if it differs from what was required by the duty in a way which reflects more than a pretense of bargain. IV. Mutuality of obligation a. Both parties have to bound in some way by the contract b. Free way out: If one party can breach without consequences, there is no mutuality and no binding contract i. Rehm-Zeiher v. Walker: Whiskey trader contracted with distiller to buy liquor each year for a certain price. c. Output and Requirement contracts i. Output: Buyer agrees to buy what the seller can produce ii. Requirement: Buyer agrees to buy from the seller what he requires 1. UCC §2-306(1) A term which measures the quantity by the output of the seller or the requirements of the buyer means such actual output or requirements as may occur in good faith, except that no quantity reasonably disproportionate to any stated estimate or in absence of a stated estimate to any normal or otherwise comparable prior output or requirements may be tendered or demanded. iii. McMichael v. Price: P contracted to buy all the sand he could sell from D, but D refused to supply the sand because he said there was no mutuality; Court said the contract was binding on P because he was bound to buy all the sand he could sell from D and D was bound to supply all he required. d. Exclusive dealing 1. UCC §2-306(2)—make sure this really applies to Lucy(?): A lawful agreement by either the seller or the buyer for exclusive dealing in the kind of goods concerned imposes unless otherwise agreed an obligation by the seller to use best efforts to supply the goods and by the buyer to use best efforts to promote their sale. 2. Wood v. Lady Lucy McDuff: D contracted with P to exclusively market her endorsements and products in exchange for ½ profits. D said there was a lack of mutuality of obligation. Court implied that he would use his best efforts to market it. e. Satisfaction clauses i. When you’re not satisfied, you don’t have to do it. ii. The buyer is held to act in good faith subject to a reasonable man standard—if the report is satisfactory, he is bound. iii. Omni Group v. Seattle-First National Bank: D refused to sell property to P after deciding P had a free way out if they found the feasibility report unsatisfactory. Court said this was not true because the buyer would have to act reasonably in good faith. iv. If one party has complete discretion to avoid obligation, however, it won’t work. v. R §228: Satisfaction of the Obligor as a Condition 1. When it is a condition of an obligor’s duty that he be satisfied with respect to the obligee’s performance or with respect to something else, and it is practicable to determine whether a reasonable person in the position of the obligor would be satisfied, an interpretation is preferred under which the condition occurs if such a reasonable person in the position of the obligor would be satisfied. V. Moral obligation: Promise plus an antecedent benefit a. Antecedent benefit i. Mills v. Wyman: Son was sick and dad said he would pay P for caring for the son. No consideration because it was past (timing problem). Court ruled the promise was not enforceable. 1. If he had told him to continue taking care of his son in exchange for the money, it would have been okay 2. Moral obligation was not sufficient in this case a. Every promise creates a moral obligation and the court said it would not enforce every promise that didn’t have consideration and the law wants to protect people from their thoughtless promises ii. R §86: Promise for Benefit Received 1. (1) A promise made in recognition of a benefit previously received by the promisor from the promisee is binding to the extent necessary to prevent injustice. 2. (2) A promise is not binding under Subsection (1) a. (a) if the promisee conferred the benefit as a gift or for other reasons the promisor has not been unjustly enriched; or b. (b) to the extent that its value is disproportionate to the benefit. iii. Manwill v. Oyler: D was indebted to P for farm permit, but statute of limitations barred any action against it. D later gave an oral promise to pay but then refused. Court ruled that a moral obligation was generally not enough to enforce a contract. 1. R §82: Promise to Pay Indebtedness; Effect on the Statute of Limitations a. (1) A promise to pay all or part of an antecedent contractual or quasicontractual indebtedness owed by the promisor is binding if the indebtedness is still enforceable or would be except for the effect of a statute of limitations. b. (2) The following facts operate as such a promise unless other facts indicate a different intention: i. (a) A voluntary acknowledgement to the obligee, admitting the present existence of the antecedent indebtedness; or ii. (b) A voluntary transfer of money, a negotiable instrument, or other thing by the obligor to the obligee, made as interest on or part payment of or collateral security for the antecedent indebtedness; or iii. (c) A statement to the obligee that the statute of limitations will not be pleaded as a defense. 2. Bankrupt rule in the notes: If someone has a debt and goes bankrupt but makes a promise to pay the debt, the renewed contract will be enforceable. VI. Promissory Estoppel a. R §90: Promise Reasonably Inducing Action or Forbearance i. (1) A promise which the promisor should reasonably expect to induce action or forbearance on the part of the promisee or a third person and which does induce such action o forbearance is binding if injustice can be avoided only be enforcement of the promise. The remedy granted for breach may be limited as justice requires. b. Elements of PE i. There was a promise ii. Promise is one that the promisor would reasonably expect to induce action iii. Did the promise induce such action or forbearance iv. Promise is binding if injustice can be avoided only if enforced 1. Remedy limited as justice requires 2. Exceptions: binding without proof that the promise induced action or forbearance a. Charitable subscription i. Allegheny College: Mary pledged a charitable subscription to the school for $5,000 after her death in consideration of her interest in Christian Education (scholarship). After paying part, she repudiated. Court finds an implied acceptance and decides PE isn’t even necessary because there was consideration—a namesake. b. Marriage settlement c. When you don’t have consideration, PE is another route to take to argue you can get something out of the promise. i. Feinberg v. Peiffer: Woman relying on pension payments. Unlike Langer, there was no consideration, however she quit her job earlier than she would have and may have changed her financial plans according to the promise of money so she forbore from working and investing and was unjustly damaged. ii. Ricketts v. Scothorn: Grandfather gave granddaughter a promissory note telling her that she wouldn’t have to work so she quit her job, even though she was not required to. When he died the estate would not pay off the note. Court ruled it would be inequitable not to pay her. iii. Grouse v. Group Health: P accepted a job with GH, resigned from his current job, and was then told it had been given to someone else. This was an employment at will where both parties had a free way out—he didn’t have to show up, they could have fired him at any time. Court ruled D induced P to resign from his job and it was unjust because he had done so to his detriment. P had a right to assume he would be given a good faith opportunity to perform his job. VII. Remedies a. Three types of remedies: i. Restitution: Restores any benefit that P has conferred on D (Puts D in the position he was in before the contract—D back to zero 1. Refunds all money paid by P to D 2. “Disgorges D” ii. Reliance: Puts P in as good a position as he would have been in had the contract not been made—P back to zero 1. Restores to the promisee the costs incurred due to his reliance on the contract 2. Does not take into account promisee’s lost profit iii. Expectancy (compensatory): Puts P in as good a position as he would have been had the contract been performed—P from loss to gain 1. Standard measure of damages for breach of contract 2. Used with business contracts because it is easier to calculate damages b. R §344: Purposes of Remedies i. Judicial remedies under the rules stated in this Restatement serve to protect one or more of the following interests of a promisee: 1. (a) his “expectation interest,” which is his interest in having the benefit of his bargain by being put in as good a position as he would have been in had the contract been performed. 2. (b) his “reliance interest,” which is his interest in being reimbursed for loss caused by reliance on the contract by being put in as good a position as he would have been in had the contract not been made, or 3. (c) his “restitution interest,” which is his interest in having restored to him any benefit that he has conferred on the other party. c. Specific relief: i. Remedy where performance of the contract is ordered ii. Courts have a preference for monetary damages over specific relief. iii. Usually only granted if the subject matter of the contract is unique or monetary damages are inadequate (i.e. land) iv. UCC §2-716: Specific Performance; Buyer’s Right to Replevin 1. (1) Specific performance may be decreed where the goods are unique or in other proper circumstances. In a contract other than a consumer contract, specific performance may be decreed if the parties have agreed to that remedy. However, even if the parties agree to specific performance, specific performance may not be decreed if the breaching party’s sole remaining contractual obligation is payment of money. 2. (2) The decree of specific performance may include such terms and conditions as to payment of the price, damages, or other relief as the court may deem just. 3. (3) The buyer has a right of replevin or similar remedy for goods identified to the contract if after reasonable effort the buyer is unable to effect cover for such goods or the circumstances reasonably indicate that such effort will be unavailing or if the goods have been shipped under reservation and satisfaction of the security interest in them has been made or tendered. 4. (4) The buyer’s right under subsection (3) vests upon acquisition of a special property, even if the seller had not then repudiated or failed to deliver. VIII. Offers a. Reasonable person standard is the overall test in this area—if the reasonable person would think there was an offer or acceptance under the circumstances i. Lucy v. Zhemer: Where parties were drinking and joking about selling land, court upheld the contract because it reasonably appeared D was offering to sell his land. b. Fixed purpose test: Was the language used by the offeror intended as an expression of his fixed purpose to make an offer so that there was nothing left to do but accept—look at it from the offeree’s perspective and see if there as a reasonable impression created in his mind. i. R §24: Offer Defined 1. An offer is the manifestation of willingness to enter into a bargain, so made as to justify another person in understanding that his assent to that bargain is invited and will conclude it. ii. R §26: Preliminary Negotiations 1. A manifestation of willingness to enter into a bargain is not an offer if the person to whom it is addressed knows or has reason to know that the person making it does not intend to conclude a bargain until he has made a further manifestation of assent. a. Example: Advertisements are typically seen as being an invitation to offer (made to an indefinite number of people) c. Clear, definite, and explicit test: i. Lefkowitz v. Minneapolis Surplus: D put ads in paper offering specials on fur for $1 to the first to arrive on Saturday. P was first to show up but store refused to sell because the offer was for women according to house rules. Normally an ad is not an offer, but in this case it was clear and definite and so it could constitute an offer, acceptance of which would complete the contract. ii. Bait and switch technique: An (illegal) insincere offer in an ad to sell a product or service the advertiser does not intend or want to sell. Store puts ad in paper for great deal and when the customer shows up, they are “all out” and in turn push for a more expensive item’s purchase. d. Surrounding circumstances test: i. Southworth v. Oliver: D decided to sell land an inquired first with his neighbors to see if they were interested. P said he was. D left saying they would figure out the price and terms. P called D, offer still open. D sent P and three others a letter detailing the price and terms but then told D it was not an offer (he could just accept). Court listed four ways to determine if its an offer or an invitation to offer—don’t have to satisfy all four prongs; no words of promise but the terms were definite so there was an offer 1. What would a reasonable person believe? 2. What was the language used? a. Words of promise undertaking or commitment? (would be more likely to be an offer if so) 3. Was the offeree named or was it an indefinite group? 4. How definite is the proposal? There were no words of promise and there were four offerees, but the terms were definite so the court says there was an offer. e. UCC §2-207: Additional Terms in Acceptance or Confirmation i. (1) A definite and seasonable expression of acceptance or a written confirmation which is sent within a reasonable time operates as an acceptance even though it states terms additional to or different from those offered or agreed upon, unless acceptance is expressly made conditional on assent to the additional or different terms. ii. (2) The additional terms are to be construed as proposals for addition to the contract. Between merchants such terms become part of the contract unless: 1. (a) the offer expressly limits acceptance to the terms of the offer; 2. (b) they materially alter it; or 3. (c) notification of objection to them has already been given or is given within a reasonable time after notice of them is received. iii. (3) Conduct by both parties which recognizes the existence of a contract for sale although the writings of the parties do not otherwise establish a contract. In such cases the terms of the particular contract consist of those terms on which the writings of the parties agree, together with any supplementary terms incorporated under any provisions of this Act. f. Auctions: i. Normal auction: 1. Bidders are offering and the auctioneer is just inviting them to give offers. 2. The offer occurs when the buyer gives the highest bid. 3. The auction house can then accept or reject. a. Placing an item up for bid is not an offer but an invitation to offer. ii. Without-reserve auction: 1. Promise to sell item to whoever gives the highest bid. 2. The offer occurs at the notice of the auction with the condition that you are the highest bid. a. Example: Jackie O’s dresses will be sold to the highest bidder. The seller is obligated to the contract with the highest bidder. iii. Sharp-bids auction: Bid certain amount of money over the highest bid 1. This practice is condemned for public bidding and among private auctions 2. The offer occurs when the buyer says, “I bid X dollars over the highest bid.” 3. Defrauded parties can elect to void their offer. IX. Acceptance a. Mirror-image rule: The acceptance must follow the specific terms of the offer i. The offeror, as master of the offer, gives the power of acceptance to the offeree but can limit that power by controlling the method of acceptance. ii. For valid acceptance, the offer must be accepted in the way the offeror states. iii. La Sale Nat’l Bank v. Vega: Seller of put specific terms in the offer to sell: First, purchasing agent and seller must sign, then trustee must execute the agent. The first two signed, but the trustee never did, so no agreement. b. R §50: Acceptance of Offer Defined; Acceptance by Performance; Acceptance by Promise i. (1) Acceptance of an offer is a manifestation of assent to the terms thereof made by the offeree in a manner invited or required by the offer. ii. (2) Acceptance by performance requires that at least part of what the offer requests be performed or tendered and includes acceptance by a performance which operates as a return promise. iii. (3) Acceptance by promise requires that the offeree complete every act essential to the making of the promise. c. Restatement and UCC both say it is okay to accept it in a reasonable way if how to accept is not made explicit. i. R §30: Form of Acceptance Invited 1. (1) An offer may invite or require acceptance to be made by an affirmative answer in words, or by performing or refraining from performing a specified act, or may empower the offeree to make a selection of terms in his acceptance. 2. (2) Unless otherwise indicated by the language or the circumstances, an offer invites acceptance in any manner and by any medium reasonable in the circumstances. ii. UCC §2-206: Offer and Acceptance in Formation of Contract 1. (1) Unless otherwise unambiguously indicated by the language or circumstances a. (a) an offer to make a contract shall be construed as inviting acceptance in any manner and by any medium reasonable in the circumstances; b. (b) an order or other offer to buy goods for prompt or current shipment shall be construed as inviting acceptance either by a prompt promise to ship or by the prompt or current shipment of conforming or nonconforming goods, but the shipment of nonconforming goods is not an acceptance if the seller seasonably notifies the buyer that the shipment is offered only as an accommodation to the buyer. 2. (2) Where the beginning of a requested performance is a reasonable mode of acceptance an offeror that is not notified of acceptance within a reasonable time may treat the offer as having lapsed before acceptance. 3. (3) A definite and seasonable expression of acceptance in a record operates as an acceptance even if it contains terms additional to or different from the offer. iii. Hypo: Boone’s Farm receives a purchase order for 50 cases of apple wine at $6 per case, shipment made by 11/25, FOB truck. If acceptable, please telephone me immediately. 1. If you send acceptance by overnight express mail—depends on how literally you read the offer. Could say you have to call, but the offer doesn’t say that calling is the only method of acceptance. 2. UCC only requires acceptance by a reasonable medium and manner. d. Communication of the acceptance i. Must be done 1. Offeror can revoke if acceptance hasn’t been communicated 2. But, an offer cannot be withdrawn after it has been accepted. 3. Must exercise reasonable diligence to communicate it to offeror e. Performance as acceptance i. Evertite Roofing: D contracted with P for the re-roofing of D’s residence. The agreement was not binding until P signed or commenced performance of the work. P hired workers, loaded up truck and drove across the state, but found someone else doing the work once they got there. Court ruled P accepted by his preparation as performance (not the general rule?) and so D was bound. ii. R §36: Methods of Termination of the Power of Acceptance 1. (1) An offeree’s power of acceptance may be terminated by a. (a) rejection or counter-offer by the offeree, or b. (b) lapse of time, or c. (c) revocation by the offeror, or d. (d) death or incapacity of the offeror or offeree 2. (2) In addition, an offeree’s power of acceptance is terminated by the nonoccurrence of any condition of acceptance under the terms of the offer. f. Shipping non-conforming goods i. Can still be acceptance ii. Price quotes are generally not an offer, but an invitation to offer. iii. UCC §2-206(b): 1. an order or other offer to buy goods for prompt or current shipment shall be construed as inviting acceptance either by a prompt promise to ship or by the prompt or current shipment of conforming or nonconforming goods, but the shipment of nonconforming goods is not an acceptance if the seller seasonably notifies the buyer that the shipment is offered only as an accommodation to the buyer. iv. If the shipment is said to be an accommodation, it is a counter-offer and not acceptance v. Corinthian Pharmaceutical: Corinthian found out about Lederle’s impending price increase and ordered 1,000 vials at the current price. L shipped 50 vials at that price as an exception to its general rule and said the remainder would arrive at the new price. If Lederle had said nothing, the shipment would have been acceptance. But, the court inferred it as an accommodation because of their statement. g. Rewards i. Rewards are offers that can be accepted by anyone to perform—Performance of the condition dispenses of the need for notice of acceptance ii. R §54: Acceptance by Performance; Necessity of Notification to the Offeror a. (2) If an offeree who accepts by rendering a performance has reason to know that the offeror has no adequate means of learning of the performance with reasonable promptness and certainty, the contractual duty of the offeror is discharged unless… b. (c) the offer indicates that notification of acceptance is not required. iii. Carbolic Smoke Ball: D put an ad in paper promising 100 pounds to anyone who used CSB three times daily and then contracted influenza. P used ball as directed and got sick, but D would not pay because it was never notified of her acceptance. Court ruled that she had accepted by performance. h. Knowledge of existence of offer i. There can be no acceptance unless you know the offer is there 1. Doesn’t matter if you know about the offer but have to be forced to give the info 2. If a police officer gives info, you can argue pre-existing duty 3. Policy reason: People with valuable information might wait and see if there is a reward first before disclosing information. ii. Glover v. Jewish War Veterans: D offered reward in the paper for information leading to the arrest of murderer. Not knowing of the offer, P gave info to police that lead them to suspect. P later learned of reward and wanted to claim it, but court ruled she could not have accepted the offer without knowing of its existence. iii. Industrial America: Bush Hog informed several brokers, including P, that they wanted a merger. P got lead about Fulton wanting to merge as well. D had an ad in the paper seeking candidates, ending “brokers fully protected.” P set up a meeting between D and BH, but the two companies went behind his back and made an agreement. Court ruled that P knew of the offer, accepted by performance, and so there was a contract. i. Acceptance by promise, performance, or either i. R §32: Invitation of Promise or Performance 1. In case of doubt an offer is interpreted as inviting the offeree to accept either by promising to perform what the offer requests or by rendering the performance, as the offeree chooses. ii. R §30: Form of Acceptance Invited 1. (1) An offer may invite or require acceptance to be made by an affirmative answer in words, or by performing or refraining from performing a specified act, or may empower the offeree to make a selection of terms in his acceptance. 2. (2) Unless otherwise indicated by the language or the circumstances, an offer invites acceptance in any manner and by any medium reasonable in the circumstances. a. Hypo: Reagan tells Gorbie “If you tear down this wall, I will make Vodka the national drink of US.” This is ambiguous, Gorbie can choose acceptance by tearing down the wall or promising to tear down the wall. iii. R §53: Acceptance by Performance; Manifestation of Intention Not to Accept 1. (1) An offer can be accepted by the rendering of a performance only if the offer invites such an acceptance. 2. (2) Except as stated in §69, the rendering of a performance does not constitute an acceptance if within a reasonable time the offeree exercises reasonable diligence to notify the offeror of non-acceptance. 3. (3) Where an offer of a promise invites acceptance by performance and does not invite a promissory acceptance, the rendering of the invited performance does not constitute an acceptance if before the offeror performs his promise the offeree manifests an intention not to accept. a. Hypo: Dupre says that if you blink your eyes you accept her offer. If you say that by blinking, you are not accepting, then you are not bound to her offer. iv. R §56: Acceptance by Promise; Necessity of Notification to Offeror 1. Except as states in §69 or where the offer manifests a contrary intention, it is essential to an acceptance by promise either that the offeree exercise reasonable diligence to notify the offeror of acceptance or that the offeror receive the acceptance seasonably. a. Hypo: If Gorbie tells his aids, “I accept Reagan’s offer,” he has not accepted until he notifies Reagan. v. R §45: Option Contract Created by Part Performance or Tender 1. (1) Where an offer invites an offeree to accept by rendering a performance and does not invite a promissory acceptance, an option contract is created when the offeree tenders or begins the invited performance or tenders a beginning of it. 2. (2) The offeror’s duty of performance under any option contract so created is conditional on completion or tender of the invited performance in accordance with the terms of the offer. a. Hypo: Reagan says, “When and only when you tear down this wall, I will make Vodka the national drink.” Asks for performance only, so when Gorbie if he says, “I promise to tear it down,” there is no acceptance. However, when Gorbie takes down part of the wall, Reagan can no longer revoke his offer. There is NO contract until Gorbie tears the wall all the way down, it just means that the offer has to stay open. vi. R §54: Acceptance by Performance: Necessity of Notification to Offeror 1. (1) Where an offer invites an offeree to accept by rendering a performance, no notification is necessary to make such an acceptance effective unless the offer requests such a notification. 2. (2) If an offeree who accepts by rendering a performance has reason to know that the offeror has no adequate means of learning of the performance with reasonable promptness and certainty, the contractual duty of the offeror is discharged unless a. (a) the offeree expresses reasonable diligence to notify the offeror of acceptance, or b. (b) the offeror learns of the performance within a reasonable time, or c. (c) the offer indicates that notification of acceptance is not required. i. Hypo: Gorbie doesn’t need to tell Reagan he is tearing down the wall, he just needs to do it to accept. vii. R §62: Effect of Performance by Offeree Where Offer Invites Either Performance or Promise 1. (1) Where an offer invites an offeree to choose between acceptance by promise and acceptance by performance, the tender or beginning of the invited performance or a tender of a beginning of it is an acceptance by performance. 2. (2) Such an acceptance operates as a promise to render complete performance. a. Hypo: If Reagan has not been specific as to acceptance by promise or performance and Gorbie tears down some of the wall, Reagan cannot then revoke. Gorbie has accepted and made a promise to render complete performance. j. Mailbox rule: Once acceptance has been placed in the mail, the offer has been accepted. i. Offeror can override this rule by saying it has to be received to be accepted when making the offer—remember, he is master of the offer. ii. Does this apply to email? Factors to consider: 1. Can you unsend email? 2. Filters can hold it up 3. If the rule is about it leaving your control (putting it in the mailbox), then is it the same with email? iii. R §40: Time When Rejection or Counter-Offer Terminates the Power of Acceptance 1. Rejection or counter-offer by mail or telegram does not terminate the power of acceptance until received by the offeror, but limits the power so that a letter or telegram of acceptance started after the sending of an otherwise effective rejection or counter-offer is only a counter-offer unless the acceptance is received by the offeror before he receives the rejection or counter-offer. 2. Basically means… a. Offeree sends rejection first, then acceptance: Mailbox rule goes away, whatever the offeror receives first is binding. b. Offeree sends acceptance first, then rejection, acceptance gets there first: Mailbox rule applies and there is a contract. c. Offeree sends acceptance first, then rejection, rejection gets there first: Split of authority. One side says there is no contract because offeror thinks you’ve rejected it. The other says that the mailbox rule applies to the acceptance, but there is an exception for when the offeror has relied on it. k. Acceptance by silence i. R §69: Acceptance by Silence or Exercise of Dominion 1. (1) Where an offeree fails to reply to an offer, his silence and inaction operate as an acceptance in the following cases only: a. (a) Where an offeree takes the benefit of offered services with reasonable opportunity to reject them and reason to know that they were offered with the expectation of compensation. b. (b) Where an offeror has stated or given the offeree reason to understand that assent may be manifested by silence or inaction, and the offeree in remaining silent and inactive intends to accept the offer. c. (c) Where because of previous dealings or otherwise, it is reasonable that the offeree should notify the offeror if he does not intend to accept. 2. (2) An offeree who does any act inconsistent with the offeror’s ownership of offered property is bound in accordance with the offered terms unless they are manifestly unreasonable. But if the act is wrongful as against the offeror it is an acceptance only if ratified by him. ii. Hypo: Suppose Bailey has Bascom’s Folley and West writes and says, “I will sell you the horse for $700. If I don’t hear from you by next week, I’ll know you accept.” Farmer does not reply and does not intend to accept. 1. Not (c) because no previous dealings 2. Not (b) as offeree does not intend to accept 3. Could argue that Bailey enjoys the benefit of having/riding his horse iii. Ammons v. Wilson: D’s salesman booked two orders from P for shortening. Normally these bookings were accepted and shipped to P within one week. This time, P heard nothing from D for almost two weeks and when he called to inquire, he was told the offers were declined. Court ruled D’s silence could operate as acceptance because of previous dealings. iv. Exercise of Dominion: 1. Involves taking the benefit of offered services 2. Where an offeree exercises dominion over things which are offered to him, such exercise of dominion in the absence of other circumstances showing a contrary intention is acceptance. a. But, if the exercise of dominion is tortious, the offeror may treat is an acceptance eve if the offeree manifests an intent not to be bound. 3. Russell v. Texas: D made use of P’s surface to mine oil and gas from P’s land and on other’s land (which D had mining rights over). P attempted to create a contract to reimburse for the surface use, and said acceptance would be indicated by continued use of the land. Court applied the rule that an offeree’s silence and inaction can operate as an acceptance where the offeree takes the benefit of offered services with reasonable opportunity to reject them and with reason to know that they were offered with the expectation of compensation. v. Hammond v.Yarn: Looked to previous dealings to see if there as acceptance. vi. Unsolicited goods: State laws often give people the right to refuse to accept unsolicited goods and say that they are not bound to return them. 1. Federal Trade Commission: The mailing of unordered merchandise or communications constitutes unfair trade practice. Such merchandise may be treated as a gift by the recipient. X. Termination of Offer a. Revocation i. R §42: Revocation by Communication From Offeror Received by Offeree 1. An offeree’s power of acceptance is terminated when the offeree receives from the offeror a manifestation of an intention not to enter into the proposed contract. ii. R §43: Indirect Communication of Revocation 1. An offeree’s power of acceptance is terminated when the offeror takes definite action inconsistent with an intention to enter into the proposed contract and the offeree acquires reliable information to that effect. iii. Dickenson v. Dodds: Dodds wrote P agreeing to sell estate, and that P had until Friday decide. Thursday P decided to accept, but before notifying D he heard that D was planned to sell to another. P sent message of acceptance to D’s residence that night and tried to accept in person on Friday morning, but it was too late, D had already sold estate. Court held that agreeing to sell the property to a third party was a revocation of Dodds’s offer to Dickinson. b. Power of Acceptance i. R §36: Methods of Termination of the Power of Acceptance 1. (1) An offeree’s power of acceptance may be terminated by a. (a) rejection or counter-offer by the offeree, or b. (b) lapse of time, or c. (c) revocation by the offeror, or d. (d) death or incapacity of the offeror or offeree. 2. (2) In addition, an offeree’s power of acceptance is terminated by the nonoccurrence of any condition of acceptance under the terms of the offer. c. R §45: Option Contract Created by Part Performance or Tender i. (1) Where an offer invites an offeree to accept by rendering a performance and does not invite a promissory acceptance, an option contract is created when the offeree tenders or begins the invited performance or tenders a beginning of it. 1. Basically, notice of revocation has to be equal to the communication in giving the offer. d. Mailbox rule applies only to acceptance and NOT revocation. Revocation is valid only on receipt. XI. Irrevocable Offer a. Option contract: Mini-me, or a little contract with a big punch i. Two ways to create an option contract 1. A promise of performance 2. Consideration for a promise a. Nominal consideration is okay (some courts don’t even require that it be paid) ii. Not terminated by counter-offer, rejection, death or incapacity 1. Exception: If the optionee rejected the offer within the option time, and the optioner relied on that rejection, the optionee may not be able to then accept before the close of the option period. 2. R §37: Termination of Power of Acceptance Under Option Contract a. Notwithstanding §§38-49, the power of acceptance under an option contract is not terminated by rejection or counter-offer, by revocation, or by death or incapacity of the offeror, unless the requirements are met for the discharge of a contractual duty. iii. Unlike normal offers, a conditional acceptance does not revoke the offer. iv. Additional terms have no effect on the offer. v. For non-merchants, a contract is binding if it is in writing, signed by offeror, and recites a purported consideration (doesn’t have to be actually given) b. UCC §2-205: Firm Offers i. An offer by a merchant to buy or sell goods in a signed writing which by its terms gives assurance that it will be held open is not revocable, for lack of consideration, during the time stated or if no time is stated for a reasonable time, but in no event may such period of irrevocability exceed three months; but any such terms of assurance on a form supplied by the offeree must be separately signed by the offeror. 1. Basically, if you are a merchant and it involves goods, it must be in a signed writing, the time can’t succeed three months, but you don’t need consideration. c. R §87: Option Contract i. (1) An offer is binding as an option contract if it 1. (a) is in writing and signed by the offeror, recites a purported consideration for the making of the offer, and proposes an exchange on fair terms within a reasonable time; or 2. (b) is made irrevocable by statute. ii. (2) An offer which the offeror should reasonably expect to induce action or forbearance of a substantial character on the part of the offeree before acceptance and which does induce such action or forbearance is binding as an option contract to the extent necessary to avoid injustice. d. Subcontractors and general contractors i. Process: Prime contractor asks the subs to give him a bid to know how much he needs to bid on the big job. 1. Subcontractors give prime an offer 2. Based on all the sub’s offers, prime puts a bid (offer) in to the government. a. Two offers: i. Sub’s offer to the prime ii. Prime’s offer to the government 3. Government accepts prime’s offer, so prime is obligated to government to complete work under a certain amount. 4. Prime then accepts sub’s offer. ii. The prime contractor can still shop around for other subcontractors even if after the government has awarded him the job. He has NOT accepted the subcontractor’s offer when he bids to the government. 1. What the prime contractor should do is make an option contract just so the sub keeps his bid open long enough for him to make a bid to the government. 2. The sub may be held to its bid anyhow if the prime has relied on it (see R §45). XII. Indefinite Agreements a. As a general rule, no contract exists unless the terms are certain and explicit. b. R §33: Certainty i. (1) Even though a manifestation of intention is intended to be understood as an offer, it cannot be accepted so as to form a contract unless the terms of the contract are reasonably certain. ii. (2) The terms of a contract are reasonably certain if they provide a basis for determining the existence of a breach and for giving an appropriate remedy. iii. (3) The fact that one or more terms of a proposed bargain are left open or uncertain may show that a manifestation of intention is not intended to be understood as an offer or as an acceptance. c. Quantum Meruit: “As much as deserved” i. If one party has performed in reliance of the terms in an indefinite agreement, the law will presume a promise to pay the reasonable value of the services rendered. ii. Determined by what comparable employees are paid and multiply salary times hours. d. Varney v. Ditmars: D employer asked P employee to stay with him and get him out of the trouble he was having and on the first of next year he would give P a “fair share of his profits.” The court rules that if the promise was for goods or chattels, the fair market value of those could be determined and the promise could be enforced. But “fair share of profits” was held to be too difficult to ascertain. Cardozo, dissenting, said that they could have used industry practices to determine what percentage of profits a typical bonus would be. XIII. Incomplete or Deferred Agreement a. When elements of the contract are left open for negotiation i. R §230: “Where the parties have completed their negotiations of what they regard as essential elements, and performance has begun on the good faith understanding that agreement on the unsettled matters will follow, the court will find and enforce a contract , even though the parties have expressly left these other elements for future negotiation and agreement, if some objective method of determination is available, independent of either party’s mere wish or desire. Such objective criteria may be found in the agreement itself, commercial practice or other usage or custom. If the contract can be rendered certain and complete, by reference to something certain, the court will fill in the gaps.” ii. MGM v. Scheider: D filmed a pilot for P and was supposed to continue filming the TV series when he back out of the contract. All elements of the contract were complete except the start of the filming date. Court ruled that custom and practice in the industry make the approximate start date clear, so the contract was enforced. b. UCC §2-204(3): Formation in General i. …(3) Even though one or more terms are left open a contract for sale does not fail for indefiniteness if the parties have intended to make a contract and there is a reasonably certain basis for giving an appropriate remedy. c. UCC §2-305: Open Price Term i. (1) The parties if they so intend can conclude a contract for sale even though the price is not settled. In such a case the price is a reasonable price at the time for delivery if 1. (a) nothing is said as to price; or 2. (b) the price is left to be agreed by the parties and they fail to agree; or 3. (c) the price is to be fixed in terms of some agreed market or other standard as set or recorded by a third person or agency and it is not so set or recorded. ii. (2) A price to be fixed by the seller or by the buyer means a price to be fixed in good faith. iii. (3) When a price left to be fixed otherwise than by agreement of the parties fails to be fixed through fault of one party the other may at the party’s option treat the contract as canceled or the party may fix a reasonable price. iv. (4) Where, however, the parties intend not to be bound unless the price be fixed or agreed and it is not fixed or agreed there is no contract. In such a case the buyer must return any goods already received or if unable so to do must pay their reasonable value at the time of delivery and the seller must return any portion of the price paid on account.