ADVANCE DIRECTIVEs in Australia Overview

advertisement

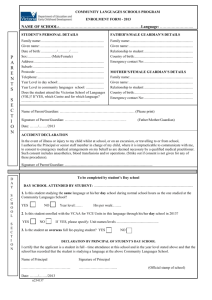

ADVANCE CARE PLANNING LEGISLATION – AUSTRALIA* State/ Territory Advance Directive/ Refusal of Treatment Yes Proxy/ Agent: Patient Appointed Yes Queensland Yes Yes South Australia Yes Yes New South Wales Comments Persons can appoint an Enduring Guardian or substitute decisionmaker (Guardianship Act of 1987 amended in 1997) and are able to record their treatment choices in an Advance Care Directive. An Advance Care Directive that complies with the requirements set out in the guidelines published by the Department of Health (NSW) is legally binding in NSW, and functions as an extension of the common law right to determine one’s own medical treatment (http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/policies/). Where no Enduring Guardian was appointed a Person Responsible is asked to make decisions on their behalf. The Person Responsible can be, in hierarchical order: (1) a guardian who has the function of giving consent to medical decisions; (2) a spouse or de facto spouse with a close and continuing relationship; (3) an unpaid carer (not counting a carer’s pension), or the patient’s carer before they were taken into residential care/supported accommodation; or (4) a close friend or relative) Powers of Attorney Act 1998 (Qld) passed by Parliament May 1998 and the Guardianship and Administration Act passed in May 2000 allow persons to draft Advance Health Directives and sign an Enduring Power of Attorney for personal/health matters to assign an Attorney (substitute decision maker). Where not enduring power or attorney was signed regarding health matters, a Statutory Health Attorney is automatically assigned to make such decisions. The Statutory Health Attorney, in order of priority, can be a spouse, primary unpaid carer, family member or close friend, or the Adult Guardian (as a last resort). An Adult Guardian or guardian of last resort can be appointed by the Guardianship and Administration Tribunal. This guardian can consent to withhold/withdraw life-sustaining treatment. In South Australia the Consent to Medical Treatment and Palliative Care Act as well as the Guardianship and Administration Act allow for the following legal instruments, together referred to as advance directives: Medical Powers of Attorney, Anticipatory Directions and Enduring Powers of Guardianship. Persons can state their refusal of or consent to treatment in anticipation of a terminal illness or a permanent vegetative state verbally or document it in their Medical Power of Attorney or Anticipatory Direction. Individuals may specify a person who they would wish to make health decisions for them if they become unable to make those decisions personally or communicate them by signing a Medical Power of Attorney. That person is known as a MPA or Medical Agent. The Medical Agent can make decisions about medical treatment, including withdrawing or withholding life-sustaining measures, but not refusal of the natural provision/administration of food and water, or pain -relieving drugs. More than one Medical Agent can be nominated. Also, the Guardianship and Administration Act allows for the appointment an Enduring Guardian to make important health and lifestyle decisions in case the patient is legally considered unable to do so. An Enduring Guardian can potentially make a wider range of decisions than a Medical Agent. Some residents in aged care facilities are not competent and have not previously organised an advance directive. To assist staff in nursing 1 Tasmania No Yes Victoria Yes Yes Western Australia No Yes homes to know if a resident should be actively or passively treated, the Department of Health has endorsed the use of Good Palliative Care Plans for people in the terminal stage of terminal illness. Although not a legal document, it is a record of a discussion between the patient, family and the doctor about palliative care or active treatment. The Good Palliative Care Plan is written by a doctor in consultation with legally appointed agents and/or family members. Where no Medical Agent or Enduring Guardian has been appointed, a relative may consent to certain medical treatment. Moreover, the Guardianship Board may appoint a Guardian to make lifestyle and medical treatment decisions for a person with a mental incapacity. The Guardian could be a family member or close friend. If there is nobody suitable to become guardian, the Office of the Public Advocate may be appointed as guardian of last resort. The Guardianship and Administration Act of 1995 allows persons of or over the age of 18 to appoint an Enduring Guardian. The appointee must act in accordance with the treatment choices of a person where recorded, the principles laid down in the act, as well as in a number of important respects is subject to direction by the Board. Where no Enduring Guardian has been appointed, a Person Responsible may be called upon to consent to medical decisions. A Person Responsible can be - a Guardian (including Enduring Guardian), who has the power to make decisions about heath care; or if there is no guardian - his or her spouse (this includes de facto spouses and same sex spouses); or if there is no spouse - an unpaid carer who is now providing support to the person or provided this support before the person entered residential care; or if there is no carer - a close relative or friend of the person, who has a close personal relationship with the other person through frequent personal contact and who has a personal interest in the other person’s welfare. In case the above means of decision-making fail, the Guardianship and Administration board has the power to appoint a Guardian as a ‘last resort’ option. Medical Treatment Act 1988 (Vic) allows a patient to write a Refusal of Treatment Certificate, but only for a current illness which does not have to be terminal (ie not anticipatory). The Medical Treatment (Enduring Power of Attorney) Act 1988 (Vic) allows the appointment of an Agent (proxy) as well as an Alternate Agent. Where no Agent has been appointed a Person Responsible will be determined to make decisions on behalf of the incompetent patient. A Guardian can be appointed by the Guardianship List of the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (the Tribunal) as a measure of ‘last resort’. No current legislation exists regarding advance care planning. A Private Members Bill for the refusal of treatment by terminally ill people (Medical Care of the Dying Bill 1995 (WA)) was passed by the Lower House November 1995 but lapsed when an election was called. More recently, a discussion paper issued by the Attorney General in 2005 stated that the common law would be highly likely to support the view that a competent person has the right to “give binding consents and refusals regarding the manner of his or her own future health care”. The paper’s view was that a validly executed advance directive would be legally binding. There is legislative provision with respect to substitute decision makers in WA. The Guardianship and Administration Act (1990) provides for appointment of a Guardian for those who are incapable. Guardians are authorised to make decisions of a personal nature 2 Australian Capital Territory Yes Yes Northern Territory Yes No including consent for medical treatment including the withdrawal of treatment. In addition, in the context of the Act, a guardian can effect the non-provision of certain treatment that may be available including non-natural hydration and nutrition. The latter point was made by the Guardianship and Administration Board in Re BTO (Application GU 0192/2004). In the event that an individual is not capable, needs medical treatment and does not have a guardian, section 119 of the Act allows for consent to be given by a Person Responsible. Under the Powers of Attorney Act 1956, the Guardianship and Management of Property Act 1991, and the Medical Treatment Act 1994 persons can state their wishes regarding medical treatment (advance directives) and appoint a substitute decision maker to refuse medical treatment when the appointer is no longer competent. If possible, the previously stated wishes of a person, prior to them becoming incompetent, are to be considered when substitute decision makers are making medical treatment decisions on behalf of an individual. The previously stated wishes, whether they are in writing or verbal, provide evidence to assist in medical treatment decisionmaking. And although the written wishes may not appear in a signed legal document, under statute law they have evidentiary weight under common law and are considered in the Powers of Attorney Act 1956 and the Guardianship and Management of Property Act 1991. The Powers of Attorney Act (1956) allows a person (Donor) to appoint a Donee (substitute decision maker) by completing an Enduring Power of Attorney. This allows the Donee to give consent when the person becomes incapacitated to medical treatment which is necessary for their well being, the donation of a body part, blood or tissue and the withholding or withdrawal of medical treatment. The Guardianship and Management of Property Act 1991 establishes a Tribunal which has powers to appoint a Guardian as a measure of ‘last resort’ where the health of an incompetent person is endangered. Natural Death Act 1988 (NT) allows a person 18 years or over to write an Advance Directive at any time, but it applies only to a terminal illness. It may be that the legislation could allow for an application of the Enduring Power of Attorney to medical decisionmaking. However, for medical decisions the Enduring Power of Attorney has currently no recognition under statute law in the NT. It is important to keep in mind that the appointment of such a person could potentially be challenged in a court of law if other parties felt uncomfortable with the process or decisions being made. Because a guardian appointed under the Adult Guardianship Act has limited decision-making power, decisions regarding the cessation of medical treatments in an end-of-life situation should be referred to the Magistrate’s Court. * As per 4 December 2006. All States and Territories have guardianship legislation. This table is based on a schedule introduced by Margaret Brown [1]. 1. Brown, M., The law and practice associated with advance directives in Canada and Australia: similarities, differences and debates. [Review] [73 refs]. Journal of Law & Medicine., 2003. 11(1): p. 59-76. 3 4