Chinese Sub-ethnic Identity in Nationalist

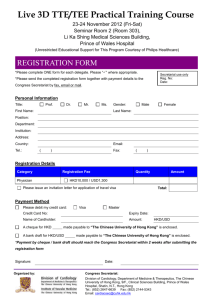

advertisement