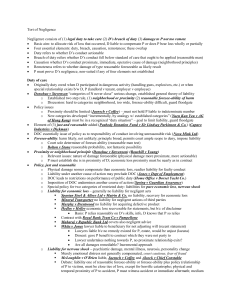

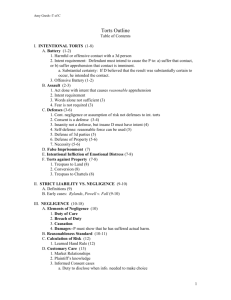

MichaelTORT - michaeldew.com

advertisement