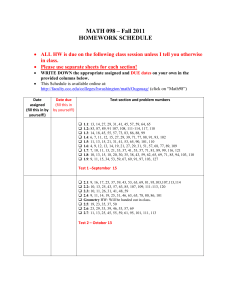

Chapter 2

advertisement

Math 3379

Chapter 2 - Venema

Homework 2

Chapter 2

2.4

Problem 10

Problem 12

08 points

12 points

2.5

Problem 04

Problem 05

Problem 08

Problem 10

08 points

08 points

06 points

08 points

2.6

Problem 01

Problem 02

Problem 03

10 points

10 points

10 points

1

Chapter 2 Axiomatic Systems and Incidence Geometries

In more recent times, and after lots of work on the foundations of mathematics, we

use an axiomatic structure for many topics.

Axiomatic structure

Undefined terms

A starting point - usually few, less than 10

Axioms

consideration.

Statements that are true for the system under

Called Postulates by Euclid.

Independent – an independent axiom cannot be

proved OR disproved as a logical consequence of

the other axioms.

Consistent – no logical contradiction can be

derived from the axioms

Definitions

Technical terms defined by various manipulations

of the undefined terms and axioms or from notions

introduced by proofs.

Theorems

Statements about relationships in the system that

have been proved. Called propositions by Euclid.

Interpretations

and Models

A way to give meaning to the system, often visual,

models are often helpful. A system may have

more than one model. A system with exactly one

model, with all other models being isomorphic to

one another is called categorical.

2

Geometry #1 – A Five Point Geometry

not from the book

Undefined terms: point, line, contains

Axioms

1. There exist five points

2. Each line is a subset of those five points.

3. There exist at least two lines

4. Each line contains at least two points.

Let’s come up with at least 2 non-isomorphic models for this system.

3

Geometry #2 A Flexible Geometry **

not from the book

Undefined terms:

point, line, on

Axioms:

A1

Every point is on exactly two distinct lines.

A2

Every line is on exactly three distinct points.

Models:

There are lots of very different models for this geometry.

Here are two:

One has a finite number of points and the other has an infinite number of points,

so they are non-isomorphs.

Model 1: 3 points, 2 lines

Points are dots and lines are S-curves. One line

is dotted so you can tell it from the second line.

Nobody ever said “lines” have to be straight things, you know.

Note, too, that there are only 3 points so my lines are composed of some material

that is NOT points, it’s “line stuff”. Some non-point stuff.

Luckily they’re undefined terms so I don’t have to go into it.

4

Model 2: an infinite number of points and lines

This is an infinite lattice. Each line is has 3 points along

it. It continues forever left and right

Your Model:

Put it in the CW Chapter 2 #1 Turn in Page once you’ve got it figured out.

Ideas for Definitions:

Biangle – each two-sided, double angled half of the first model…like a triangle but

only two points. Do biangles exist in Euclidean geometry (ah, no…check the

axioms…two lines meet in exactly ONE point in Euclidean geometry.)

Quadrangle – each diamond-shaped piece of the second model

5

Parallel lines – Parallel lines share no points. See the CW questions!

The second model has them; the first doesn’t. How many lines are parallel to a

given line through a given point NOT on that line in the second model? (two!

This, too, is really different than Euclidean Geometry).

Collinear points – points that are on the same line.

Midpoints – are these different from endpoints in a way that you can explicate in a

sentence for Model 2? Does it make sense to have a “distance”

function in

this geometry – maybe not…maybe this is something we’ll just

leave

alone.

What do you notice that cries out for a definition in your model? Again, the CW.

Theorems: Consider the following questions and formulate some proposed

theorems

(called “conjectures” until they’re proved

Flexible Geometry Exercise:

Are there a minimum number of points?

Is there a relationship between the number of points and the number of lines?

Why is this a Non-Euclidean Geometry? **TURN IN CW Chapter 2 #1 right now.

**This geometry is introduced in Example 1, page 30 of

The Geometric Viewpoint: a Survey of Geometries by Thomas Q. Sibley;

1998; Addison-Wesley (ISBN 0-201-87450-4)

6

INCIDENCE GEOMETRIES

Undefined terms:

page 16, Section 2.2

point, line, on

Axioms:

IA1

For every pair of distinct points P and Q, there exists exactly one line l such

that both P and Q lie on that line.

Note that the axiom uses all 3 undefined terms and is defining a relationship

among them.

IA2

For every line l there exist at least 2 distinct points P and Q such that both P

and Q lie on the line l.

IA3

There exist three points that do not all lie on any one line.

Definitions:

Collinear:

Three points, A, B, and C, are said to be collinear if there exists one

line l such that all three of the points lie on that line.

Parallel:

Lines that share no points are said to be parallel.

7

Interpretations and models:

(Note: non-categorical!)

The Three-point Geometry

Label the points A, B, and C

Check the axioms.

What is exactly 1/3 of the way between B and C? In other

words, what are lines made of ?

Alternate, and isomorphic models:

Theorem 1: Each pair of distinct lines is on exactly one point.

Proof of Theorem 1

Suppose there’s a pair of lines on more than one point. This cannot be because

then the two lines have at least two distinct points on each of them and Axiom 1

states that “two distinct points are on exactly one line”.

Thus our supposition cannot be and the theorem is true. QED

8

Theorem 2: There are exactly 3 distinct lines in this geometry.

Take a minute now and prove Theorem 2. You may work in groups or

individually. Turn in your proof in CW #2. Turn it in when I call time.

Last but not least:

How many parallel lines are there?

Could this be called non-Euclidean? Why?

9

The Four-point geometry

Undefined terms:

point, line, on

Axioms:

IA1

For every pair of distinct points P and Q, there exists exactly one line l such

that both P and Q lie on that line.

Note that the axiom uses all 3 undefined terms and is defining a relationship

among them.

IA2

For every line l there exist at least 2 distinct points P and Q such that both P

and Q lie on the line l.

IA3

There exist three points that do not all lie on any one line.

Same axioms!

Model:

Note the “at least 2” in IA2!

A planar shape, a tetrahedron, or octant 1 in 3-space

C

B

A

D

10

What are some alternate views on this model?

List the points:

Interpret point to be the symbol. Or for the octant, use the usual Cartesian idea.

List the lines:

{A, B},

Interpret line to be a set of 2 symbols. Or for the octant, use the usual Cartesian

idea.

In the planar shape, what is in between A and B?

How many parallel lines are there? Expand from “lines that share no points” to the

Playfair statement: Given a line and a point not on that line, how many lines go

through the point and share no points with the given line.

11

Why is this a geometry?

Why is this a non-Euclidean Geometry?

12

The Five -point Geometry

Undefined terms:

not from the book

point, line, on

Axioms:

IA1

For every pair of distinct points P and Q, there exists exactly one line l such

that both P and Q lie on that line.

Note that the axiom uses all 3 undefined terms and is defining a relationship

among them.

IA2

For every line l there exist at least 2 distinct points P and Q such that both P

and Q lie on the line l.

IA3

There exist three points that do not all lie on any one line.

Definitions:

Collinear:

Three points, A, B, and C, are said to be collinear if there exists one

line l such that all three of the points lie on that line.

Parallel:

Lines that share no points are said to be parallel.

13

Model:

P1

Points: {P1, P2, P3, P4, P5}

P2

P5

Lines: {P1P2, P1P3, P1P4, P1P5, P2P3, P2P4, P2P5,

P3

P4

P3P4, P3P5, P4P5}

Note that the lines crossover one another in the interior of the “polygon” but DO

NOT intersect at points. There are only 5 points!

Possible Definitions

Triangle -- a closed figure formed by 3 lines. An example: P2P1P4 is a triangle.

How many triangles are there?

Quadrilateral – a closed figure formed by 4 lines. An example: P2P5P4P3 is a

quadrilateral. How many quadrilaterals are there?

14

P1

P2

P5

P3

P4

Note that line P1P2 is parallel to line P4P5. So are P3P4 and P2P5…List them

ALL!

15

Five-point geometry Theorem 1:

Each point is on exactly 4 lines.

Let’s prove this right now – get in groups and get to work! First one done, get it

up on the board and we’ll tweak it together.

16

Another non-Euclidean!

The Seven-point geometry

page 18

Also known as Fano’s geometry.

(Gino Fano, published 1892)

A

F

B

G

C

D

E

{BDF} is a line! Nobody said “straight” in the axioms!

Where does {BDF} intersect {CBA}?

7 points and 7 lines…what’s the situation with respect to parallel lines?

17

Alternate axioms for Fano’s Geometry:

Axioms for Fano's Geometry

Undefined Terms. point, line, and incident.

Axiom 1. There exists at least one line.

Axiom 2. Every line has exactly three points incident to it.

Axiom 3. Not all points are incident to the same line.

Axiom 4. There is exactly one line incident with any two distinct points.

Axiom 5. There is at least one point incident with any two distinct lines.

A

F

B

G

C

D

E

Sometimes MORE THAN ONE list of axioms generates the SAME Geometry.

18

There are exactly 7 points in Fano’s Geometry. Count them in the model to make

sure. Now let’s get busy on CW Chapter 2 #3. Proving this, given 7 points,

exactly 7 lines…

Turn it in when I call time.

Enough with finite geometries – there’s an infinite number of them!

In fact, let’s talk about how many there are:

Is there a geometry with 17 points? 1927 points (why did I pick that number?)

N points?

19

A detour to a big well-known geometry:

Sphererical Geometry

The unit sphere is NOT a model for an incidence geometry but is very important in

the development of an understanding of modern geometry. We will spend a bit of

time on it.

Undefined terms:

point, line, on

Axioms:

IA1

For every pair of distinct points P and Q, there exists exactly one line l such

that both P and Q lie on that line.

The sphere fails to satisfy this axiom. WHY?

How can we change the axiom so it “works”?

IA2

For every line l there exist at least 2 distinct points P and Q such that both P

and Q lie on the line l.

True for the sphere.

IA3

There exist three points that do not all lie on any one line.

True for the sphere.

20

Interpretation and notation:

Point: an ordered triple (x, y, z) such that it satisfys x2 y 2 z 2 1 . In other words,

points are on the surface of the unit sphere.

Line: a great circle on the sphere’s surface. A Euclidean plane containing a great

circle includes the center of the sphere (0, 0, 0).

On:

is an element of a solution set

S2

will denote the unit sphere. It is embedded in 3 dimensional Euclidean

space.

Lines:

Between two points!

What are non-great circles and what makes them interesting?

What’s the situation vis a vis parallel lines in this model?

21

What is the minimal closed polygon in a sphere?

Let’s talk distance and angle measure

There are triangles, how do they compare to Euclidean triangles. Measure and sum

in small groups.

22

CW Chapter 2 #4

Comparing SG and EG, what’s the same, what’s different?

Let’s take a few minutes in small groups to make some lists

What’s the same as Euclidean Geometry?

What’s different from Euclidean Geometry?

Now fill out CW Chapter 2 #4 and turn it in.

23

Let’s look at the Cartesian plane:

Undefined terms:

page 19

point, line, on

Axioms:

IA1

For every pair of distinct points P and Q, there exists exactly one line l such

that both P and Q lie on that line.

Note that the axiom uses all 3 undefined terms and is defining a relationship

among them.

IA2

For every line l there exist at least 2 distinct points P and Q such that both P

and Q lie on the line l.

IA3

There exist three points that do not all lie on any one line.

Interpretation and notation:

Point: any ordered pair (x, y)

Line: the collection of points whose coordinates satisfy a linear equation of the

form y = mx + b

On: A point is said to lie on a line if it’s coordinates satisfy the equation of that

line.

R2

will symbolize the Cartesian plane

Why is THIS symbol used?

First let’s use the definition of cross product from Modern Algebra…who knows

it?

24

Why is this called the Cartesian plane and not just THE plane?

Argand Plane, among others

25

The Klein disk

page 20

Points will be {(x, y) x2 + y2 < 1}, the interior of the Unit Circle, and lines will be

the set of all lines that intersect the interior of this circle. “on” has the usual

Euclidean sense.

So our model is a proper subset of the Euclidean Plane.

Model:

Note that the labeled points (except H) are

NOT points in the geometry. A is on the

circle not an interior point. It is

convenient to use it, though.

A

B

H

P1

P2

C

D

G

F

E

H is a point in the circle’s interior and IS

a point in the geometry.

We cannot list the number of lines – there are an infinite number of them.

Is everybody clear on what is and is not in our space?

26

Checking the axioms:

Undefined terms:

point, line, on

Axioms:

IA1

For every pair of distinct points P and Q, there exists exactly one line l such

that both P and Q lie on that line.

Inheriting…

IA2

For every line l there exist at least 2 distinct points P and Q such that both P

and Q lie on the line l.

Inheriting…

IA3

There exist three points that do not all lie on any one line.

Inheriting…

Definitions:

Collinear:

Three points, A, B, and C, are said to be collinear if there exists one

line l such that all three of the points lie on that line.

Parallel:

Lines that share no points are said to be parallel.

27

In Euclidean Geometry, there is exactly one line through a given point not on a

given line that is parallel to the given line. Interestingly, in this geometry there are

more than two lines through a given point that are parallel to a given line.

A

B

H

P1

P2

C

D

G

F

Let’s look at lines GC and GB. They

intersect at G…which is NOT a point in

the geometry. So GC and GB are parallel.

In fact, they are what is called

asymptotically parallel. They really do

share no points.

E

Now look at P1P2. It, too, is parallel to GC. Furthermore both P1P2 and GB pass

through point H. P1P2 is divergently parallel to GC.

Not only is the situation vis a vis parallel lines different, we even have flavors of

parallel:

asymptotic and divergent. So we are truly non-euclidean here, folks.

28

Theorem 1: If two distinct lines intersect, then the intersection is exactly one

point.

Inherited from Euclidean Geometry.

Theorem 2: Each point is on at least two lines.

Each point is on an infinite number of lines.

Theorem 3: There is a triple of lines that do not share a common point.

FE, GC, and AD for example.

Now for the usual:

CW Chapter 2 #5 Compare and contrast the Klein Disc to Spherical Geometry

Visit in groups and then we’ll turn in #5.

29

2.3

The Parallel Postulates in Incidence geometry

page 20

Definition:

Parallel lines:

Lines that are parallel do not intersect. i.e. they share no

points.

This works in 2D and we’ll be in 2D for this course, except for Spherical

Geometry. Now, in contrast to some high school geometry books: a

line cannot be parallel to itself in our course.

See the Official Definition, bottom of page 20

Definition 2.3.1

We find that there are several ways for a geometry to be configured with respect to

parallel lines.

One way is to have none, one way is the Euclidean way exactly one, and there’s a

third possibility, too, exemplified with the Klein Disc – more than

one.

Euclidean Parallel Postulate:

For every line l and for every point P that does not lie on l, there is exactly one line

m such that P lies on m and m is parallel to l.

Illustration

30

Which Incidence geometry models have this property?

Three-point geometry

Four-point geometry

Five-point geometry

Fano’s geometry

Klein disk

Spherical geometry

Elliptic Parallel Postulate

For every line l and for every point P that does not lie on l, there is no line m such

that P lies on m and m is parallel to l.

What about the Sphere? None. Which have we looked at that don’t have any

parallel line

Which Incidence geometry models have this property?

Three-point geometry

Four-point geometry

Five-point geometry

Fano’s geometry

Cartesian plane

Klein disk

Spherical geometry

31

Hyperbolic Parallel Postulate

For every line l and for every point P that does not lie on l, there are at least two

lines m and n such that P lies on m and n and both m and n are

parallel to l.

Which Incidence geometry models have this property?

Three-point geometry

Four-point geometry

Five-point geometry

Fano’s geometry

Cartesian plane

Klein disk

Spherical geometry

32

Independence of the Axiom concerning Parallelism:

We have just looked at an axiomatic system for Incidence geometries:

Undefined terms:

point, line, on

Axioms:

IA1

For every pair of distinct points P and Q, there exists exactly one line l such

that both P and Q lie on that line.

Note that the axiom uses all 3 undefined terms and is defining a relationship

among them.

IA2

For every line l there exist at least 2 distinct points P and Q such that both P

and Q lie on the line l.

IA3

There exist three points that do not all lie on any one line.

Definitions:

Collinear:

Three points, A, B, and C, are said to be collinear if there exists one

line l such that all three of the points lie on that line.

Parallel:

Lines that share no points are said to be parallel.

We have seen that all 3 of the incidence axioms are satisfied by a plethora of

models. Thus adding IA4, an axiom about parallelism will cause our outlines of

axiomatic systems to have subcategories. Because there are models of the first 3

axioms that have different situations with respect to parallel lines, we know that an

axiom about parallelism is INDEPENDENT from the first 3 axioms. It cannot be

logically derived from them.

33

Please read section 2.4 Axiomatic Systems and the Real World with an eye toward

your term paper. There are some valuable thoughts there.

34

Hyperbolic Geometry, an introduction

Similar to the Klein Disk, Hyperbolic geometry is in the unit circle with the circle

itself NOT in the space. The lines, however, are orthogonal circles.

35

Historical Background of Non-Euclidean Geometry

About 575 B.C. Pythagoras wrote his book on Geometry. Some of the material

was known in other cultures centuries before he wrote it down, of course. His was

the first axiomatic approach to organizing the material. Interestingly, he did as

much work as he could before introducing the Parallel Postulate. Many people

have interpreted this progression in his work as indicating a level of discomfort

with the Parallel Postulate. It’s not really possible to know what he was really

thinking. About 400 years after the birth of Christ, Proclus, a Greek philosopher

and head of Plato’s Academy, wrote a “proof” that derived the Parallel Postulate

from the first 4 Postulates. thereby setting the tone for research in Geometry for the

next 1400 years. Johann Gauss, the great German mathematician, actually realized

that there was another choice of axiom but didn’t choose to publish his work for

fear of getting into the same trouble as other scholars had with the Catholic

Church.

Around 1830, two young mathematicians published works on Hyperbolic

Geometry – independently of one another. The world took no note of them. In

1868, the Italian Beltrami found the first model of Hyperbolic Geometry and in

1882, Henri Poincare developed the model we’ll study.

120 years later, Hyperbolic Geometry is finally making it into high school

textbooks. My favorite is a text that St. Pius X used in the 90’s. If you ever get a

chance to look at it – it’s just terrific. And it includes a section on Spherical

Geometry as well:

Geometry, second edition by Harold Jacobs. ISBN: 0-7167-1745-X (copyright

1987).

36

Note that St. Pius isn’t a flagship diocese school – they actually have a very full

section of “Algebra half”, the course for the kids not ready for Algebra I.

In the 1400 years of work on the axioms of Absolute Geometry there was always a

special group of people who endeavored to prove that the Parallel Postulate was

actually a theorem. In fact, Saccheri and Lambert who both came so close to

realizing that there was an alternate geometry out there waiting to be discovered

never got all the way past believing that the axiom was a theorem. Here is a list of

statements that are equivalent to P1, the Euclidean Parallel Postulate:

The area of a triangle can be made arbitrarily large.

The angle sum of all triangles is a constant.

The angle sum of any triangle is 180.

Rectangles exist.

A circle can be passed through any 3 noncollinear points.

Given an interior point of a angle, a line can be drawn through that point

intersecting both sides of the angle.

Two parallel lines are everywhere equidistant.

The perpendicular distance from one of two parallel lines to the other is

always bounded.

37

Hyperbolic Geometry Workbook

The Poincare model for Hyperbolic Geometry is the following:

Points are normal Euclidean points in the Cartesian Plane that are included in a

disc:

{(x, y) x 2 y2 r 2 }

[We usually pick r = 1.]

The points of the circle that encloses the disc are NOT points of Hyperbolic

Geometry nor are any points exterior to the circle.

Lines are arcs of orthogonal circles to the given circle. A circle that is orthogonal

to the given circle intersects it in two points and tangent lines to each circle at the

point of intersection are perpendicular. Note that diameters of the disc are lines in

this space even though they don’t look like arcs; each diameter is said to be an arc

of a circle with a center at infinity.

Here are two orthogonal circles in a Sketchpad graph. Draw in the tangent lines to

see this!

38

fx =

1-x2

1.4

gx = - 1-x2

5

hx =

8

5

qx = -

- x-

8

5

4

- x-

5

4

2

+

2

+

1

1.2

4

1

1

4

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

-2.5

-2

-1.5

-1

-0.5

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

-0.2

-0.4

-0.6

-0.8

-1

-1.2

-1.4

Enrichment 1:

Lines in our space:

Poincaré Disk Model

This sketch depicts the hyperbolic plane H2 usin g the Poincaré disk model. In this model, a line through

tw o poin ts is def ined as the Euclidean arc passing through the poin ts and perpendic ular to the circle.

Use this document's custom tools to perf orm constructions on the hyperbolic plane, comparing your f in dings

to equivale nt constructions on the Euclid ean plane.

Disk Controls

B

D

A

C

P. Disk Center

blue circle...not part of our space

39

Here is a sketch from Sketchpad that shows hyperbolic line H AB which is part of

the Euclidean circle intersecting the big blue circle (the given circle that is the

space boundary). Sketch in the tangent lines to the blue circle and H AB . Do you

see that the tangent lines are perpendicular?

Hyperbolic line CD is a diameter of the blue circle. It, too, is a line in our space.

Draw in the tangents and you’ll see why.

To find this space in Sketchpad: open the Sketchpad Program files, select

Samples/Sketches/Investigations/PoincareDisk. You have to use the sketching

tools under the double headed arrow down the vertical left menu to construct lines

and measure angles and such – you must not use the tools on the upper toolbar

(those are Euclidean tools). [You might have to start with My Computer/local

disk/Program files/Sketchpad, etc. – it depends on how the tech loaded Sketchpad

in the first place – it IS worth finding, though.]

40

Enrichment 2:

Parallel Lines in Hyperbolic Geometry

F

Disk Controls

B

G

A

D

E

H

H AB is parallel to every other line showing in the disc.

Since H AB intersects H DF on the circle, these two have a type of parallelism

called “asymptotically parallel”.

H DH and H DE are “divergently parallel” to H AB .

41

So we have H AB and a point not on it: Point D and we have 3 lines parallel to

H AB through D right there on the sketch. This illustrates our choice of parallel

axiom. And we now have two types of parallelism: asymptotic and divergent.

Do CourseWork Chapter 2 #6 right now and turn it in.

42

Enrichment 3:

Vertical angles are congruent.

F

Disk Controls

mGDI = 57.5

B

I put

poin

A

ts I

D

and

J

J on

E

H

with

mEDJ = 57.5

the

Eucl

idea

n

tool bar “points on arc” at the top of the page AND I measured these angles using

the Hyperbolic Angle Measure from the tool bar on the left under the doubleheaded arrow.

G

I

Are vertical angles congruent in Spherical geometry?

Euclidean Geometry?

The Klein Disk?

43

Enrichment 4:

Triangles and Exterior Angles

F

Disk Controls

L

mBAH = 35.3

B

mAHB = 40.5

mABH = 35.6

A

M

mLBM = 144.4

m1+m2+m3 = 111.44

m1+m2 = 75.80

H

Yes, we have triangles. No, the sum of the interior angles is not equal to 180; it is

LESS THAN 180 as promised. The difference between 180 and the sum of the

interior angles of a given Hyperbolic triangle is called the DEFECT of the triangle.

In Spherical geometry the difference between the sum of the interior angles of a

spherical triangle and 180 is called the EXCESS of the triangle.

And, as promised in the Exterior Angle Inequality Theorem, the exterior angle

(LBM in our example above) has a greater measure than either remote interior

angle. Thus this theorem is true in both Euclidean and Hyperbolic geometry.

In fact, its measure is greater than their sum (very non-Euclidean here – remember

ALL the facts after the Parallel Postulate in the Axioms section are Euclidean facts

and NOT applicable here in Hyperbolic Geometry). The Euclidean Exterior Angle

44

Equality Theorem (the exterior angle measures the sum of the 2 remote interiors) is

a Euclidean theorem not a Hyperbolic Theorem.

Note that the defect of the triangle is 58.6. (The sum of the angles is 121.4) We

Do CW #7 right now.

Now we’ve completed Chapter 2 with some extra material. Do the homework

after you read Chapter 2.

45