View the supporting material

advertisement

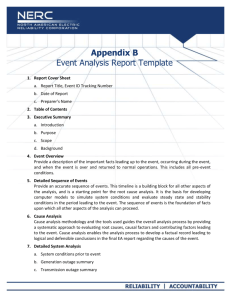

Paresh Dawda ASSESSMENT OF FEBRILE CHILDREN Please note this improvement project was submitted for the Advanced Improvement in Quality and Safety programme by the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement Page | 0 Paresh Dawda Table of Contents List of figures: ....................................................................................................... 1 Abbreviations ........................................................................................................ 2 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 3 Context of Practice................................................................................................ 3 Sustainability ......................................................................................................... 4 Quality Improvement Tools ................................................................................... 6 Results ................................................................................................................ 13 Conclusions ........................................................................................................ 15 Appendices ......................................................................................................... 18 Appendix 1 – Project Plan ............................................................................... 18 Appendix 2 - The practice as a system ............................................................ 19 Appendix 3 – Driver Diagram for Patient Care Process ................................... 20 Appendix 4 – Process Map .............................................................................. 21 Appendix 5 – Sustainability Analysis ............................................................... 23 Appendix 6 – Results of Surveys ..................................................................... 24 Appendix 7 – Log of a selection of PDSA Cycles ............................................ 28 Appendix 8 – FMEA ......................................................................................... 40 Appendix 9 – Measurement ............................................................................. 41 References ......................................................................................................... 43 Page | 1 Page | 2 List of figures: Figure 1: Impact of 5S Intervention .................................................................... 30 Figure 2: 5S table top visual management card ................................................. 31 Figure 3: 5S visual management card + equipment ........................................... 31 Figure 4: Tympanic thermometer with memory prompt ...................................... 33 Figure 5: Digital thermometer with memory prompt ........................................... 33 Figure 6: Mouse mat .......................................................................................... 35 Figure 7: Mouse mat enlarged ........................................................................... 35 Figure 8: Screenshot of intranet with traffic light system reference .................... 35 Figure 9: Screenshot of data recording template ............................................... 37 Figure 10: Diagram of algorithm for redundancy check with screen shot of prompt ...................................................................................................................... 39 Figure 11: Run chart of % of febrile children with all four components completed ................................................................................................................................. 41 Figure 12: : Pareto analysis - baseline data ...................................................... 41 Figure 13: Number of measurements for each patient ....................................... 41 Figure 14: Balancing measure ........................................................................... 41 Page | 1 Paresh Dawda Abbreviations AIQS CRT EFQM FMEA GP HCA NICE PDSA PR RR UAT Advanced Improvement in Quality and Safety Capillary refill time European Foundation for Quality Management failure modes and effects analysis General Medical Practitioner Healthcare Assistant National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Plan, Do, Study, Act cycle Pulse Rate Respiratory rate Urgent Access Team Page | 2 Introduction The translation of evidence into practice has been a challenge for all healthcare organisations. The reliability of providing patients with known evidence based interventions in healthcare is poor and occurs just over half of the time (McGlynn et al. 2003). The first step in translating research into practice is to summarise the evidence (Pronovost et al. 2008). In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) reviews and makes recommendations on standards of care. In general practice children presenting with an acute febrile illness is a common reason for consultation. The prevalence of serious illness is low (Van den Bruel et al. 2007), however, more than half of the children with a serious febrile illness are not identified at first presentation (M. J. Thompson et al. 2006). A recent review of childhood mortality with primary care involvement identified 27% of deaths were attributed to acute infections (Harnden et al. 2009). GPs have a challenging task to identify those children with a serious illness from a large number of children who will have minor illnesses that are often self-limiting. NICE have published guidance on the assessment and management of children with febrile illness (NICE 2007). The aim of this project was to ensure that in the GP practice 95% of children under the age of 5 presenting with a febrile illness were assessed in accordance with NICE guidelines by October 2011. Context of Practice Page | 3 This project was conducted at a large teaching General Practice in East Hertfordshire. The surgery has a registered list size of 20,000 patients, and employs over 50 staff, which includes a number of learners from multiple disciplines. The practice has been on an organisational development programme since 2006. This development programme has seen the practice restructure itself as a 'system' as shown in Appendix 2 - The practice as a system. As a result of this organisational development journey, the practice is increasingly aligned with quality improvement approaches such as Lean and Six Sigma and indeed achieved the European Foundation for Quality Management's (EFQM) Committed to Excellence Award in 2008 in recognition. Hence, a drive for excellence is increasingly embedded into the culture of the organisation, and in some respects reduces the impact of potential barriers in the context of this improvement project. However, the practice is still relatively early in its journey. The experience of quality improvement approaches has been with administrative processes that support provision of clinical care rather than clinical care processes. Indeed, a review of past projects directly related to clinical care demonstrates the standard approach used has been clinical audit. Many of the previous interventions to improve the quality of clinical care relied on a combination of hard work, vigilance, clinical guidelines, education and training. These are all necessary improvement concepts. They are, however, all concepts know to deliver less than 80% reliability (Resar 2006). Furthermore, the outcomes from previous audits have not been sustained. It was essential that this project therefore demonstrated innovation and interventions consistent with providing more reliable and sustainable solutions. Sustainability Page | 4 The evidence suggests that very few improvement projects are sustained in the long run with some suggesting up to 70% of improvement projects are not sustained (Anon 2009). Reasons often cited for this are employee resistance to change, management behaviour not supporting the change and inadequate resources. This project therefore needed to overcome those obstacles. Furthermore, in the context of general practice there is a great deal of overlap between management and partnership behaviour as many partners will assume aspects of the management function. This was particularly significant in this practice which has 12 partners. An attribute of sustainable projects is alignment with the practice’s aim, mission, vision and philosophy or the ‘strategic fit’. This project was predominantly in the “patient care process" of the system. The mission of the patient care process is to "provide evidence-based patient centred care treating the person in a safe and compassionate manner". The driver diagram (Appendix 3 – Driver Diagram for Patient Care Process) visual illustrates how this project aligns with the mission of the patient care process and how that then aligns with the mission of the organisation in "delivering excellence in healthcare." The swim lane process map (Appendix 4 – Process Map), however, also illustrates that this project does also impact another process of "recording and monitoring" in the system. Attributes of sustainable project may be categorised into process, staff and organisation. The sustainability model (Maher et al. 2010) provides a structured framework for assessing a project against the various components that are known to positively correlate with a more sustainable project. An analysis of this project against those components is illustrated by the radar chart in Appendix 5 – Sustainability Analysis. Page | 5 This tool is ideally administered at several stages of the project, including at the beginning, at mid-points, and finally at the end. Furthermore, it is ideally rated against the components by others in the improvement team. However, I became aware of this tool after I had started the improvement project, and as it was the first time I was utilising this tool, I rated it myself and only at the point I became aware of it. It provided a really useful insight into areas to explore to increase the probability of having a more sustainable project. In future projects I will leverage the utility of this tool further by using it at several points in the lifecycle of the project. A review of the sustainability analysis confirmed the alignment discussed above which scored highly. Areas where there were significant gaps included the criteria of “benefits beyond helping patients” and “staff behaviours towards the change”. These insights were particularly helpful in understanding the planning of the project to include aspects that would reinforce and maximise the engagement of staff and reduce resistance to change. Quality Improvement Tools A structured and systematic approach to improvement utilises a data driven informed approach to change where each of the solutions are selected and identified on the basis of a diagnosis phase. The solutions are tested and refined in the real world and when shown to be effective implemented. The approaches used in this project include a series of tools known to help engagement thereby trying to embed the change into routine practice (Wilcock et al. 2003; Hawkins & Lindsay 2006; Baker 2000; Beckman & Frankel 1984; Institute for Healthcare Improvement 2004; Pronovost et al. 2008; Langley et al. 2009). These include: Page | 6 use of patient stories use of data involvement of staff in the diagnosis, through leadership walk arounds, staff surveys and observations involvement of as wide a range of people as possible in testing and trying out ideas and PDSA use of regular communication on progress of the project through updates and reports which were programmed in the project plan (Appendix 1 – Project Plan). A personal reflection on the use of these tools was on the whole extremely positive. Particularly, the use of the staff survey in the 'diagnostics' was invaluable and this is supported by comments such as "until i started to look at this as an improvement project I was not that aware of the guidance” and “interested to find out how you are going to use the survey -great idea! Made me read the guidelines and ?change practice". The use of patient stories did not have as much impact as suggested in the literature (Wilcock et al. 2003; Hawkins & Lindsay 2006) and from anecdotal evidence of others that have used it. Perhaps, one of the reasons for this is because the attitude of the clinicians towards the project was very favourable (Appendix 6 – Results of Surveys), where in response to the question “How relevant do you think the following measures are in the assessment of febrile children and how often do you measure them?” everyone rated it as either "strongly agree" or "tend to agree". This hypothesis is further supported by strong correlation with the criteria in the sustainability assessment on “clinical leadership engagement and support”. This was unexpected and is in contrast with published literature (M. Thompson et al. 2008). Page | 7 The use of data was particularly powerful in combination with both the leadership walk rounds where the approach was a combination of an appreciative enquiry and round of influence (Reinertsen & Johnson 2010). NICE guidance on assessment of febrile children recommends all febrile children under the age of five have their temperature, pulse rate, respiratory rate and capillary refill time measured (NICE, 2007). The baseline data showed that ALL four aspects of the assessment of febrile children were never done (Appendix 9 – Measurement). During leadership walk rounds some staff often demonstrated their awareness of the guidance and stated that they always measure the four components. The baseline data was powerful in that it provided an objective non-judgmental challenge, that subsequently led on to an appreciation that non-conformance with the guidance was a routine violation. A further benefit of involving staff in the diagnosis was it helped provide education, and offered an opportunity for staff to make suggestions, and indeed a number of those suggestions were actually tested as ideas for change (Appendix 7 – Log of a selection of PDSA Cycles). This was a direct result of recognising the need to improve staff behaviours identified through the sustainability analysis. A criticism of guidelines such as those produced by NICE is that recommendations made are not directly related to behaviours (Michie & Johnston 2004). Hence asking a number of different members of the team to conduct and test ideas for change helped to translate the recommendations into change behaviours. These included other doctors, nurses, and healthcare assistants. The use of PDSA and involving staff in testing is said to offer a number of advantages by demonstrating whether change ideas may work in the real world or not, refine change ideas and enhancing engagement, through providing opportunities for others to be involved in change project. This correlates well with human motivational theory that suggests human Page | 8 motivation is influenced by autonomy, mastery and sense of purpose (Pink 2009). The use of driver diagram (Appendix 3 – Driver Diagram for Patient Care Process) provides the purpose and the use of PDSA provides a sense of autonomy and mastery. Regular communication throughout the scope of the project was through use of email and intranet, as well as personal opportunistic face to face communication. This strategy proved enormously successful in maintaining the will of others but moreover gave the opportunity to seek feedback and further ideas for change. The staff survey and leadership walk arounds identified a need for education and training. This was provided by an online learning tool, hosted on the practice's intranet and then further signposting to an online tool offered by BMJ learning in association with NICE. The literature on reliability in healthcare identifies two sets of change concepts. The first set that includes training and education, reliance on hard work, vigilance, personal checklists etc is provides the opportunity to achieve reliability unto 80% (Resar 2006; IHI 2007). A second group of change concepts however raises the bar and provides the opportunity for a reliability of 95%. These change concepts include process standardisation, a focus on human factors and the redundancy checks. In this project, in order to achieve the 95% reliability standard set, it was imperative that change concepts from both groups were tested and implemented if successful. The literature on human error confirms the inevitability of human error, particularly when weaker aspects of cognition such as short term memory are relied upon (J. T. Reason 1990; J. Reason 2000; HSE n.d.). Another cause of 'care delivery problems' is violations or deliberate deviation from policy and protocol (Amalberti et al. 2006). Page | 9 The reasons for violations are varied and include perception of productivity and efficiency gain, as well as attitudes towards perceived risk and harm from noncompliance that is often reinforced by the resilience of biology. The accident causation model (Charles Vincent et al. 1998) suggests that to reduce the risk of care delivery problems, one may look at a range of error producing conditions that include a range of factors that includes a review of the task and then environmental factors. The insights from observation were confirmed from direct questioning on the staff survey. These showed that often the omission arose as a result of absent equipment, a failure to remember to check all four components, a lack of confidence in interpretation or failure to record the assessment. Leadership walkarounds also confirmed that violations took place. That is staff admitted to not always checking, for example, the pulse rate, and reasons they cites included a sense that the child did not look unwell or that it was time consuming and felt to be unnecessary. In keeping with the philosophy of "make it easier to the right thing and harder to do the wrong thing" a series of human factors interventions were tested and implemented (Appendix 7 – Log of a selection of PDSA Cycles). The first aspect of the change was to ensure equipment was easily available. In other quality improvement projects the ease of availability of equipment has been an issue (Pronovost et al. 2008). The organisation of the workplace and environment using the ‘5S’ lean tool (Amnis 2011) offers a solution to this problem. Through a series of iterative cycles the tool was tested and subsequently implemented (Figure 3: 5S visual management card + equipment). Measurement of equipment availability showed that it was more consistently available after implementation of 5S (Figure 1: Impact of 5S Intervention). A further benefit of this tool was that it that its approach is being considered for wider use in the consulting room. Page | 10 A key change concept associated with high reliability is the suggestion of linking interventions with existing habits. A Pareto analysis of the baseline data (Figure 12, page 41) showed that of the four components in the ‘bundle’ the temperature was being measured just over 80% of the time. This was confirmed again during observation. Observing the task also showed that the temperature was checked using a tympanic thermometer, which required the value of the temperature to be read on a digital LCD display. A memory prompt sticker was tested and placed just underneath the LCD display as a symbolic barrier to prevent clinicians forgetting to check the other aspects of the assessment (Figure 4 and Figure 5, page 33). The purpose of the assessments is to use a risk based approach to identify children with possible underlying serious illness. The staff survey (Appendix 6 – Results of Surveys) showed a wide variation of clinician’s confidence in interpreting the measurements from the assessment and specific free text comments in the survey suggesting better compliance “if a card / sheet in rooms” was available and therefore “making it easier to refer to”. PDSA cycles were used to test the potential solutions. The final solution was informed by the observation of the task and qualitative feedback. This identified that reminder cards on noticeboards, or on desk would very quickly become misplaced. The common aspect in the task in every room was the use of the computer and mouse. Hence, the normal values were placed on a mouse mat (Figure 7: Mouse mat enlarged) specifically designed with a picture of a little girl having her temperature checked to further provide a memory prompt, to check the temperature, as well as serving the need to have easily accessible normal values. Supplementary information was place on the front page of the practice intranet, as well hyperlinks to relevant menus and identified in the search engine for ease of reference (Figure 8: Screenshot of intranet with traffic light system reference). Page | 11 A further human factors issue again identified from the survey was a series of prompts to make the data recording easier so once values are measured it is easier for clinicians to record them. An advantage of computerised records is that it offers the potential for IT solutions. A template was created with fields for the four parameters and also a field to assess the outcome of traffic light assessment (Figure 9: Screenshot of data recording template). This template was inserted into a further template commonly used for recording of ‘acute respiratory infections’. Hence, a series of interventions in keeping with the principle “make it easier to the right thing and harder to do the wrong thing” were tested. A criticism of this approach is that there were multiple interventions being made and the model for improvement approach recommends that each change is tested and refined, and the outcome measured before making further changes. This implies that the changes should be sequential in nature. However, the accelerated model for improvement suggests that more rapid change may be achieved through parallel use of multiple PDSA cycles (Langley et al. 2009). This was the experience in this project where the approach of parallel PDSA cycles actually enabled it to be completed earlier than scheduled. Moreover, by involving a great number of people in testing of the PDSA cycles, there was an anecdotal sense of greater engagement. A final principle of reliable design recognises that despite a range of interventions there will still be a failure leading to a care delivery problem. Therefore interventions to “spot and stop” the failure, before it causes harm to patients, are required. The use of a standardised recording template facilitated an automated solution for the redundancy check (IHI 2007). The clinical system offers the facility for an electronic algorithm to be programmed that can be activated by a read code trigger. The Page | 12 algorithm (Figure 10: Diagram of algorithm for redundancy check with screen shot of prompt) was programmed into the clinical system and tested using a series of test patients and refined until it functioned as expected. The algorithm was triggered on the basis of Read codes entered as a problem title in the electronic medical records. On conducting a FMEA of this intervention it became apparent that there were several points at which the intervention may fail (Appendix 8 – FMEA). In order to mitigate these failures an analysis of the read code usage for children presenting with a fever was undertaken on a daily basis (as the data for the output metric was being collated). These read codes were then linked to the algorithm. If the data had not been recorded a prompt would appear forcing the clinician to enter the data or actively quit from the algorithm. Hence, the only other failure mode that remained was if the clinician did not enter any read code. To mitigate against this a further intervention was designed. This was a personalised feedback. The feedback would be given in writing on a postcard. The front of the postcard was designed to have the picture of the same girl having her temperature taken together with the normal values and the traffic light system. Results A series of interventions were used in parallel. Each one of these interventions was tested and assessed individually using a combination of subjective and objective measures as detailed in Appendix 7 – Log of a selection of PDSA Cycles. The aim was to have 95% of febrile children under the age of five assessed using all four parameters recommended by NICE. The measurement strategy was to use daily measures and express it as a percentage (Figure 11, page 41). This shows that the percentage of children assessed using all four parameters started to improve but the Page | 13 process had not become stable yet. However, the denominator was small and hence only one or two patients would significantly alter the percentage and cause wide swings. This was a disadvantage in retrospect of having a small denominator and using a daily measurement. However, a big advantage of having daily measurements was to provide a large number of data points and therefore provide a good understanding of the variation using statistical process control. In order to better understand the variation a second process control chart was used for each consecutive patient thereby giving many more data points. Each patient was assigned a score of 1,2,3 or 4 based on the number of items recommended by NICE that were measured. Analysis using this methodology (Figure 13, page 41) provides greater clarity of the improvement achieved. It is recommended that improvement projects have measures that include outcome measures, process measures and balancing measures (Clarke et al. 2010). The purpose of this project was to ensure the assessments were conducted as per national guidance. This is the output being sought and whilst not an direct outcome measure, it may be considered as a proxy outcome measure. Ideally, the outcome measure would include percentage of children with serious illness identified at first presentation. However, the low prevalence of serious illness in primary care makes this a difficult measure over a short period of time. A possibility is to use a trigger tool methodology to identify omissions causing harm, however, there is no such validated tool. A concern was that requiring clinicians to do the assessment in all febrile children would lead to longer consultations and during the walk around it was identified that this was one of the reasons for the violation of not measuring all four aspects. Hence, a balancing measure of consultation length was used. This showed no change in the consultation time following the improvements (Figure 14: Balancing measure). Page | 14 Conclusions The purpose of this project was to improve quality of care by implementing guidelines produced by NICE. The project used a series of quality improvement tools designed to provide a structured approach to the improvement and maximise the opportunities to make the changes sustainable. The improvements were in the context of an organisation well versed with change management approaches. A key learning for the organisation was the benefit of embracing the human factors elements of the improvement project. These human factors e.g. 5S approach, elements have provided the opportunity to spread generic solutions to improve care and productivity generally. The project was also carried in the context of an educational programme, AIQS. The active personal engagement in the programme, through the philosophy and actions outline in the learning agreement served to enrich and embed the learning more deeply that would otherwise have been the case. This is an on-going project and the first step was to ensure the assessment was done as per NICE guidelines. The early indicators are positive, however, the process needs to be monitored to ensure the change is sustained. There are further sections of the NICE guidance on this subject that can now be implemented. This includes the assessment of patients remotely assessed and the quality of advice given to patients, particularly those who have a risk of green or amber on the traffic light system. Given the exponentially increasing medical knowledge (Smith 1978) individualistic approaches to deliver reliable evidence based care cannot be sustainable or effective given the volume of new knowledge. Whilst the need for guidelines, hard Page | 15 work, vigilance and individualistic approached are necessary, a systems based multifacet approach incorporating the cultural of the organisation, the task, environment, the team, the individual and the patient, provides the potential to translate evidence into practice reliably. There has been much debate and discussion of whether quality improvement approaches are effective and the evidence answering that question is limited (Boaden et al. 2008). In the absence of evidence it is important improvements are made and it has been suggested that organisation will gain more from identifying and utilising an approach to quality improvement (Walshe 2002). Page | 16 Page | 17 Appendices Appendix 1 – Project Plan Page | 18 Paresh Dawda Appendix 2 - The practice as a system Page | 19 Paresh Dawda Appendix 3 – Driver Diagram for Patient Care Process Page | 20 Paresh Dawda Appendix 4 – Process Map Page | 21 Page | 22 Appendix 5 – Sustainability Analysis Your score Your total score for this review period is: 63.2 Preliminary evidence suggests a score of 55 or higher offers reason for optimism. Scores lower than 55 suggest that you need to take some action to increase the likelihood that your improvement initiative will be sustainable. Page | 23 Paresh Dawda Appendix 6 – Results of Surveys Which statement applies best to your awareness of this guidance? Relevance: How relevant do you think the following measures are in the assessment of febrile children and how often do you measure them ? Measure: Page | 24 How often do you not measure the temperature because you cannot find a working thermometer to hand ? Do you know where to find an electronic axillary thermometer in the surgery ? What is your level of confidence in interpreting the values for temperature, pulse rate, respiratory rate and capillary refill time for different age groups of children ? Freetext comments Until i started to look at this as an improvement project i was no that Page | 25 aware of the guidance question 3 always have a thermometer. question 5 confident in interpretation when i have looked up the relevant values need easy prompt to fill in examination onto records please. Interested to find out how you are going to use the survey -great idea! Made me read the guidelines and ?change practice Re question 3 I always measure temperature as keep a thermometer as part of my personal equipment. This is not an option and cannot complete form unless tick a box so have ticked one but this is not the true answer. Would formally use traffic light system if a card / sheet in rooms making easier to refer to. I do need to review the guidance more regularly I generally need to look up values for pulse and resp rate in very young infants I find tympanic membrane thermometer unreliable at times - this may be due to uncooperative child, wax in ear, narrow canal. no always necessary to measure respiratory rate accurately if child appears well and breathing rate looks normal. sometimes do not measure temp if child seems well otherwise. Page | 26 Page | 27 Appendix 7 – Log of a selection of PDSA Cycles Date Plan Do Study Act What are we trying to accomplish? To develop a data collection strategy so data collection is quick and efficient How will we know that a change is an improvement? If the data collection can be done quickly and easily without taking too much time. Qualitative feedback. What change can we make that will result in improvement? Design a search strategy to identify the population of patients under the age of five with a fever 21.1.201 1 Design a spread sheet to collect data on children under the age of 5 who have presented with a view to establishing baseline measure of % of patient who have complied with NICE guidelines. I will collect data from those patients who were seen on one day. I will assess if the spread sheet and the operation I performed this task on 24 Jan. I did a search on patients under the age of five who presented on Friday 21st and reviewed their notes and completed the draft spread sheet On reviewing these patients I identified a group who had been assessed remotely and they therefore did not have the parameters on the spreadsheet completed. Of the 49 patients identified in my search strategy a large number had been seen for other reasons e.g. immunisations etc. This led to unnecessary time being wasted in reviewing their notes. I reviewed the operational definition and decided that I need to look at data for two populations those remotely assessed and those assessed face to face. For those remotely assessed I need to do a literature review exercise. I also reviewed the search strategy to group by clinics to minimise time spent on reviewing unnecessary case notes Page | 28 Paresh Dawda definition are workable. 29.1.201 1 I will redesign the search strategy to group by clinics and review case notes to ensure minimal amount of time wasted. I will also focus on the those seen by face to face consultation at this stage. I redesigned the search strategy. The patients are now grouped by session (GP Surgery, Minor illness, UAT AM and UAT PM) and I can select the relevant ones quickly This enabled me to identify the group of children to look at much quickly. I will use this search strategy What are we trying to accomplish? To ensure thermometers of both types are available in each consulting room How will we know that a change is an improvement? audit of equipment What change can we make that will result in improvement? Check stock and inventory, Identify stock and site, Try visual management (5S) Page | 29 13.5.201 1 There are occasions when absence of thermometer prevents the task from occurring. I will therefore test and try out a 5S type of approach to make place the thermometer in same place in different consulting rooms with a visual management system if it is not there. I will design the base for the visual management and show it to the HCA and ask them for feedback. Two type of layout created and HCA will action and apply to all rooms week commencing 31 May. A snapshot audit to be carried out 1-2 weeks after implementation of this. I designed this and showed it. There was some scepticism but HCA were happy to try out (Interestingly they saw how it could be applied to other aspects of room layout). We need two type of template one with BP monitor on outside and one on inside depending on the layout of the room. Figure 1: Impact of 5S Intervention Page | 30 Figure 2: 5S table top visual management card Figure 3: 5S visual management card + equipment What are we trying to accomplish? In ever consultation with feverish child all four parameters of assessment happen reliably How will we know that a change is an improvement? % of children with all four assessments completed, Subjective feedback What change can we make that will result in improvement? Memory prompt on thermometers Page | 31 31.5.2011 Measurement of temperature is occurring 80% of the time. I will therefore try a human factors intervention and see if by stick a label on the thermometer to remind to check PR/RR/CRT has any impact. I will do it at the surgery in the morning session with a member of the UAT team and see if that improved the recording of the 4 measure at the end of the morning I tried this with two people during a UAT morning clinic The qualitative feedback was this is helpful. They measured the items for the patients their saw that morning but they said recording it was a problem. I will use this solution and look at testing solutions to make recording of data easier. The solution was implemented during week of 31.5.2011 by HCA. Page | 32 Figure 4: Tympanic thermometer with memory prompt Figure 5: Digital thermometer with memory prompt What are we trying to accomplish? Trying to ensure once they make the measurements clinicians apply them and interpret them correctly. How will we know that a change is an improvement? Qualitative feedback & Hit rate % of children who have had all four measurements done having traffic light system assessment recorded (Green, Amber, Red) in the notes What change can we make that will result in improvement? Make the normal values and traffic light systems easily available for all clinicians, Normal values as a mouse mat. 12.5.201 1 The questionnaire suggested people do not always remember the normal values. I therefore will see if the normal values on a 4x6 card on the noticeboard is helpful I asked 2 members of the UAT to team to review this and feedback. They found I useful. They identified that there was scope for adding normal CRT time there as well. They also said that whilst helpful there is so much on notice boards I observed the task process and noted that the consistent item always visible is the Mouse Mat. The first batch was printed together with taking account of traffic light system but these were too small in print to be of use. Hence only normal values used and solution implemented 9 June 2011. Page | 33 What are we trying to accomplish? Trying to ensure once they make the measurements clinicians apply them and interpret them correctly. How will we know that a change is an improvement? Qualitative feedback & Hit rate % of children who have had all four measurements done having traffic light system assessment recorded (Green, Amber, Red) in the notes What change can we make that will result in improvement? Make the normal values and traffic light systems easily available for all clinicians, Normal values as a mouse mat 12.5.201 1 The questionnaire suggested that people also did not generally apply the traffic light system and there was one specific request for prompts. I will test out during one UAT clinic and ask Nurse/GP whether an A5 double sided prompt is helpful with traffic light system on one side and management on the other. I will ask the questions: 1) Does it make sense 2) Is there sufficient/too little or too much nfo 3. Is it helpful and any other comments I asked two member of the UAT team to test this out. One was a nurse and one a GP. The feedback was that this was helpful. It was suggested that the abnormal values could be in bold to highlight them more. It was also suggested that pieces of paper/prompts on noticeboards get mislaid/lost. I made visual changes to the prompts as advised. Instead of paper on noticeboard I thought about having an easily referenced page on the intranet. I also thought about placing it on a mouse mat but the print was too small. Hence only the normal values were placed on the mouse mat. Page | 34 Figure 6: Mouse mat Figure 7: Mouse mat enlarged Figure 8: Screenshot of intranet with traffic light system reference What are we trying to accomplish? Improve the recording of (and make it easier to interpret) the assessments How will we know that a change is an improvement? % of consultation with febrile children where template has been used. What change can we make that will result in improvement? Create a template for recording so data entry can be easily entered (and coded) Page | 35 14.5.201 1 The questionnaire suggests that there is belief in the value of the measurements in general and the statement is people say they measure it more than what is actually recorded. Is this therefore a recording issue? I will devise a recording template to try and make it easier to record. I created a recording template with the following Read code structure: Template Title temperature symptoms (165) Temperature: 2E3 Pulse Rate: 242 Respiratory Rate: 235 CRT: 24J0 (abbreviated to CRT) The template was linked to the read code temperature symptoms and also inserted as a sub template in the Acute Respiratory Infections template. The template was programmed so this information was only requested if the patient was less than 5 years of age. The template was tested. I looked at the one days use of the template. I learnt that people use a whole range and variety of read codes so the template may not be called up every time. Also the entire template is voluntary and there is no forcing function. However, if the will is there it does make it easier to read code Another solution (redundancy) required to help with this. The template worth maintaining and may be able to build on e.g. add the outcome of traffic light assessment. Page | 36 Figure 9: Screenshot of data recording template What are we trying to accomplish? Trying to make sure that there is a redundancy check in the process to make capture where the assessment has not taken place How will we know that a change is an improvement? % of occasions when redundancy check implemented What change can we make that will result in improvement? Create and electronic “Protocols” such that when the electronic record is saved it checks to make sure assessments have been recorded (& prompts) Page | 37 29.5.201 1 Hypothesis: Redundancy check could be done using an electronic protocol. The protocol was designed (see chart) and tested on a test patient. The Read Code acute respiratory infection was linked to the protocol. I will review the next day’s data to see what percentage of people who use the problem title for consultation on that day in children complete the template. An FMEA was also conducted on this redundancy check (Appendix 8 – FMEA) This is an automated protocol which will be performed on 31.5.2011 and I will review the results at the end of the day. No patients with acute respiratory infection problem title seen today Reassess tomorrow. Add cough as another problem title. This became and iterative process as so many different codes being used so data collection expanded to review read code usage, and each time a new code was used it was linked to the protocol. 1.6.2011 - five further triggers added to redundancy protocol Page | 38 Figure 10: Diagram of algorithm for redundancy check with screen shot of prompt Page | 39 Appendix 8 – FMEA Step 1 2 Failure Mode Triggers Protocol performing Causes Consequence Liklihood (1-5) Risk Liklihood * Consequ ence Consequ ency (1-5) Mitigation Read code not linked to algorithm redundacy process fails 4 x 2 = 8 review read codes used in daily search and proactively link with electronic protocol Clincian does not use a read code at all redundacy process fails 2 x 2 = 4 design postcard to provide individual feedback Clinician escapes from the protocol redundacy process fails 3 x 2 = 6 designed a step into protocol to advice clinician that they areviolating NICE guidance Clinican free texts data redundacy process unnecessarily activated 3 x 2 = 6 data entry template will minimise this occuring. Consider activating template based on read codes also x = x = x = x = x = x = x = Page | 40 Appendix 9 – Measurement Figure 12: : Pareto analysis - baseline data Figure 11: Run chart of % of febrile children with all four components completed Start of PDSAs Implementation of Redundancy Read code human factors PDSA check not linked Locum Figure 13: Number of measurements for each patient Change introduced Figure 14: Balancing measure Page | 41 Paresh Dawda Page | 42 Paresh Dawda References Amalberti, R. et al., 2006. Violations and migrations in health care: a framework for understanding and management. Qual Saf Health Care, 15 Suppl 1, pp.i66-71. Amnis, 2011. Safe and Effective Service Improvement: Delivering the safety and productivity agenda in healthcare using a Lean approach. , 43(1). Anon, 2009. How do I create a distinctive performance culture ?, McKinsey & Company. Baker, R., 2000. Managing quality in primary health care: the need for valid information about performance. Qual Health Care, 9(2), p.83. Available at: 2 - baker - managing quality qhc.pdf. Beckman, H.B. & Frankel, R.M., 1984. The effect of physician behavior on the collection of data. Annals of Internal Medicine, 101(5), pp.692-696. Boaden, R. et al., 2008. Quality improvement : theory and practice in healthcare, Coventry: NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. Clarke, J., Davidge, M. & Lou, J., 2010. The how to guide for measurement for improvement, Harnden, A. et al., 2009. Child deaths: confidential enquiry into the role and quality of UK primary care. The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 59(568), pp.819-24. Hawkins, J. & Lindsay, E., 2006. We listen but do we hear? The importance of patient stories. British journal of community nursing, 11(9), pp.S6-14. HSE, Reducing Error and Influencing Behaviour (Guidance Booklets), HSE Books. IHI, 2007. Designing Reliability into Healthcare Processes. , (January), pp.1-9. Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2004. Patient Safety Leadership WalkRounds. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/NR/rdonlyres/53C62FFD-CC4A-4DEA-A86983B575DCEED8/640/WalkRounds1.pdf. Langley, G. et al., 2009. The improvement guide : a practical approach to enhancing organizational performance 2nd ed., San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Maher, L., Gustafson, D. & Evans, A., 2010. Sustainability Model and Guide. McGlynn, E.A. et al., 2003. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. The New England journal of medicine, 348(26), pp.2635-45. Page | 43 Paresh Dawda Michie, S. & Johnston, M., 2004. Changing clinical behaviour by making guidelines specific. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 328(7435), pp.343-5. Available at: NICE, 2007. Feverish illness in children under 5 years assessment and initial management in children younger than 5 - Guidelines. , 93(CG47). Pink, D.H., 2009. Drive: The Surprising Truth about What Motivates Us, Canongate Books. Pronovost, P.J., Berenholtz, S.M. & Needham, D.M., 2008. Translating evidence into practice: a model for large scale knowledge translation. BMJ, 337(oct06 1), p.a1714a1714. Reason, J., 2000. Human error: models and management. BMJ, 320(7237), pp.768-770. Available at: http://www.bmj.com/cgi/doi/10.1136/bmj.320.7237.768 [Accessed November 13, 2010]. Reason, J.T., 1990. The nature of error. In Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available at: Human error - 1 - The nature of error.doc. Reinertsen, J.L. & Johnson, K.M., 2010. Rounding to influence: Leadership method helps executives answer the “hows” in patient safety initiatives. Healthcare Executive, 25(5), pp.72-75. Resar, R.K., 2006. Making noncatastrophic health care processes reliable: Learning to walk before running in creating high-reliability organizations. Health services research, 41(4 Pt 2), pp.1677-89. Available at: Smith, E.P., 1978. Measuring professional obsolescence: a half-life model for the physician. Academy of management review. Academy of Management, 3(4), pp.914-7. Thompson, M.J. et al., 2006. Clinical recognition of meningococcal disease in children and adolescents. Lancet, 367(9508), pp.397-403. Thompson, M. et al., 2008. Using vital signs to assess children with acute infections: a survey of current practice. The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 58(549), pp.236-41. Van den Bruel, A. et al., 2007. Signs and symptoms for diagnosis of serious infections in children: a prospective study in primary care. The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 57(540), pp.538-46. Vincent, Charles, Taylor-Adams, S. & Stanhope, N., 1998. Framework for analysing risk and safety in clinical medicine. BMJ, 316(7138), pp.1154-1157. Walshe, K., 2002. Effectiveness of quality improvement: learning from evaluations. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 11(1), pp.85-87. Wilcock, P.M. et al., 2003. Using patient stories to inspire quality improvement within the NHS Modernization Agency collaborative programmes. Journal of clinical nursing, 12(3), pp.422-30. Page | 44